Racism and Extremism Monitor Eight Report Edited by Jaap Van Donselaar and Peter R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200227 Liberation Of

THE LIBERATION OF OSS Leo van den Bergh, sitting on a pile of 155 mm grenades. Photo: City Archives Oss 1 September 2019, Oss 75 Years of Freedom The Liberation of Oss Oss, 01-09-2019 Copyright Arno van Orsouw 2019, Oss 75 Years of Freedom, the Liberation of Oss © 2019, Arno van Orsouw Research on city walks around 75 years of freedom in the centre of Oss. These walks have been developed by Arno van Orsouw at the request of City Archives Oss. Raadhuislaan 10, 5341 GM Oss T +31 (0) 0412 842010 Email: [email protected] Translation checked by: Norah Macey and Jos van den Bergh, Canada. ISBN: XX XXX XXXX X NUR: 689 All rights reserved. Subject to exceptions provided by law, nothing from this publication may be reproduced and / or made public without the prior written permission of the publisher who has been authorized by the author to the exclusion of everyone else. 2 Foreword Liberation. You can be freed from all kinds of things; usually it will be a relief. Being freed from war is of a different order of magnitude. In the case of the Second World War, it meant that the people of Oss had to live under the German occupation for more than four years. It also meant that there were men and women who worked for the liberation. Allied forces, members of the resistance and other groups; it was not without risk and they could lose their lives from it. During the liberation of Oss, on September 19, 1944, Sergeant L.W.M. -

Quarterly Aviation Report

Quarterly Aviation Report DUTCH SAFETY BOARD page 14 Investigations Within the Aviation sector, the Dutch Safety Board is required by law to investigate occurrences involving aircraft on or above Dutch territory. In addition, the Board has a statutory duty to investigate occurrences involving Dutch aircraft over open sea. Its October - December 2020 investigations are conducted in accordance with the Safety Board Kingdom Act and Regulation (EU) In this quarterly report, the Dutch Safety Board gives a brief review of the no. 996/2010 of the European past year. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of commercial Parliament and of the Council of flights in the Netherlands was 52% lower than in 2019. The Dutch Safety 20 October 2010 on the Board therefore received fewer reports. In 2020, 27 investigations were investigation and prevention of started into serious incidents and accidents in the Netherlands. In addition, accidents and incidents in civil the Dutch Safety Board opened an investigation into a serious incident aviation. If a description of the involving a Boeing 747 in Zimbabwe in 2019. The Civil Aviation Authority page 7 events is sufficient to learn of Zimbabwe has delegated the entire conduct of the investigation to the lessons, the Board does not Netherlands, where the aircraft is registered and the airline is located. In the conduct any further investigation. past year, the Dutch Safety Board has offered and/or provided assistance to foreign investigative bodies thirteen times in investigations involving Dutch The Board’s activities are mainly involvement. aimed at preventing occurrences in the future or limiting their In this quarterly report you can read, among other things, about an consequences. -

Ecre Country Report 2005

European Council on Refugees and Exiles - Country Report 2005 ECRE COUNTRY REPORT 2005 This report is based on the country reports submitted by member agencies to the ECRE Secretariat between June and August 2005. The reports have been edited to facilitate comparisons between countries, but no substantial changes have been made to their content as reported by the agencies involved. The reports are preceded by a synthesis that is intended to provide a summary of the major points raised by the member agencies, and to indicate some of the common themes that emerge from them. It also includes statistical tables illustrating trends across Europe. ECRE would like to thank all the member agencies involved for their assistance in producing this report. The ECRE country report 2005 was compiled by Jess Bowring and edited by Carolyn Baker. 1 European Council on Refugees and Exiles - Country Report 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Austria..........................................................................................................................38 Belgium........................................................................................................................53 Bulgaria........................................................................................................................64 Czech Republic ............................................................................................................74 Denmark.......................................................................................................................84 -

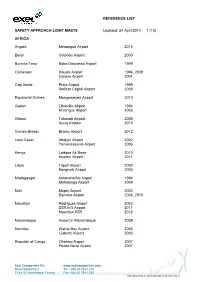

Reference List Safety Approach Light Masts

REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 1 (10) AFRICA Angola Menongue Airport 2013 Benin Cotonou Airport 2000 Burkina Faso Bobo Diaulasso Airport 1999 Cameroon Douala Airport 1994, 2009 Garoua Airport 2001 Cap Verde Praia Airport 1999 Amilcar Capral Airport 2008 Equatorial Guinea Mongomeyen Airport 2010 Gabon Libreville Airport 1994 M’vengue Airport 2003 Ghana Takoradi Airport 2008 Accra Kotoka 2013 Guinea-Bissau Bissau Airport 2012 Ivory Coast Abidjan Airport 2002 Yamoussoukro Airport 2006 Kenya Laikipia Air Base 2010 Kisumu Airport 2011 Libya Tripoli Airport 2002 Benghazi Airport 2005 Madagasgar Antananarivo Airport 1994 Mahajanga Airport 2009 Mali Moptu Airport 2002 Bamako Airport 2004, 2010 Mauritius Rodrigues Airport 2002 SSR Int’l Airport 2011 Mauritius SSR 2012 Mozambique Airport in Mozambique 2008 Namibia Walvis Bay Airport 2005 Lüderitz Airport 2005 Republic of Congo Ollombo Airport 2007 Pointe Noire Airport 2007 Exel Composites Plc www.exelcomposites.com Muovilaaksontie 2 Tel. +358 20 754 1200 FI-82110 Heinävaara, Finland Fax +358 20 754 1330 This information is confidential unless otherwise stated REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 2 (10) Brazzaville Airport 2008, 2010, 2013 Rwanda Kigali-Kamombe International Airport 2004 South Africa Kruger Mpumalanga Airport 2002 King Shaka Airport, Durban 2009 Lanseria Int’l Airport 2013 St. Helena Airport 2013 Sudan Merowe Airport 2007 Tansania Dar Es Salaam Airport 2009 Tunisia Tunis–Carthage International Airport 2011 ASIA China -

What Happens Next? Life in the Post-American World JANUARY 2014 VOL

Will mankind ARMED, DANGEROUS The reason New ‘solution’ to ever reach Europe has a lot more for world family problems: the stars? nukes than you think troubles Don’t have kids THE PHILADELPHIA TRUMPETJANUARY 2014 | thetrumpet.com What Happens Next? Life in the post-American world JANUARY 2014 VOL. 25, NO. 1 CIRC. 325,015 THE DANGER ZONE T A member of the German Air Force based in Alamogordo, New Mexico, prepares a Tornado aircraft for takeoff. How naive is America to entrust this immense firepower to nations that so recently—and throughout history— have proved to be enemies of the free world. WORLD COVER SOCIETY 1 FROM THE EDITOR Europe’s 20 How Did Family Get Nuclear Secret 2 What Happens After So Complicated? 18 INFOGRAPHIC American B61 a Superpower Dies? 34 SOCIETYWATCH Thermonuclear Weapons in The world is about to find out. Europe SCIENCE 23 Will Mankind Ever Reach 26 WORLDWATCH Unifying 7 Conquering the Holy Land the Stars? Europe’s military—through The cradle of civilization, the stage of the Crusades, the most contested the back door • North Africa’s territory on Earth—who will gain control now that America is gone? policeman • Is the president BIBLE purging the military of 31 PRINCIPLES OF LIVING 10 dissenters • Don’t underrate The World’s Next Superpower Mankind’s Aversion Therapy 12 Partnering with Latin America al Shabaab • No prize for you • Lesson 13 Africa’s powerful neighbor Moscow puts Soviet squeeze 35 COMMENTARY A Warning on neighbor nations of Hope 14 Czars and Emperors COVER If the U.S. -

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party. -

Woods Was Considering Nationalization Fortis Already for the Summer

[Unofficial Translation of Article] De Standaard, Bos wou Fortis Nederland voor de zomer al kopen, 10/12/2008 (Translated). http://www.standaard.be/cnt/cv23r142 Woods was considering nationalization Fortis already for the summer By Finance Minister Wouter Bos had considered the idea for summer to nationalize Fortis. That he says this week in Smoking Netherlands. ' For the summer and I found that with Fortis Nout Wellink did not go well. That tension could arise between the interests of Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and the top of the group. And that we should act very quickly in a situation like this. When I have the option already considered that the State could take over the Dutch part of Fortis. I have always thought: if it is necessary, then we do it. ' The pronunciation of forest comes as a surprise. Until now it was believed that the idea of nationalising the bank only at the end of september, just before the takeover. ' Jan Peter is a very good negotiator ' In the interview in the winter issue of Netherlands Wouter Bos also looks back on the Free negotiations on the nationalization of Fortis and ABN Amro. Wouter Bos and Prime Minister Balkenende, previously at two Cabinet formations as rivals were sitting opposite each other, now had to defend the Dutch interest in unison. ' I have at one point against Jan Peter said: you have to use all the tricks that you have in the formation used against me. ' According to woodland can protest loudly Balkende in negotiations: ' if the opposing team says something where he did not agree, he literally sitting briesen and puffing and say it's all nothing is. -

United States Nuclear Weapons in Europe

United States nuclear CND weapons in Europe Around 200 United States nuclear B61 free-fall gravity bombs are stationed in five countries in Europe: Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and Turkey. While the governments of these countries have never officially declared the presence of these G weapons, individuals such as the former Italian president and former Dutch prime minister have confirmed this to be the case. HE nuclear sharing arrangement is part of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Articles 1 and 2 of N North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) the NPT forbid the transfer of nuclear weapons to T defence policy. In peace time, the nuclear non-nuclear weapon states, but Belgium, Germany, the weapons stored in non-nuclear countries are guarded Netherlands, Italy and Turkey are all non-nuclear. I by US forces, with a dual code system activated in a time of war. Both host country and the US would Even though the UK does not host US bombs any then need to approve the use of the weapons, which more, the UK’s nuclear weapons system has been F would be launched on the former’s airplanes. assigned to NATO since the 1960s. Ultimately, this means that the UK’s nuclear weapons could be used When these bombs were initially deployed, the original against a country attacking (or threatening to attack) targets were eastern European states. But as the Cold one of the alliance member states since an attack on War ended, and these states became part of the one NATO member state is seen as being an attack on E European Union and in some cases NATO itself, the all member states. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

U:\Wp51\Wp51\Marloes\Voor De Uitgever\Deel 1.Wpd

Hate Speech Revisited SCHOOL OF HUMAN RIGHTS RESEARCH SERIES, Volume 45 A commercial edition of this dissertation will be published by Intersentia under ISBN 978-1-78068-032-3 The titles published in this series are listed at the end of this volume Cover illustration © Nur Acar Tangün (2006), www.nuracartangun.com Typesetting: Wieneke Matthijsse, Willem Pompe Institute for Criminal Law and Criminology, Utrecht University Hate Speech Revisited A comparative and historical perspective on hate speech law in the Netherlands and England & Wales Haatuitingen heroverwogen. Een vergelijkend en historisch perspectief op het recht over haatuitingen in Nederland en Engeland & Wales (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 16 december 2011 des middags te 2.30 uur door Lucia Adriana van Noorloos geboren op 8 februari 1983 te Raamsdonk Promotoren: Prof. dr. C.H. Brants-Langeraar Prof. dr. J.E. Goldschmidt ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Four years ago my attention was drawn to an advertisement for a Ph.D. researcher on the implications of countering discrimination and radicalisation through criminal law on hate speech, a subject matter so fascinating that I just had to apply for this position. Now, four years later, I can only say that the topic has never failed to intrigue me and a quick look at the Dutch newspapers in the past year shows that I am not the only one intrigued by it. -

De Digitale Schandpaal De Invloed Van Internet Op Het Verloop Van Affaires En Schandalen

118 | Peter L. M. Vasterman* De digitale schandpaal De invloed van internet op het verloop van affaires en schandalen ‘De geschiedenis van het schandaal is dus een onderdeel van de geschiedenis van de openbaarheid.’ (De Swaan, 1996: 28). Door de opkomst van internet is het schandaal niet meer exclusief het domein van de professionele media. Aan de hand van vier actuele cases (Demmink, Depla, Duyvendak en Herfkens) is de invloed onderzocht van diverse types websites op de verschillende stadia waarin een affaire zich ontwikkelt tot schandaal. Vooral de interactie tussen de semipro- fessionele blogs en de nieuwsmedia is van belang, de rol van de inter- netgebruiker beperkt zich tot het (verontwaardigd) reageren op de ont- hullingen. Inleiding In 17 januari 1998 maakt Matt Drudge op zijn weblog Drudge Report 1 bekend dat Newsweek op het laatste moment heeft afgezien van publicatie van een onthulling over president Clinton, die een verhouding zou hebben met een stagiaire in het Witte Huis. Newsweek wil eerst nog meer feiten verifiëren, maar voor Drudge is dat geen reden om niet meteen te publiceren (Bosscher, 2007: 104). Als het verhaal eenmaal op straat ligt, kunnen de andere media niet achterblijven en binnen de kortste keren is het Lewinsky-schandaal een feit (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 1999: 13). Met één klap wordt duidelijk dat internet de spelregels heeft veranderd en dat ook een relatief onbekende eenmanssite met roddel- en shownieuws in staat is een schandaal te lanceren. Een kleine tien jaar later, eind november 2007 raakt de Nijmeegse wethouder Paul Depla in opspraak na onthullingen op weblog Geenstijl.nl2 dat beveiligingscamera’s * Dr. -

Peter Weiss. Andrei Platonov. Ragnvald Blix. Georg Henrik Von Wright. Adam Michnik

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. March 2011. Vol IV:1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Södertörn University, Stockholm FEATURE. Steklov – Russian BALTIC temple of pure thought W O Rbalticworlds.com L D S COPING WITH TRANSITIONS PETER WEISS. ANDREI PLATONOV. RAGNVALD BLIX. GEORG HENRIK VON WRIGHT. ADAM MICHNIK. SLAVENKA DRAKULIĆ. Sixty pages BETRAYED GDR REVOLUTION? / EVERYDAY BELARUS / WAVE OF RELIGION IN ALBANIA / RUSSIAN FINANCIAL MARKETS 2short takes Memory and manipulation. Transliteration. Is anyone’s suffering more important than anyone else’s? Art and science – and then some “IF YOU WANT TO START a war, call me. Transliteration is both art and science CH I know all about how it's done”, says – and, in many cases, politics. Whether MÄ author Slavenka Drakulić with a touch царь should be written as tsar, tzar, ANNA of gallows humor during “Memory and czar, or csar may not be a particu- : H Manipulation: Religion as Politics in the larly sensitive political matter today, HOTO Balkans”, a symposium held in Lund, but the question of the transliteration P Sweden, on December 2, 2010. of the name of the current president This issue of the journal includes a of Belarus is exceedingly delicate. contribution from Drakulić (pp. 55–57) First, and perhaps most important: in which she claims that top-down gov- which name? Both the Belarusian ernance, which started the war, is also Аляксандр Лукашэнка, and the Rus- the path to reconciliation in the region. sian Александр Лукашенко are in use. Balkan experts attending the sympo- (And, while we’re at it, should that be sium agree that the war was directed Belarusian, or Belarussian, or Belaru- from the top, and that “top-down” is san, or Byelorussian, or Belorussian?) the key to understanding how the war BW does not want to take a stand on began in the region.