894 Slavic Review of Qualification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM HEINEMANN: AUSTRALIA First published in 1987 by HEINEMANN PUBLISHERS AUSTRALIA (A division of Octopus Publishing Group/Australia Pty Ltd) 85 Abinger Street, Richmond, Victoria, 3121. Copyright (c) 1987 by Peter Wright ISBN 0-85561-166-9 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. TO MY WIFE LOIS Prologue For years I had wondered what the last day would be like. In January 1976 after two decades in the top echelons of the British Security Service, MI5, it was time to rejoin the real world. I emerged for the final time from Euston Road tube station. The winter sun shone brightly as I made my way down Gower Street toward Trafalgar Square. Fifty yards on I turned into the unmarked entrance to an anonymous office block. Tucked between an art college and a hospital stood the unlikely headquarters of British Counterespionage. I showed my pass to the policeman standing discreetly in the reception alcove and took one of the specially programmed lifts which carry senior officers to the sixth-floor inner sanctum. I walked silently down the corridor to my room next to the Director-General's suite. The offices were quiet. Far below I could hear the rumble of tube trains carrying commuters to the West End. I unlocked my door. In front of me stood the essential tools of the intelligence officer’s trade - a desk, two telephones, one scrambled for outside calls, and to one side a large green metal safe with an oversized combination lock on the front. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I

JEWISH REVIEW Number 2, Summer 2010 $6.95 OF BOOKS Ruth R. Wisse The Poet from Vilna Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I. Cohen on Camondo Treasure David Sorkin on Steven J. Moses Zipperstein Montefiore The Spy who Came from the Shtetl Anita Shapira The Kibbutz and the State Robert Alter Yehuda Halevi Moshe Halbertal How Not to Pray Walter Russell Mead Christian Zionism Plus Summer Fiction, Crusaders Vanquished & More A Short History of the Jews Michael Brenner Editor Translated by Jeremiah Riemer Abraham Socher “Drawing on the best recent scholarship and wearing his formidable learning lightly, Michael Publisher Brenner has produced a remarkable synoptic survey of Jewish history. His book must be considered a standard against which all such efforts to master and make sense of the Jewish Eric Cohen past should be measured.” —Stephen J. Whitfield, Brandeis University Sr. Contributing Editor Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-14351-4 July Allan Arkush Editorial Board Robert Alter The Rebbe Shlomo Avineri The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson Leora Batnitzky Samuel Heilman & Menachem Friedman Ruth Gavison “Brilliant, well-researched, and sure to be controversial, The Rebbe is the most important Moshe Halbertal biography of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson ever to appear. Samuel Heilman and Hillel Halkin Menachem Friedman, two of the world’s foremost sociologists of religion, have produced a Jon D. Levenson landmark study of Chabad, religious messianism, and one of the greatest spiritual figures of the twentieth century.” Anita Shapira —Jonathan D. Sarna, author of American Judaism: A History Michael Walzer Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-13888-6 J. -

Scopeofsovietact2730unit.Pdf

POSITORT SCOPE OF SOVIET ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERNAL SECURITY ACT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE EIGHTY-FOURTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON SCOPE OF SOVIET ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES JUNE 12 AND 14, 1956 PART 27 (With Sketch of the Career of J. Peters) Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72723 WASHINGTON : 1956 vsoTieo Boston Public Library Superintendent of Document* JAN 2 8 1957- COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JAMES 0. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman ESTDS KEFAUVER, Tennessee ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina WILLIAM LANGER, North Dakota THOMAS C. HENNINGS, Jr., Missouri WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah PRICE DANIEL, Texas EVERETT McKINLEY DIRKSEN, Illinois JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming HERMAN WELKER, Idaho MATTHEW M. NEELY, West Virginia JOHN MARSHALL BUTLER, Maryland Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah THOMAS C. HENNINGS, Jr., Missouri HERMAN WELKER, Idaho PRICE DANIEL, Texas JOHN MARSHALL BUTLER, Maryland Robert Morris, Chief Counsel William A. Rosher, Administrative Counsel Benjamin Mandel, Director of Research n CONTENTS Witnesses : Page Dodd, Bella V 1467 Munsell, Alexander E. O 1463 APPENDIX The career of J. Peters 1483 in SCOPE OF SOVIET ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 1956 United States Senate, Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, Washington, D. -

The Curious Case of Mark Zborowski and the Writing of a Modern Jewish Classic

READINGS Underground Man: The Curious Case of Mark Zborowski and the Writing of a Modern Jewish Classic BY STEVEN J. ZIPPERSTEIN he most in!uential of all popular render- Eastern Wall,” in Fiddler on the Roof, he is actually Trotsky’s son, Lev, along with many others, was ings of Eastern European Jewry in the versifying a passage from the second chapter of Life is dead, his GPU handlers tried to get him to Trotsky’s English language and, arguably, the book with People: “the men who sit along the Eastern Wall lair in Coyoacan, Mexico in order “to get to the that Jewish historians of the region loathe are pre-eminently the learned and the rabbi . .” Later OLD MAN.” Zborowski, however, appears to have Tmore than any other, is Life is with People. Few books editions of the Schocken paperback featured a blurb preferred to continue his anthropological studies at written in the last half-century have more resolutely the Sorbonne, and contrived to remain in Paris. In enveloped the Eastern European Jewish past in nos- When Tevye sings “If I were Richard Lourie’s 1999 !e Autobiography of Joseph talgic amber. It was, to be sure, only one of a cascade Stalin: A Novel, Stalin muses about his gratitude to of books, some of them translated from Yiddish, that a rich man …,” he is actually Zborowski whose reports, he says, are “concise, to sought to do much the same thing in the midst or the the point without a wasted word.” In the 1956 Sen- immediate wake of Hitler’s war, among them Mau- versifying a passage from ate subcommittee hearing which would eventually rice Samuel’s !e World of Shalom Aleichem, Bella lead to his conviction and imprisonment for per- Chagall’s memoir Burning Lights, Abraham Joshua Life is with People. -

Eastland Collection File Series 4: Legislative Files Subseries 11: Internal Security Subcommittee Library

JAMES O. EASTLAND COLLECTION FILE SERIES 4: LEGISLATIVE FILES SUBSERIES 11: INTERNAL SECURITY SUBCOMMITTEE LIBRARY The U.S. Senate eliminated the Internal Security Subcommittee in 1977. In 1977-78, Senator James O. Eastland began transferring his congressional papers to the University of Mississippi. Among the items shipped were publications from the subcommittee’s library. Due to storage space concerns and the wide availability of many titles, the volumes were not preserved in toto. However, this subseries provides a complete bibliographic listing of the publications received as well as descriptions of stamps, inscriptions, or enclosures. The archives did retain documents enclosed within the Internal Security Subcommittee’s library volumes and these appear in Box 1 of this subseries. The bibliographic citation that follows will indicate the appropriate folder number. Call numbers and links to catalog records are provided when copies of the books are in the stacks of the J.D. Williams Library or Special Collections. Researchers should note that these are not necessarily the same copies that were in the Internal Security Subcommittee library or even the same editions. If the publications were previously held by the Internal Security Subcommittee, the library catalog record will note James O. Eastland’s name in the collector field. 24th Congress of the CPSU Information Bulletin 7-8, 1971. Prague, Czechoslovakia: Peace and Socialism Publishers, [1971]. Enclosed: two advertisements from bookseller Progress Books. Enclosed items retained in Folder 1-1. Mildred Adams, ed. Latin America: Evolution or Explosion? New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1963. Stamped: “Received/Jun 3 1963/Int. Sec. S-Comm.” Call Number: F1414 C774 1962. -

Socialist Party of New York, Left Wing Branches

~ '" :, ..... Published Weekly as the Organ of the Socialist Party of New York, Left Wing Branches. Vol. 1. - No. 11. ~ 401 Saturday, October 23, 1937 5 Cents per Copy, • • -~ nlon nl ove MoreS.P.~cals AfL-CIO To Confer in EndorseChlcagow he N W k Left Wing Meet as Ington ext ee The decision of the Denver conventi 011 of the American Federation of Labor ani " Growing responl'e in the Locals and branches of the Socialist of the Atlantic City meeting of the heads of the Committee for Industrial Organiza Party to the call f()l' an emergency convention on November 25th tion to have committees from the two bodies meet in Washington during the week of. in Chicago to deal with the Party crisis, indicates a widespread October 25 for the purpose of discussing the disputes that haw divided the two move interest which gual'antees complete national representation when ments, was the first important step taken since the split toward~ healing the two-year the convention "es~ions open. The announcement was made by James old breach in the ranks of American orga nized labor. P. Cannon, seCl"etary of the Convention Arrangements Committee ~ ----------------~---------------------------- in New York. The call for the~------------- 8,000,000 Involved of between seven and eight in the rank and file of both or convention was issued three weeks mil-I tentiary for "embezzlement" of Should the joint confer-Ilion members-more than have ganizations for unity, the ab~ence ago in the name of the State Ex party property which duly be ever been enrolled in American \ of which has had such painful ecutive Committees of the Social longed to the left wing. -

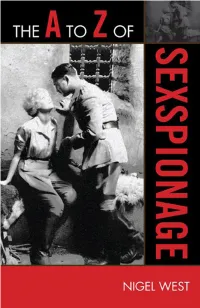

Nigel West, 2009

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19. -

**A Note on Citations for the Information and Intrigue, America's

**A Note on Citations for the Information and Intrigue, America’s Information Wars and Related Works ** Because of number-of-pages limitations, we decided to limit the number and length of citations and endnotes in the texts and to employ as many space-saving formats as possible. If we used traditional approaches to citing and using notes, the texts would have been unbearably long. However, despite the citing parsimony we feel that readers will be more than adequately pointed to evidence and sources. Illustrative Bibliography, Information and Intrigue and Related Volumes, May, 2018 This bibliography contains some of the more important and more readily available secondary works used in the project. For the primary documents and their sources, see the texts. Copyright, Colin Burke, 2010 Abbott, Andrew, “Library Research Infrastructure for Humanistic and Social Scientific Scholarship in the Twentieth Century”, in, Charles Camic, et al. (eds.), Social Knowledge in the Making (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 43-87. Abrams, Richard A., "A Paradox of progressivism: Massachusetts on the Eve of Insurgency," Political Science Quarterly, 75 3 (Sept., 1960: 379-399). Abrams, Richard M., Conservatism in a Progressive Era: Massachusetts Politics 1900-1912 (Cambridge, MA Harvard University Press, 1964). Abt, John, Advocate and Activist: Memoirs of an American Lawyer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993). Adams, Mark B., et al., “Human Heredity and Politics: a Comparative Study of the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor…,” OSIRIS 2nd Series, 20 1 (n.d.): 232-62. Adams, Scott, “Information for Science and Technology,” (Urbana: University of Illinois GLIS 109, 1945). Adkinson, Burton W., Two Centuries of Federal Information (Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross, 1978). -

Rezension Über: Boris Volodarsky, Stalin's Agent. The

Citation style Znamenski, Andrei: Rezension über: Boris Volodarsky, Stalin's Agent. The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, in: Reviews in History, 2015, November, DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/1861, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1861 copyright This article may be downloaded and/or used within the private copying exemption. Any further use without permission of the rights owner shall be subject to legal licences (§§ 44a-63a UrhG / German Copyright Act). Stalin’s Agent is a biography of one of Stalin’s illegals who was known by the alias of Alexander Orlov (1895–1973). Orlov entered the history of Soviet espionage primarily due to three reasons: First, he was credited with presiding over the shipment of 500 tons of Spainish gold reserve to Moscow in 1936, thus effectively stripping the country of her assets in exchange for limited supplies of military equipment to republican Spain. Second, in fear of being executed by his paranoid bosses, who cannibalized the Soviet secret services cadre during the 1937–9 Great Terror, Orlov brilliantly outmaneuvered Stalin’s agents and defected (along with his wife and daughter) to North America. Moreover, rather than leaving empty-handed, he took $68,000, the entire operational fund he stole from the Soviet station in Spain, in addition to $22,800 he claimed he had ‘saved’. With this nice chunk of cash (an equivalent of $1,500,000 in present money), Orlov lived quietly, laying low until 1953. Third, that same year when the Soviet dictator died, he again played his cards right, immediately ‘coming out of the closet’ and making a name for himself with a bestselling book The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes (1953). -

"Only Trotskyism Can Defend the Gains of October" - ET Bulletin No

TROTSKYIST BULLETIN No. I "Only TrotskyismCan Defend the Gains of October" A debate between the External Tendency of the international Spartacist tendency and the leadership of the Spartacist League/US on Soviet defensism and the nature of the Kremlin bureaucracy. External Tendency of the iSt TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................... .......... ................. .... ........ i "You Can't Defend the Soviet Union with Yuri Andropovs" - ET Bulletin No. 1, August 1983 .•.................•........ 1 "Correspondence with Robertson" - ET Bulletin No. 2, January 1984 Letter from James Robertson, 6 August 1983.............. 2 Reply by ET, 28 October 1983............................ 3 "Only Trotskyism Can Defend the Gains of October" - ET Bulletin No. 3, May 1984 Letter from Reuben Samuels, 3 January 1983 •..•..•....••. 6 Rep1 y by ET ' 2 2 Apri 1 198 4 . • . • . • . • . • 9 Appendix: "Andropov as Ambassador"..................... 16 "Poland: No Responsibility for Stalinist Crimes!" - ET Bulletin No. 1, August 1983 .•. .......•.........•... ...• 18 "A Textbook Example" - ET Bulletin No. 2, January 1984. • . • • . .. .. .. 19 "iSt Betrays Indochinese Trotskyist Heritage" - ET Bulletin No. 2, January 1984 . • . • . • . • . • . • . 20 Pref ace The material in this pamphlet is chiefly comprised of polemics between the External Tendency of the international Spartacist tendency (ET -- a grouping of former members of the iSt) and the leadership of the Spartacist League/U.S. (SL). It begins with a letter from the ET to the SL criticizing the decision to designate a busload of SL supporters attending an anti-fascist rally as the "Yuri Andropov Brigade." SL leader James Robertson's reply to this letter, as well as our rejoinder and a subsequent exchange with one of the SL's scribes, Reuben Samuels, complete this correspondence. -

Hede Massing Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6m3nf2s4 No online items Inventory of the Hede Massing papers Finding aid prepared by Sally DeBauche Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2008 Inventory of the Hede Massing 83038 1 papers Title: Hede Massing papers Date (inclusive): 1918-1980 Collection Number: 83038 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: In English and German. Physical Description: 2 manuscript boxes(0.8 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, police reports, clippings, and photographs, relating to Soviet espionage activities in the United States. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Massing, Hede. Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Hede Massing papers, [Box number], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1983. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu/ . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid.