Half Rhymes in Japanese Rap Lyrics and Knowledge of Similarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

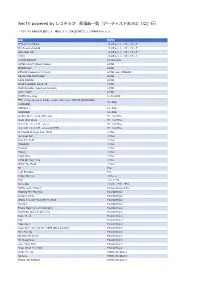

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Commencement

2020 COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH DAKOTA THE ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-THIRD ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES SANFORD COYOTE SPORTS CENTER VERMILLION, SD OCTOBER 24, 2020 Graduate & Undergraduate Commencement Sanford Coyote Sports Center October 24, 2020 9:00 a.m. The Commencement Procession The National Anthem Welcome Dr. Rob Turner, University Senate Chair Sheila K. Gestring, President Belbas-Larson Awards for Excellence in Teaching Kurt Hackemer, Provost & Vice President for Academic Affairs Associate Professor Shane Nordyke, College of Arts & Science Assistant Professor Lisa Ann Robertson, College of Arts & Sciences Commencement Address Colonel Inès N. White Hooding and Conferring of Doctoral Candidates and Presentation of Diplomas Doctor of Philosophy Doctor of Education Doctor of Audiology Docotor of Occupational Therapy Doctor of Physical Therapy Transitional Doctor of Physical Therapy Doctor of Medicine Juris Doctor Conferring of Specialist and Master Degrees and Presentation of Diplomas Specialist in Education Master of Arts Master of Business Administration Master of Fine Arts Master of Music Master of Professional Accountancy Executive Master of Public Administration Master of Public Administration Master of Public Health Master of Science Master of Social Work Conferring of Baccalaureate and Associate Degrees Induction into Alumni Association Steve Young, Alumni Association Representative University Hymn, Alma Mater Closing Remarks Sheila K. Gestring, President Dr. Rob Turner, University Senate Chair Recessional Note to Guests: The audience will remain seated for both the Processional and Recessional and will rise for the National Anthem and Alma Mater. Professional photographs by Lifetouch Photography will be available a week after the ceremony at www.usd.edu/registrar/commencement.cfm. University President Sheila K. -

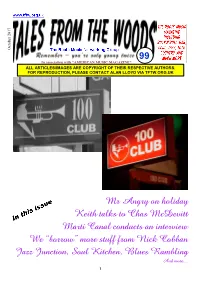

Mr Angry on Holiday Keith Talks to Chas

October 2017 October 99 In association with "AMERICAN MUSIC MAGAZINE" ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Mr Angry on holiday Keith talks to Chas McDevitt Marti Canal conducts an interview We “borrow” more stuff from Nick Cobban Jazz Junction, Soul Kitchen, Blues Rambling And more.... 1 2 Emma Peel (who doesn’t have the faintest idea why she’s here but dealt with many odd situations in her time with The Avengers) says: “ HOLD THE THIRD PAGE! ” Hi Gang. Welcome to the autumn edition of Tales From The Woods magazine, a busy time for us all at this moment in time. At the end of this very month of October we shall be at London’s legendary 100 Club, and we all here at TFTW are in a state of excited anticipation in readiness for our return to this, the oldest music venue in London and possibly the UK, that has seen countless venues come and go, some lost to the passage of time since it first opened its doors in the heart of London’s west end amidst the carnage and destruction of World War II an incredible 75 years ago. The legend that is our wonderful headliner, Tommy Hunt, former member of doo- wop royalty in his native USA with The Flamingos, later to have huge hits and following as a bona fide soul man, a particular hero on the British northern soul circuit, is so looking forward to performing for us, on a show dedicated to that golden age of doo-wop back in the late fifties and early sixties. -

Fahitiers .Evdcijees

4 Vol. I, 140. 6 Amacule, Colorado Novemb~2a!9±~._. .EVDCIJEES A~D FAHITIERS Real Property ML GIRLS VOLUNTEERS SONA TI NA S HARVEST BEETS Taxes Due In. answer to the pleas Los Angeles county real “Lea Sonatinas”, a mu sical organization of 21 of local beet farmers, who property taxes will be de werE. threatened witha loss linquent after December 5, young women, will give a concert at Terry hail, Tues of 60,000 tons, the assem counsels Chiyoko sakamoto bly voted unanimously to’ of the legal aid staff. day, Nov. 17 at 2 p.m. The organiZ4tiOn is un come to the aid of farmer Write to H. L. Byrani, neighbors. county tax collector, hail der the direction of C. Already 141 volunteers Burdette Wolfe, supervisor of Justice, Los Angeles. including 20 high school of music programs for the Taxpayers should gi.ve students and five women Garden city high school and full legal description of junior college in Kansas. have relliedill this nation property and certificate Tickets are now on sale wide crop—savins c~mpa~gn. According. to the admin of title or previous cadnty at the school offices in istration, the woit orders tax bill. BE. prices will be adults 25 cents, and children 10 of those emplçyed within tent a. the center wIll not be can TWO STE ND celled luring ithelr abseftie. Student volunteers will be CONVENT! ON Fire Alarm given an opportunitY to Henry tshimizu, former make up their classwork. Sonoina-~coU1ftY JACL.presi— System Set Deductions for morning dent, and tttasao Satow, a Fire phones have been and evening meals will member of the National JACL placed In each center block total 44 cents; for all emergency board, -are ax— and can be recognized by a meals, including packed pectéd to.leave the center lunches, 67 cents. -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi -

애니송북 제19탄 2020년 여름호 모바일용.Xlsx

1, 애니 송 (일본) ♪ 3월의 라이온 orion 44128 米津玄師 요네즈켄시 4월은 너의 거짓말 オレンジ 44269 7!! 오렌지 キラメキ 44177 wacci 키라메키 光るなら 43859 Goose house 히카루나라 5등분의 신부 五等分の気持ち 44385 中野家の五つ子 고토분노 키모치 나카노케노 이츠츠고 BORUTO-보루토- バトンロード 44388 KANA-BOON 바톤 로드 B-PROJECT 快感*エブリディ 44554 B-PROJECT 카이칸 에브리데이 C マトリョーシカ 44006 NICO Touches 마트료시카 the Walls DARKER THAN BLACK From Dusk Till Dawn 43172 abingdon boys school HOWLING 42435 abingdon boys school 覚醒ヒロイズム~THE HERO WITHOUT.. 42720 アンティック-珈琲店- 카쿠세이 히로이즘 앤티크 커피점 ツキアカリのミチシルベ 43158 ステレオポニー 츠키아카리노 미치시루베 스테레오포니 GOSICK -고식- Destin Histoire 43355 yoshiki*lisa GTO Driver's High 41185 L'Arc~en~Ciel しずく 41213 奥田美和子 시즈쿠 오쿠다미와코 ヒトリノ夜 41237 Porno 히토리노 요루 Graffitti J리그 위닝일레븐 택틱스 本日ハ晴天ナリ 42082 Do As 혼지츠와 세이텐나리 Infinity NARUTO-나루토- ALIVE 40572 雷鼓 라이코 CLOSER 43013 井上ジョー 이노우에죠 Ding! Dong! Dang! 40070 TUBE Diver 43856 NICO Touches the Walls GO!!! 41759 FLOW Hero's Come Back!! 42526 nobodyknows+ if 43269 西野カナ 니시노카나 Lie-Lie-Lie 42510 DJ OZMA Sign 43872 FLOW wind 44381 Akeboshi (와인드) うたかた花火 43696 supercell 우타카타하나비 悲しみをやさしさに 41673 little 카나시미오 야사시사니 by little 言葉のいらない約束 44283 sana 코토바노 이라나이 야쿠소쿠 シルエット 43862 KANA-BOON 실루엣 青春狂騒曲 40500 Sambo Master 세이슝쿄소쿄쿠 透明だった世界 44047 秦基博 토메이닷타 세카이 하타모토히로 ニワカ雨ニモ負ケズ 43882 NICO Touches 니와카아메니모 마케즈 the Walls 遥か彼方 41835 ASIAN KUNG-FU 하루카 카나타 GENERATION ハルモニア 41979 RYTHEM 하르모니아 ブルーバード 42815 いきものがかり 블루버드 이키모노가카리 ホタルノヒカリ 43109 いきものがかり 호타루노 히카리 이키모노가카리 ラヴァーズ 43931 7!! 러버즈 가자 83084 펄스데이 너는 내게... 69551 토리 너를 보낸 나의 2야기 45479 장연주 오직 너만이 85220 이용신 투지 45657 버즈(Buzz) 풍운 88609 이승열 활주 45293 버즈(Buzz) NHK에 어서오세요! 踊る赤ちゃん人間 42233 大槻ケンヂと. -

2015 Spring Commencement Metropolitan State University of Denver

2015 SPRING COMMENCEMENT METROPOLITAN STATE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2015 SPRING COMMENCEMENT SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2015 Letter from the President .......................... 2 MSU Denver: Transforming Lives, Communities and Higher Education .... 3 Marshals, Commencement Planning Committee, Retirees ............ 4 In Memoriam, Board of Trustees ............. 5 Academic Regalia ....................................... 6 Academic Colors ......................................... 7 Provost’s Award Recipient ......................... 8 Morning Ceremony Program .................... 9 President’s Award Recipient ................... 10 Afternoon Ceremony Program ................ 11 Morning Ceremony Candidates School of Education and College of Letters, Arts and Sciences ........................................ 12 Afternoon Ceremony Candidates College of Business and College of Professional Studies ..........20 Seating Diagrams ................................….27 1 DEAR 2015 SPRING GRADUATION CANDIDATES: Congratulations to you, our newest graduates! And welcome to your families and friends who have anticipated this day — this triumph — with immense pride. Each of our more than 80,000 graduates is unique, but all have one thing in common: Their lives were transformed by the education they received at MSU Denver. Most have stayed in Colorado, where they teach our children, own small businesses, create beautiful works of art, counsel families in crisis and design cutting-edge products that improve our lives. They are role models who have infused our state and their neighborhoods with economic growth, civic responsibility and culture. They have seized the opportunity to transform their families and their communities. Now it is your time to begin making the most of all that you have learned! MSU Denver transformed higher education in Colorado when, 50 years ago in the fall of 1965, we opened our doors with six majors, 1,187 students and a mission to give the opportunity to earn a college degree to almost anyone willing to take on the challenge. -

Sri Lanka Luxury Stays Best Somatheeram of Kerala Shopping Woven Dreams of Desire

FOOD STOPS: SOUTHERN INDIA & MUMBAI MagazineEXPLORE CONTEMPORARY INDIA & SOUTH ASIA MALAYSIA EDITION JANUARY 2014 PLUS Private Jet Charter Astrology & Travel Sri Lanka Luxury Stays BEST Somatheeram of Kerala SHOPPING Woven Dreams of Desire COVER STORY ROYAL TREATMENT at Indian Forts & Palaces CKS_Embassy_of_India_AW150114.pdf 1 1/15/14 3:35 PM EXPLORE CONTEMPORARY INDIA & SOUTH ASIA MALAYSIA EDITION 11 04 Editor’s Note 05 Contributor’s Page COVER FEATURE 06 Indian Forts & Places - The Royal Treatment The elegant, the subtle, the whimsical and the bizarre! The range of palaces boggles the mind! FEATURES 11 Winter Thrills in India’s Alpine Country Stunning scenery, skiing and snowboarding in India’s DESTINATION Himalayan retreats 26 Olde Banglore Beckons The quiet side of India’s Silicon 34 Starry Journeys - Where to Go Valley Look to the stars for your next travel destination! BLOGGERS’ TALES 16 R Niranjan Das - Vythiri: The Emerald Gateway IN PERSON 17 Anuradha Goyal - Bewitching Personal travel accounts of Bomdila Southeast Asian travellers 18 Puru - Nalanda: Lost Knowledge 29 Malaysia: Kashmir is Heaven on Earth fACES & PLACES 19 Mandip Singh Soin THE WELLNESS DESTINATION Adventure is My Business 30 Foods that Heal Exploring India’s Adventure tourism sector INDIA - A SPIRITUAL JOURNEY LUXE LIFE 30 Jewels of Jainism 14 Private Jet Charter 31 Bodhisattva Bhumi - The Uber luxury way of Buddha’s Land destination hopping in India 14 33 Travel Trade Fairs & Events 2 3 46 24 11 FOOD STOPS 24 Flavour of Southern India 42 and Mumbai A literary tour with recipes and a Michelin chef food guide to Mumbai WELLNESS & SPA 36 Somatheeram Ayurvedic Hospital & Yoga Centre: The Best of the Best in Kerala SHOPPING 38 Woven Dreams of Desire Regional guide to fine carpets and floor coverings of India IN SEARCH OF.. -

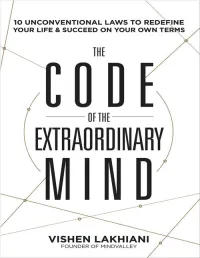

The Code of the Extraordinary Mind: 10 Unconventional Laws To

To my family: Kristina, Hayden, and Eve. You’re the most important thing in my life. And to our parents, Mohan and Roopi, Virgo and Ljubov, for allowing us to forge our own beliefs and question the Brules, even as kids. CONTENTS Before You Begin: Know That This Is Not Your Typical Book Introduction PART I: LIVING IN THE CULTURESCAPE: HOW YOU WERE SHAPED BY THE WORLD AROUND YOU CHAPTER 1 Transcend the Culturescape Where We Learn to Question the Rules of the World We Live In CHAPTER 2 Question the Brules Where We Learn That Much of How the World Runs Is Based on Bulls**t Rules Passed Down from Generation to Generation PART II: THE AWAKENING: THE POWER TO CHOOSE YOUR VERSION OF THE WORLD CHAPTER 3 Practice Consciousness Engineering Where We Learn How to Accelerate Our Growth by Consciously Choosing What to Accept or Reject from the Culturescape CHAPTER 4 Rewrite Your Models of Reality Where We Learn to Choose and Upgrade Our Beliefs CHAPTER 5 Upgrade Your Systems for Living Where We Discover How to Get Better at Life by Constantly Updating Our Daily Systems PART III: RECODING YOURSELF: TRANSFORMING YOUR INNER WORLD CHAPTER 6 Bend Reality Where We Identify the Ultimate State of Human Existence CHAPTER 7 Live in Blissipline Where We Learn about the Important Discipline of Maintaining Daily Bliss CHAPTER 8 Create a Vision for Your Future Where We Learn How to Make Sure That the Goals We’re Chasing Will Really Lead to Long-Term Happiness PART IV: BECOMING EXTRAORDINARY: CHANGING THE WORLD CHAPTER 9 Be Unfuckwithable Where We Learn How to Be Fear-Proof CHAPTER 10 Embrace Your Quest Where We Learn How to Put It All Together and Live a Life of Meaning Appendix: Tools for Your Journey The Code of the Extraordinary Mind: The Online Experience Glossary Sources Acknowledgments BEFORE YOU BEGIN: KNOW THAT THIS IS NOT YOUR TYPICAL BOOK In fact, I would be hesitant to call this a personal growth book. -

College of EDUCATION & Human Development

C E & H D BOARD OF REGENTS Jaime R. Garza, Chairman San Antonio Rossanna Salazar, Vice Chairman Austin Charlie Amato San Antonio Veronica Muzquiz Edwards San Antonio David Montagne Beaumont Vernon Reaser III Bellaire William F. Scott Nederland Alan L. Tinsley Madisonville Donna N. Williams Arlington Spencer Copeland, Student Regent Huntsville Brian McCall, Ph.D., Chancellor UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATION Kenneth R. Evans, Ph.D. President James Marquart, Ph.D. Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Kevin B. Smith, Ph.D. Senior Associate Provost Brenda S. Nichols, D.N.Sc. Associate Provost Cruse D. Melvin, Ph.D. Vice President for Finance and Operations Priscilla Parsons, M.B.A. Vice President for Information Technology Vicki McNeil, Ed.D. Vice President for Student Engagement Juan Zabala, M.B.A. Vice President for University Advancement Jason Henderson, M.B.A. Athletics Director ACADEMIC DEANS William E. Harn, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate Studies Joe Nordgren, Ph.D. Interim Dean of Arts and Sciences Enrique “Henry” Venta, Ph.D. Dean of Business Robert Spina, Ph.D., FACSM Dean of Education and Human Development Srinivas Palanki, Ph.D. Dean of Engineering Derina Holtzhausen, Ph.D. Dean of Fine Arts and Communication Kevin Dodson, Ph.D. Dean of Reaud Honors College David J. Carroll, M.L.S. Director of Library Services It is a pleasure to welcome you to the May 2016 Commencement Ceremony for the College of Education and Human Development at Lamar University. This is a time for us to recognize and honor our graduates for their hard work and achievements. It also is a time to express appreciation to those who have encouraged and helped support our students who are graduating today. -

Larimer Campus Commencement 2019-2020

College Leadership College Administration Andrew R. Dorsey Gillian McKnight-Tutein, Ed.D. President Vice President, Student & Academic Affairs Catherine Pellish Vice President, Tamara White Westminster/North Metro Associate Vice President, Student Support & Enrollment Services Elena Sandoval-Lucero, Ph.D. Vice President, Derek Brown Boulder County Campus Associate Vice President, Facilities Planning & Management, Jean Runyon, Ph.D. Finance & Administration Vice President, Larimer Campus Stacey Hogan, Ph.D. Associate Vice President, Patricia Arroyo Strategic Planning & Vice President, Institutional Effectiveness Finance & Administration Larimer Campus Kyla Antony, M.Ed. Nicholas Spezza, D.M. Administration Dean of Student Affairs Dean of Instruction Darcy Orozco, Ph.D. Shashi Unnithan, Ph.D. Dean of Instruction Dean of Instruction 2 Commencement 2019–2020 LARIMER CAMPUS College Leadership State Board for Chancellor Joe Garcia Voting Members Community Colleges System President Presley F. Askew Maria-Vittoria Carminati The Honorable S.R. Heath Richard Garcia Chair Landon Mascareñaz Terrance McWilliams Russell J. Meyer Hanna Skandera Vice-Chair Daniel Villanueva Front Range Community Board of Directors Ms. Alvina Vasquez College Foundation Mr. Ryan Tharp Ms. Heidi Williams Chair Director Emeritus Ms. Kristen Bernhardt Ms. Teri DePuy Ms. Micheline Burger Ms. Nancy Hamilton Mr. Tom Cassady Mr. Harold Henke Mr. Terry Dye Mr. Jeffrey Knight Mr. William Hillen III Mr. Martin Ruffalo Ms. Katherine Kimball Ms. Marty Marsh Ms. Marilee Menard Mr. Rick Samson College Area Wayne L. Anderson Don Oest Advisory Council Executive Leadership Coach & CEO, Senior Instructor, Leadership Science Institute, LLC University of Colorado-Boulder, Leeds School of Business Darin Atteberry City Manager, Elvira Ramos City of Fort Collins Retired, Vice President, Programs and Inclusive Leadership , Jacob Castillo The Community Foundation Boulder Director, County Larimer County Workforce Center Sandra Steiner Patrick J. -

Criminal Cases Disposed Case Closed Between: 8/1/2021 to 9/27/2021 Listed by Court Location Anchorage Sunday, August 1, 2021 3AN-21-05705CR SOA Vs

Alaska Court System Criminal Cases Disposed Case Closed Between: 8/1/2021 to 9/27/2021 Listed by Court Location Anchorage Sunday, August 1, 2021 3AN-21-05705CR SOA vs. Mercado-Robison, Elmer Noel DOB: 10/18/1973 ATN: 117633222 Case Disposed: 08/01/2021 1 07/31/2021 Charging Document Pending or Not Filed 3AN-21-05706CR MOA vs. Reynolds II, Clyde Edison DOB: 06/22/1977 ATN: 118298034 Case Disposed: 08/01/2021 1 07/31/2021 Charging Document Pending or Not Filed 3AN-21-05709CR MOA vs. Uttereyuk, Zachary Ross DOB: 06/03/2001 ATN: 117636237 Case Disposed: 08/01/2021 1 08/01/2021 Charging Document Pending or Not Filed 3AN-21-05710CR MOA vs. Birotte, Kimberly Nicole DOB: 04/04/1989 ATN: 118297683 Case Disposed: 08/01/2021 1 08/01/2021 Charging Document Pending or Not Filed Monday, August 2, 2021 3AN-17-00778CR SOA vs. Stutzke, Jesse Steven DOB: 03/06/1991 ATN: 114943662 Case Disposed: 08/02/2021 1 09/25/2016 AS11.41.120(a)(1): Manslaughter -Death Not Murder 1 Or 2 03/21/2017 Charge Refiled 2 09/25/2016 AS11.41.220(a)(1)(B): Assault 3- Cause Injury w/ Weap 08/02/2021 Dismissed by Prosecution (CrR43(a)(1) 3 09/25/2016 AS28.35.030(a)(1): DUI- Alcohol Or Contr Subst 08/02/2021 Guilty Conviction After Guilty Plea 4 09/25/2016 AS11.41.130: Criminally Negligent Homicide 08/02/2021 Guilty Conviction After Guilty Plea 5 09/25/2016 AS11.41.230(a)(1): Assault In The 4th Degree - Recklessly Injure 08/02/2021 Dismissed by Prosecution (CrR43(a)(1) 3AN-19-04895CR SOA vs.