Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 198

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications of Climate Change for Food-Caching Species

Demographic and Environmental Drivers of Canada Jay Population Dynamics in Algonquin Provincial Park, ON by Alex Odenbach Sutton A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Alex O. Sutton, April 2020 ABSTRACT Demographic and Environmental Drivers of Canada Jay Population Dynamics in Algonquin Provincial Park, ON Alex Sutton Advisor: University of Guelph, 2020 Ryan Norris Knowledge of the demographic and environmental drivers of population growth throughout the annual cycle is essential to understand ongoing population change and forecast future population trends. Resident species have developed a suite of behavioural and physiological adaptations that allow them to persist in seasonal environments. Food-caching is one widespread behavioural mechanism that involves the deferred consumption of a food item and special handling to conserve it for future use. However, once a food item is stored, it can be exposed to environmental conditions that can either degrade or preserve its quality. In this thesis, I combine a novel framework that identifies relevant environmental conditions that could cause cached food to degrade over time with detailed long-term demographic data collected for a food-caching passerine, the Canada jay (Perisoreus canadensis), in Algonquin Provincial Park, ON. In my first chapter, I develop a framework proposing that the degree of a caching species’ susceptibility to climate change depends primarily on the duration of storage and the perishability of food stored. I then summarize information from the field of food science to identify relevant climatic variables that could cause cached food to degrade. -

Red Tree Vole High Priority Site Management Recommendation

High-Priority Site Management Recommendations for the Red Tree Vole (Arborimus longicaudus) Version 1.0 April 2016 Photo by Nick Hatch Author Rob Huff is the conservation planning coordinator for the interagency special status and sensitive species program, USDI Oregon/Washington Bureau of Land Management and USDA Region 6 Forest Service, PO Box 2965, Portland, OR 97208. USDI Bureau of Land Management, Oregon USDI Bureau of Land Management, California USDA Forest Service Region 6 USDA Forest Service Region 5 Executive summary Management status The red tree vole (Arborimus longicaudus) is a small arboreal microtine that is endemic to the coniferous forests of western Oregon and northwestern California (Howell 1926, Maser 1966, Verts and Carraway 1998). Red tree voles are a category C survey and manage species under the Northwest Forest Plan (USDA and USDI 2001). As such, surveys are required for their nests prior to habitat-disturbing activities, but not all red tree vole sites require protection to provide for a reasonable assurance of species persistence. Sites needing protection to meet that persistence objective and sites not needing protection are called high-priority and non-high priority sites, respectively. Few attempts have been made to discriminate between high- and non-high priority sites; therefore most red tree vole sites are currently protected. The US Fish and Wildlife Service determined that listing the red tree vole as a distinct population segment north of the Siuslaw River in the Oregon Coast Ranges under the Endangered Species Act was warranted but precluded (USDI FWS 2011). The population segment was added to the USFWS candidate species list which triggered the inclusion of red tree voles within this geographic area to the BLM special status and Forest Service sensitive species lists. -

Natural History of Oregon Coast Mammals Chris Maser Bruce R

Forest Servile United States Depa~ment of the interior Bureau of Land Management General Technical Report PNW-133 September 1981 ser is a ~ildiife biologist, U.S. ~epa~rn e Interior, Bureau of La gement (stationed at Sciences Laboratory, Corvallis, Oregon. Science Center, ~ewpo Sciences Laborato~, Corvallis, Oregon. T. se is a soil scientist, U.S. wa t of culture, Forest Service, Pacific rthwest Forest and ange ~xperim Station, lnst~tute of orthern Forestry, Fairbanks, Alaska. Natural History of Oregon Coast Mammals Chris Maser Bruce R. Mate Jerry F. Franklin C. T. Dyrness Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-133 September 1981 Published in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management U.S. Department of the Interior Abstract Maser, Chris, Bruce R. Mate, Jerry F. Franklin, and C. T. Dyrness. 1981. Natural history of Oregon coast mammals. USDA For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-133, 496 p. Pac. Northwest For. and Range Exp. Stn., Portland, Oreg. The book presents detailed information on the biology, habitats, and life histories of the 96 species of mammals of the Oregon coast. Soils, geology, and vegetation are described and related to wildlife habitats for the 65 terrestrial and 31 marine species. The book is not simply an identification guide to the Oregon coast mammals but is a dynamic portrayal of their habits and habitats. Life histories are based on fieldwork and available literature. An extensive bibliography is included. Personal anecdotes of the authors provide entertaining reading. The book should be of use to students, educators, land-use planners, resource managers, wildlife biologists, and naturalists. -

WILDLIFE in a CHANGING WORLD an Analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™

WILDLIFE IN A CHANGING WORLD An analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ Edited by Jean-Christophe Vié, Craig Hilton-Taylor and Simon N. Stuart coberta.indd 1 07/07/2009 9:02:47 WILDLIFE IN A CHANGING WORLD An analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ first_pages.indd I 13/07/2009 11:27:01 first_pages.indd II 13/07/2009 11:27:07 WILDLIFE IN A CHANGING WORLD An analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ Edited by Jean-Christophe Vié, Craig Hilton-Taylor and Simon N. Stuart first_pages.indd III 13/07/2009 11:27:07 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily refl ect those of IUCN. This publication has been made possible in part by funding from the French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Red List logo: © 2008 Copyright: © 2009 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Vié, J.-C., Hilton-Taylor, C. -

(Arborimus Longicaudus), Sonoma Tree Vole (A. Pomo), and White-Footed Vole (A

United States Department of Agriculture Annotated Bibliography of the Red Tree Vole (Arborimus longicaudus), Sonoma Tree Vole (A. pomo), and White-Footed Vole (A. albipes) Forest Pacific Northwest General Technical Report August Service Research Station PNW-GTR-909 2016 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all pro- grams). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimi- nation Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/com- plaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Distribution and Abundance of Red Tree Voles in Oregon Based on Occurrence in Pellets of Northern Spotted Owls

Eric D. Forsman, U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Robert G. Anthony, Oregon Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 and Cynthia J. Zabel, U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Arcata, California 95521 Distribution and Abundance of Red Tree Voles in Oregon Based on Occurrence in Pellets of Northern Spotted Owls Abstract Red tree voles are one of the least understood small mammals in the Pacific Northwest, because they live in the forest canopy and are difficult to sample using conventional trapping methods. We examined the distribution and relative abundance of tree voles in different regions of Oregon based on their occurrence in diets of northern spotted owls. We identified the skeletal remains of 2,954 red tree voles in regurgitated pellets collected from 1,118 different spotted owl territories. Tree voles were found in the diet at 486 territories. They were most common in the diet in the central and south coastal regions, where average owl diets included 13% and 18% tree voles. They were absent from owl diets on the east slope of the Cascades and in most of the area east of Grants Pass and south of the Rogue River. Our data were sparse from the northern Coast Ranges and northern Cascades, but suggested comparatively low numbers of voles in those regions. The proportion of tree voles in the diet was negatively correlated with elevation in the Cascades, where tree voles were common in the diet at elevations < 975 m, and rare in the diet at elevations > 1,220 m. -

Red Tree Vole

SURVEY PROTOCOL FOR THE RED TREE VOLE Arborimus longicaudus (= Phenacomys longicaudus in the Record of Decision of the Northwest Forest Plan) Version 2.0 By Brian Biswell Mike Blow Laura Finley Sarah Madsen Kristin Schmidt TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................1 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................3 Definitions..................................................................3 Taxonomic/Nomenclatural History...............................................4 Geographic Range ...........................................................5 Biology and Habitat Requirements...............................................6 Biology...................................................................6 Home Range/Dispersal ......................................................7 Abundance ................................................................7 Habitat...................................................................8 Nests.....................................................................9 SURVEY PROTOCOL ........................................................9 Protocol Objectives...........................................................9 Implementation of Protocol ....................................................9 Trigger for Protocol Surveys...................................................10 Survey Methodology .........................................................10 Line Transect Survey Method ................................................11 -

Appendix C Wildlife Supplement

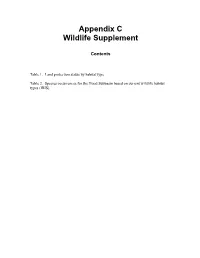

Appendix C Wildlife Supplement Contents Table 1. Land protection status by habitat type Table 2. Species occurrences for the Hood Subbasin based on current wildlife habitat types (IBIS) Table 1. Land Protection Status by habitat type using GIS data layers provided by the Northwest Habitat Institute for the subbasin planning effort. Total Acres subject to discrepancies in input data layers. Metadata link is at www.nwhi.org/ibis/mapping/gisdata/docs/crb/crb_lsstatus_meta.htm. Analysis Area Habitat Protection Status Acres Columbia River Tributaries 63022 Agriculture, pasture and mixed environs 2382 Low 6 Medium 4 None 2372 Montane mixed conifer forest 3653 High 813 Low 2660 Medium 89 None 91 Open water - lakes, rivers, streams 152 High 48 Low 43 Medium 26 None 35 Ponderosa pine forest and woodlands 2 High 2 Urban and mixed environs 1280 Low 126 None 1154 Westside lowlands conifer-hardwood forest 55553 High 31236 Low 17977 Medium 1226 None 5114 Hood River Basin 217492 Agriculture, pasture and mixed environs 33400 Low 152 None 33248 Alpine grassland and shrublands 4469 High 3386 Low 1083 Eastside (interior) grasslands 1538 Low 169 None 1369 Eastside (interior) mixed conifer forest 23194 Low 8252 None 14942 Herbaceous wetlands 197 High 56 Low 141 Montane coniferous wetlands 116 Low 99 None 16 Montane mixed conifer forest 47895 High 14560 Low 33061 None 274 Open water - lakes, rivers, streams 523 High 250 Low 217 None 55 Ponderosa pine forest and woodlands 4739 High 13 Low 1341 None 3385 Subalpine parkland 4394 High 2883 Low 1511 Urban and mixed environs 763 None 763 Westside lowlands conifer-hardwood forest 95388 High 2357 Low 51835 None 41196 Westside oak and dry Douglas-fir forest and woo 876 Low 240 None 636 Subbasin Species Occurrences Generated by IBIS on 10/21/2003 11:09:13 AM. -

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Welcome to Tualatin River National Wildlife Tualatin River Refuge means different tilings to NWR different creatures. For some it's a place where they raise their young. and others just a stopover during migration. It's also a place that some only spend the winter, and to ethers, it is a year-round home. Established in 1992, the Refuge is located within the floodplain of the Tualatin River basin near Sherwood, Oregon. Refuge habitats are varied and include rivers and streams, seasonal and forested wetlands, riparian areas, grasslands, and forested uplands. An important breeding area for neotropical migratory songbirds, the Refuge also supports a significant breeding population of wood ducks and hooded mergansers. There is something to experience in every season. From thousands of waterfowl in the winter to breeding songbirds in summer, the Refuge is ever changing. Enjoying the Wo encourage you to explore the Refuge's beauty of this area and stop, look, and Wildlife listen to the abundant wildlife that call it home. The Refuge is a place where wildlife comes first so think of yourself as a visitor to their home. You will be a more successful wildlife observer if you: move slowly, talk softly, use binoculars, and leave only footprints behind. The wildlife species in this brochure have been grouped into four categories: birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles. Red-tailed hawks nni be seen (mil heard soaring the open spaces over the Refuge Enjoying the Numbers and species of birds you Seasons Sp - Spring, March through May Refuge's will see here varies according to S - Summer, June through August Birdlife season, with the greatest numbers F - Fall, September through present from October to May. -

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Control Operator Training Manual Revised March 31, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 Page # Introduction 5 Wildlife “Damage” and Wildlife “Nuisance” 5 Part 2 History 8 Definitions 9 Rules and Regulations 11 Part 3 Business Practices 13 Part 4 Methods of Control 15 Relocation of Wildlife 16 Handling of Sick or Injured Wildlife 17 Wildlife That Has Injured a Person 17 Euthanasia 18 Transportation 19 Disposal of Wildlife 20 Migratory Birds 20 Diseases (transmission, symptoms, human health) 20 Part 5 Liabilities 26 Record Keeping and Reporting Requirements 26 Live Animals and Sale of Animals 26 Complaints 27 Cancellation or Non-Renewal of Permit 27 Part 6 Best Management Practices 29 Traps 30 Bodygrip Traps 30 Foothold Traps 30 Box Traps 31 Snares 31 Specialty Traps 32 Trap Sets 33 Bait and Lures 33 Equipment 33 Trap Maintenance and Safety 34 Releasing Nontarget Wildlife 34 2 Resources 36 Part 7 Species: Bats 38 Beaver 47 Coyote 49 Eastern Cottontail 52 Eastern Gray Squirrel 54 Eastern Fox Squirrel 56 Western (Silver) Gray Squirrel 58 Gray Fox 60 Red Fox 62 Mountain Beaver 64 Muskrat 66 Nutria 68 Opossum 70 Porcupine 72 Raccoon 74 Striped Skunk 77 Oregon Species List 79 Part 8 Acknowledgements 83 References and Resources 83 3 Part 1 Introduction Wildlife “Damage” and Wildlife “ Nuisance” 4 Introduction As Oregon becomes more urbanized, wildlife control operators are playing an increasingly important role in wildlife management. The continued development and urbanization of forest and farmlands is increasing the chance for conflicts between humans and wildlife. -

Nederlandse Namen Van De Overige Knaagdieren, Waaronder Alle Muizen

Blad1 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P 1 Klasse Orde Suborde Superfamilie Familie Subfamilie Tak Geslacht Soort Ondersoort Betekenis Engels Frans Duits Spaans Nederlands 2 Mammalia met melkklier Mammals Mammifères Säugetiere Mamiféros Zoogdieren 3 Rodentia knagers Rodents Rongeurs Nagetiere Roedores Knaagdieren 4 Myomorpha muis + vorm Mouse-like rodents Myomorphs Mauseverwandten Miomorfos Muisachtigen 5 Dipodoidea tweepoot + idea Jerboa-like rodents Berken-, Huppel- & Springmuizen 6 Sminthidae Grieks sminthos = muis + idae Birch mice Berkenmuizen 7 Sicista Berkenmuizen 8 S. caudata met staart Long-tailed birch mouseSiciste à longue queue Langschwanzbirkenmaus Ratón listado de cola largo Langstaartberkenmuis 9 S. concolor eenkleurig Chinese birch mouse Siciste de Chine China-Birkenmaus Ratón listado de China Chinese berkenmuis 10 S.c. concolor eenkleurig Gansu birch mouse Gansuberkenmuis 11 S.c. leathemi Leathem ??? Kashmir birch mouse Kasjmirberkenmuis 12 S.c. weigoldi Hugo Weigold Sichuan birch mouse Sichuanberkenmuis 13 S. tianshanica Tiensjangebergte, Azië Tian Shan birch mouse Siciste du Tian Shan Tienschan-BirkenmausRatón listado de Tien Shan Tiensjanberkenmuis 14 S. caucasica Kaukassisch Caucasian birch mouse Siciste du Caucase Kaukasus-BirkenmausRatón listado del Cáucaso Kaukasusberkenmuis 15 S. kluchorica Klukhorrivier, Kaukasus Kluchor birch mouse Siciste du Klukhor Kluchor-Birkenmaus Ratón listado de Kluchor Klukhorberkenmuis 16 S. kazbegica Kazbegi-district, Georgië Kazbeg birch mouse Siciste du Kazbegi Kazbeg-BirkenmausRatón listado de Kazbegi Kazbekberkenmuis 17 S. armenica Armeens Armenian birch mouseSiciste d'Arménie Armenien-Birkenmaus Ratón listado de Armenia Armeense berkenmuis 18 S. napaea een weidenimf Altai birch mouseSiciste de l'Altaï Nördliche Altai-Birkenmaus Ratón listado de Altái Altaiberkenmuis 19 S.n. -

Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska State Museum 3-7-1975 Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico J. Knox Jones Jr. Texas Tech University Dilford C. Carter Texas Tech University Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Zoology Commons Jones, J. Knox Jr.; Carter, Dilford C.; and Genoways, Hugh H., "Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico" (1975). Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum. 205. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Copyright 1975, Texas Tech University. Used by permission. OCCASIONAL PAPERS THE MUSEUM TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY NUMBER 28 7 MARCH 1975 REVISED CHECKLIST OF NORTH AMERICAN MAMMALS NORTH OF MEXICO J. KNOX JONES, JR., DILFORD C. CARTER, AND HUGH H. GENOWAYS Faunal checklists provide useful ready references for many kinds of endeavors, both in the laboratory and in the field, and are particularly helpful to students. Since publication two years ago of our "Checklist of North American mammals north of Mexico" (Jones et al., 1973), demand for that list has exceeded the supply set aside for general dis tribution; additionally, published systematic studies in the interval necessitate several changes in the list.