A Viking Find from the Isle of Texel (Netherlands) and Its Implications Ijssennagger, Nelleke L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections Development Policy

Collections Development Policy Harris Museum & Art Gallery Preston City Council Date approved: December 2016 Review date: By June 2018 The Harris collections development policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, currently every 12-18 months while the Re-Imagining the Harris project develops. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the collections development policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of the Harris’ collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant policies/plans of the organisation: The Collections Development Policy should be read in the wider context of the Harris’ Documentation Policy and Documentation Plan, Collections Care and Conservation Policy, Access Policy Statement and the Harris Plan. 1.1. The Harris’ statement of purpose is: The Re-Imagining the Harris project builds on four key principles of creativity, democracy, animation and permeability to create an open, flexible and responsive cultural hub led by its communities and inspired by its collections. 1.2. Preston City Council will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3. By definition, the Harris has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. Preston City Council therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in the Harris’ collection. 1.4. Acquisitions outside the current stated policy will only be made in exceptional circumstances. 1.5. The Harris recognises its responsibility, when acquiring additions to its collections, to ensure that care of collections, documentation arrangements and use of collections will meet the requirements of the Museum Accreditation Standard. -

Annual Report Fishing for Litter 2011

Annual Report Fishing for Litter 2011 Fishing For Litter Annual Report Fishing for Litter project 2011 Edited by KIMO Nederland en België March 2012 Bert Veerman Visual design: Baasimmedia Annual Report Fishing for Litter project 2011 Index: Pag: Message from the Chairman ................................................................................................. 5 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 2.0 Project description ................................................................................................... 8 3.0 Goals of the project .................................................................................................. 9 4.0 Monitors ................................................................................................................ 10 4.1 Waste from the beaches of Ameland ......................................................... 10 4.2 Waste through the ports ............................................................................ 10 5.0 Consultation structure ............................................................................... 11 6.0 Administration ........................................................................................... 11 7.0 Publicity .................................................................................................... 11 7.1 Documentary “Fishing for Litter” ................................................................ 11 8.0 A summary of activities -

Wieringen, Het Geheime Eiland

Aardkundig excursiepunt 9 CEES DE JONG Tapuitlaan 96, 7905 CZ Hoogeveen, [email protected] WIERINGEN, HET GEHEIME EILAND 10 GRONDBOOR & HAMER NR 1 - 2007 Naam: over de stuwwal heen ligt gedeeltelijk is geërodeerd, zijn Wieringen op tal van plaatsen veel zwerfstenen te zien. Bij eb kan men op de wadplaten aan de noordzijde van het eiland, Locatie: waar de keileem dicht onder het oppervlak ligt, nog al• Provincie Noord-Holland, Gemeente Wieringen. lerlei soorten zwerfstenen vinden. Om bezoekers behulpzaam te zijn bij het verkennen van Bereikbaarheid: het eiland zijn een viertal fietsroutes uitgezet en een Het voormalige eiland Wieringen is gelegen aanslui• viertal wandelroutes. Door gebruik te maken van deze tend aan de noordkant van de Wieringermeerpolder. routes maakt men kennis met Wieringen op het gebied Het is via de N99 bereikbaar vanuit het Oosten vanaf van de natuur en de cultuur. Al fietsend of wandelend de Afsluitdijk en vanuit het Westen langs het Amstel- krijgt men te maken met een glooiend landschap met meer. Voorts kan men het vanuit het zuiden via de A7 (naast de hoofdweg N99) smalle slingerende weggetjes bij Den Oever bereiken. Het informatiepaneel staat op omzoomd door meidoornhagen. Over de gehele lengte• x = 123,7, y = 545,2 iets ten noorden van het kerkje van richting van het eiland zijn verhogingen te zien. Dat zijn Westerland (afb. 2). de door het landijs gevormde stuwwallen. Met name bij Oosterland, Stroe (afb. 4) en Westerland (afb. 5) zijn ze Toegankelijkheid: goed zichtbaar. Over het gehele eiland zijn vele zwerf• Het voormalig eiland Wieringen is normaal toegankelijk. stenen te zien en te vinden. -

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

An Aspect of Die-Production in the Middle Anglo-Saxon Period: the Use of Guidelines in the Cutting of Die-Faces

M. ARCHIBALD: An aspect of die-production in the middle Anglo-Saxon..., VAMZ, 3. s., XLV (2012) 37 MARION ARCHIBALD Department of Coins and Medals The British Museum Great Russell Street London WC1B 3DG, UK [email protected] AN ASPECT OF DIE-PRODUCTION IN THE MIDDLE ANGLO-SAXON PERIOD: THE USE OF GUIDELINES IN THE CUTTING OF DIE-FACES UDK: 671.4.02(410.1)»08/09« Izvorni znanstveni rad Felicitating Ivan Mirnik on his seventieth birthday and congratulating him on his major contribution to numismatics, both as a scholar and as cura- tor of the Croatian national collection in the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, I offer this contribution on a technical aspect of our subject which I know, from conversations during his many visits to London, is among his wide-ranging interests. Key words: England, Anglo-Saxon, coin, die, die-face, guidelines, dividers, York. Ključne riječi: Engleska, anglosaksonski, novac, punca, udarna površina punce, smjernice, prečke, York. Uniformity of appearance is desirable in a coinage to enable users to distinguish official issues from counterfeits on sight, and one of the ways to achieve this is to standardise as far as possible the methods of production. Contemporary references to ancient coining methods are virtually non-existent. The most informative account is by the South Arabian al-Hamdânî writ- ing in the first half of the tenth century (TOLL 1970/1971: 129-131; 1990). On the preparation of the die-face he mentions the use of dividers to fix the centre. For the Anglo-Saxon period in England there are no early written sources whatsoever on this subject and we have to rely on a 38 M. -

The Cultural Heritage of the Wadden Sea

The Cultural Heritage of the Wadden Sea 1. Overview Name: Wadden Sea Delimitation: Between the Zeegat van Texel (i.e. Marsdiep, 52° 59´N, 4° 44´E) in the west, and Blåvands Huk in the north-east. On its seaward side it is bordered by the West, East and North Frisian Islands, the Danish Islands of Fanø, Rømø and Mandø and the North Sea. Its landward border is formed by embankments along the Dutch provinces of North- Holland, Friesland and Groningen, the German state of Lower Saxony and southern Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein. Size: Approx. 12,500 square km. Location-map: Borders from west to east the southern mainland-shore of the North Sea in Western Europe. Origin of name: ‘Wad’, ‘watt’ or ‘vad’ meaning a ford or shallow place. This is presumably derives from the fact that it is possible to cross by foot large areas of this sea during the ebb-tides (comparable to Latin vadum, vado, a fordable sea or lake). Relationship/similarities with other cultural entities: Has a direct relationship with the Frisian Islands and the western Danish islands and the coast of the Netherlands, Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and south Denmark. Characteristic elements and ensembles: The Wadden Sea is a tidal-flat area and as such the largest of its kind in Europe. A tidal-flat area is a relatively wide area (for the most part separated from the open sea – North Sea ̶ by a chain of barrier- islands, the Frisian Islands) which is for the greater part covered by seawater at high tides but uncovered at low tides. -

Viking: Rediscover the Legend

Highlights from Viking: Rediscover the Legend A British Museum and York Museums Trust Partnership Exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery 9 February to 8 September 2019 1.The Cuerdale Hoard Buried Circa 904AD Made up of more than 8,600 items including silver coins, English and Carolingian jewellery, hacksilver and ingots, the Cuerdale Hoard is one of the largest Viking hoards ever found. The bulk of the hoard is housed at the British Museum. It was discovered on 15 May 1840 on the southern bank of a bend of the River Ribble, in an area called Cuerdale near to Preston, in Lancashire. It is four times in size and weight than any other in the UK and second only to the Spillings Hoard found on Gotland, Sweden. The hoard is thought to have been buried between 903 and 910 AD, following the expulsion of Vikings from Dublin in 902. The area of discovery was a popular Viking route between the Irish Sea and York. Experts believe it was a war chest belonging to Irish Norse exiles intending to reoccupy Dublin from the Ribble Estuary. 2. The Vale of York Hoard Buried 927–928AD The Vale of York Viking Hoard is one of the most significant Viking discoveries ever made in Britain. The size and quality of the material in the hoard is remarkable, making it the most important find of its type in Britain for over 150 years. Comprising 617 coins and almost 70 pieces of jewellery, hack silver and ingots, all contained with a silver-gilt cup; it tells fascinating stories about life across the Viking world. -

Het Recreatielandschap Van Ameland

Het recreatielandschap van Ameland Een interdisciplinair onderzoek naar de historische ontwikkeling van de relatie tussen de recreatie en het landschap op Ameland tussen 1855 en 1980 Robin Weiland Voorblad: Duinoord 1929. Familie Postma:Jacob Postma en Hiske Westhof met hun kinderen Metty, Klaas, Jelly, Jan en Grietje (en nog meer families). Foto is van Jaap Postma, zoon van Jan. Het Postmapad is naar hen vernoemd. 1e overgang vanaf de Strandweg. (Amelander historie) Opgeweld uit wier en zand gans omspoeld door zilte baren Moge God het steeds bewaren ons plekje, rijk aan duin en strand het ons zo lieve Ameland! 2 Kollum, april 2019. Auteur: Robin Weiland Masterscriptie Landschapsgeschiedenis Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Scriptiebegeleider: prof. dr. ir. Th. (Theo) Spek (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) Tweede lezer: drs. Anne Wolff (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) Het recreatielandschap van Ameland Een interdisciplinair onderzoek naar de historische ontwikkeling van de relatie tussen de recreatie en het landschap op Ameland tussen 1852 en 1980 3 Samenvatting Recreatie is een betrekkelijk nieuw verschijnsel, dat echter zijn stempel stevig op het landschap heeft gedrukt. Dit onderzoek richt zich op de recreatie aan zee, specifiek op het eiland Ameland. Hoe is de recreatie hier ontstaan, hoe reguleerde de lokale, regionale en nationale overheden de toeristenstroom en hoe pasten de Amelanders de recreatie in in de beperkte ruimte die het eiland verschaft? In het eerste deel staat het landschap van Ameland centraal. Hoe is Ameland ontstaan en met welke omstandigheden hebben de eilanders te doen gehad? Ook wordt er uiteengezet welke bodemtypen Ameland bevat en hoe een standaardeiland is opgebouwd. Dit verklaart de ligging van de dorpen en schijnt een licht op waar de ruimtelijke kansen voor recreatie lagen. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering -

Geology of the Dutch Coast

Geology of the Dutch coast The effect of lithological variation on coastal morphodynamics Deltores Title Geology of the Dutch coast Client Project Reference Pages Rijkswaterstaat Water, 1220040-007 1220040-007-ZKS-0003 43 Verkeer en Leefomgeving Keywords Geology, erodibility, long-term evolution, coastal zone Abstract This report provides an overview of the build-up of the subsurface along the Dutch shorelines. The overview can be used to identify areas where the morphological evolution is partly controlled by the presence of erosion-resistant deposits. The report shows that the build-up is heterogeneous and contains several erosion-resistant deposits that could influence both the short- and long-term evolution of these coastal zones and especially tidal channels. The nature of these resistant deposits is very variable, reflecting the diverse geological development of The Netherlands over the last 65 million years. In the southwestern part of The Netherlands they are mostly Tertiary deposits and Holocene peat-clay sequences that are relatively resistant to erosion. Also in South- and North-Holland Holocene peat-clay sequences have been preserved, but in the Rhine-Meuse river-mouth area Late Pleistocene• early Holocene floodplain deposits form additional resistant layers. In northern North-Holland shallow occurrences of clayey Eemian-Weichselian deposits influence coastal evolution. In the northern part of The Netherlands it are mostly Holocene peat-clay sequences, glacial till and over consolidated sand and clay layers that form the resistant deposits. The areas with resistant deposits at relevant depths and position have been outlined in a map. The report also zooms in on a few tidal inlets to quick scan the potential role of the subsurface in their evolution. -

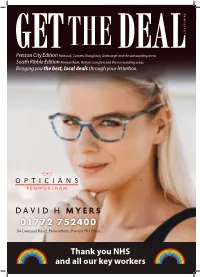

Thank You NHS and All Our Key Workers

GET THE DEAL ASHIRE C N A L Preston City Edition Fulwood, Cottam, Broughton, Grimsargh and the surrounding areas. South Ribble Edition Penwortham, Hutton, Longton and the surrounding areas. Bringing you the best, local deals through your letterbox. PENWORTHAM 01772 752400 34 Liverpool Road, Penwortham, Preston PR1 0DQ Thank you NHS and all our key workers GET THE DEAL • JULY 2020 | 1 WE WON’T BE BEATEN ON PRICE! FRESHEN UP OR UNWIND IN ONE OF MANY BATHROOM SUITES AVAILABLE TODAY FREE DESIGN SERVICE AVAILABLE Units 3 & 4, Preston Trade Park, Ribbleton Lane, Preston PR1 5AU T: 01772 651 500 PRESTON E: [email protected] www.howdens.com 2 | GET THE DEAL • JULY 2020 WE WON’T BE BEATEN ON PRICE! Contents Hello to everyone and welcome back to the July edition of Get the Deal Lancashire magazine. While we have all been adjusting to a new way of living it has given all of us a chance to FRESHEN UP OR UNWIND appreciate our surroundings. As we look forward to Summer hopefully IN ONE OF MANY BATHROOM SUITES we can re-connect with our AVAILABLE TODAY FREE local businesses who have DESIGN SERVICE been affected over the last AVAILABLE few months, we wish them all well. In this edition we have a feature from the Friends of Winckley Square and our regular recipes from Booths. We hope you enjoy this edition and we look forward Download our App. to our next edition in Search for “The Prestige” September. Best Wishes Michael Units 3 & 4, Preston Trade Park, Ribbleton Lane, Preston PR1 5AU 4 Priory Lane, Penwortham, Preston PR1 0AR Disclaimer T: 01772 651 500 www.theprestigebarbershop.co.uk All advertisiments are carefully checked when compiling Get-the-Deal Lancashire magazine. -

The Danes in Lancashire

Th e D a n es i n La nc as hi re a nd Yorks hi re N GTO N S . W . PARTI n ILLUSTRATED SHERRATT HUGHES n n : Soh o u a Lo do 3 3 Sq re, W. M a n chester : 34 Cros s Street I 909 P R E FACE . ‘ ’ ' THE s tory of th e childhood of our race who inh a bited th e counties of L a nca shire a n d Yorkshire before th e a t a n a m a a to th e Norm n Conques , is l ost bl nk p ge a a to-da a a popul r re der of y . The l st inv ders of our a a s h e a a n d shores , whom we design te t D nes Norsemen , not a n were the le st importa t of our a ncestors . The t t a a a t a n d u t H is ory of heir d ring dventures , cr f s c s oms , s a n d a a t th e t a belief ch r cter , wi h surviving r ces in our a a a n d a th e t t . l ngu ge l ws , form subjec of his book the a nd e From evidence of relics , of xisting customs a n d t a t t ac a n d a s r di ions , we r e their thought ction , their t a n d a a t a n d th e m firs steps in speech h ndicr f , develop ent e at o a of their religious conc ptions .