“What Font Should I Use?”: Five Principles for Choosing and Using Typefaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

SY*T*K Ffiptrxt&

SY*T*K ffiPTRXT& POEMS BY Swsan Elizabeth Howe STONtr SPIRITS Redd Center Publications Stone Spirits W Swsan Elizabeth Howe The Charles Redd Center for Western Studies Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 1997 Charles Redd Publications are made possible Hy a grant from Charles Redd. This grant served as the basis for the establishment of the Charles Redd Cenier for Western Studies at Brigham Young University. Center editor: William A. Wilson Cowr photograph courtesy of Aaron Coldenberg lWild Earth Images LiBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Howe, Susan, r949- Stone spirits / Susan trlizabeth Howe. {, p. cm. - (Redd Center publications) rseN r-56o85 -rc7-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Title. II. Series. rs3558.o8935s76 ry97 8n'.54-oczr 97-4874 cIP @ry97 by Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, Brigham Young Universif'. A11 rights reserved. First printing, r997. Printed in the United States of America. Distributed by Signature Books, 564 West 4oo North, Salt Lake City, Utah 84116 Author's acknowledgments appear on page 70. FOR MY PARENTS, Maralyne Haskell Howe and Elliot Castleton Howe Table of Contents Foreword, by Edward A. Ceary ix I. THE WORLD IS HARSH, NOT OF YOUR MAKING Things in the Night Sky 4 ArchAngel 5 The Wisdom of the Pyrotechnician 7 Flying at Night g Feeding rl Alternatives to Winter ry The Paleontologist with an Ear Infection ry Tiger trating a European 6 NorAm I Who I Was Then t7 t Lessons of Erosion rB II. THE BLUES OUT THERE Mountains Behind Her 20 Summer Days, A Painting by Georgia O'Keeffe 22 The Stolen Television Set 23 In the Cemetery, Studying Embryos 24 To the Maker of These Petroglyphs z6 Another Autumn zB Sexual Evolution 30 We Live in the Roadside Motel 32 lviil III. -

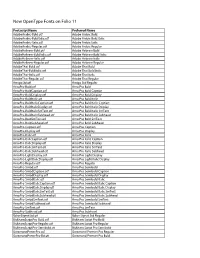

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Typeface Classification Serif Or Sans Serif?

Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Serif or Sans Serif? ABCDEFG ABCDEFG abcdefgo abcdefgo Adobe Jenson DIN Pro Book Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Typeface or font? ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Regular ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Italic TYPEFACE FAMILY ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold Italic Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Timeline Blackletter Humanist Old Style Transitional Modern Bauhaus Digital (aka Venetian) sans serif 1450 1460- 1716- 1700- 1780- 1920- 1980-present 1470 1728 1775 1880 1960 Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The model for the first movable types was Blackletter (also know as Block, Gothic, Fraktur or Old English), a heavy, dark, at times almost illegible — to modern eyes — script that was common during the Middle Ages. from I Love Typography http://ilovetypography.com/2007/11/06/type-terminology-humanist-2/ Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Types based on blackletter were soon superseded by something a little easier Humanist (also refered to Venetian).. ABCDEFG ABCDEFG > abcdefg abcdefg Adobe Jenson Fette Fraktur Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The Humanist types (sometimes referred to as Venetian) appeared during the 1460s and 1470s, and were modelled not on the dark gothic scripts like textura, but on the lighter, more open forms of the Italian humanist writers. The Humanist types were at the same time the first roman types. Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Characteristics 1. -

Linotype Matrix 4.2—The Legend Continues

Mergenthaler Edition releases second issue of the new Linotype Matrix Linotype Matrix 4.2—the legend continues. Bad Homburg, 16 May 2006. Following its highly successful relaunch of Linotype Matrix in magazine format last year, Linotype’s publishing label, Mergenthaler Edition, is now releasing the second issue of the classic typographic journal. Linotype Matrix Issue 4.2 takes an exciting and informative look at typography in history – with a thematic focus on the great 20th century type designer William Addison Dwiggins. Within the 64 pages of this richly illustrated issue readers will find articles contributed by some of the best talents working in typography today. For instance, writer and typographer John D. Berry explores the legacy of the Deberny & Peignot type foundry, while the article on Dwiggins’ life and work has been penned by type designer and scholar Paul Shaw, an established Dwiggins authority. Additionally, renowned type historian Sylvia Werfel takes a look at how type systems make designing texts easier. 2006 marks the 50th anniversary of W. A. Dwiggins’ death—an appropriate moment to look back at the contributions of one of the first truly significant type designers from the U.S. As Paul Shaw is currently working on a doctoral dissertation at Columbia University about Dwiggins, he is able to offer an in- depth look at his prolific career as an illustrator, and tells us how, in his late forties, he began a second remarkable career in typeface design at Linotype. Dwiggins was, in fact, the first major type designer to work for the Mergenthaler Linotype Co. in New York and was responsible for creating many great designs, including Metro and Electra, and his most enduring typeface, Caledonia. -

Design & Communications Style Guide

DESIGN & COMMUNICATIONS STYLE GUIDE v 1.0 2 INTRODUCTION 3 CREATIVE MESSAGING 32 CONTENTS The story 4 The creative message 33 Why experience matters 5 Creative messaging & structure 34 The macro approach 7 Brand mantra 9 AUDIENCE PROFILES 35 Keywords 11 Introduction 36 Audience 1: Nature lovers 37 LOGO 13 Audience 2: Memory makers 38 The logo 14 Audience 3: Mellow vacationers 39 Clear space & minimum size 15 Audience 4: Knowledge seekers 40 Logo suite 16 Audience 5: New Canadians 41 Incorrect logo usage 18 ETB and the County logo 19 EXECUTABLES 42 ETB and the County star 20 Banner stands 43 Advertorial 44 TYPOGRAPHY 21 Truck 45 Font 22 Envelope 46 Text styles 23 Table cloth 47 Adventure Passport 48 COLOUR 25 Website 49 Palette 26 GRAPHIC ELEMENTS 27 Photography 28 Framing 29 Camo 30 Icons 31 3 154 WORDS ONE STORY 4 Explore The Bruce (ETB) is our visitor invitation. layered limestone that is 4,000 years old. Even our 45.oºN 81.3oºW is our planetary street address. And tarts are unique – if we describe them as jammed with this unique expression of location sets the stage; the strawberries picked fresh four minutes away. We don’t reward of every visit should be an equally unique use any old pails for beach castles – we use three-litre experience. You can find rivers anywhere – ours are pails to make the best turrets. You don’t just scuba dive home to 30,000 steelheads. Our bike trails often cover in clear water here – you explore 18 shipwrecks. The point is simple: Curiosity fuels exploration. -

Typo Eina 01

Disseny de publicacions modulars Fixació del text + Tria i cànon tipogràfic Infografia Treball teòric Aquesta assignatura, juntament amb la de La fixació del text tracta del que es coneix com a Introducció i panoràmica de les tècniques de Es tracta d’una recerca relacionada amb el món Disseny de publicacions per contingut, són les composició del text (typesetting), que en trets generals la infografia en sessions breus on s’avaluen els tipogràfic. La història, la tècnica, els protagonistes… dues grans assignatures pràctiques d’aquesta engloba totes les operacions que es realitzen a recursos que aquest llenguatge periodístic aporta. Una aportació al coneixement general de la segona part del curs. El disseny de publicacions l’interior de les caixes de text en qualsevol publicació. tipografia en forma de treball autònom de modulars contempla la pràctica del disseny Per la seva banda, la tria tipogràfica és un recull Planificació de publicacions l’alumne i tutoritzada per professors del curs. de pàgina des de la perspectiva d’un sistema raonat i cronològic d’aquelles lletres que hauríem Taller pràctic de conceptualització de publicacions. Al final del procés, el treball es valorat jerarquitzat i flexible que s’adapta infinitament de coneixer i com es poden fer servir. S’avaluen tots els formats analògics i digitals per un comité d’avaluació. als contiguts, com es ara el disseny d’un diari. actuals i es desenvolupa un projecte curt. Disseny de publicacions per contingut Història de la pàgina + tendècies formals La manera alternativa de plantejar el disseny de Direcció d’art L’objectiu d’aquestes dues assignatures és per una pàgina, en contrast amb el disseny modular, és En aquest taller s’analitzen les possibilitats i les maneres banda conèixer els diferents sistemes de configuració la creació d’un sistema que permeti prioritzar de fer encàrrecs a tercers (il·lustradors, fotògrafs, de pàgina que han portat els sistemes simètrics les imatges i adaptar els textos amb voluntat tipògrafs…). -

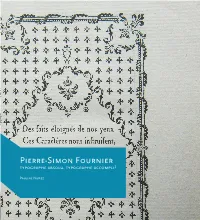

Pierre-Simon Fournier Typographe Absolu, Typographe Accompli?

Pierre-Simon Fournier typographe absolu, typographe accompli? Pauline Nuñez ¶ • °≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠° ≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°± Pierre-Simon Fournier * typographe absolu typographe accompli ? ≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°± °≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠°≠° • ¶ Racines 04 Éléments biographiques Éléments de style Œuvre 18 Le Manuel Typographique Utile aux gens de lettres : vision encyclopédiste de l’art typographique ? Fournier réformateur et innovateur Fournier ornementaliste baroque Quelques exemples de caractères baroques en Europe. Fournier créateur plagié Après Fournier 52 Les admirateurs, les « continuateurs » Le revival Fournier chez Monotype Que reste-t-il de Fournier aujourd’hui ? Repères bibliographiques 72 Rue des Sept-Voies, aujourd’hui rue Valette. Atget, 1925. racines Jean Claude Fournier anne-Catherine Guyou (Auxerre, ? – ?, 1729) († le 13 avril 1772) un Fils1 imprimeur à Auxerre Jean-pierre l’aîné Charlotte Madeleine piChault pierre siMon le jeune Marie Madeleine Couret de VilleneuVe (Paris, 1706 – Mongé, 1783) († l1764) (Paris, 15 sept. 1712 – Paris, le 8 oct. 1768) († le 3 avril 1775) Jean François fils Marie elizabeth Gando trois filles antoine siMon pierre2 MarGurite anne de beaulieu († le 27 nov. 1786) elizabeth Françoise (13 sept. 1759 – ?) (14 août 1750 – ?) († le 10 oct. 1786) Marie Marie anne bruant adélaïde († le 5 sept. 1788) sophie (?) a. F. MoMoro un Fils, beaulieu-Fournier une Fille (guillotiné en 1794) un Fils qui prît plus tard le nom de Fournier 1. Probablement nommé François. Jean Claude Fournier, imprimeur à Saint-Dizier 1775 – 1791, est peut-être son fils. 2. Parfois appelé «le jeune».Fournier, imprimeur à Saint-Dizier 1775 – 1791, est peut-être son fils. Éléments biographiques. Pierre-Simon Fournier naît le 15 septembre 112 à Paris au sein d’une famille déjà ancrée dans le monde de l’imprimerie. -

Type Anatomy

Typography Anatomy & Classification • Gregory V. Eckler Type Anatomy Beak: a single-sided upper serif Counter: a partially or fully enclosed space in a letter Upper lobe } Cap Height Spine Waist Baseline Throat } Lower lobe Spur Bowl: a curved stroke that creates an enclosed space Leg Tail: a finishing stroke at or below the baseline Serif Apex Arms Diagonals Crossbar Stem Vertex Typography Anatomy & Classification • Gregory V. Eckler Type Anatomy Terminal: finishing element to a stroke Point Size Cap Height Dot or Tittle Ascender Ear Shoulder Eye Spur } Shoulder X-Height Serif Link Finial Bowl Spur Descender Baseline Tail Loop { Hook Terminal Sheared Terminal Diagonals Leg Tail Tail Terminal Ligatures: two or more letters joined together Swash: A swash is a for practical or aesthetic reasons. flourish that replaces a terminal or serif. Typography Anatomy & Classification • Gregory V. Eckler Type Classification Fractur Sabon Baskerville Bodoni Pre-Venetian or Ancient Humanist or Venetian Transitional Didone or Modern Includes typefaces of Incised, Antique The roman typefaces of the 15th and These typefaces have sharper serifs These typefaces have thin, and Blackletter styles. 16th centuries emulated classical and a more vertical axis than Humanist staight serifs; vertical axis; and caligraphy letters. a sharp contrast in the strokes. Futura Helvetica Clarendon Gill Sans Egyptian or Slab Serif Humanist Sans Serif Transitional Sans Serif Geometeric Sans Serif Numerous bold and decorative A sans serif typeface where variations A uniform, upright character makes it Sans serif types built around typefaces introduced in the 19th century in line weight and terminal endings are similar to transitional serif letters. -

TRACING ARCHER ARTG106TRACING TYPOGRAPHYARCHER Spring 2017 ARTG106 TYPOGRAPHY Rosemary Rae Email: [email protected] Spring 2017

MiraCosta College / oceanside MAT 155 Graphic Design 2 : Typography TRACINGMin Choi // Fall 2017 ARCHER TRACING ARCHER ARTG106TRACING TYPOGRAPHYARCHER Spring 2017 ARTG106 TYPOGRAPHY Rosemary Rae email: [email protected] Spring 2017 Rosemary Rae email: [email protected] INFO ABOUT ARCHERINFO ABOUT ARCHER Archer is a slab serifArcher typeface is designeda slab serif in 2001 typeface by Tobias designed Frere-Jones in 2001 and Jonathanby Tobias Hoefler Frere-Jones for use in and Martha Jonathan Stewart HoeflerLiving magazine. for It was later released by Hoefler & Frere-Jones for commercial licensing. The typeface is a geometric or neo-grotesque slab serif, one with a geometric designuse in similar Martha to sans-serif Stewart fonts. Living It takes magazine. inspiration It was from later mid-twentieth released century by Hoefler designs & suchFrere-Jones as Rockwell. for The face is unique for combining the geometric structure of twentieth-century European slab-serifs but imbuing the face with a domestic, less strident tone of voice.commercial Balls were addedlicensing. to the The upper typeface terminals is on a geometricletters such asor C neo-grotesque and G to increase slab its charm. serif, oneItalics with are truea italic designs, with flourishesgeometric influenced design by calligraphy,similar to ansans-serif unusual feature fonts. for It takesgeometric inspiration slab serif fromdesigns. mid-twentieth As with many Hoeflercentury & Frere- INFO ABOUT ARCHER Jones designs, it was released in a wide range of weights from hairline to bold, reflecting its design goal as a typeface for complex Sweet but not saccharine, earnestmagazines. designs such as Rockwell. The face is unique for combining the geometric structure of twentieth- Archer is a slab serif typeface designed in 2001 by Tobias Frere-Jones and Jonathan Hoefler for but not grave, Archer is designed century European slab-serifs but imbuing the face with a domestic, less strident tone of voice. -

Electronic 2000 Magazine

AaBbCcDdEeFfGgHhliJjKkL1MmNnOo Pp I RrSsTtUuVvWwXxYyZz12345678908dECE$$0£.%!?00 UPPER AND LOWER CASE. THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TYPE AND. GRAPHIC DESIGN WINTER 1992. $5.00 U.S. $9.90 AUD Age The Electronic 2000 Magazine THE ALPHABET ACCORDING TO PRECISION TYPE ET A is• ff or AARDVARK4,frn,m,,o,,„Bureau / I' 0 ThEFEIS HOKE DEED % B is for Boy t m r y ra The Complete Font Software Resourte 10',1 -71%i-- Reference Guide C is for Columbus Version 0 56.95 4;07c'rc i D is for Bill's,,Trations ""'"Pe from U Design Type found ,/ ■tita An thin E is for [111 at A F is for Flyer '\ Gis for Game Pi JA A H is for llotElllodErn( from Treacyfaces GuitELIKE It I is for 117LstroEt om inotyp THE PRECISION TYPE REFERENCE GUIDE VERSION 4.0 J is for JUNIPER N trom Adobe 0 K is for Ir5 r f P T-Lfrom ,,,,E,,,,,,e,‘ AMAZING! INUEDIBLE! L is for 1.4 no;i It's one of the largest and most . /10 togEs of fonts, 1p H, H A informative font resources ever M is for SBI Ivoun IFIF published! Thousands of fonts Nis for Normande from the Major Type Libraries hem 13,tstrearn (11-11011s, SoftworE Ois for Oz Brush plus Designer foundries and from A', Alphabets Inc Specialty (ollections. P is for Pelican The Precision Type Reference Tools 0 much more., ()is for 1). F TIIMA Guide also features (D-ROM Isom Fetraset Type Libraries, font Software R is for Meg [Hp yts Np Applications & Tools, font (4,'S All for onlg SOU (11111', Products for HP Printers, S is for 9 THE $6.95 COST OF THE REFERENCE GUIDE IS 5(01,0,r_ rye Typographic Reference Books FULLY REFUNDED WITH YOUR FIRST ORDER FROM PRECISION TYPE.