Revitalizing Mi'kmaq Culture in Newfoundland - a Grounded Theory Discursive Analysis of Oppression and Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 Agreement for the Recognition of The

November 30, 2007 Agreement for the Recognition of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq Band FNI DOCUMENT 2007 NOVEMBER 30, 1 November 30, 2007 Table of Contents Parties and Preamble...................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1 Definitions....................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2 General Provisions ......................................................................................... 7 Chapter 3 Band Recognition and Registration .............................................................. 13 Chapter 4 Eligibility and Enrolment ............................................................................... 14 Chapter 5 Federal Programs......................................................................................... 21 Chapter 6 Governance Structure and Leadership Selection ......................................... 21 Chapter 7 Applicable Indian Act Provisions................................................................... 23 Chapter 8 Litigation Settlement, Release and Indemnity............................................... 24 Chapter 9 Ratification.................................................................................................... 25 Chapter 10 Implementation ........................................................................................... 28 Signatures ..................................................................................................................... 30 -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

To View This Month's Newsletter

MAW-PEMITA’JIK QALIPU’K THE CARIBOU ARE TRAVELLING TOGETHER Qalipu’s Newsletter June 2019 1 Contents Inside this issue: Youth Summer Employment Program 3 Special Award for Support of Black 4 Bear Program Update your Ginu Membership Profile 5 Health and Social Division 6 Educating Our Youth 7 Piping Plover Update 8 Bear Witness Day, Sweetgrass 9 Festival Comprehensive Community Plan 10 Indigenous Culture in the Classroom 11 and on the Land Wetlands: an important part of our 12-13 heritage Elders and Youth Breaking the Silence 14 on Mental Health Qalipu First Nation 15 Join our Community Mailing List! You don’t have to be a member of the Band to stay in touch and participate in the many activities happening within our communities. Qalipu welcomes status, non- status, and non-Indigenous people to connect and get involved! Click here to join! 2 Youth Summer Employment Program 2019 THE YOUTH SUMMER EMPLOYMENT PROGRAM provides wage support to community organizations who, in turn, provide Indigenous youth with meaningful employment and skills. Businesses apply for the program and are selected from each of the nine Wards, along with one recipient from locations outside the Wards as well. Indigenous youth can apply directly to these businesses who are successful recipients of the Youth Summer Employment Program. Successful Businesses for Youth Summer Employment Program 2019 “The Youth Summer Employment Program is fabulous. Without the Corner Brook Ward Flat Bay Ward program, my summer camp Noseworthy Law Bay St. George Cultural Revival would not have been a Qalipu Development Corporation Committee success. The student I hired, Shez West Flat Bay Band Inc. -

Maw-Pemita'jik Qalipu'k

Maw-pemita’jik Qalipu’k Pronunciation : [Mow bemmy daa jick ha lee boog] Meaning: The Caribou are travelling together Qalipu’s Monthly Newsletter January 2016 Warm Welcome at St. John’s Native Friendship Centre Following an early morning meeting in St. John’s, Chief Mitchell and Jonathan Strickland, Manager of the Qalipu Natural Resources Division, decided to spend some time visiting the St. John’s Native Friendship Centre before their flight back to the west coast. The visit and subsequent tour turned out to be an eye opener for both; they have returned home full of praise for the centre, and the many cultural, employment, recreation, business and health related programs and services that this place has to offer. The Native Friendship Centre started out with a group of volunteers, offering a few basics programs, in the late 1970’s. At that time, home-base was a small office at Memorial University. It wasn’t until 1983, that the St. John’s Native Friendship Centre was legally established as a non-profit organization. Since then the centre has opened its doors to include the non-native community, has expanded and outgrown several buildings, and has come to employ 20 full time permanent staff, along with many more volunteers. “We didn’t call ahead,” laughs Jonathan, “but, two of the centres lead staff (Natasha McDonald and Briannah Tulk) welcomed us in to their office for an overview of the centre and the work they do. After we chatted, they brought us around for a tour. It’s hard to believe how much is happening there.” Something that stuck with Jonathan was the hostel and community kitchen. -

Labour Market Indicators and Trends

Labour Market Indicators and Trends Stephenville-Port aux Basques Region Strengthening Partnerships in the Labour Market Initiative Report #6 Winter 2007 Labour Market Development Division Department of Human Resources, Labour and Employment The Department of Human Resources, Labour and Employment gratefully acknowledges financial support in the preparation of this report from the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Development Agreement. For more information or additional copies of this document, please contact: Labour Market Development Division Department of Human Resources, Labour and Employment P.O. Box 8700 West Block, Confederation Building St. John’s, NL A1B 4J6 Telephone: (709) 729-2866 Fax: (709) 729-5560 Email to: [email protected] Or download a copy at: www.hrle.gov.nl.ca/hrle/publications/list.htm Readers should note that the text in the PDF version of this document may differ slightly from the printed version. Labour Market Indicators and Trends: Market Indicators and Trends: Labour Labour Market Indicators and Trends Stephenville-Port aux Basques Region Strengthening Partnerships in the Labour Market Initiative aux Basques Region Stephenville-Port Report #6 Department of Human Resources, Labour and Employment Winter 2007 Labour Market Indicators and Trends: Stephenville-Port aux Basques Region Table of Contents TABle OF CONteNTS LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES .................................................................................................................. III Labour Market Indicators and Trends: -

Office Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 REID, SCOTT, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $0.00 Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount Period Activity: 0.00 Opening Balance: 0.00 Ending Balance: 0.00 ---- End of Report ---- House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Rental of Short-term Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 REID, SCOTT, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $0.00 Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount Period Activity: 0.00 Opening Balance: 0.00 Ending Balance: 0.00 ---- End of Report ---- House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Office Start-up Costs 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 REID, SCOTT, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $0.00 Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount Period Activity: 0.00 Opening Balance: 0.00 Ending Balance: 0.00 ---- End of Report ---- House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report -

Coastal Erosion in St. George's

COASTAL EROSION IN ST. GEORGE’S BAY, WESTERN NEWFOUNDLAND M. Irvine Open File 012B/0705 St. John’s, Newfoundland August, 2019 COASTAL EROSION IN ST. GEORGE’S BAY, WESTERN NEWFOUNDLAND M. Irvine Open File 012B/0705 St. John’s, Newfoundland 2019 NOTE Open File reports and maps issued by the Geological Survey Division of the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources are made available for public use. They have not been formally edited or peer reviewed, and are based upon preliminary data and evaluation. The purchaser agrees not to provide a digital reproduction or copy of this product to a third party. Derivative products should acknowledge the source of the data. DISCLAIMER The Geological Survey, a division of the Department of Natural Resources (the “authors and publish- ers”), retains the sole right to the original data and information found in any product produced. The authors and publishers assume no legal liability or responsibility for any alterations, changes or misrep- resentations made by third parties with respect to these products or the original data. Furthermore, the Geological Survey assumes no liability with respect to digital reproductions or copies of original prod- ucts or for derivative products made by third parties. Please consult with the Geological Survey in order to ensure originality and correctness of data and/or products. Recommended citation: Irvine, M. 2019: Coastal erosion in St. George’s Bay, western Newfoundland. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Natural Resources, Geological Survey, St. John’s, Open File 012B/ 0705, 50 pages. Author Address: M. Irvine Terrain Sciences and Geoscience Data Management Section Department of Natural Resources P.O. -

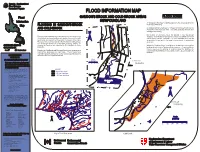

Flood Information Map

Canada - Newfoundland Flood Damage Reduction Program FLOOD INFORMATION MAP Flood GAUDON'S BROOK AND COLD BROOK AREAS FLOOD ZONES NEWFOUNDLAND Information A "designated floodway" (1:20 flood zone) is the area subject to the Map FLOODING IN GAUDON'S BROOK most frequent flooding. AND COLD BROOK A "designated floodway fringe" (1:100 year flood zone) constitutes the remainder of the flood risk area. This area generally receives less damage from flooding. No building or structure should be erected in the "designated Flooding causes damage to personal property, disrupts the lives floodway" since extensive damage may result from deeper and more of individuals and communities, and can be a threat to life itself. swiftly flowing waters. However, it is often desirable, and may be Continuing development of flood plain increases these risks. acceptable, to use land in this area for agricultural or recreational The governments of Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador purposes. are sometimes asked to compensate property owners for GAUDON'S BROOK damage by floods or are expected to find solutions to these Within the "floodway fringe" a building, or an alteration to an existing COLD BROOK problems. building, should receive flood proofing measures. A variety of these may be used, eg. the placing of a dyke around the building, the Canada Newfoundland Flooding at Cold Brook and Gaudon's Brook have occurred as a construction of a building on raised land, or by the special design of a result of ice blockages and high flows. These floods have building. resulted in property damage to nearby residences and erosion to GAUDON'S BROOK the river banks and adjacent farmland. -

Western Newfoundland & Labrador Offshore Area

WESTERN NEWFOUNDLAND & LABRADOR OFFSHORE AREA Strategic Environmental Assessment Update Draft Report Submitted to: Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board 5th Floor TD Place, 140 Water Street St. John's, Newfoundland & Labrador Canada A1C 6H6 Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure A Division of AMEC Americas Limited 133 Crosbie Road, PO Box 13216 St. John's, Newfoundland & Labrador Canada A1B 4A5 May 2013 AMEC TF 1282501 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Nature, Purpose and Context of the SEA Update ........................................................................................ 3 1.2 Document Organization ............................................................................................................................... 4 2 STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT UPDATE: SCOPE, FOCUS AND APPROACH ............................... 5 2.1 The SEA Update and the Associated “Strategic Decision” ........................................................................... 5 2.2 Spatial and Temporal Boundaries ................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 SEA Update: Scoping Document .................................................................................................................. 8 2.4 Consultation Program ................................................................................................................................. -

City of Corner Brook Submission to Electoral Boundaries Commission

CITY OF CORNER BROOK SUBMISSION TO ELECTORAL BOUNDARIES COMMISSION Good evening and thank you for the opportunity to present comments with respect to the proposed boundary changes to the electoral districts in Newfoundland and Labrador. As a Council we fully recognize the difficult task the Commission faces in balancing many competing objectives. Our Council clearly understands the mandate of the Electoral Boundaries Commission. Our presentation today will focus on the proposed districts for Corner Brook and how we feel it will impact our constituents. At the outset I would like to voice our opposition to the reduction of seats from forty-eight to forty. I believe the reduction of seats will have a detrimental impact on rural Newfoundland and particularly communities outside the Avalon Peninsula. It is our overall recommendation that the status quo of forty eight seats in the House of Assembly remain in place. Given that the Commission has submitted a proposal to divide the province into forty districts we submit the following feedback. Under the proposed electoral boundaries districts the City of Corner Brook will be divided among three electoral districts: ● Corner Brook District: Corner Brook residents represent 100 % of the population of this district. This will certainly be advantageous for the residents in this district as constituents will have one member representing the concerns for Corner Brook residents only ● Humber North District: Corner Brook residents make up approximately 31% of the Humber North District which is a very -

Western Health Strategic Plan 2020-2023 Cover Photo by Allan Benoit TABLE of CONTENTS

Strategic Plan 2020-23 Our People, Our Communities – Healthy Together westernhealth.nl.ca Western Health Strategic Plan 2020-2023 Cover photo by Allan Benoit TABLE OF CONTENTS Meet Western Health’s Board of Trustees 4 Message from the Board Chair 5 Planning Process 6 Western Region Population Health 7 Overview: Western Health by the Numbers 2019-20 8 Lines of Business 10 Values 11 Primary Clients 12 Vision 13 Strategic Issues 14 • Strategic Issue One: Our People 14 • Strategic Issue Two: Quality and Safety 16 • Strategic Issue Three: Innovation 18 Appendix A: Mandate 20 Appendix B: Western Health Regional Map 21 Appendix C: Regional Sites and Contact Information 22 Appendix D: Lines of Business 24 • Promoting Health and Well Being 24 • Preventing Illness and Injury 24 • Providing Supportive Care 24 • Treating Illness and Injury 26 Our People, Our Communities – Healthy Together • Providing Rehabilitative Services 26 • Administering Distinctive Provincial Programs 26 westernhealth.nl.ca Western Health Strategic Plan 2020-2023 Western Health Strategic Plan 2020-2023 3 Meet Western Health’s Board of Trustees Western Health is governed by a voluntary Board of Trustees, each brings their own unique background and experience to help ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality care for our patients, clients, residents, and families within our region. CHAIR Bryson Edwina Marie Doreen WEBB BATEMAN BRENNAN-DOWNEY CHAULK Brian Sonia Keith Mark HUDSON LOVELL WATTON MILLS Lloyd Scott Sheldon Richard WALTERS PORTER PEDDLE PARSONS 4 Western Health Strategic Plan 2020-2023 Message from the Board Chair It is with pleasure I present Western Health’s strategic plan for 2020-23, on behalf of the Board of Trustees. -

Bishop's Charge to Synod 2019

A Special Session of Synod for the Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador “…and the Greatest of these is Love…” (1 Corinthians 13:13, NRSV) St. Thomas’ Church and the Sheraton Hotel Newfoundland St. John’s, September 27-28, 2019 The Bishop’s Charge It is a privilege for me to speak to you today on the occasion of this Special Synod for the Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador. Last night’s Opening Eucharist at St. Thomas’ Church was a stirring celebration as we gathered from across Newfoundland and Labrador to discuss Marriage Equality in our diocese and take counsel for the wellbeing of our church. The theme of this special synod is derived from the 13th Chapter of St. Paul’s 1st Letter to the Corinthians, “…and the Greatest of these is Love…” I acknowledge once more our visitors: The Rt. Rev. John Watton of the Diocese of Central Newfoundland, and Archdeacon David Taylor of the Diocese of Western Newfoundland. I thank you for granting them the privileges of the house. As I have told you previously, the word “synod” comes from a Greek word meaning “assembly” or “meeting.” I also remind you of your responsibility as delegates to consider the whole of our church in the Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador. Although we all come from various places and our decisions are informed by where we come from, now that synod is convened, I ask that your focus be our church as a whole. A diocesan synod of this nature only gathers every year or so and this is the only body of this nature and size that considers the entire church in its deliberations.