The Works for Clarinet Commissioned by the Concours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) The Concertizing Clarinet in the Music of the 20th- 21st Centuries Yu Zhao Department of Musical Upbringing and Education Institute of Music, Theatre and Choreography Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The article deals with stating the problem of a clarinet concert of the 20-21 centuries (one should note in research in ontology of the genre of Clarinet Concert in 20-21 this regard S. E. Artemyev‟s full-featured thesis considering centuries. The author identifies genre variants of long forms the Concerto for clarinet and orchestra of the 18th century). for solo clarinet with orchestra or instrumental ensemble and proposes further steps in making such a research, as well. II. A SHORT GUIDE IN THE HISTORY OF THE CLARINET Keywords—instrumental concert; concertizing; concerto; CONCERT GENRE concert genres; genre diversity Studies in the executive mastership are connected with a research of the evolution of the genres of instrumental music. I. INTRODUCTION The initial period of genesis and development of clarinet concert is investigated widely. Contemporary music in its various genres has become in many aspects a subject of scrupulous studies in musicology. It is known that the most early is the composition of Our research deals with professional problematics of the Antonio Paganelli indicated by the author as Concerto per instrumental concert genre, viewed more narrowly, namely, Clareto (1733). Possibly, it was written for chalumeau, the connected with clarinet performance. instrument-predecessor of the clarinet itself. But, before this time clarinet was used as one of the concertizing instruments The purpose of this article is to identify the situation in the genre of Concerto Grosso, particularly by J. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Peculiarities of Clarinet Concertos Form-Building in the Second Half of the 20th Century and the Beginning of the 21st Century Marina Chernaya and Yu Zhao* Abstract: The article deals with clarinet concertos composed in the 20th– 21st centuries. Many different works have been created, either in one or few parts; the longest concert that is mentioned has seven parts (by K. Meyer, 2000). Most of the concertos have 3 parts and the fast-slowly-fast kind of structure connected with the Italian overture; sometimes, the scheme has variants. Our question is: How does the concerto genre function during this period? To answer, we had to search many musical compositions. Sometimes the clarinet is accompanied by orchestra, other times it is surrounded by an ensemble of instruments. More than 100 concertos were found and analyzed. Examples of such concertos were written by C. Nielsen, P. Boulez, J. Adams, C. Debussy, M. Arnold, A. Copland, P. Hindemith, I. Stravinsky, S. Vassilenko, and the attention in the article is focused on them. A special complete analysis is made as regards “Domaines” for clarinet and 21 instruments divided in 6 groups, by Pierre Boulez that had a great role for the concert routine, based on the “aleatoric” principle. The conclusions underline the significant development of the clarinet concerto genre in the 20th -21st centuries, the high diversity of the compositions’ structures, the considerable expressiveness and technicality together with the soloist’s part in the expressive concertizing (as a rule). Further studies suggest the analysis of stylistic and structural peculiarities of the found compositions that are apparently to win their popularity with performers and listeners. -

Wie Aus Dem Moment Gestaltet Hansheinz Schneeberger Zum Achtzigsten Geburtstag

A-Schneeberger 6.10.2006 17:39 Uhr Seite 15 Schweizer Musikzeitung Nr. 10 / Oktober 2006 15 Wie aus dem Moment gestaltet Hansheinz Schneeberger zum achtzigsten Geburtstag Wenn ein Geiger regelmässig Solorezitale gibt, ist dies heute eher ungewöhnlich. Wenn dieser achtzig Jahre alt und noch auf der Höhe seines technischen Könnens ist, ja von Jahr zu Jahr wie ein edler Wein immer farbiger und tiefgründiger wird, dann kann es sich nur um das Phänomen Hansheinz Schneeberger handeln. Thomas Gartmann Als unlängst Thomas Zehetmair für das Violin- konzert Malchuth von Daniel Glaus absagte, zö- gerte er kaum, rechnete sich aus, dass er sechs bis sieben Tage für die Einstudierung brauche, grummelte etwas über zwei, drei vertrackte Grif- fe, suchte sich die Fingersätze und spielte eine wunderbar belebte Interpretation von höchster Prägnanz und Virtuosität ein. Auf der Geige begonnen hat der 1926 in Bern geborene Schneeberger mit sechs Jahren. Bis zum Diplomabschluss 1944 studierte er bei Wal- ter Kägi am heimischen Konservatorium, an- Hansheinz Schneeberger: «Es ist Aufgabe des Interpreten, die Fixierung in ein quasi improvisatorisches Werk schliessend bei Carl Flesch in Luzern und bei Bo- zurückzuführen.» ris Kamensky in Paris. 1958 bis 1961 war er Erster Konzertmeister im Sinfonieorchester des NDR Mal war es mit einer anderen Überra s c h u n g , Begeistert war er auch als Lehrer tätig, zuerst Hamburg; als Solist konzertierte er noch unter e i ner weiteren Verzögerung, einer neuen Fär- an den Konservatorien von Biel und Bern, ab Ernest Ansermet in Wien, Warschau, Stanford bung – und immer überzeugend, atemstockend. 1961 mit einer Meisterklasse an der Musikakade- und an der Weltausstellung in Montreal. -

Boosey & Hawkes

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Howell, Jocelyn (2016). Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16081/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire Jocelyn Howell PhD in Music City University London, Department of Music July 2016 Volume 1 of 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures...................................................................................................................................... -

The Canadian Clarinet Works Written for James Campbell

THE CANADIAN CLARINET WORKS WRITTEN FOR JAMES CAMPBELL by Laura Chalmers Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Eli Eban, Research Director and Chair __________________________________________ James Campbell __________________________________________ Kathleen McLean __________________________________________ Peter Miksza September 29, 2020 ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to the following people, without whom this document would not have been completed: To Prof. Campbell, Allan Gilliland, Phil Nimmons, Timothy Corlis, and Jodi Baker Contin, who gave their time and shared their recollections with me. To my wonderful friends, Emory Rosenow, Laura Kellogg, Mark Wallace, and Lilly Haley- Corbin, who not only read through this entire document to correct mistakes, but who also encouraged me and bolstered me as I wrote this paper. To my family, Mom, Marcus, and Leisha, who have always supported me and continue to do so through my Doctorate. Finally, to my husband, Jacob Darrow. This is as much his success as it is mine. iii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... -

The Publication History of Spohr's Clarinet Concertos

THE PUBLICATION HISTORY OF SPOHR'S CLARINET CONCERTOS by Keith Warsop N DISCUSSING the editions used for the recording by French clarinettist paul Meyer of Spohr's four concertos for the instrument on the Alpha label (released as a two-CD set, ALPHA 605, with the orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne), reviewers in the November 2012 issues of the Gramophone and,Internotional Record Review magazines came to some slightly misleading conclusions about this subject so that it has become important to clarify matters. Carl Rosman, writing in 1RR, ,authentic, said: "Meyer has also taken steps towards a more text fbr these concertos. While the clarinet works of Mozart, Brahms and Weber have seen various Urtext editions over the years, Spohr's concertos circulate only in piano reductions from the late nineteenth century ... Meyer has prepared his own editions from the best available sources (the manuscripts of all but No.4 have been lost but there are contemporary manuscript copies of the others held at the Louis Spohr Society in Kassel); this has certainly giu., him lreater freedom in the area of articulation, and also allowed him to adopt some more-flowing temios than the late nineteenth-century editions specify.', In the Gramophone, Nalen Anthoni stated: "Hermstedt demanded exclusive rights and, presumably, kept the autographs. Only that of No.4 was found, in 1960. The other works have been put together from manuscript copies. Paul Meyer seems largely attuned to the solo parts edited by stanley Drucker, the one-time principal ciarinettist of the New york philharmonic. Michael Collins [on the Hyperion label] is of similar mind, though both musicians add their own individual touches phrasing to and articulation. -

Program Notes

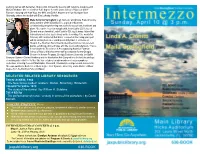

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Radio 3 Listings for 28 December 2019 – 3 January 2020 Page 1 of 16

Radio 3 Listings for 28 December 2019 – 3 January 2020 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 28 DECEMBER 2019 (conductor) BBC National Orchestra of Wales Jac van Steen (conductor) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000cpsr) 05:01 AM BIS BIS2408 (Hybrid SACD) - Released 3rd January 2020 Regensburger Domspatzen at Tage Alter Musik Judith Weir (1954-) String quartet Ravel: Jeux de Miroirs Leopold Mozart shows himself to be a serious composer at the Silesian Quartet Javier Perianes (piano) height of his powers with his Symphony in G and Missa Orchestre de Paris Solemnis. They are performed at the Tage Alter Musik festival 05:13 AM Josep Pons (conductor) in Regensburg, Germany, by the Regensburger Domspatzen and Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Harmonia Mundi HMM902326 the Hofkapelle Munich. Catriona Young presents. 4 Impromptus for piano, D 899 (No 4 in A flat) http://www.harmoniamundi.com/#!/albums/2571 Arthur Schnabel (piano) 01:01 AM 9.30am Building a Library Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) 05:21 AM Symphony in G 'Neue Lambacher', for strings Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721-1783) Laura Tunbridge discusses a wide range of approaches to Hofkapelle Munchen, Rudiger Lotter (conductor) Cantata, 'An den Flussen Babylons' Schumann's searing Heine cycle and recommends the key Johannes Happel (bass), Balthasar-Neumann-Chor, Balthasar- recording to keep for posterity. 01:18 AM Neumann-Ensemble, Detlef Bratschke (conductor) Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) 10.20am New Releases Missa Solemnis in C 05:33 AM Katja Stuber (soprano), Dorothee Rabsch (contralto), Robert Joaquín Turina (1882-1949) -

Shirley BRILL

Shirley BRILL Vzpon kariere Shirley Brill se je zael s solistinim nastopom z Izraelsko filharmonijo pod taktirko Zubina Mehte. Zatem je nastopila z mnogimi mednarodnimi orkestri, kot so Deutsches Symphonie Orchester, Hamburški simfoniki pod vodstvom Jeffreyja Tata, Simfonini orkester narodnega gledališa Praga, Komorni orkester iz Ženeve, Simfonini orkester poljskega radia in simfonini orkester iz Jeruzalema. Nedavno je kot solistka nastopila z Münchenskimi simfoniki v filharmoniji v Gasteigu. Shirley Brill je zmagovalka mednarodnega tekmovanja v Ženevi (2007), mednarodnega tekmovanja v Markneukirchnu (2006) in prejemnica posebne nagrade na mednarodnem tekmovanju ARD v Münchnu. Nastopila je na mednarodnih festivalih BBC Proms v Angliji, Radio France Festival v Montpellieru, Schubertiade v Avstriji, Davos Festival v Švici in na Mednarodnem festivalu komorne glasbe v Jeruzalemu. V Nemiji je nastopila na festivalih Schleswig-Holstein Festival, Rheingau Festival, Heidelberger Frühling in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival. Sodelovala je z umetniki, kot so Daniel Barenboim, Sabine Meyer, Emmanuel Pahud, Janine Jansen, Tabea Zimmermann, Jerusalem String Quartet, Fauré Piano Quartet in Trio di Clarone. S pianistom Jonathanom Anerjem redno sodelujeta kot Brillaner duo. Nastopila sta že v dvorani Carnegie v New Yorku, v Tonhalle v Zürichu, v Oriental Art Center v Šanghaju in v Beethovnovi hiši v Bonnu. Po konanem študiju v Izraelu pri prof. Yitzhaku Katzapu je Shirley Brill nadaljevala študij na Visoki šoli za glasbo v Lübecku pri prof. Sabine Meyer in na New England Conservatory v Bostonu pri prof. Richardu Stoltzmanu. Od leta 2012 Shirley Brill deluje kot profesorica na Akademiji za glasbo Hanns Eisler v Berlinu, leta 2016 pa je postala predavateljica na Akademiji Barenboim-Said. ********************************************************************************************************* Shirley Brill's career was launched with a performance as a soloist with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Zubin Mehta. -

Download the Clarinet Saxophone Classics Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2017 www.samekmusic.com Founded in 1992 by acclaimed clarinetist Victoria Soames Samek, Clarinet & Saxophone Classics celebrates the single reed in all its richness and diversity. It’s a unique specialist label devoted to releasing top quality recordings by the finest artists of today on modern and period instruments, as well as sympathetically restored historical recordings of great figures from the past supported by informative notes. Having created her own brand, Samek Music, Victoria is committed to excellence through recordings, publications, learning resources and live performances. Samek Music is dedicated to the clarinet and saxophone, giving a focus for the wonderful world of the single reed. www.samek music.com For further details contact Victoria Soames Samek, Managing Director and Artistic Director Tel: + 44 (0) 20 8472 2057 • Mobile + 44 (0) 7730 987103 • [email protected] • www.samekmusic.com Central Clarinet Repertoire 1 CC0001 COPLAND: SONATA FOR CLARINET Clarinet Music by Les Six PREMIERE RECORDING Featuring the World Premiere recording of Copland’s own reworking of his Violin Sonata, this exciting disc also has the complete music for clarinet and piano of the French group known as ‘Les Six’. Aaron Copland Sonata (premiere recording); Francis Poulenc Sonata; Germaine Tailleferre Arabesque, Sonata; Arthur Honegger Sonatine; Darius Milhaud Duo Concertant, Sonatine Victoria Soames Samek clarinet, Julius Drake piano ‘Most sheerly seductive record of the year.’ THE SUNDAY TIMES CC0011 SOLOS DE CONCOURS Brought together for the first time on CD – a fascinating collection of pieces written for the final year students studying at the paris conservatoire for the Premier Prix, by some of the most prominent French composers. -

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8.