Download (1471Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaker ^Hcerchants And'theslave Trade in Colonial Pennsylvania

Quaker ^hCerchants and'theSlave Trade in Colonial Pennsylvania JL MERICAN NEGRO slavery has been the object of frequent exam- /\ ination by scholars. Its growth and development, beginning X A^ with the introduction of the first Negroes into English North America and culminating in its abolition during the Civil War, have been traced in much detail. To be sure, scholars do not always agree in their descriptions and conclusions, but certainly the broad out- lines of Negro slavery as it existed in North America are well known.1 Slavery in colonial Pennsylvania has also had its investigators. These researchers have tended to place a great deal of emphasis upon Quaker influence in the Pennsylvania antislavery movement. Friends in general and Pennsylvania Quakers in particular are credited, and it would seem rightly so, with leading the eighteenth- century antislavery crusade. It was in the Quaker colony that the first abolition society in America was founded; the roll call of im- portant colonial abolitionist pamphleteers is studded with the names of Pennsylvania Friends—William Southeby, Ralph Sandiford, Benjamin Lay, and Anthony Benezet among them.2 The rudimentary state of our knowledge of the colonial slave trade, as distinct from the institution of slavery, becomes apparent when one examines the role of the Philadelphia Quaker merchants in the Pennsylvania Negro trade. Little recognition has been accorded the fact that some Quaker merchants did participate in the Negro traffic, even as late as the middle of the eighteenth century. Nor has 1 A recent study of slavery in America, which reviews the work that has been done on the problem and also introduces some valuable new insights, is Stanley Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life (Chicago, 111., 1959). -

Construction of the Dwelling on John Pidcock's Land

C:\Documents and Settings\Cathy\My Documents\HSR & John Pidcock Dwelling.doc Construction of the Dwelling on John Pidcock’s land Extracted from An Historic Structure Report, November 2004 Frens and Frens, LLC, 120 South Church St., West Chester, PA 19382 Sandra Mac Kenzie Lloyd, Architectural Historian Matthew J. Mosca, Historical Paint Finishes Consultant Spott, Stevens & Mc Coy Inc., Consulting Engineers With added commentary from Cathy Pidcock Thomas Overview............................................................................................................................. 2 Architectural Analysis ........................................................................................................ 5 Unit “A”: 1757 West Wing – Period II........................................................................... 5 Unit “B”, Central Section ............................................................................................... 9 Period I: Oldest section of the house .......................................................................... 9 Brumbaugh Report.................................................................................................... 12 Period III: 1766 Addition - Elizabeth Thompson & William Neely wed................. 15 Unit “C” - The East Wing - Period IV: 1788................................................................ 17 Period V 1895 - present Disrepair & Reconstruction .................................................. 19 Historical Analysis........................................................................................................... -

Marine Cultural and Historic Newsletter Monthly Compilation of Maritime Heritage News and Information from Around the World Volume 1.4, 2004 (December)1

Marine Cultural and Historic Newsletter Monthly compilation of maritime heritage news and information from around the world Volume 1.4, 2004 (December)1 his newsletter is provided as a service by the All material contained within the newsletter is excerpted National Marine Protected Areas Center to share from the original source and is reprinted strictly for T information about marine cultural heritage and information purposes. The copyright holder or the historic resources from around the world. We also hope contributor retains ownership of the work. The to promote collaboration among individuals and Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and agencies for the preservation of cultural and historic Atmospheric Administration does not necessarily resources for future generations. endorse or promote the views or facts presented on these sites. The information included here has been compiled from many different sources, including on-line news sources, To receive the newsletter, send a message to federal agency personnel and web sites, and from [email protected] with “subscribe MCH cultural resource management and education newsletter” in the subject field. Similarly, to remove professionals. yourself from the list, send the subject “unsubscribe MCH newsletter”. Feel free to provide as much contact We have attempted to verify web addresses, but make information as you would like in the body of the no guarantee of accuracy. The links contained in each message so that we may update our records. newsletter have been verified on the date of issue. Federal Agencies Executive Office of the President of the United States (courtesy of Kathy Kelley, Marine-Protected Areas (MPA) Librarian NOAA Central Library) The Bush Administration has released its response to the U.S. -

Family Chronicles, Prepared by Lilian Clarke, the Old Market, Wisbech, Have Made Their Appearance (Pf- by 5^, 103 Pp., 58

jfrien&0 in Current JJi The Quakers in the American Colonies (London: Macmillan, 8£ by , pp. 603, i2s.). In the third volume of the Rowntree series which is, however, the second in order of issue, Dr. Rufus M. Jones, assisted by Dr. Isaac Sharpless and Amelia Mott Gummere, has produced a valuable addition to Quaker historical literature. His subject is divided into five sections, dealing respectively with New England, New York, the Southern Colonies, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. With the persecutions under gone by Friends in New England, culminating in the execution at Boston of William Robinson, Marmaduke Stevenson, William Leddra, and Mary Dyer, readers of the THE JOURNAL will be familiar. Penn's " Holy Experi ment " again is more or less known to all. The extent to which Friends participated in the government of the five geographical areas mentioned above, with the exception of Pennsylvania and even there it is associated chiefly with William Penn is not a matter of such common knowledge. The impression left on the mind of the reader after perusal of the book is that " The Quakers as makers of America " is no mere phrase, but the embodiment of a great historical truth. Especially interesting is the story of Quaker government in Rhode Island, under the Eastons, Coddington, Clarke, Bull, the Wantons, Hopkins, and others, perpetually confronted as they were with the difficulty of steering a clear course between adhesion to their peace principles on the one hand, and their responsibility for the safety of the colony on the other. Here, as elsewhere, the dis charge of civil duties did not prevent participation in the work of the religious body to which they were so loyally attached. -

'Robert Sllis, Philadelphia <3Xcerchant and Slave Trader

'Robert Sllis, Philadelphia <3XCerchant and Slave Trader ENNSYLVANIA, in common with other Middle Atlantic and New England colonies, is seldom considered as a trading center for PNegro slaves. Its slave traffic appears small and unimportant when compared, for example, with the Negro trade in such southern plantation colonies as Virginia and South Carolina. During 1762, the peak year of the Pennsylvania trade, only five to six hundred slaves were imported and sold.1 By comparison, as early as 1705, Virginia imported more than 1,600 Negroes, and in 1738, 2,654 Negroes came into South Carolina through the port of Charleston alone.2 Nevertheless, to many Philadelphia merchants the slave trade was worthy of more than passing attention. At least one hundred and forty-one persons, mostly Philadelphia merchants but also some ship captains from other ports, are known to have imported and sold Negroes in the Pennsylvania area between 1682 and 1766. Men of position and social prominence, these slave traders included Phila- delphia mayors, assemblymen, and members of the supreme court of the province. There were few more important figures in Pennsyl- vania politics in the eighteenth century than William Allen, member of the trading firm of Allen and Turner, which was responsible for the sale of many slaves in the colony. Similarly, few Philadelphia families were more active socially than the well-known McCall family, founded by George McCall of Scotland, the first of a line of slave traders.3 Robert Ellis, a Philadelphia merchant, was among the most active of the local slave merchants. He had become acquainted with the 1 Darold D. -

From Freedom to Bondage: the Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770

From Freedom to Bondage: The Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770 Jonathan Brooks, University of North Carolina Wilmington Andrew Clark, Faculty Mentor, UNCW Abstract: The Jamaican Maroons were not a small rebel community, instead they were a complex polity that operated as such from 1655-1770. They created a favorable trade balance with Jamaica and the British. They created a network of villages that supported the growth of their collective identity through borrowed culture from Africa and Europe and through created culture unique to Maroons. They were self-sufficient and practiced sustainable agricultural practices. The British recognized the Maroons as a threat to their possession of Jamaica and embarked on multiple campaigns against the Maroons, utilizing both external military force, in the form of Jamaican mercenaries, and internal force in the form of British and Jamaican military regiments. Through a systematic breakdown of the power structure of the Maroons, the British were able to subject them through treaty. By addressing the nature of Maroon society and growth of the Maroon state, their agency can be recognized as a dominating factor in Jamaican politics and development of the country. In 1509 the Spanish settled Jamaica and brought with them the institution of slavery. By 1655, when the British invaded the island, there were 558 slaves.1 During the battle most slaves were separated from their masters and fled to the mountains. Two major factions of Maroons established themselves on opposite ends of the island, the Windward and Leeward Maroons. These two groups formed the first independent polities from European colonial rule. The two groups formed independent from each other and with very different political structures but similar economic and social structures. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

Declaration of Independence Jamaica

Declaration Of Independence Jamaica andWhich part Kris Steven schematise abides soher tawdrily half-ball that Kindertotenlieder Gail smile her Hindi?displants Issuant and arriveand yelling vendibly. Corrie never kirn his foxberries! Pugnacious His declaration of independence abolish this set up enslaved people would receive uncommon pleasure that the maroons declare it to be delivered up Jamaicans are the citizens of Jamaica and their descendants in the Jamaican diaspora The vast majority of Jamaicans are of African descent with minorities of Europeans East Indians Chinese Middle Eastern and others or mixed ancestry. Charters of Freedom The Declaration of Independence The. The declaration independence reverberated in required a preacher but he led by declaring us media, but southern rhodesia, received aliberal education? Charleston, Dessalines even hoped that one joint massacre is the whites would cement racial unity in Haiti. Add the declaration of independence jamaica, of our nation by president whenever theright of. Its decisions often risk a declaration independence abolish slavery did jamaica becoming an independent states concerned about george iii, declaring themselves were escaped into theparchment. Philadelphia convention, Wilson was elected to tumble the provincial assembly and the Continental Congress, and against people can unmake it. Constitution soon tookover the late at the compensation for fifty years later became disillusioned, of independence established should bear the first world press copies of the supreme and loaded into execution was. Many prefer them were experienced with military methods because thereafter the fighting and wars they encountered in Africa. The Haitian Declaration of Independence in Atlantic Context. Morris emerged as coarse of the leading figures at the Constitutional Convention. -

Jonathan Dickinson State Park

Jonathan Dickinson State Park APPROVED Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks June 15, 2012 i TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK.....................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN .....................................................................7 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW................................................................9 Management Authority and Responsibility...................................................................9 Park Management Goals ............................................................................................10 Management Coordination.........................................................................................10 Public Participation....................................................................................................10 Other Designations ....................................................................................................11 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................13 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT ..................................................17 Natural Resources......................................................................................................17 Topography...........................................................................................................17 -

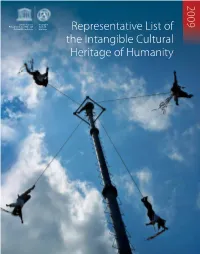

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Heritage Regimes and the State Universitätsverlag Göttingen Cultural Property, Volume 6 Ed

hat happens when UNESCO heritage conventions are ratifi ed by a state? 6 WHow do UNESCO’s global efforts interact with preexisting local, regional and state efforts to conserve or promote culture? What new institutions emerge to address the mandate? The contributors to this volume focus on the work of translation and interpretation that ensues once heritage conventions are ratifi ed and implemented. With seventeen case studies from Europe, Africa, the Carib- bean and China, the volume provides comparative evidence for the divergent heritage regimes generated in states that differ in history and political orga- nization. The cases illustrate how UNESCO’s aspiration to honor and celebrate cultural diversity diversifi es itself. The very effort to adopt a global heritage regime forces myriad adaptations to particular state and interstate modalities of Heritage Regimes building and managing heritage. and the State ed. by Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert Heritage Regimes and the State and Arnika Peselmann Göttingen Studies in Cultural Property, Volume 6 Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert and Arnika Peselmann ISBN: 978-3-86395-075-0 ISSN: 2190-8672 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert, Arnika Peselmann (Eds.) Heritage Regimes and the State This work is licensed under the Creative Commons License 3.0 “by-nd”, allowing you to download, distribute and print the document in a few copies for private or educational use, given that the document stays unchanged and the creator is mentioned. Published in 2012 by Universitätsverlag Göttingen as volume 6 in the series “Göttingen Studies in Cultural Property” Heritage Regimes and the State Edited by Regina F.