An Aspect of Die-Production in the Middle Anglo-Saxon Period: the Use of Guidelines in the Cutting of Die-Faces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections Development Policy

Collections Development Policy Harris Museum & Art Gallery Preston City Council Date approved: December 2016 Review date: By June 2018 The Harris collections development policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, currently every 12-18 months while the Re-Imagining the Harris project develops. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the collections development policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of the Harris’ collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant policies/plans of the organisation: The Collections Development Policy should be read in the wider context of the Harris’ Documentation Policy and Documentation Plan, Collections Care and Conservation Policy, Access Policy Statement and the Harris Plan. 1.1. The Harris’ statement of purpose is: The Re-Imagining the Harris project builds on four key principles of creativity, democracy, animation and permeability to create an open, flexible and responsive cultural hub led by its communities and inspired by its collections. 1.2. Preston City Council will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3. By definition, the Harris has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. Preston City Council therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in the Harris’ collection. 1.4. Acquisitions outside the current stated policy will only be made in exceptional circumstances. 1.5. The Harris recognises its responsibility, when acquiring additions to its collections, to ensure that care of collections, documentation arrangements and use of collections will meet the requirements of the Museum Accreditation Standard. -

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

Viking: Rediscover the Legend

Highlights from Viking: Rediscover the Legend A British Museum and York Museums Trust Partnership Exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery 9 February to 8 September 2019 1.The Cuerdale Hoard Buried Circa 904AD Made up of more than 8,600 items including silver coins, English and Carolingian jewellery, hacksilver and ingots, the Cuerdale Hoard is one of the largest Viking hoards ever found. The bulk of the hoard is housed at the British Museum. It was discovered on 15 May 1840 on the southern bank of a bend of the River Ribble, in an area called Cuerdale near to Preston, in Lancashire. It is four times in size and weight than any other in the UK and second only to the Spillings Hoard found on Gotland, Sweden. The hoard is thought to have been buried between 903 and 910 AD, following the expulsion of Vikings from Dublin in 902. The area of discovery was a popular Viking route between the Irish Sea and York. Experts believe it was a war chest belonging to Irish Norse exiles intending to reoccupy Dublin from the Ribble Estuary. 2. The Vale of York Hoard Buried 927–928AD The Vale of York Viking Hoard is one of the most significant Viking discoveries ever made in Britain. The size and quality of the material in the hoard is remarkable, making it the most important find of its type in Britain for over 150 years. Comprising 617 coins and almost 70 pieces of jewellery, hack silver and ingots, all contained with a silver-gilt cup; it tells fascinating stories about life across the Viking world. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering -

A Viking Find from the Isle of Texel (Netherlands) and Its Implications Ijssennagger, Nelleke L

University of Groningen A Viking Find from the Isle of Texel (Netherlands) and its Implications IJssennagger, Nelleke L. Published in: Viking and Medieval Scandinavia DOI: 10.1484/J.VMS.5.109601 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2015 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): IJssennagger, N. L. (2015). A Viking Find from the Isle of Texel (Netherlands) and its Implications. Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 11, 127-142. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VMS.5.109601 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

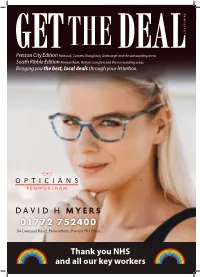

Thank You NHS and All Our Key Workers

GET THE DEAL ASHIRE C N A L Preston City Edition Fulwood, Cottam, Broughton, Grimsargh and the surrounding areas. South Ribble Edition Penwortham, Hutton, Longton and the surrounding areas. Bringing you the best, local deals through your letterbox. PENWORTHAM 01772 752400 34 Liverpool Road, Penwortham, Preston PR1 0DQ Thank you NHS and all our key workers GET THE DEAL • JULY 2020 | 1 WE WON’T BE BEATEN ON PRICE! FRESHEN UP OR UNWIND IN ONE OF MANY BATHROOM SUITES AVAILABLE TODAY FREE DESIGN SERVICE AVAILABLE Units 3 & 4, Preston Trade Park, Ribbleton Lane, Preston PR1 5AU T: 01772 651 500 PRESTON E: [email protected] www.howdens.com 2 | GET THE DEAL • JULY 2020 WE WON’T BE BEATEN ON PRICE! Contents Hello to everyone and welcome back to the July edition of Get the Deal Lancashire magazine. While we have all been adjusting to a new way of living it has given all of us a chance to FRESHEN UP OR UNWIND appreciate our surroundings. As we look forward to Summer hopefully IN ONE OF MANY BATHROOM SUITES we can re-connect with our AVAILABLE TODAY FREE local businesses who have DESIGN SERVICE been affected over the last AVAILABLE few months, we wish them all well. In this edition we have a feature from the Friends of Winckley Square and our regular recipes from Booths. We hope you enjoy this edition and we look forward Download our App. to our next edition in Search for “The Prestige” September. Best Wishes Michael Units 3 & 4, Preston Trade Park, Ribbleton Lane, Preston PR1 5AU 4 Priory Lane, Penwortham, Preston PR1 0AR Disclaimer T: 01772 651 500 www.theprestigebarbershop.co.uk All advertisiments are carefully checked when compiling Get-the-Deal Lancashire magazine. -

The Danes in Lancashire

Th e D a n es i n La nc as hi re a nd Yorks hi re N GTO N S . W . PARTI n ILLUSTRATED SHERRATT HUGHES n n : Soh o u a Lo do 3 3 Sq re, W. M a n chester : 34 Cros s Street I 909 P R E FACE . ‘ ’ ' THE s tory of th e childhood of our race who inh a bited th e counties of L a nca shire a n d Yorkshire before th e a t a n a m a a to th e Norm n Conques , is l ost bl nk p ge a a to-da a a popul r re der of y . The l st inv ders of our a a s h e a a n d shores , whom we design te t D nes Norsemen , not a n were the le st importa t of our a ncestors . The t t a a a t a n d u t H is ory of heir d ring dventures , cr f s c s oms , s a n d a a t th e t a belief ch r cter , wi h surviving r ces in our a a a n d a th e t t . l ngu ge l ws , form subjec of his book the a nd e From evidence of relics , of xisting customs a n d t a t t ac a n d a s r di ions , we r e their thought ction , their t a n d a a t a n d th e m firs steps in speech h ndicr f , develop ent e at o a of their religious conc ptions . -

The Lostock Hall Magazine the Lostock Hall

TheThe IssueIssue 1515 LostockLostock HallHall MagazineMagazine LostockLostock HouseHouse TrainspottingTrainspotting AroundAround LostockLostock HallHall AnAn ElephantElephant StoryStory F R E E Penwortham Supported & Printed by: ACADEMY Welcome to the 16th issue of The Lostock Hall Magazine, which also covers Tardy Gate and nearby parts of Farington. It is a collection of local history articles relating to the area. Many thanks to all our contributors and readers. Our thanks to Penwortham Priory Academy who support us by printing and formatting the magazine. Please support our local advertisers without them we could not produce our magazine. A copy of each issue will be kept in the Lancashire Records Office. Jackie Stuart has kindly allowed us to serialise her book entitled 'A Tardy Gate Girl'. Once again we have contributions from Tony Billington and Joan Langford. Additions to Thomas Moss CC photo in Issue 14, 3 names were omitted. Rest of front row after Tony Billington and Lennie Newell were David Barnish, Eddie Pye and Joe Johnson. Lostock Hall Spinning Company photo 2nd person on front row is Ivor Fish. It is Les Smith not Keith Smith. This year being the centenary of the First World War we are looking for any photos and memories of any soldiers who served in the Great War that you may like to share in the magazine. We are also collecting material for Preston Remembers and the South Ribble Remembrance Archive 1914-1918, which will include anything relating to World War One in our area. A photo, document, a memory, etc. Joan Langford's new book is now out entitled' Lest We Forget' which is the eighth book in the series 'Farington – a Lancashire Cotton Mill Village' – a series of books now much sought after. -

Cuerden Strategic Site Post Excavation Assessment Report

Post-excavation Assessment Cuerden Strategic Site, Cuerden Green, South Ribble, Lancashire Client: Lancashire County Council Technical Report: Oliver Cook, Ian Miller, Samatha Rowe Report No: SA/2018/53 Cuerden Strategic Site, Cuerden Green, South Ribble: Post-excavation Assessment Site Location: The site is bounded by Stanifield Lane (A5083) to the west, the A582 to the north, the M65 terminus and Wigan Road to the east, encompassing the hamlet at Cuerden Green in South Ribble, Lancashire NGR: Centred at SD 55526 24603 Internal Ref: SA/2018/53 Prepared for: Lancashire County Council Document Title: Post-Excavation Assessment: Cuerden Strategic Site, Cuerden Green, South Ribble, Lancashire Document Type: Archaeological Post-excavation Assessment Report Version: Version 1.2 Author: Oliver Cook Position: Supervisor Date: July 2018 Approved by: Ian Miller BA FSA Position: Assistant Director Date: October 2018 Signed: Copyright: Copyright for this document remains with the Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford. Contact: Salford Archaeology, Centre for Applied Archaeology, Peel Building, University of Salford, Salford, M5 4WT Telephone: 0161 295 4467 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: This document has been prepared by Salford Archaeology within the Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford, for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be used or relied upon for any other project without an independent check being undertaken to assess its suitability and the prior written consent and authority obtained from the Centre for Applied Archaeology. The University of Salford accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than those for which it was commissioned. -

Viking-Age Silver in North-West England: Hoards and Single Finds

10 Viking-Age Silver in North-West England: Hoards and Single Finds Jane Kershaw CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................149 Background: Wealth and Currency in North- West England before the Vikings .................................... 150 The ‘Age of Silver’ ................................................................................................................................ 150 The Uses and Meanings of Silver: The ‘Bullion’ and ‘Display’ Economies ......................................... 154 Economic Development ......................................................................................................................... 157 Reasons for Hoarding ............................................................................................................................ 158 Hoards vs Single Finds .......................................................................................................................... 159 Conclusions .............................................................................................................................................162 References ...............................................................................................................................................162 ABSTRACT Silver hoards of Scandinavian character are arguably the most important archaeologi- cal source for Viking activity in the North West. They give a clear impression -

Three Byzantine Coins Found Near the North Wirral Coast in Merseyside

THREE BYZANTINE COINS FOUND NEAR THE NORTH WIRRAL COAST IN MERSEYSIDE Robert A. Philpott The purpose of this note is to place on record three unusual finds of Byzantine coins from north Wirral which have been notified to Liverpool Museum in the last few years, and to evaluate their significance. DESCRIPTIONS 1.Justinian I (A.D. 527 65), bronze decanummium. Carthage mint, regnal year 14 (A.D. 540-1). Obverse is worn and pitted, and possibly overstruck.' Weight 4.96g. Diameter (oval flan) 17-18.5mm. Die axis 280°. References: MIB(I) 199; DO 297-8. 2. Justin I (A.D. 518-27), bronze follis. Probably Constantinople mint. Considerable wear to both sides. Mintmark in exergue very worn but possibly CON. Weight 15.81g. Diameter 28mm. Die axis 170° (approx.). References: MIB(I) 11; DO 8e. 3. Maurice Tiberius (A.D. 582-602), bronze follis. Constantinople mint, regnal year 19 (A.D. 600 1). 1 This piece is referred to in G. C. Boon, 'Byzantine and other exotic ancient bronze coins from Exeter', in N. Holbrook and P. T. Bidwell, Roman finds from Exeter, Exeter Archaeological Reports, IV (Exeter, 1991), pp. 41,43. 198 Robert A. Philpott Unevenly struck and worn; dark greenish-brown patina. The lower parts of the design on the obverse (especially around the orb and left of the portrait) have an irregular series of old scratch marks of which a few extend across the higher relief parts of the design. Weight 11.13g. Diameter 28mm. Die axis 210°. References: MIB(II) 67D-'; DO 26-43. DISCUSSION The first of these coins, a small bronze of Justinian I, was reported in 1987 by a resident of Borrowdale Road, Moreton (National Grid Reference SJ 259896), who was prompted to contact the author as a result of the interest aroused in an archaeological excavation under way near by in Hoylake Road, Moreton. -

A Case for Ecclesiastical Minting of Anglo-Viking Coins

A Case for Ecclesiastical Minting of Anglo-Viking Coins Thesis by Joseph Schneider Advised by Professor Warren Brown In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of History CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Background: Coinage in Pre-Viking Anglo-Saxon England ............................................................................ 4 Background: Viking Settlement of England ................................................................................................ 12 Anglo-Viking Coinages: The Question of Ecclesiastical Minting ................................................................. 15 A Survey of Anglo-Viking Coins ................................................................................................................... 21 The Case for Ecclesiastical Coinage ............................................................................................................. 33 The Danelaw Church ................................................................................................................................... 42 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 46 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................