Steering Through the Great Depression: Institutions, Expectations, and the Change of Macroeconomic Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS September 1935

SEPTEMBER 1935 OF CURRENT BUSINE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 15 NUMBER 9 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES MINERALS YEARBOOK 1935 The First Complete Official Record Issued in 1935 A LIBRARY OF CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE MINERAL INDUSTRY (In One Volume) Survey of gold and silver mining and markets Detailed State mining reviews Current trends in coal and oil Analysis of the extent of business recovery for vari- ous mineral groups 75 Chapters ' 59 Contributors ' 129 Illustrations - about 1200 Pages THE STANDARD AUTHENTIC REFERENCE BOOK ON THE MINING INDUSTRY CO NT ENTS Part I—Survey of the mineral industries: Secondary metals Part m—Konmetals- Lime Review of the mineral industry Iron ore, pig iron, ferro'alloys, and steel Coal Clay Coke and byproducts Abrasive materials Statistical summary of mineral production Bauxite e,nd aluminum World production of minerals and economic Recent developments in coal preparation and Sulphur and pyrites Mercury utilization Salt, bromine, calcium chloride, and iodine aspects of international mineral policies Mangane.se and manganiferous ores Fuel briquets Phosphate rock Part 11—Metals: Molybdenum Peat Fuller's earth Gold and silver Crude petroleum and petroleum products Talc and ground soapstone Copper Tungsten Uses of petroleum fuels Fluorspar and cryolite Lead Tin Influences of petroleum technology upon com- Feldspar posite interest in oil Zinc ChroHHtt: Asbestos -

OAC Review Volume 47 Issue 5, February 1935

CONTENTS FOR FEBRUARY■BRUARY, 1935 Professor Rigby Finds Him¬ College Life self (A Story) Macdonald News Short Notes on Little Things “Attention! Mac Hall”—A At the Pig-Fair Warning The Reclaiming of the Zuiderzee College Royal Hints English Youth Hostels Alumni News Kew Gardens Sportsfolio VOL. XLVII O. A. C., GUELPH NO. 5 PHOTOS GLASSES For Clear, PORTRAITS Comfortable and Vision GROUPS - - - A careful, thorough and scientific Examination. - - - The use of only the highest quality Materials. FRAMES -Prompt and efficient Service. Assures you of Complete Satisfaction TheO’Keeffes’ Studio A. D. SAVAGE Since 1907 Upper Wyndham St. Guelph's Leading Optometrist Phone 942 SAVAGE BLDG., GUELPH Phone 1091w ^ There is nothing as refreshing as a dish of GOOD Ice Cream. They have it at the Tuck Shop—Fast-frozen, smooth, de¬ licious—Of course it’s “SERVICE” our Hobby—'“QUALITY” our Pride THE O. A. C. REVIEW 257 Guelph Radial Railway We have enjoyed serving you in the Past and we look forward to the Future. Low own-payment easy terms Ford s*i es an rvice Ask the “Aggies ' PHONE 292 23 -27 Cork Str They'll tell you DRIVE THE V-l TODAY The BOND HARDWARE CO., Limited WM. ROGERS and 1847 ROGERS ELECTRIC APPLIANCE SILVER PLATE Hot Point Electric Irons .$3.50 up in very attractive patterns Hot Point Turnover Toasters .... 4.40 Electric Perculators . 3.00 up Flat Toasters . .60 up HOLLOW WARE SILVER Upright Toasters . 1.75 up i Sandwich Grills . 2.50 Tea Services, Flower Baskets, Casseroles, Curling Irons . 1.00 up Pie Plates, Entree Dishes and Trays Electric Iron and cord . -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The Political Economy of Argentina's Abandonment

Going through the labyrinth: the political economy of Argentina’s abandonment of the gold standard (1929-1933) Pablo Gerchunoff and José Luis Machinea ABSTRACT This article is the short but crucial history of four years of transition in a monetary and exchange-rate regime that culminated in 1933 with the final abandonment of the gold standard in Argentina. That process involved decisions made at critical junctures at which the government authorities had little time to deliberate and against which they had no analytical arsenal, no technical certainties and few political convictions. The objective of this study is to analyse those “decisions” at seven milestone moments, from the external shock of 1929 to the submission to Congress of a bill for the creation of the central bank and a currency control regime characterized by multiple exchange rates. The new regime that this reordering of the Argentine economy implied would remain in place, in one form or another, for at least a quarter of a century. KEYWORDS Monetary policy, gold standard, economic history, Argentina JEL CLASSIFICATION E42, F4, N1 AUTHORS Pablo Gerchunoff is a professor at the Department of History, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] José Luis Machinea is a professor at the Department of Economics, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] 104 CEPAL REVIEW 117 • DECEMBER 2015 I Introduction This is not a comprehensive history of the 1930s —of and, if they are, they might well be convinced that the economic policy regarding State functions and the entrance is the exit: in other words, that the way out is production apparatus— or of the resulting structural to return to the gold standard. -

Commodity Price Movements in 1936 by Roy G

March 1937 March 1937 SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS 15 Commodity Price Movements in 1936 By Roy G. Blakey, Chief, Division of Economic Research HANGES in the general level of wholesale prices to 1933 also rose most rapidly during 1936 as they did C during the first 10 months of 1936 were influenced in the preceding 3 years. (See fig. 1.) mostly by the fluctuations of agricultural prices, with The annual index of food prices was 1.9 percent lower nonagricultural prices moving approximately horizon- for 1936 than for 1935, but the index of farm products tally. Agricultural prices, after having risen sharply as was 2.7 percent and the index of prices of all commodi- a result of the 1934 drought, moved lower during the ties other than farm products and foods was 2.2 per- first 4% months of 1936 on prospects for increased INDEX NUMBERS (Monthly average, 1926= lOO) supplies. When the 1936 trans-Mississippi drought 1201 • • began to appear serious, however, agricultural prices turned up sharply and carried the general price average -Finished Products with them. The rapid rise during the summer was suc- / ceeded by a lull in September and October, but imme- 60 diately following the November election there was a -Row Maferia/s sharp upward movement of most agricultural prices at the same time that a marked rise in nonagricultural products was experienced. The net result of these 1929 1930 1952 1934 I9?6 divergent movements was a 1-percent increase in the Figure 1.—Wholesale Prices by Economic Classes, 1929-36 (United 1936 annual average of the Bureau of Labor Statistics States Department of Labor). -

Maine Alumnus, Volume 11, Number 3, December 1929

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines University of Maine Publications 12-1929 Maine Alumnus, Volume 11, Number 3, December 1929 General Alumni Association, University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation General Alumni Association, University of Maine, "Maine Alumnus, Volume 11, Number 3, December 1929" (1929). University of Maine Alumni Magazines. 99. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines/99 This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PURCHASING AGENT UN IV. OF ME. ORONO, ME. Coburn H all Volume 1 1 December, 1929 Number 3 University L oyalty to A lu m n i “The game of last Saturday with Colby will go down in my memory as one of the outstanding contests played by a Maine team. I have never seen a better example of ‘Maine spirit’, clean playing, and determination to win. That we lost is no disgrace. Everyone who saw the game should be proud of the team and of the fact that even against heavy odds every moment was full of fight and aggressiveness.” This message was sent to the student body by President Boardman en route to Chicago and the Pacific Coast. Presi dent Boardman was authorized by unanimous vote of the Board of Trustees to make this 6000 mile coast-to-coast trip for the purpose of carrying the spirit and news of the Univer sity to the Alumni Associations of the middle west and Pacific coast and to bring back to the campus the spirit of the far west ern alumni associations. -

The Foreign Service Journal, December 1929

THfe AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL CARACAS, VENEZUELA Entrance to Washington Building, in which the American Consulate is located Vol. VI DECEMBER, 1929 No. 12 BANKING AND INVESTMENT SERVICE THROUGHOUT THE WORLD The National City Bank of New York and Affiliated Institutions THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK CAPITAL, SURPLUS AND UNDIVIDED PROFITS $238,516,930.08 (AS OF OCTOBER 4, 1929) HEAD OFFICE THIRTY-SIX BRANCHES IN 56 WALL STREET. NEW YORK GREATER NEW YORK Foreign Branches in ARGENTINA . BELGIUM . BRAZIL . CHILE . CHINA . COLOMBIA . CUBA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC . ENGLAND . INDIA . ITALY . JAPAN . MEXICO . PERU . PORTO RICO REPUBLIC OF PANAMA . STRAITS SETTLEMENTS . URUGUAY . VENEZUELA. THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK (FRANCE) S. A. Paris 41 BOULEVARD HAUSSMANN 44 AVENUE DES CHAMPS ELYSEES Nice: 6 JARDIN du Roi ALBERT ler INTERNATIONAL BANKING CORPORATION (OWNED BY THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK Foreign and Domestic Branches in UNITED STATES . PHILIPPINE ISLANDS . SPAIN . ENGLAND and Representatives in The National City Bank Chinese Branches. BANQUE NATIONALE DE LA REPUBLIQUE D’HAITI . (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: PORT AU-PRINCE, HAITI CITY BANK FARMERS TRUST COMPANY {formerly The farmers* Loan and Trust Company—now affiliated with The National City Bank of New York) Head Office: 22 WILLIAM STREET, NEW YORK Temporary Headquarters: 45 EXCHANGE PLACE THE NATIONAL CITY COMPANY (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) HEAD OFFICE OFFICES IN SO LEADING 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK AMERICAN CITIES Foreign Offices: LONDON . AMSTERDAM . COPENHAGEN . GENEVA . TOKIO . SHANGHAI Canadian Offices: MONTREAL . -

Federal Reserve Bulletin June 1935

FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN JUNE 1935 ISSUED BY THE FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD AT WASHINGTON Business and Credit Conditions Industrial Advances by Federal Reserve Banks Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1935 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD Ex-officio members: MARRINER S. ECCLES, Governor. HENRY MORGENTHAU, Jr., J. J. THOMAS, Vice Governor. Secretary of the Treasury, Chairman, CHARLES S. HAMLIN. J. F. T. O'CONNOR, ADOLPH C. MILLER. Comptroller of the Currency. GEORGE R. JAMES. M. S. SZYMCZAK. LAWRENCE CLAYTON, Assistant to the Governor. LAUCHLIN CURRIE, Assistant Director, Division of ELLIOTT L. THURSTON, Special Assistant to the Governor. Research and Statistics. CHESTER MORRILL, Secretary. WOODLIEF THOMAS, Assistant Director, Division of J. C. NOELL, Assistant Secretary. Research and Statistics. LISTON P. BETHEA, Assistant Secretary. E. L. SMEAD, Chief, Division of Bank Operations. S. R. CARPENTER, Assistant Secretary. J. R. VAN FOSSEN, Assistant Chief, Division of Bank WALTER WYATT, General Counsel. Operations. GEORGE B. VEST, Assistant General Counsel. J. E. HORBETT, Assistant Chief, Division of Bank B. MAGRUDER WINGFIELD, Assistant General Counsel. Operations. LEO H. PAULGER, Chief, Division of Examinations. CARL E. PARRY, Chief, Division of Security Loans. R. F. LEONARD, Assistant Chief, Division of Examina- PHILIP E. BRADLEY, Assistant Chief, Division of Security tions. Loans. C. E. CAGLE, Assistant Chief, Division of Examinations. O. E. FOULK, Fiscal Agent. FRANK J. DRINNEN, Federal Reserve Examiner. JOSEPHINE E. LALLY, Deputy Fiscal Agent. E. A. GOLDENWEISER, Director, Division of Research and Statistics. FEDERAL ADVISORY COUNCIL District no. -

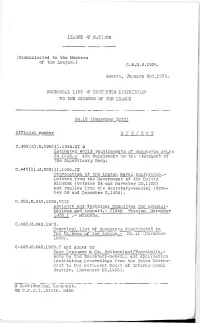

C.6.M.5.1936. Geneva, January 2Nd,1936<, NUMERICAL LIST OF

LEAGUE OF NATIONS (Communicated to the Members of the League.) C.6.M.5.1936. Geneva, January 2nd,1936<, NUMERICAL LIST OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO THE MEMBERS OF THE LEAGUE No.12 (December 1935) Officiel number S U B J E__C T C.462(d).M,198(d).1934.XI ® Estimated world requirements of dangerous drugs in 1955,- 4th Supplement to the statement of the Supervisory Body. C.445(1).M.233(1).1935.IX Convocation of the London Nava 1 Conf e ren c e_, - Letters from the Government of the United Kingdom (October 24 and November 30,1935) and replies from the Secretary-General (Octo ber 30 and December 2,1935). C .458.M.240.1935.VIII Advisory and Technical Comraittee for communi cations and transit.-- (19th bession, November 1935.) . - Records. C.462.M.242.1935. Numerical list of documents distributed_to the Members of the League,- No.il (November 1935). C.463.M.243,1935„V and Annex @3 Case Lo singer & Co. Sw i tz_e r] .and/Yugos lav la. - Nore by the Secretary-General and Application instituting proceedings from the Swiss Govern ment to the Permanent Court of International Justifie. (November 23,1935). @ Confidential document. C.P.J.I.,Distr. 3420 - 2 - Cv464.M.244.1935.Ill and Annex @ In te r-G_) vernmen t al Conference on. _ b i_o1 o^ioal ste.ndardJ. sati on J October 1935).- I-lote by the Secretary-General and report. C.467.M.245,1935.VII Dlsp ute bet ween Et h lopi a. a rid _It aly Tel eg ram from the Ethiopian Government (December 2, 1935), C.469,IVU246» 1935»V and Erratum to numbering, @@ Composition of the_ Çhamb er _ f or Suinma ry_ Pro ce - du rn_ o f the P e rmane nt_ Court of International _ Justice.- Note by the éucretary-Generaï. -

Special Libraries, April 1935

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1935 Special Libraries, 1930s 4-1-1935 Special Libraries, April 1935 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1935 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, April 1935" (1935). Special Libraries, 1935. 4. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1935/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1930s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1935 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I SPECIAL LIBRARIES "Putting Knowledge to Work" - - VOLUME 26 APRIL 9935 NUMBER 4 University Press and the Special Library-Joseph A. Duffy, Jr.. 83 Membership Campaign-Your Share in It-Adeline M. Macrum . 85 To Aid Collectors of Municipal Documents-Josephine 6. Hollingsworth . 86 Reading Notes. .. 87 Special Libraries Directory of United States and Canada . 88 Special Library Survey The Banking LibraryAlta B. Claflin. 90 I Conference News. .. 93 Nominating Committee Report . 95 Snips and Snipes. '. , . , 96 "We Do This". 97 Business Book Review Digest . 98 Whither Special Library Classifications? . 99 New Books Received . 100 Publications of Special Interest. 101 Duplicate Exchange List. , . 104 indexed in industrial Arts index and Public Affairs information Service SPECIAL LIBRARIES published monthly September to April with bi-month1 isrues May to August, by The S ecial Libraries Assodation at 10 Fen streit Concord, N. k. Subscri tion Offices, 10 Fen &met, Concord, N. -

An Earthquake Hits STAMPEX: Quetta 1935

An Earthquake hits STAMPEX: Quetta 1935 Building an Exhibit from a Tragedy Contributed by Neil Donen Neil with his ‘salt of the earth’ philatelic wife Nancy Number 3.2 October 2018 A Rare Opportunity - not to be Missed Sometimes we are presented with an opportunity which just we cannot pass up. It is a foolish man who will turn this down. So when Neil Donen agreed that we could share his Exhibit on the Quetta Earthquake, displayed at the Autumn 2018 STAMPEX with us, it was one of those moments. I was more than delighted to welcome an authoritative and insightful addition to our third set of Occasional Papers Neil’s display fitted the agenda set for our Occasional Publications perfectly: • It tells a story which is compellingly interesting; • It introduces what is for many, a new angle on Indian Philately; • It puts humanity at the centre where we can find examples of bravery, resourcefulness, empathy, organizational capacity, kindness and essential optimism; • It is a self-contained fragment from history; • It is a study which can be limited to just 14 days or be extended into the days and years preceding the earthquake and into the aftermath of its consequences; • It poses many unanswered questions which will require further research and thought to reach a conclusion. Many members of the ISC will already have read some of the research work already undertaken by Neil Donen in India Post 52/2 (2018) No. 207. He makes a compelling case for research in these misty areas to be undertaken on a collaborative basis. -

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Typescript records of programmes, 1935-54, broadcast by the BBC Scottish Region (later Scottish Home Service). 1. February-March, 1935. 2. May-August, 1935. 3. September-December, 1935. 4. January-April, 1936. 5. May-August, 1936. 6. September-December, 1936. 7. January-February, 1937. 8. March-April, 1937. 9. May-June, 1937. 10. July-August, 1937. 11. September-October, 1937. 12. November-December, 1937. 13. January-February, 1938. 14. March-April, 1938. 15. May-June, 1938. 16. July-August, 1938. 17. September-October, 1938. 18. November-December, 1938. 19. January, 1939. 20. February, 1939. 21. March, 1939. 22. April, 1939. 23. May, 1939. 24. June, 1939. 25. July, 1939. 26. August, 1939. 27. January, 1940. 28. February, 1940. 29. March, 1940. 30. April, 1940. 31. May, 1940. 32. June, 1940. 33. July, 1940. 34. August, 1940. 35. September, 1940. 36. October, 1940. 37. November, 1940. 38. December, 1940. 39. January, 1941. 40. February, 1941. 41. March, 1941. 42. April, 1941. 43. May, 1941. 44. June, 1941. 45. July, 1941. 46. August, 1941. 47. September, 1941. 48. October, 1941. 49. November, 1941. 50. December, 1941. 51. January, 1942. 52. February, 1942. 53. March, 1942. 54. April, 1942. 55. May, 1942. 56. June, 1942. 57. July, 1942. 58. August, 1942. 59. September, 1942. 60. October, 1942. 61. November, 1942. 62. December, 1942. 63. January, 1943.