On Naming, Race-Marking, and Race-Making in Cuba In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN TAX LEADERS WOMEN in TAX LEADERS | 4 AMERICAS Latin America

WOMEN IN TAX LEADERS THECOMPREHENSIVEGUIDE TO THE WORLD’S LEADING FEMALE TAX ADVISERS SIXTH EDITION IN ASSOCIATION WITH PUBLISHED BY WWW.INTERNATIONALTAXREVIEW.COM Contents 2 Introduction and methodology 8 Bouverie Street, London EC4Y 8AX, UK AMERICAS Tel: +44 20 7779 8308 4 Latin America: 30 Costa Rica Fax: +44 20 7779 8500 regional interview 30 Curaçao 8 United States: 30 Guatemala Editor, World Tax and World TP regional interview 30 Honduras Jonathan Moore 19 Argentina 31 Mexico Researchers 20 Brazil 31 Panama Lovy Mazodila 24 Canada 31 Peru Annabelle Thorpe 29 Chile 32 United States Jason Howard 30 Colombia 41 Venezuela Production editor ASIA-PACIFIC João Fernandes 43 Asia-Pacific: regional 58 Malaysia interview 59 New Zealand Business development team 52 Australia 60 Philippines Margaret Varela-Christie 53 Cambodia 61 Singapore Raquel Ipo 54 China 61 South Korea Managing director, LMG Research 55 Hong Kong SAR 62 Taiwan Tom St. Denis 56 India 62 Thailand 58 Indonesia 62 Vietnam © Euromoney Trading Limited, 2020. The copyright of all 58 Japan editorial matter appearing in this Review is reserved by the publisher. EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA 64 Africa: regional 101 Lithuania No matter contained herein may be reproduced, duplicated interview 101 Luxembourg or copied by any means without the prior consent of the 68 Central Europe: 102 Malta: Q&A holder of the copyright, requests for which should be regional interview 105 Malta addressed to the publisher. Although Euromoney Trading 72 Northern & 107 Netherlands Limited has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of this Southern Europe: 110 Norway publication, neither it nor any contributor can accept any regional interview 111 Poland legal responsibility whatsoever for consequences that may 86 Austria 112 Portugal arise from errors or omissions, or any opinions or advice 87 Belgium 115 Qatar given. -

Biography of a Runaway Slave</Cite>

Miguel Barnet. Biography of a Runaway Slave. Willimantic, Conn.: Curbstone Press, 1994. 217 pp. $11.95, paper, ISBN 978-1-880684-18-4. Reviewed by Dale T. Graden Published on H-Ethnic (October, 1996) Few documentary sources exist from the Car‐ preter as "the frst personal and detailed account ibbean islands and the Latin American mainland of a Maroon [escaped] slave in Cuban and Spanish written by Africans or their descendants that de‐ American literature and a valuable document to scribe their life under enslavement. In Brazil, two historians and students of slavery" (Luis, p. 200). mulatto abolitionists wrote sketchy descriptions This essay will explore how testimonial literature of their personal experiences, and one autobiog‐ can help us better to understand past events. It raphy of a black man was published before eman‐ will also examine problems inherent in interpret‐ cipation. In contrast, several thousand slave nar‐ ing personal testimony based on memories of ratives and eight full-length autobiographies were events that occurred several decades in the past. published in the United States before the outbreak Esteban Mesa Montejo discussed his past with of the Civil War (1860-1865) (Conrad, p. xix). In the Cuban ethnologist Miguel Barnet in taped in‐ Cuba, one slave narrative appeared in the nine‐ terviews carried out in 1963. At the age of 103, teenth century. Penned by Juan Francisco Man‐ most likely Esteban Montejo understood that he zano, the Autobiografia (written in 1835, pub‐ was the sole living runaway slave on the island lished in England in 1840, and in Cuba in 1937) re‐ and that his words and memories might be con‐ counted the life of an enslaved black who learned sidered important enough to be published. -

Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound International Immersion Program Papers Student Papers 2015 A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ international_immersion_program_papers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald Jones, "A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba," Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 9 (2015). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Immersion Program Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaA Revolution Deferred sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfRacism in Cuba 4/25/2015 ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj Ron Jones klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Slavery in Cuba ....................................................................................................................................... -

Freedom's Mirror Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution by Ada Ferrer

Freedom’s Mirror During the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804,arguablythemostradi- cal revolution of the modern world, slaves and former slaves succeeded in ending slavery and establishing an independent state. Yet on the Spanish island of Cuba, barely fifty miles away, the events in Haiti helped usher in the antithesis of revolutionary emancipation. When Cuban planters and authorities saw the devastation of the neighboring colony, they rushed to fill the void left in the world market for sugar, to buttress the institutions of slavery and colonial rule, and to prevent “another Haiti” from happening in their territory. Freedom’s Mirror follows the reverberations of the Haitian Revolution in Cuba, where the violent entrenchment of slavery occurred at the very moment that the Haitian Revolution provided a powerful and proximate example of slaves destroying slavery. By creatively linking two stories – the story of the Haitian Revolution and that of the rise of Cuban slave society – that are usually told separately, Ada Ferrer sheds fresh light on both of these crucial moments in Caribbean and Atlantic history. Ada Ferrer is Professor of History and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University. She is the author of Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898,whichwonthe2000 Berk- shire Book Prize for the best first book written by a woman in any field of history. Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 131.111.164.128 on Tue May 03 17:50:21 BST 2016. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139333672 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2016 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 131.111.164.128 on Tue May 03 17:50:21 BST 2016. -

Martinez V. Columbian Emeralds

For Publication IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS FRANKLIN MARTINEZ, ) S. Ct. Civ. No. 2007-06 ) S. Ct. Civ. No. 2007-11 Appellant/Plaintiff, ) Re: Super. Ct. Civ. No. 641-2000 ) v. ) ) COLOMBIAN EMERALDS, INC., ) ) Appellee/Defendant. ) ) On Appeal from the Superior Court of the Virgin Islands Argued: July 19, 2007 Filed: March 4, 2009 BEFORE: RHYS S. HODGE, Chief Justice; MARIA M. CABRET, Associate Justice; and IVE ARLINGTON SWAN, Associate Justice. APPEARANCES: Joseph B. Arellano, Esq. Arellano & Associates St. Thomas, U.S.V.I. Attorney for Appellant A. Jeffrey Weiss, Esq. A.J. Weiss & Associates St. Thomas, U.S.V.I. Attorney for Appellee OPINION OF THE COURT HODGE, Chief Justice. Appellant Franklin Martinez (“Martinez”) challenges the Superior Court’s order dismissing his complaint and ordering him to arbitration, and denying both his subsequent motion for reconsideration of the dismissal and his companion motion for stay of the proceedings pending arbitration. Martinez also challenges the award of attorney’s fees to Appellee Colombian Emeralds, Inc. (“CEI”). For the reasons stated below, the dismissal of the complaint and award of attorneys’ Martinez v. Colombian Emeralds, Inc. S. Ct. Civ. Nos. 2007-006 & 2007-011 Opinion of the Court Page 2 of 15 fees will be reversed. I. BACKGROUND Martinez, a citizen of Colombia and Switzerland, filed suit against CEI, a Virgin Islands corporation, alleging that he possessed an interest in certain real property located in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, titled in CEI’s name. He sought an injunction to prevent CEI from selling the property or listing it for sale. -

The Maritime Voyage of Jorge Juan to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1735-1746)

The Maritime Voyage of Jorge Juan to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1735-1746) Enrique Martínez-García — Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas* María Teresa Martínez-García — Kansas University** Translated into English (August 2012) One of the most famous scientific expeditions of the Enlightenment was carried out by a colorful group of French and Spanish scientists—including the new Spanish Navy lieutenants D. Jorge Juan y Santacilia (Novelda 1713-Madrid 1773) and D. Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Giralt (Seville 1716-Isla de León 1795)—at the Royal Audience of Quito in the Viceroyalty of Peru between 1736 and 1744. There, the expedition conducted geodesic and astronomical observations to calculate a meridian arc associated with a degree in the Equator and to determine the shape of the Earth. The Royal Academy of Sciences of Paris, immersed in the debate between Cartesians (according to whom the earth was a spheroid elongated along the axis of rotation (as a "melon")) and Newtonians (for whom it was a spheroid flattened at the poles (as a "watermelon")), decided to resolve this dispute by comparing an arc measured near the Equator (in the Viceroyalty of Peru, present-day Ecuador) with another measured near the North Pole (in Lapland). The expedition to the Equator, which is the one that concerns us in this note, was led by Louis Godin (1704-1760), while Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698-1759) headed the expedition to Lapland. The knowledge of the shape and size of the Earth had great importance for the improvement of cartographic, geographic, and navigation techniques during that time. -

Copyright by Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez 2010

Copyright by Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839-1886 Committee: Jonathan C. Brown, Supervisor Evelyn Hu-DeHart Seth W. Garfield Frank A. Guridy Susan Deans-Smith Madeline Y. Hsu Chinese Coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, Labor, and Immigration, 1839-1886 by Benjamin Nicolas Narvaez, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2010 Dedication To my parents Leon and Nancy, my brother David, and my sister Cristina. Acknowledgements Throughout the process of doing the research and then writing this dissertation, I benefitted immensely from the support of various individuals and institutions. I could not have completed the project without their help. I am grateful to my dissertation committee. My advisor, Dr. Jonathan Brown, reasonable but at the same time demanding in his expectations, provided me with excellent guidance. In fact, during my entire time as a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, he was a model of the excellence of which a professional historian is capable. Dr. Evelyn Hu-DeHart was kind enough to take an interest in my work and gave me valuable advice. This project would not have been possible without her pioneering research on Asians in Latin America. I also wish to thank the other members of my dissertation committee – Dr. -

Afro-Asian Sociocultural Interactions in Cultural Production by Or About Asian Latin Americans

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 26 September 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201809.0506.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Humanities 2018, 7, 110; doi:10.3390/h7040110 Afro-Asian Sociocultural Interactions in Cultural Production by or About Asian Latin Americans Ignacio López-Calvo University of California, Merced [email protected] Abstract This essay studies Afro-Asian sociocultural interactions in cultural production by or about Asian Latin Americans, with an emphasis on Cuba and Brazil. Among the recurrent characters are the black slave, the china mulata, or the black ally who expresses sympathy or even marries the Asian character. This reflects a common history of bondage shared by black slaves, Chinese coolies, and Japanese indentured workers, as well as a common history of marronage.1 These conflicts and alliances between Asians and blacks contest the official discourse of mestizaje (Spanish-indigenous dichotomies in Mexico and Andean countries, for example, or black and white binaries in Brazil and the Caribbean), which, under the guise of incorporating the Other, favored whiteness, all the while attempting to silence, ignore, or ultimately erase their worldviews and cultures. Keywords: Afro-Asian interactions, Asian Latin American literature and characters, Sanfancón, china mulata, “magical negro,” chinos mambises, Brazil, Cuba, transculturation, discourse of mestizaje Among the recurrent characters in literature by or about Asians in Latin America are the black slave, the china mulata, or the -

CASTLEMAN, BRUCE A. Building the King's Highway. Labor, Society, and Family on Mexico's Caminos Reales 1757–

Book Reviews 149 Castleman, Bruce A. Building the King’s Highway. Labor, Society, and Family on Mexico’s Caminos Reales 1757–1804. University of Arizona Press, Tucson 2005. xii, 163 pp. $39.95; DOI: 10.1017/S0020859007032865 Despite its distinction as the wealthiest and most populated colony of the Spanish empire, Mexico remained poorly developed, suffering from inadequate infrastructure even as late as the end of the colonial period. For decades Mexico’s mercantile elite complained about the poverty of the colony’s system of transportation, especially the lack of an easily navigable road between Mexico City and the principle port of Veracruz. While construction occurred in fits and starts, colonial officials truly embraced the goal of constructing an improved road only in the final decade of the eighteenth century. By the end of Spanish rule, the road was still incomplete. In this interesting study, Bruce Castleman examines the social and economic history of the construction of the Camino Real, the ‘‘King’s Highway’’. The work is largely based on two types of rich archival materials which Castleman skillfully employs. In the first several chapters Castleman analyzes highly suggestive employment records which provide a window into the region’s labor history. A later chapter profits from Castleman’s statistical comparison of censuses taken for the city of Orizaba in the years 1777 and 1793. Along the way, the author makes many interesting arguments. Following an introduction, Chapter 2 presents an overview of the politics surrounding the road’s construction. Building of the highway between Mexico City and Veracruz actually entailed numerous individual localized projects which the viceregal government hoped would eventually connect to one another. -

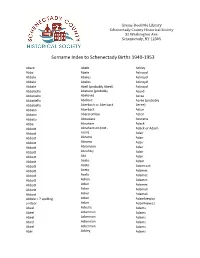

Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Abare Abele Ackley Abba Abele Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abell (probably Abeel) Ackroyd Abbatiello Abelone (probably Acord Abbatiello Abelove) Acree Abbatiello Abelove Acree (probably Abbatiello Aberbach or Aberback Aeree) Abbato Aberback Acton Abbato Abercrombie Acton Abbato Aboudara Acucena Abbe Abraham Adack Abbott Abrahamson (not - Adack or Adach Abbott nson) Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abramson Adair Abbott Abrofsky Adair Abbott Abt Adair Abbott Aceto Adam Abbott Aceto Adamczak Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Acken Adamec Abbott Acker Adamec Abbott Acker Adamek Abbott Acker Adamek Abbzle = ? spelling Acker Adamkiewicz unclear Acker Adamkiewicz Abeel Ackerle Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abel Ackley Adams Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Adams Adamson Ahl Adams Adanti Ahles Adams Addis Ahman Adams Ademec or Adamec Ahnert Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adriance Ahrens Adams Adsit Aiken Adams Aeree Aiken Adams Aernecke Ailes = ? Adams Agans Ainsworth Adams Agans Aker (or Aeher = ?) Adams Aganz (Agans ?) Akers Adams Agare or Abare = ? Akerson Adams Agat Akin Adams Agat Akins Adams Agen Akins Adams Aggen Akland Adams Aggen Albanese Adams Aggen Alberding Adams Aggen Albert Adams Agnew Albert Adams Agnew Albert or Alberti Adams Agnew Alberti Adams Agostara Alberti Adams Agostara (not Agostra) Alberts Adamski Agree Albig Adamski Ahave ? = totally Albig Adamson unclear Albohm Adamson Ahern Albohm Adamson Ahl Albohm (not Albolm) Adamson Ahl Albrezzi Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. -

Characterization of Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue

J. Perinat. Med. 2016; 44(7): 813–835 Shali Mazaki-Tovi*, Adi L. Tarca, Edi Vaisbuch, Juan Pedro Kusanovic, Nandor Gabor Than, Tinnakorn Chaiworapongsa, Zhong Dong, Sonia S. Hassan and Roberto Romero* Characterization of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue transcriptome in pregnant women with and without spontaneous labor at term: implication of alternative splicing in the metabolic adaptations of adipose tissue to parturition DOI 10.1515/jpm-2015-0259 groups (unpaired analyses) and adipose tissue regions Received July 27, 2015. Accepted October 26, 2015. Previously (paired analyses). Selected genes were tested by quantita- published online March 19, 2016. tive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Abstract Results: Four hundred and eighty-two genes were differ- entially expressed between visceral and subcutaneous Objective: The aim of this study was to determine gene fat of pregnant women with spontaneous labor at term expression and splicing changes associated with par- (q-value < 0.1; fold change > 1.5). Biological processes turition and regions (visceral vs. subcutaneous) of the enriched in this comparison included tissue and vascu- adipose tissue of pregnant women. lature development as well as inflammatory and meta- Study design: The transcriptome of visceral and abdomi- bolic pathways. Differential splicing was found for 42 nal subcutaneous adipose tissue from pregnant women at genes [q-value < 0.1; differences in Finding Isoforms using term with (n = 15) and without (n = 25) spontaneous labor Robust Multichip Analysis scores > 2] between adipose was profiled with the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Exon tissue regions of women not in labor. Differential exon 1.0 ST array. Overall gene expression changes and the dif- usage associated with parturition was found for three ferential exon usage rate were compared between patient genes (LIMS1, HSPA5, and GSTK1) in subcutaneous tissues. -

Start Number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy

Start number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy Frølund Jensen Kongens lyngby, Denmark 89:20:46 11002 Emil Boström Lag Nord Linköping, Sweden 98:19:04 11003 Lovisa Johansson Lag Nord Burträsk, Sweden 98:19:02 11005 Maurice Lagershausen Huddinge, Sweden 102:01:54 11011 Hyun jun Lee Korea, (south) republic of 122:40:49 11012 Viggo Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:24 11013 Richard Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:28 11014 Rasmus Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11015 Rafael Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11017 Marie Zølner Hillerød, Denmark 82:11:49 11018 Niklas Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11019 Viggo Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11020 Damian Sulik #StopComplaining Siegen, Germany 101:13:24 11023 Bruno Svendsen Tylstrup, Denmark 74:48:08 11024 Philip Oswald Lakeland, USA 55:52:02 11025 Virginia Marshall Lakefield, Canada 55:57:54 11026 Andreas Mathiasson Backyard Heroes Ödsmål, Sweden 75:12:02 11028 Stine Andersen Brædstrup, Denmark 104:35:37 11030 Patte Johansson Tiger Södertälje, Sweden 80:24:51 11031 Frederic Wiesenbach BB Dahn, Germany 101:21:50 11032 Romea Brugger BB Berlin, Germany 101:22:44 11034 Oliver Freudenberg Heyda, Germany 75:07:48 11035 Jan Hennig Farum, Denmark 82:11:50 11036 Robert Falkenberg Farum, Denmark 82:11:51 11037 Edo Boorsma Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:34 11038 Trijneke Stuit Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:35 11040 Sebastian Keck TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:01 11041 Tatjana Kage TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:02 11042 Eun Lee