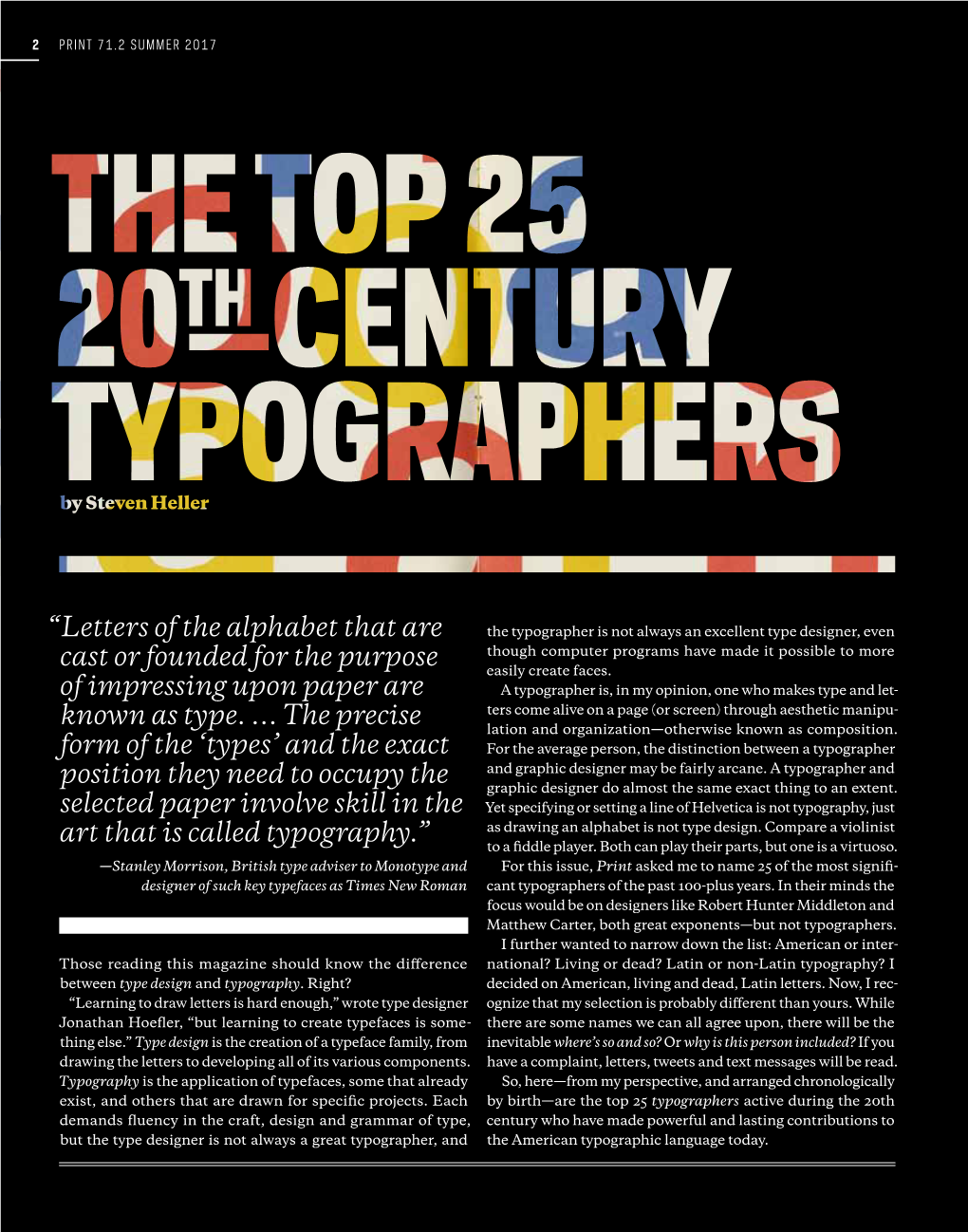

The Top 25 20Th Century Typographers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

No. 25 a Secret Index—

a secret index— division leap no. 25 a secret index— Booksellers, publishers and researchers of the history of print culture. Collections purchased. Books found. Appraisals performed. Libraries built. divisionleap.com no. 25 83. 35. 59. 39. 39. 27. 30. 25. 21. 65. 48. 72. 6. contents a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 b. Reproduction—Computing—Classification—Architecture 23 c. The Body—Tattooing—Incarceration—Crime—Sexuality 33 d. Social Movements—1968—Feminism—The SI & After 47 e. Music 57 f. Literature—Poetry—Periodicals 63 g. Film—Chris Marker 77 h. Art 85 i. Punk Zines 91 Additional images of all items available at divisionleap.com or by request. a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 2. 1. 18 a. The Birth of Walter Benjamin’s Theory Heuber so messianically feels is near … ” of the Messianic McCole, analyzing this same letter, notes that this appears to be Benjamin’s first use of the term 1. [Victor Hueber] Die Organisierung der “Messianic” in his writings [McCole, p. 61]. The Intelligenz. Ein Aufruf. Zweite, erweiterte Auflage. idea would haunt Benjamin’s subsequent works Als Manuskript gedruckt. on history, and reach its conclusion in the second [Prague]: Druck H. Mercy, [1910]. 8vo, thesis in On the Concept of History, written just 107 pp, stab-stapled and glue bound into violet before his march into the mountains. “The past printed wraps. Front and back panels of wraps carries with it a secret index, by which it is referred detached but present, with the paper covering to its resurrection. There is an agreement and an the spine mostly perished. -

A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 11-1-1992 A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P. Wall Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Wall, David P., "A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology" (1992). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School ofPrinting Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to Certify that the Master's Thesis of David P. Wall With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master ofScience degree at the convocation of DECEMBER 1992 Da,e Thesis Committee: David Pankow Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Program Coordinator George H. Ryan Direcmr or Designa[e A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology by David P. Wall A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology November 1992 Project Advisor: Professor David Pankow Introduction type,' When Adobe Systems introduced in 1990 their first digital library of 'wood the event marked the latest step forward in a tradition dating back to 1828, when Darius Wells, ofNew Wells' York City, perfected the equipment and techniques needed to mass produce wood type. -

Tracing Futura

MiraCosta College / oceanside MAT 155 Graphic Design 2 : Typography Min Choi // Fall 2017 TRACING FUTURA FUTURA— the prototype of the family of geometric sans-serif typefaces. It was designed in 1927 by Paul Renner. As opposed to earlier sans-serif designs, the strokes appear to be even weight and geometric. This seems most visible in the almost perfectly round stroke of the O but Futura is actually slightly imperfect. It is often said that Futura was directly related to the Bauhaus. Renner him- self was not associated with the Bauhaus although many of the modern principles taught at the Bauhaus are incorporated into the letterform design of Futura. Futura was developed during a competitive period in the 1920s when various foundries were developing modern san serif type faces for various lead type setting technology. It would be followed by Gill Sans by U.K. Monotype designed by Eric Gill and Metro by U.S. Linotype designed by W. A. Dwiggins. Futura was one of the most popular fonts in use in the 20th century, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, and is in use in the corporate Roman- design of Volkswagen to this day. (See classic ad at left). Check out more of Volkswagen’s iconic print advertising: http://fontsinuse. The basic letterform style so com/uses/1976/volkswagen-of-america-ads-1960-66 called because it is derived from inscriptions on Roman Futura remains an important typeface family and is used world wide on a daily basis for print and digital purposes as both a headline monuments. and text font. -

SY*T*K Ffiptrxt&

SY*T*K ffiPTRXT& POEMS BY Swsan Elizabeth Howe STONtr SPIRITS Redd Center Publications Stone Spirits W Swsan Elizabeth Howe The Charles Redd Center for Western Studies Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 1997 Charles Redd Publications are made possible Hy a grant from Charles Redd. This grant served as the basis for the establishment of the Charles Redd Cenier for Western Studies at Brigham Young University. Center editor: William A. Wilson Cowr photograph courtesy of Aaron Coldenberg lWild Earth Images LiBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Howe, Susan, r949- Stone spirits / Susan trlizabeth Howe. {, p. cm. - (Redd Center publications) rseN r-56o85 -rc7-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Title. II. Series. rs3558.o8935s76 ry97 8n'.54-oczr 97-4874 cIP @ry97 by Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, Brigham Young Universif'. A11 rights reserved. First printing, r997. Printed in the United States of America. Distributed by Signature Books, 564 West 4oo North, Salt Lake City, Utah 84116 Author's acknowledgments appear on page 70. FOR MY PARENTS, Maralyne Haskell Howe and Elliot Castleton Howe Table of Contents Foreword, by Edward A. Ceary ix I. THE WORLD IS HARSH, NOT OF YOUR MAKING Things in the Night Sky 4 ArchAngel 5 The Wisdom of the Pyrotechnician 7 Flying at Night g Feeding rl Alternatives to Winter ry The Paleontologist with an Ear Infection ry Tiger trating a European 6 NorAm I Who I Was Then t7 t Lessons of Erosion rB II. THE BLUES OUT THERE Mountains Behind Her 20 Summer Days, A Painting by Georgia O'Keeffe 22 The Stolen Television Set 23 In the Cemetery, Studying Embryos 24 To the Maker of These Petroglyphs z6 Another Autumn zB Sexual Evolution 30 We Live in the Roadside Motel 32 lviil III. -

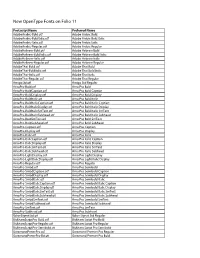

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

AVENIR Family

An Introduction To The AVENIR Family By Stacey Chen O V E R V I E W l Avenir was designed by Adrian Frutiger. l The typeface was first released in 1988 with three weights, before being expanded to six weights. l In 2004, together with Akira Kobayashi, Frutiger reworked the Avenir family. l Avenir has now become a common font in web, print, and graphic design, etc. l Frutiger was born in Unterseen, Switzerland 1928. l At age 16, Frutiger was apprenticed as a compositor to a printer, while taking classes in woodcuts and drawing. l With his second wife, Frutiger had two daughters, who both experienced mental health problems and committed suicide as adolescents. l Frutiger spent most of his professional career working in Paris and living in France, returning to Switzerland later in life. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R l Charles Peignot of Deberny Et Peignot recruited Frutiger based on the quality of the wood- engraved illustrations of his essay. l Impressed by the success of Futura typeface, Peignot encouraged a new, geometric sans-serif type in competition. l Frutiger disliked the regimentation of Futura, and persuaded Peignot that the new sans-serif be based on the realist model. l In 1988, Frutiger completed the family Avenir. Frutiger intended the font to be a more human version of geometric sans-serif types popular in the 1930s, such as Erbar and Futura. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R “Avenir” = “Future” French English A V E N I R i s l Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed in 1927 by Paul Renner. -

Revisiting the So-Called “Legibility Wars” of the '80S and '

58 PRINT 70.3 FALL 2016 PRINTMAG.COM 59 HAT DID YOU DO during the Legibility Wars?” asked one of my more inquisitive design history students. “Well, it wasn’t actually a war,” I said, recalling the period during the mid-’80s through the mid- to late-’90s when there were stark divisions “Wbetween new and old design generations—the young anti- Modernists, and the established followers of Modernism. “It was rather a skirmish between a bunch of young designers, like your age now, who were called New Wave, Postmodern, Swiss Punk, whatever, and believed it necessary to reject the status quo for something freer and more contemporary. Doing that meant criticizing old-guard designers, who believed design should be simple—clean on tight grids and Helveticized.” “Do you mean bland?” he quizzed further. “Maybe some of it was bland!” I conceded. “But it was more like a new generation was feeling its oats and it was inevitable.” New technology was making unprecedented options possible. Aesthetic standards were changing because young designers wanted to try everything, while the older, especially the devout Modern ones, believed everything had already been tried. “I read that Massimo Vignelli called a lot of the new digital and retro stuff ‘garbage,’” he said. “What did you say or do about it back then?” “I was more or less on the Modernist side and wrote about it in a 1993 Eye magazine essay called ‘Cult of the Ugly.’” I wasn’t against illegibility per se, just the stuff that seemed to be done badly. I justified biased distinctions not between beauty and ugly, but between good ugly and bad ugly, or what was done with an experimental rationale and with merely style and fashion as the motive. -

How to Re-Shine Depeche Mode on Album Covers

Sociology Study, December 2015, Vol. 5, No. 12, 920‐930 D doi: 10.17265/2159‐5526/2015.12.003 DAVID PUBLISHING Simple but Dominant: How to Reshine Depeche Mode on Album Covers After 80’s Cinla Sekera Abstract The aim of this paper is to analyze the album covers of English band Depeche Mode after 80’s according to the principles of graphic design. Established in 1980, the musical style of the band was turned from synth‐pop to new wave, from new wave to electronic, dance, and alternative‐rock in decades, but their message stayed as it was: A non‐hypocritical, humanist, and decent manner against what is wrong and in love sincerely. As a graphic design product, album covers are pre‐print design solutions of two dimensional surfaces. Graphic design, as a design field, has its own elements and principles. Visual elements and typography are the two components which should unite with the help of the six main principles which are: unity/harmony; balance; hierarchy; scale/proportion; dominance/emphasis; and similarity and contrast. All album covers of Depeche Mode after 80’s were designed in a simple but dominant way in order to form a unique style. On every album cover, there are huge color, size, tone, and location contrasts which concluded in simple domination; domination of a non‐hypocritical, humanist, and decent manner against what is wrong and in love sincerely. Keywords Graphic design, album cover, design principles, dominance, Depeche Mode Design is the formal and functional features graphic design are line, shape, color, value, texture, determination process, made before the production of and space. -

Linotype Matrix 4.2—The Legend Continues

Mergenthaler Edition releases second issue of the new Linotype Matrix Linotype Matrix 4.2—the legend continues. Bad Homburg, 16 May 2006. Following its highly successful relaunch of Linotype Matrix in magazine format last year, Linotype’s publishing label, Mergenthaler Edition, is now releasing the second issue of the classic typographic journal. Linotype Matrix Issue 4.2 takes an exciting and informative look at typography in history – with a thematic focus on the great 20th century type designer William Addison Dwiggins. Within the 64 pages of this richly illustrated issue readers will find articles contributed by some of the best talents working in typography today. For instance, writer and typographer John D. Berry explores the legacy of the Deberny & Peignot type foundry, while the article on Dwiggins’ life and work has been penned by type designer and scholar Paul Shaw, an established Dwiggins authority. Additionally, renowned type historian Sylvia Werfel takes a look at how type systems make designing texts easier. 2006 marks the 50th anniversary of W. A. Dwiggins’ death—an appropriate moment to look back at the contributions of one of the first truly significant type designers from the U.S. As Paul Shaw is currently working on a doctoral dissertation at Columbia University about Dwiggins, he is able to offer an in- depth look at his prolific career as an illustrator, and tells us how, in his late forties, he began a second remarkable career in typeface design at Linotype. Dwiggins was, in fact, the first major type designer to work for the Mergenthaler Linotype Co. in New York and was responsible for creating many great designs, including Metro and Electra, and his most enduring typeface, Caledonia.