UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floor, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai 400 005 Tel

Before the MAHARASHTRA ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION World Trade Centre, Centre No.1, 13th Floor, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai 400 005 Tel. 022 22163964/65/69 Fax 22163976 Email: [email protected] Website: www.merc.gov.in Case No. 202 of 2020 Suo Motu Proceeding in the matter of Grid Failure in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region on 12 October 2020 at 10.02 Hrs. Coram I.M. Bohari, Member Mukesh Khullar, Member Parties to the proceeding 1. Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Co. Ltd. 2. Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Co. Ltd. 3. BEST Undertaking 4. Maharashtra State Load Dispatch Centre 5. State Transmission Utility 6. Tata Power Company Ltd.-Generation 7. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Transmission 8. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Distribution 9. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.- Generation 10. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd. -Transmission 11. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.-Distribution 12. Indian Railways 13. Mindspace Business Parks Pvt. Ltd. 14. Gigaplex Estate Pvt. Ltd. Appearance (All Representatives) 1. Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Co. Ltd. …… Shri Sanjay Taksande 2. Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Co. Ltd. …….Shri Paresh Bhagwat 3. BEST Undertaking …….Shri N.N. Chaugule 4. Maharashtra State Load Dispatch Centre …… Shri S.V. Jaltare 5. State Transmission Utility …….Shri S.V. Jewalikar 6. Tata Power Company Ltd.-Generation 7. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Transmission ……Shri Devanand Pallikuth 8. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Distribution 9. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.- Generation ….. Shri Mahesh Bhadoria MERC Order in Case No. 202 of 2020 Page 1 of 24 10. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd. -Transmission ..…. Shri Dilip Devasthale 11. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.-Distribution … . Shri Shrikant Yeole …… Shri Kapil Sharma …… Shri Kishor Patil 12. -

Detailed Project Report Extension of Mumbai Metro Line-4 from Kasarvadavali to Gaimukh

DETAILED PROJECT REPORT EXTENSION OF MUMBAI METRO LINE-4 FROM KASARVADAVALI TO GAIMUKH MUMBAI METROPOLITAN REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (MMRDA) Prepared By DELHI METRO RAIL CORPORATION LTD. October, 2017 DETAILED PROJECT REPORT EXTENSION OF MUMBAI METRO LINE-4 FROM KASARVADAVALI TO GAIMUKH MUMBAI METROPOLITAN REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (MMRDA) Prepared By DELHI METRO RAIL CORPORATION LTD. October, 2017 Contents Pages Abbreviations i-iii Salient Features 1-3 Executive Summary 4-40 Chapter 1 Introduction 41-49 Chapter 2 Traffic Demand Forecast 50-61 Chapter 3 System Design 62-100 Chapter 4 Civil Engineering 101-137 Chapter 5 Station Planning 138-153 Chapter 6 Train Operation Plan 154-168 Chapter 7 Maintenance Depot 169-187 Chapter 8 Power Supply Arrangements 188-203 Chapter 9 Environment and Social Impact 204-264 Assessment Chapter 10 Multi Model Traffic Integration 265-267 Chapter 11 Friendly Features for Differently Abled 268-287 Chapter 12 Security Measures for a Metro System 288-291 Chapter 13 Disaster Management Measures 292-297 Chapter 14 Cost Estimates 298-304 Chapter 15 Financing Options, Fare Structure and 305-316 Financial Viability Chapter 16 Economical Appraisal 317-326 Chapter 17 Implementation 327-336 Chapter 18 Conclusions and Recommendations 337-338 Appendix 339-340 DPR for Extension of Mumbai Metro Line-4 from Kasarvadavali to Gaimukh October 2017 Salient Features 1 Gauge 2 Route Length 3 Number of Stations 4 Traffic Projection 5 Train Operation 6 Speed 7 Traction Power Supply 8 Rolling Stock 9 Maintenance Facilities -

Exploration of Portuguese-Bengal Cultural Heritage Through Museological Studies

Exploration of Portuguese-Bengal Cultural Heritage through Museological Studies Dr. Dhriti Ray Department of Museology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Line of Presentation Part I • Brief history of Portuguese in Bengal • Portuguese-Bengal cultural interactions • Present day continuity • A Gap Part II • University of Calcutta • Department of Museology • Museological Studies/Researches • Way Forwards Portuguese and Bengal Brief History • The Portuguese as first European explorer to visit in Bengal was Joao da Silveira in 1518 , couple of decades later of the arrival of Vasco Da Gama at Calicut in 1498. • Bengal was the important area for sugar, saltpeter, indigo and cotton textiles •Portuguese traders began to frequent Bengal for trading and to aid the reigning Nawab of Bengal against an invader, Sher Khan. • A Portuguese captain Tavarez received by Akbar, and granted permission to choose any spot in Bengal to establish trading post. Portuguese settlements in Bengal In Bengal Portuguese had three main trade points • Saptagram: Porto Pequeno or Little Haven • Chittagong: Porto Grande or Great Haven. • Hooghly or Bandel: In 1599 Portuguese constructed a Church of the Basilica of the Holy Rosary, commonly known as Bandel Church. Till today it stands as a memorial to the Portuguese settlement in Bengal. The Moghuls eventually subdued the Portuguese and conquered Chittagong and Hooghly. By the 18th century the Portuguese presence had almost disappeared from Bengal. Portuguese settlements in Bengal Portuguese remains in Bengal • Now, in Bengal there are only a few physical vestiges of the Portuguese presence, a few churches and some ruins. But the Portuguese influence lives on Bengal in other ways— • Few descendents of Luso-Indians (descendants of the offspring of mixed unions between Portuguese and local women) and descendants of Christian converts are living in present Bengal. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Towards Food Sovereignty Reclaiming Autonomous Food Systems

Towards Food Sovereignty Reclaiming autonomous food systems Michel Pimbert Reclaiming Diversi TY & CiTizensHip Towards Food Sovereignty Reclaiming autonomous food systems Michel Pimbert Table of Contents Chapter 7. Transforming knowledge and ways of knowing ........................................................................................................................3 7.1. Introduction...............................................................................................................................................................................................3 7.2. Transforming knowledge..........................................................................................................................................................................6 7.2.1. Beyond reductionism and the neglect of dynamic complexity ..........................................................................................6 7.2.2. Overcoming myths about people and environment relations .........................................................................................10 7.2.3. Decolonising economics......................................................................................................................................................17 7.3. Transforming ways of knowing..............................................................................................................................................................22 7.3.1. Inventing more democratic ways of knowing...................................................................................................................22 -

Immigration and Identity Negotiation Within the Bangladeshi Immigrant Community in Toronto, Canada

IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Anthropology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder ii THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis to the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and to LAC’s agent (UMI/PROQUEST) to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. iii Dedicated to my dearest mother and father who showed me dreams and walked with me to face challenges to fulfill them. iv ABSTRACT IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA Bangladeshi Bengali migration to Canada is a response to globalization processes, and a strategy to face the post-independent social, political and economic insecurities in the homeland. -

And the English Imperative: a Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi

“Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi by Usree Bhattacharya A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Prof. Laura Sterponi, Chair Prof. Claire Kramsch Prof. Robin Lakoff Fall 2013 “Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi Copyright © 2013 By Usree Bhattacharya Abstract “Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi by Usree Bhattacharya Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Laura Sterponi, Chair This dissertation is a study of English language and literacy in the multilingual Indian context, unfolding along two analytic planes: the first examines institutional discourses about English learning across India and how they are motivated and informed by the dominant theme of “globalization,” and the second investigates how local language ideologies and literacy practices correspond to these discourses. An ethnographic case study, it spans across four years. The setting is a microcosm of India’s own complex multilingualism. The focal children speak Bengali or Bihari as a first language; Hindi as a second language; attend an English-medium village school; and participate daily in Sanskrit prayers. Within this context, I show how the institutional discursive framing of English as a prerequisite for socio- economic mobility, helps produce, reproduce, and exacerbate inequalities within the world’s second largest educational system. -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in the Sundarbans

Non-timber Forest Products and Livelihoods in the Sundarbans Fatima Tuz Zohora1 Abstract The Sundarbans is the largest single block of tidal halophytic mangrove forest in the world. The forest lies at the feet of the Ganges and is spread across areas of Bangladesh and West Bengal, India, forming the seaward fringe of the delta. In addition to its scenic beauty, the forest also contains a great variety of natural resources. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) play an important role in the livelihoods of local people in the Sundarbans. In this paper I investigate the livelihoods and harvesting practices of two groups of resource harvesters, the bauwalis and mouwalis. I argue that because NTFP harvesters in the Sundarbans are extremely poor, and face a variety of natural, social, and financial risks, government policy directed at managing the region's mangrove forest should take into consideration issues of livelihood. I conclude that because the Sundarbans is such a sensitive area in terms of human populations, extreme poverty, endangered species, and natural disasters, co-management for this site must take into account human as well as non-human elements. Finally, I offer several suggestions towards this end. Introduction A biological product that is harvested from a forested area is commonly termed a "non-timber forest product" (NTFP) (Shackleton and Shackleton 2004). The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines a non-timber forest product (labeled "non-wood forest product") as "A product of biological origin other than wood derived from forests, other wooded land and trees outside forests" (FAO 2006). For the purpose of this paper, NTFPs are identified as all forest plant and animal products except for timber. -

Dosti Greater Thane Brochure

THE CITY OF HAPPINESS CITY OF HAPPINESS Site Address: Dosti Greater Thane, Near SS Hospital, Kalher Junction 421 302. T: +91 86577 03367 Corp. Address: Adrika Developers Pvt. Ltd., Lawrence & Mayo House, 1st Floor, 276, Dr. D. N. Road, Fort, Mumbai - 400 001 • www.dostirealty.com Dosti Greater Thane - Phase 1 project is registered under MahaRERA No. P51700024923 and is available on website - https://maharerait.mahaonline.gov.in under registered projects Disclosures: (1) The artist’s impressions and stock image are used for representation purpose only. (2) Furniture, fittings and fixtures as shown/displayed in the show flat are for the purpose of showcasing only and do not form part of actual standard amenities to be provided in the flat. The flats offered for sale are unfurnished and all the amenities proposed to be provided in the flat shall be incorporated in the Agreement for Sale. (3) The plans are tentative in nature and proposed but not yet sanctioned. The plans, when sanctioned, may vary from the plans shown herein. (4) Dosti Club Novo is a Private Club House. It may not be ready and available for use and enjoyment along with the completion of Dosti Greater Thane - Phase 1 as its construction may get completed at a later date. The right to admission, use and enjoyment of all or any of the facilities/amenities in the Dosti Club Novo is reserved by the Promoters and shall be subject to payment of such admission fees, annual charges and compliance of terms and conditions as may be specified from time to time by the Promoters. -

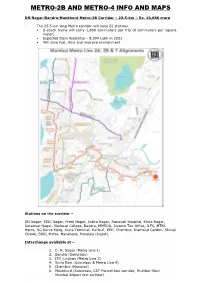

Metro-2B and Metro-4 Info and Maps

METRO-2B AND METRO-4 INFO AND MAPS DN Nagar-Bandra-Mankhurd Metro-2B Corridor – 23.5-km – Rs. 10,986 crore · The 23.5-km long Metro corridor will have 22 stations • 6-coach trains will carry 1,800 commuters per trip (8 commuters per square meter) • Expected Daily Ridership – 8.099 Lakh in 2021 • Will save fuel, time and improve environment Stations on the corridor – DN Nagar, ESIC Nagar, Prem Nagar, Indira Nagar, Nanavati Hospital, Khira Nagar, Saraswat Nagar, National College, Bandra, MMRDA, Income Tax Office, ILFS, MTNL Metro, SG Barve Marg, Kurla Terminal, Kurla-E, EEH, Chembur, Diamond Garden, Shivaji Chowk, BSNL Metro, Mankhurd, Mandala (Depot). Interchange available at – 1. D. N. Nagar (Metro Line 1) 2. Bandra (Suburban) 3. ITO junction (Metro Line 3) 4. Kurla East (Suburban & Metro Line 4) 5. Chembur (Monorail) 6. Mankhurd (Suburban, CST-Panvel fast corridor, Mumbai–Navi Mumbai Airport fast corridor) Wadala-Ghatkopar-Thane -Kasarvadavli Metro-4 corridor – 32-km – Rs. 14,549 crore • The 32.32-km long Metro corridor will have 32 stations • 6-coach trains will carry 1,800 commuters per trip (8 commuters per square meter) • Expected Daily Ridership – 8.7 Lakh in 2021-22 • Will save fuel, time and improve environment Stations on the Corridor – Wadala Depot, Bhakti Park Metro, Anik Nagar Bus Depot, Suman Nagar, Siddharth Colony, Amar Mahal Junction, Garodia Nagar, Pant Nagar, Laxmi Nagar, Shreyas Cinema, Godrej Company, Vikhroli Metro, Surya Nagar, Gandhi Nagar, Naval Housing, Bhandup Mahapalika, Bhandup Metro, Shangrila, Sonapur, Mulund Fire Sta tion, Mulund Naka, Teen Haath Naka (Thane), RTO Thane, Mahapalika Marg, Cadbury Junction, Majiwada, Kapurbawdi, Manpada, Tikuji -ni-wadi, Dongri Pada, Vijay Garden, Kasarvadavali with car depot at Owale . -

Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: the Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues

American Journal of www.biomedgrid.com Biomedical Science & Research ISSN: 2642-1747 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mini Review Copyright@ Abdul Kader Mohiuddin Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: The Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues Abdul Kader Mohiuddin* Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Bangladesh To Cite This Article: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin. Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: The Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2019 - 4(5). AJBSR.MS.ID.000829. DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.04.000829 Received: August 13, 2019 | Published: August 20, 2019 Abstract Personal care products and facial cosmetics are commonly used by millions of consumers on a daily basis. Direct application of cosmetics on human skin makes it vulnerable to a wide variety of ingredients. Despite the protecting role of skin against exogenous contaminants, some of the ingredients in cosmetic products are able to penetrate the skin and to produce systemic exposure. Consumers’ knowledge of the potential risks of the frequent application of cosmetic products should be improved. While regulations exist in most of the high-income countries, in low income countries of heavy metals are strict. There is a need for enforcement of existing rules, and rigorous assessment of the effectiveness of these regulations. The occurrencethere -

Questions and Answers on DEATH

Questions and Answers on DEATH. What is Go-dan? Go-dan? Go means the cow and dan means gift. So Go-dan is the giving the gift of a cow to a Brahmin. This is an extremely important prayer that one performs in one's life. When should Go-Daan puja be performed? Many people are under the impression that this prayer is only performed when one is about to die. This is a great misunderstanding. This prayer should be done when one is fit and in a healthy mind. When one performs this prayer when one is fit and healthy then its efficacy is increased 1000 fold, if a sick man makes the gift its efficacy is only a 100 fold. If his son gifts something on behalf of the dead, the gift is indirect and its efficacy is rendered as normal. (Garuda Purana Preta Kand Chapter 47 verses 37-38) What should be given in the Go-Daan puja? Sesame seed, iron, gold, cotton, salt, seven types of grains, earth and a cow. The dying person should give these 8 precious gifts to a brahmana. The wise have prescribed the gift of salt to be given freely and it opens the doorway to the other world. (Garuda Purana Preta Khanda chapter 4 verses 7-8,14) Why do Hindus perform cremation? In Hinduism, cremation is prescribed by our shastras and it is preferred means of disposal of the corpse. The others being disposing the body via water or burial. The most important reason for a cremation is that with the destruction of the body, the soul of the deceased, existing as the vaayuja shareera is no longer drawn to, or able to identify with the body.