Click: the Twelfth Annual Report on Schoolhouse Commercialism Trends: 2008-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Make a Mini Dance

OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Parent Guide Read the “Directions” sheets for step-by-step instructions. SUMMARY In this activity children will watch two very short videos online, then create their own mini dances. WHY This activity will get children thinking about the ways their bodies move. They will think about how movements can represent shapes, such as letters in a word. TIME ■ 10–20 minutes RECOMMENDED AGE GROUP This activity will work best for children in kindergarten through 4th grade. GET READY ■ Read Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring together. Ballet for Martha tells the story of three artists who worked together to make a treasured work of American art. For tips on reading this book together, check out the Guided Reading Activity (http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/pdf/dance/dance_reading.pdf). ■ Read the Step Back in Time sheets. YOU NEED ■ Directions sheets (attached) ■ Ballet for Martha book (optional) ■ Step Back in Time sheets (attached) ■ ThinkAbout sheet (attached) ■ Open space to move ■ Video camera (optional) ■ Computer with Internet and speakers/headphones More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/dance/. OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Directions, page 1 of 2 For adults and kids to follow together. 1. On May 11, 2011, the Internet search company Google celebrated Martha Graham’s birthday with a special “Google Doodle,” which spelled out G-o-o-g-l-e using a dancer’s movements. Take a look at the video (http://www.google.com/logos/2011/ graham.html). -

State Finalist in Doodle 4 Google Contest Is Pine Grove 4Th Grader

Serving the Community of Orcutt, California • July 22, 2009 • www.OrcuttPioneer.com • Circulation 17,000 + State Finalist in Doodle 4 Google Bent Axles Car Show Brings Contest is Pine Grove 4th Grader Rolling History to Old Orcutt “At Google we believe in thinking big What she heard was a phone message and dreaming big, and we can’t think of regarding her achievement. Once the anything more important than encourag- relief at not being in trouble subsided, ing students to do the same.” the excitement set it. This simple statement is the philoso- “It was shocking!” she says, “And also phy behind the annual Doodle 4 Google important. It made me feel known.” contest in which the company invites When asked why she chose to enter the students from all over the country to re- contest, Madison says, “It’s a chance for invent their homepage logo. This year’s children to show their imagination. Last theme was entitled “What I Wish For The year I wasn’t able to enter and I never World”. thought of myself Pine Grove El- as a good draw- ementary School er, but I thought teacher Kelly Va- it would be fun. nAllen thought And I didn’t think this contest was I’d win!” the prefect com- Mrs. VanAllen is plement to what quick to point out s h e i s a l w a y s Madison’s won- trying to instill derful creative in her students side and is clear- – that the world ly proud of her is something not students’ global Bent Axles members display their rolling works of art. -

Activity Pack 1: Imagine

Activity Pack 1: Imagine Activity for Grades 6-8 Thomas Edison once said, “To have a great idea is to have a lot of them.” Brainstorming is a key part of this stage in the creative process. In fact, brainstorming remains one of the most effective creative thinking techniques in use today. The primary cornerstone to brainstorming is the absence of judgment or criticism. All ideas, no matter how non-traditional, have the right to exist at this stage. This is particularly valuable for those students who lack the confidence to publicly share their ideas. A comfortable, collaborative environment can help to inspire students during the “imagine” phase. Invite students to sit on beanbag chairs instead of at desks, in groups instead of by themselves, outdoors rather than inside the school, or listening to music instead of working in silence. This year’s Doodle 4 Google competition theme is: If I could invent one thing to make the world a better place. We can think of no greater purpose for students to show their creativity than to make the world better for others. It all starts with a little imagination! Graffiti Inspiration In this activity, students come up with 101 ideas for improving their schools and use their imaginations and the graffiti carousel brainstorming technique to generate creative ideas for how to make the world a better place. Strategy: This activity uses graffiti carousel brainstorming, a technique used to help generate creative ideas while stimulating physical movement. Large sheets of butcher paper are hung on walls, each with a different prompt or question. -

Expressions of Legislative Sentiment Recognizing

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) Senate Legislative Record One Hundred and Twenty-Sixth Legislature State of Maine Daily Edition First Regular Session December 5, 2012 - July 9, 2013 First Special Session August 29, 2013 Second Regular Session January 8, 2014 - May 1, 2014 First Confirmation Session July 31, 2014 Second Confirmation Session September 30, 2014 pages 1 - 2435 SENATE LEGISLATIVE RECORD Senate Legislative Sentiment Appendix Cheryl DiCara, of Brunswick, on her retirement from the extend our appreciation to Mr. Seitzinger for his commitment to Department of Health and Human Services after 29 years of the citizens of Augusta and congratulate him on his receiving this service. During her career at the department, Ms. DiCara award; (SLS 7) provided direction and leadership for state initiatives concerning The Family Violence Project, of Augusta, which is the the prevention of injury and suicide. She helped to establish recipient of the 2012 Kennebec Valley Chamber of Commerce Maine as a national leader in the effort to prevent youth suicide Community Service Award. The Family Violence Project provides and has been fundamental in uniting public and private entities to support and services for survivors of domestic violence in assist in this important work. We send our appreciation to Ms. Kennebec County and Somerset County. Under the leadership of DiCara for her dedicated service and commitment to and Deborah Shephard, the Family Violence Project each year compassion for the people of Maine, and we extend our handles 4,000 calls and nearly 3,000 face to face visits with congratulations and best wishes to her on her retirement; (SLS 1) victims at its 3 outreach offices and provides 5,000 nights of Wild Oats Bakery and Cafe, of Brunswick, on its being safety for victims at its shelters. -

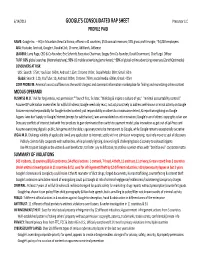

Google's Rap Sheet Consolidated 6-14-13.Xlsx

6/14/2013 GOOGLE'S CONSOLIDATED RAP SHEET Precursor LLC PROFILE PAGE NAME: Google Inc. ‐‐ HQ in Mountain View California; offices in 40 countries; $54b annual revenues; 55% gross profit margin; ~54,000 employees AKA: Youtube, Android, Google+, DoubleClick, Chrome, AdWords, AdSense LEADERS: Larry Page, CEO & Co‐founder; Eric Schmidt, Executive Chairman; Sergey Brin Co‐founder; David Drummond, Chief Legal Officer TURF: 83% global searches (Netmarketshare); 93% US mobile advertising (emarketer); ~50% of global online advertising revenues (ZenithOptimedia) CONSUMERS AT RISK: U.S.: Search: 175m; YouTube: 160m; Android: 135m; Chrome 110m; Social Media: 90m; Gmail: 60m Global: Search: 1.2b; YouTube: 1b; Android: 900m; Chrome: 750m; social media: 600m; Gmail: 425m CORE PROBLEM: America's worst scofflaw runs the world's largest and dominant information marketplace for finding and monetizing online content MODUS OPERANDI BUSINESS M.O. "Ask for forgiveness, not permission;" "launch first, fix later; "think big & inspire a culture of yes;" "minimal accountability controls" Assume ISP safe harbor indemnifies for willful blindness; Google need only react, not act proactively to address well‐known criminal activity on Google Assume minimal responsibility for Google‐hosted content; put responsibility on others to crowdsource detect, & report wrongdoing on Google Argues: laws don't apply to Google/Internet (except for safe harbor); laws are outdated or anti‐innovation; Google's use of others' copyrights is fair use Deny any conflicts of interest; bait with free products to gain dominance then switch to payment model; play innovation as get‐out‐of‐jail‐free card Assume everything digital is public, fair game and sharable; urge everyone to be transparent to Google, while Google remains exceptionally secretive LEGAL M.O. -

Alex Molnar and Faith Boninger Joseph Fogarty

THE EDUCATIONAL COST OF SCHOOLHOUSE COMMERCIALISM Alex Molnar and Faith Boninger University of Colorado Boulder Joseph Fogarty Corballa National School, County Sligo, Ireland November 2011 National Education Policy Center School of Education, University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, CO 80309-0249 Telephone: 303-735-5290 Fax: 303-492-7090 Email: [email protected] http://nepc.colorado.edu The annual report on Schoolhouse Commercialism trends is made possible in part by funding from Consumers Union and is produced by the Commercialism in Education Research Unit Kevin Welner Editor Patricia H. Hinchey Academic Editor William Mathis Managing Director Erik Gunn Managing Editor Briefs published by the National Education Policy Center (NEPC) are blind peer-reviewed by members of the Editorial Review Board. Visit http://nepc.colorado.edu to find all of these briefs. For information on the editorial board and its members, visit: http://nepc.colorado.edu/editorial-board. Publishing Director: Alex Molnar Suggested Citation: Molnar, A., Boninger, F., & Fogarty, J. (2011). The Educational Cost of Schoolhouse Commercialism--The Fourteenth Annual Report on Schoolhouse Commercializing Trends: 2010- 2011. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved [date] from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/schoolhouse-commercialism-2011. This material is provided free of cost to NEPC's readers, who may make non-commercial use of the material as long as NEPC and its author(s) are credited as the source. For inquiries about commercial use, please contact -

Grants and Funding Opportunities

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Grants and Funding Opportunities FUNDING RESOURCES Big List of Educational Grants and Resources Edutopia offers a roundup of educational grants, contests, awards, free toolkits, and classroom guides aimed at helping students, classrooms, schools, and communities. Check the website for weekly updates. http://www.edutopia.org/grants-and-resources EE-Link EE-Link is a project of the North American Association for Environmental Education and a member of the EETAP consortium. The grants section of the website has links for strategies and techniques to develop funding for EE programs, and information on education-related grants that may be applicable to EE providers. The jobs page also hosts jobs and internships. Both can be sorted for ease. http://eelink.net/ Edutopia's Grant Information Page This website from the George Lucas Educational Foundation offers links to corporate, nonprofit, and government grant-making institutions, periodicals with grant information, and more. http://www.edutopia.org/foundation/grant.php Foundation Center The Foundation Center offers information about philanthropy worldwide. Through data, analysis, and training, it connects people who want to change the world to the resources they need to succeed. The center maintains a database on U.S. and global grantmakers and their grants. http://foundationcenter.org/ Foundation Center RFP Bulletin The Foundation Center strengthens the nonprofit sector by advancing knowledge about U.S. philanthropy. The Foundation Center collects, organizes, and communicates information on U.S. philanthropy; conducts and facilitates research on trends in the field; provides education and training on the grantseeking process; and ensures public access to information and services. -

Kvarterakademisk

kvarter Volume 10 • 2015 akademiskacademic quarter Variations of a brand logo Google’s doodles Iben Bredahl Jessen PhD, Associate Professor of Media and Communication at the Department of Communication and Psychology, Aal- borg University. Her research addresses market communi- cation and aesthetics in digital media. Recent publications include articles on cross-media communication (with N. J. Graakjær in Visual Communication, 2013) and online testi- monial advertising (in Advertising & Society Review, 2014). Abstract Provisional changes of the well-known Google logo have been a re- curring phenomenon on the front page of the search engine since 1998. Google calls them “doodles”. The doodles are variations of the Google logo that celebrate famous individuals or cultural events, but the doodles also point to the iconic status of the Google logo as a locus of creativity and reinterpretation. The article explores the icon- ic status of the Google logo as expressed in the doodles. On the basis of a multimodal typographic analysis of a sample of Google’s doodles from 1998 to 2013, the article identifies different types of relations between the well-known Google letters and the new graphic features. The article examines how these relations produce and communicate brand iconicity, and how this iconicity has devel- oped from a typographic perspective. Keywords: doodle, Google, logo, typography, visual identity Introduction A drawing of a stick man behind the logo on Google’s start page on August 30, 1998, marks the beginning of a remarkable semiotic Volume 10 66 Variations of a brand logo kvarter Iben Bredahl Jessen akademiskacademic quarter phenomenon related to the Google logo, the so-called “doodles”. -

2018-19 Administrative Bulletin

2018-19 Administrative Bulletin X-25 3-1-19 1. TECHNOLOGY NEWSLETTER See Enclosure #1 to read the latest technology news! Keith Madsen, ext. 3125 2. BOARD HAPPENINGS See Enclosure #2 to read the board happenings for the month of February! Marilyn Hissong, ext. 1001 3. A MESSAGE FROM THE WELLNESS COACH See Enclosure #3 to read the latest Wellness Tips and information about the upcoming screenings! Tori Bontrager, ext. 1003 4. AUTISM RESOURCE/INFORMATION FAIR The Autism Team is hosting an Autism Resource and Information Fair at the EACS Administration Annex on Saturday, April 13, 2019 from 10:00 am – 2:00 pm ~ See Enclosure #4 for more details. To participate in the Art for Autism Fair see Enclosure #5 for registration details. The deadline has been extended to purchase an Autism t-shirt see Enclosure #6 order form! If you would like to volunteer the day of the event please contact Jen Hartman at ext. 3119. Connie Brown, ext. 3109 5. ANNUAL TRASH-TO-TREASURE ART CONTEST The 21st Annual “Trash-To-Treasure” Art Contest will be held at the Allen County Public Library located at 900 Library Plaza, Fort Wayne, IN on Saturday April 27, 2019 from 9:00am - Noon. This event encourages reuse and recycling. Contest participants will create and display works of art made from 100% recyclable materials. 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place winners will be awarded in each age category with 1st place winners receiving $100, 2nd place winners $50, and 3rd place winners $25. See Enclosure #7 for details. Tamyra Kelly, ext. 1050 6. -

A Secondary Design Curriculum

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 5-2015 Creative Concentrations: A Secondary Design Curriculum Linnea Roberta Gustafson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Education Commons Recommended Citation Gustafson, Linnea Roberta, "Creative Concentrations: A Secondary Design Curriculum" (2015). Master's Theses. 567. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/567 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVE CONCENTRATIONS: A SECONDARY DESIGN CURRICULUM by Linnea Roberta Gustafson A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Art Education Frostic School of Art Western Michigan University May 2015 Thesis Committee: William Charland, Ph.D., Chair Christina Chin, Ph.D. Cat Crotchett, Ph. D. CREATIVE CONCENTRATIONS: A SECONDARY DESIGN CURRICULUM Linnea Roberta Gustafson, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 Design education, as distinct from art education, has been overlooked as an area of student learning, creative expression, and career potential. This thesis explores the benefits of design education for students at the secondary level, when identities are being formed and areas of future study and work are considered. Guided by the newly published National Core Arts Standards, this paper provides a model design curriculum that introduces secondary students to a design-oriented view of the world, explores design principles through real-world applications, and calls attention to professional career options. -

Scholarship Book

SCHOLARSHIP BOOK ELLENSBURG HIGH SCHOOL 2018-2019 CAUTION: This book contains information on scholarships that we knew of that were offered LAST school year (2017-18). Since the future cannot be predicted, this guide will hopefully give you an idea of when scholarships were offered last year, so that you can be looking for them this year. Scholarship information is posted on Facebook at “SCHOLARSHIPS EHS” and on the scholarship board in The Commons. If you have questions, please see Mr. Johansen in the Counseling Office. OTHER SUGGESTED RESOURCES Free Nation-wide Search Tool • www.fastweb.com Free Search Tool for Students from WA • www.WashBoard.org For students from the central WA region • www.WAEF.org 2 FOUR YEAR UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES IN WASHINGTON STATE – PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SCHOLARSHIP INFORMATION Make sure to check each college’s FAFSA priority deadline – each school is different If your college or university is not listed go to their website under financial aid – every college has a website with extensive information. ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY Various scholarships with various deadlines. Please visit their website at: http://www.antiochseattle.edu/futurestudents/aid/scholarships_aus.html BASTYR UNIVERSITY Bastyr University Scholarships for all incoming undergraduate students are a combination of one-time awards, based on need and lower-division academic performance, designed to bridge the cost-resource gap. Students do not need to submit an application to be considered. The awards range from $500 to $3,000, which will be credited to the recipient's tuition during the student's first three quarters. Please visit their website for more information at: http://www.bastyr.edu/admissions/info/finaid.asp?cat=ug&jump=1&sub=1 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Students that apply for and are admitted to Central Washington University by February 1st of their senior year are eligible for merit based tuition waivers for their freshman year. -

General Education Resources

General Education Resources 1) The Problem Site – “A special problem solving site for both students and adults. Here you will find math problems, word games, word puzzles, mystery quests, and many other free educational resources.” http://www.theproblemsite.com/ 2) Articles for Educators – “Provides free lesson plans, classroom activities, field trip ideas, and other resources for teachers.” http://www.articlesforeducators.com/ 3) Tile Puzzler – “An online game which includes several variations on Pentomino puzzles…” http://www.tile-puzzler.com/default.asp 4) Crossword Builder – A utility that allows teachers to create challenging crossword puzzles. Create your own word-hint pairs, or use the built-in math support for math crossword puzzles. http://www.asymptopia.org/AsymptopiaXW_v26/xw.html 5) GCompris – An educational software suite comprising numerous activities for children aged 2 to 10. Some of the activities are game orientated, but still educational. Categories include computer discovery, algebra, science, geography, games, reading, and other. This is actual software. If you would like this installed, please submit a Technology Work Order. 6) TuxTyping – Educational Typing tutor for children. Features several different types of game play, at a variety of difficulty levels. 7) HippoCampus – “Your Free One-Stop Educational Resource” – This site includes resources (course tools, online software, resources, etc) for Algebra, American Government, Biology, Calculus, Environmental Science, Physics, Psychology, and US History, among others. This site also includes many online textbooks!!! An awesome resource for many reasons. http://hippocampus.org/ 8) Owl & Mouse Educational Software – “Free software for learning letters of the alphabet, phonics, letter sounds, reading. Free online US maps, world maps, map of Europe, puzzle maps of the US, Europe, Africa, and Asia.