Carlos Saldanha's Cinematic Reinvention of Rio As an Aspiring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MY KING (MON ROI) a Film by Maïwenn

LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRESOR PRESENTS MY KING (MON ROI) A film by Maïwenn “Bercot is heartbreaking, and Cassel has never been better… it’s clear that Maïwenn has something to say — and a clear, strong style with which to express it.” – Peter Debruge, Variety France / 2015 / Drama, Romance / French 125 min / 2.40:1 / Stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound Opens in New York on August 12 at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas Opens in Los Angeles on August 26 at Laemmle Royal New York Press Contacts: Ryan Werner | Cinetic | (212) 204-7951 | [email protected] Emilie Spiegel | Cinetic | (646) 230-6847 | [email protected] Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman | Shotwell Media | (310) 450-5571 | [email protected] Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | PR & Promotion | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Tony (Emmanuelle Bercot) is admitted to a rehabilitation center after a serious ski accident. Dependent on the medical staff and pain relievers, she takes time to look back on the turbulent ten-year relationship she experienced with Georgio (Vincent Cassel). Why did they love each other? Who is this man whom she loved so deeply? How did she allow herself to submit to this suffocating and destructive passion? For Tony, a difficult process of healing is in front of her, physical work which may finally set her free. LOGLINE Acclaimed auteur Maïwenn’s magnum opus about the real and metaphysical pain endured by a woman (Emmanuelle Bercot) who struggles to leave a destructive co-dependent relationship with a charming, yet extremely self-centered lothario (Vincent Cassel). -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

2006 Promax/Bda Conference Celebrates

2006 PROMAX/BDA CONFERENCE ENRICHES LINEUP WITH FOUR NEW INFLUENTIAL SPEAKERS “Hardball” Host Chris Matthews, “60 Minutes” and CBS News Correspondent Mike Wallace, “Ice Age: The Meltdown” Director Carlos Saldanha and Multi-Dimensional Creative Artist Peter Max Los Angeles, CA – May 9, 2006 – Promax/BDA has announced the addition of four new fascinating industry icons as speakers for its annual New York conference (June 20-22, 2006). Joining the 2006 roster will be host of MSNBC’s “Hardball with Chris Matthews,” Chris Matthews; “60 Minutes” and CBS News correspondent Mike Wallace; director of the current box-office hit “Ice Age: The Meltdown,” Carlos Saldanha, and famed multi- dimensional artist Peter Max. Each of these exceptional individuals will play a special role in furthering the associations’ charge to motivate, inspire and invigorate the creative juices of members. The four newly added speakers join the Promax/BDA’s previously announced keynotes, including author and social activist Dr. Maya Angelou; AOL Broadband's Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Kevin Conroy; Fox Television Stations' President of Station Operations Dennis Swanson; and CNN anchor Anderson Cooper. For a complete list of participants, as well as the 2006 Promax/BDA Conference agenda, visit www.promaxbda.tv. “At every Promax/BDA Conference, we look to secure speakers who are uniquely qualified to enlighten our members with their valuable insights," said Jim Chabin, Promax/BDA President and Chief Executive Officer, in making the announcement. “These four individuals—with their diverse, yet powerful credentials—will undoubtedly shed some invaluable wisdom at the podium.” This year’s Promax/BDA Conference will be held June 20-22 at the New York Marriott Marquis in Times Square and will include a profusion of stimulating seminars, workshops and hands-on demonstrations all designed to enlighten, empower and elevate the professional standings of its members. -

Sarah Mercey Director | Actress | Storyboardist | Animation —————

Sarah Mercey Director | Actress | Storyboardist | Animation ————— FILMOGRAPHY Unannounced | 2021 Feature film, animation Storyboard artist Blue Sky Studios (Fox Animation) — Lucky | 2020 Skydance Animations (Skydance Media) — Nimona | 2020 Feature film, animation Storyboard artist Blue Sky Studios (Fox Animation) — Spies in Disguise | 2017 Feature film, animation Storyboard artist Blue Sky Studios (Fox Animation) — Ferdinand | 2017 Feature film, animation Storyboard artist Blue Sky Studios (Fox Animation) AWARDS Oscar nominee (Academy Awards), Best Animated Feature Film – USA, 2018 2 nominations at the Golden Globes, Best Motion Picture – Animated, Best Original Song – Motion picture, USA, 2018 — Angry Birds | 2016 Feature film, animation Storyboard artist Rovio — Rio 2 | 2014 Feature film Story Blue Sky Studios (Fox Animation) — Magic Hockey Skates | 2012 Holiday special Director, Art Director, Co-Writer Amberwood Entertainment / Canadian Broadcast Corporation AWARD Canadian Screen Award 2014 – Best Direction in an Animated Program or Series & In nomination for Best Animated Series — Ice Age Christmas Special | 2011 Feature film Story Blue Sky Studios (Fox Animation) — Toy Story 3 | 2009 Feature film Character Design Pixar Animation Studios AWARDS Oscar winner (Academy Awards), Best Animated Feature Film of the Year– USA, 2011 Golden Globe winner, Best animated Film of the Year 2011 — WALL-E | 2008 Feature film Animation Pixar Animation Studios AWARDS Oscar winner (Academy Awards), Best Animated Feature Film of the Year– USA, 2009 Golden -

Cinema Em Aula De Língua Estrangeira: Um

Resumo: Este artigo tem como objetivo analisar as CINEMA EM AULA DE LÍNGUA representações do povo brasileiro na animação Rio ESTRANGEIRA: UM ESTUDO A (2011), dirigida por Carlos Saldanha, a partir das discussões desse conceito levadas a cabo por diferentes PARTIR DAS REPRESENTAÇÕES DE linhas teóricas (LUSTOSA, 2013; WITOSLAWSKI, 2005). A partir dessa análise, propomos algumas possibilidades BRASILIDADE NO FILME RIO* de uso desse tipo de discussão como material em aulas de Português como Língua Estrangeira (PLE), sobretudo pensando em questões como a reprodução, propagada CINEMA IN A FOREIGN LANGUAGE pela mídia nacional e internacional, de estereótipos que se referem ao imaginário sobre a identidade brasileira CLASS: A STUDY FROM THE BRAZILIAN pelos alunos desses cursos, ou seja, os possíveis interessados em conhecer a cultura brasileira para REPRESENTATIONS IN THE MOVIE RIO fins ou turísticos, ou acadêmicos, ou, não incomum, profissionais. Diogo Simão 1 Palavras-chave: Cinema. Ensino. Línguas Estrangeiras Júlio Cezar Marques da Silva 2 Modernas. Brasilidade. Abstract: This article aims to analyze the representations of the Brazilian people in the animation Rio (2011), directed by Carlos Saldanha, from the discussions of this concept carried out by different theoretical lines (LUSTOSA, 2013; WITOSLAWSKI, 2005). From this analysis, we propose some possibilities of using this type of discussion as material in Portuguese as a Foreign Language (PLE) classes, especially thinking about issues such as the reproduction, propagated by national and international media, of stereotypes that refer to the imaginary about the Brazilian identity by the students of these courses, that is, those interested in knowing Brazilian culture for tourism or academic purposes, or, not uncommonly, professionals. -

Imaginário, Cinema E Turismo: Uma Viagem Por Clichês Culturais Associados Ao Brasil, No Filme Rio 2

Rosa dos Ventos ISSN: 2178-9061 [email protected] Universidade de Caxias do Sul Brasil Imaginário, Cinema e Turismo: Uma Viagem por Clichês Culturais Associados ao Brasil, no Filme Rio 2 LOPES, RAFAEL DE FIGUEIREDO; NOGUEIRA, WILSON DE SOUZA; BAPTISTA, MARIA LUIZA CARDINALE Imaginário, Cinema e Turismo: Uma Viagem por Clichês Culturais Associados ao Brasil, no Filme Rio 2 Rosa dos Ventos, vol. 9, núm. 3, 2017 Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Brasil Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=473552033016 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18226/21789061.v9i3p377 PDF gerado a partir de XML Redalyc JATS4R Sem fins lucrativos acadêmica projeto, desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa acesso aberto RAFAEL DE FIGUEIREDO LOPES, et al. Imaginário, Cinema e Turismo: Uma Viagem por Clichês Culturais ... Artigos Imaginário, Cinema e Turismo: Uma Viagem por Clichês Culturais Associados ao Brasil, no Filme Rio 2 Imaginary, Movies and Tourism: A Travel trough Cultural Stereotypes Associated with Brazil in the Movie Rio 2 RAFAEL DE FIGUEIREDO LOPES DOI: https://doi.org/10.18226/21789061.v9i3p377 Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Brasil Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? rafafl[email protected] id=473552033016 WILSON DE SOUZA NOGUEIRA Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Brasil [email protected] MARIA LUIZA CARDINALE BAPTISTA Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Brasil [email protected] Recepção: 02 Setembro 2016 Aprovação: 23 Junho 2017 Resumo: O artigo busca refletir acerca de clichês associados ao imaginário sobre o Brasil, especialmente, ao Rio de Janeiro e à Amazônia, a partir de cenas do filme de animação Rio2 (Carlos Saldanha, 2014). -

A Amazônia Animada: Uma Análise Pós-Colonialista Do Filme Rio 2 the Animated Amazon Forest: a Postcolonial Analysis of the Movie Rio 2

A Amazônia animada: uma análise pós-colonialista do filme Rio 2 The animated Amazon forest: a postcolonial analysis of the movie Rio 2 Luciana Maira de Sales Pereira1 Resumo: A Amazônia é constantemente representada nas produções cinematográficas nacionais e internacionais. Entretanto, sua representação sígnica audiovisual é construída a partir do olhar, da cultura e da ideologia de quem a descreve. Considerando a animação fílmica Rio 2, de Carlos Saldanha, um artefato cultural que apresenta um dado discurso sobre a Floresta Amazônica, este artigo tem por objetivo analisar de que modo a produção discursiva, verbal e imagética, da animação reproduz imagens estereotipadas sobre a região amazônica. Palavras-chave: Amazônia; Cinema; Animação; Colonialismo. Abstract: The Amazon is constantly represented in national and international cinematographic productions. However, its audiovisual representation is based on the viewpoint, culture and ideology of the person who describes it. Considering the film animation Rio 2, by Carlos Saldanha, a cultural artifact that presents a discourse about the Amazon Rainforest, this article aims to analyze how the verbal and imaginary discursive production of Saldanha’s animation reproduces stereotyped images about the Amazon region. Keywords: Amazon; Cinema; Animation; Colonialism. Introdução Desde os primórdios da descoberta do Brasil, dada sua magnitude, diversidade de fauna e flora, o contorno e a extensão de seus rios, a Amazônia tem sido objeto de estudo e admiração para muitos historiadores, cientistas, escritores e cineastas. Por esse motivo, a grande floresta tropical localizada na região Norte do Brasil não é apenas um importante bioma, mas uma grande construção cultural e simbólica, representada inúmeras vezes por diversos signos, linguísticos e visuais, entre eles relatórios de viagens, obras literárias, pinturas e filmes2, transitando entre o real e o imaginário. -

9781474410571 Contemporary

CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd i 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Traditions in American Cinema Series Editors Linda Badley and R. Barton Palmer Titles in the series include: The ‘War on Terror’ and American Film: 9/11 Frames Per Second Terence McSweeney American Postfeminist Cinema: Women, Romance and Contemporary Culture Michele Schreiber In Secrecy’s Shadow: The OSS and CIA in Hollywood Cinema 1941–1979 Simon Willmetts Indie Reframed: Women’s Filmmaking and Contemporary American Independent Cinema Linda Badley, Claire Perkins and Michele Schreiber (eds) Vampires, Race and Transnational Hollywoods Dale Hudson Who’s in the Money? The Great Depression Musicals and Hollywood’s New Deal Harvey G. Cohen Engaging Dialogue: Cinematic Verbalism in American Independent Cinema Jennifer O’Meara Cold War Film Genres Homer B. Pettey (ed.) The Style of Sleaze: The American Exploitation Film, 1959–1977 Calum Waddell The Franchise Era: Managing Media in the Digital Economy James Fleury, Bryan Hikari Hartzheim, and Stephen Mamber (eds) The Stillness of Solitude: Romanticism and Contemporary American Independent Film Michelle Devereaux The Other Hollywood Renaissance Dominic Lennard, R. Barton Palmer and Murray Pomerance (eds) Contemporary Hollywood Animation: Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown www.edinburghuniversitypress.com/series/tiac 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiiiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. -

Show Your Community That You Appreciate Them by Hosting a Movie Night That’S Fun for the Whole Family

2016 FAMILY FRIENDLY MOVIE CATALOGUE Show your community that you appreciate them by hosting a movie night that’s fun for the whole family.. It’s as easy as 1- 2 - 3! www.criterionpic.com YOUR COMPLETE MOVIE LICENSING COMPANY FOR YOUR MOVIE SCREENINGS! Criterion Pictures is one of the largest non-theatrical providers of feature films in North America. In Canada, we have exclusive relationships with some of Hollywood’s largest film studios and licence their movies for public screenings. We offer a variety of licensing rights, in order to provide tailored programming options to maximize the suc- cess of your event. Whether you’re showing a movie for camps, an after school program or even a birthday party, we have a large catalogue of family friendly films. Whatever your budget, we can help make your next movie night a big success! WE HAVE EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO MAKE YOUR PROGRAM A SUCCESS From the best selection of box office hits, animated movies and family classics, we licence exclusive movies from 20th Century Fox, Fox Searchlight, Warner Brothers, Paramount Pictures, DreamWorks and Entertainment One and more... We proudly offer our titles ahead of the DVD date and our entire catalogue is available all year long, which means no summer black-out dates! AN EXPERIENCED SALES & SERVICE TEAM THAT’S JUST ONE PHONE CALL AWAY We work with our customers to deliver content by all available means and strive to meet their individual needs. Contact us today for more information! We also offer a large collection of socially conscious films. -

Programming Ideas

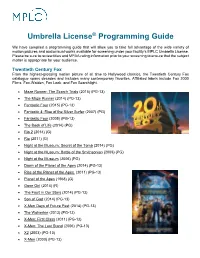

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013)