Strategies-Higher-Education-Sri.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthropogenic Impacts on Urban Coastal Lagoons in the Western and North-Western Coastal Zones of Sri Lanka

1 2 Anthropogenic Impacts on Urban Coastal Lagoons in the Western and North-western Coastal Zones of Sri Lanka Jinadasa Katupotha Department of Geography, University of Sri Jayewardenepura Gangodawila, Nugegoda 10250, Sri Lanka [email protected] Abstract Six lagoons from Negombo to Puttalam, along the Western and North Western coast of Sri Lanka, show signs of some change due to urbanization-related anthropological activities. Identified activities have direct implications on morphological features of lagoons, elimination of wetlands (mangrove swamps and marshy lands) and pasture lands, land degradation due to encroachment for shrimp farms, shrinking of lagoons, and production of higher nutrient and heavy metal loads, decline in bird and fish populations and degradation of the scenic beauty. As a result, the lagoon ecosystems have suffered to such a degree that numerous faunal and floral species have disappeared or have diminished considerably over the last few years. All these anthropogenic impacts were identified by the author during 1992, 2002, and 2006 as well as in a study on “Lagoons in Sri Lanka” conducted by IWMI between 2011 and 2012. Key words: Anthropogenic Impacts, Urban Coastal Lagoons, Garbage accumulation, Awareness program Introduction The island of Sri Lanka has 82 coastal lagoons that support a variety of plants and animals, and the economy [1]. Anthropogenic impacts, particularly lagoon fishing, human occupation of the land and water contamination have considerably reduced the faunal and floral population to a point that some of them are in danger of extinction. Such danger of extinction has been accelerated in urban lagoons of the western and northwestern coastal zones, e.g. -

Hand Book Cover Page 2016

About this HandBook This handbook provides general information about The Open University of Sri Lanka and in particular about the Faculty of Natural Sciences. You can also use it as a guide for the undergraduate Programmes/ Courses offered by the Faculty of Natural Sciences. From this handbook, you will find out about: the study system adopted by The Open University the undergraduate study Programmes/Courses offered by the Faculty how you can register for Courses/Programmes the support you will receive to follow Courses/Programmes administrative divisions you may have to frequently contact the teaching and administrative staff of the Faculty how you can obtain exemptions based on prior qualifications course fees applicable for your Courses/Programmes scholarships/ bursaries and other awards available awards criteria for degrees offered by the Faculty your responsibilities as a student of The Open University Your responsibilities as a student of The OUSL The Open University of Sri Lanka is committed to a working and learning environment which is friendly, peaceful and safe for all staff and students. Such an environment can only be created by a collective effort of all concerned parties. Students being the largest category in the University, their conduct and behaviour have a considerable impact on the environment of the University. The Faculty of Natural sciences wishes to emphasise the following regarding responsibilities of students. Always carry the Record Book with you while in the University, as a proof of identity. Comply with the rules and regulations of the University. The General By Law for student discipline, No 02 of 2008, OUSL and Prohibition of Ragging and Other Forms of Violence in Educational Institutions Act, No.20 of 1998 (Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka) require the University to prevent or effectively deal with any disturbances to the working and learning environment. -

Student Handbook 2017/2018

STUDENT HANDBOOK 2017/2018 Faculty of Business University of Moratuwa Page 0 Contents Message from the Vice-Chancellor Message from the Dean Message from the Registrar Welcome to University of Moratuwa Vision and Mission of University of Moratuwa Introduction to Academic Entities Message from Head/Department of Decision Sciences Message from Head/Department of Industrial Management Message from Head/Department of Management of Technology Academic and Non-Academic Staff of Faculty of Business Other Academic Entities Undergraduate Studies Division Department of Languages Career Guidance Unit Library Student Welfare Services Student Counseling Student Accommodation Canteen Facilities Clubs and Societies University Health Centre Industrial Training, Industry Collaboration and Special Events Laboratory Facilities and Resources at Faculty of Business Career Prospects of Business Science Graduates Undergraduate Degree Programme Semester Coordinators and Programme Coordinators Teaching and Learning Strategy Curriculum: Common Core (Semesters 1, 2 & 3) Performance Criteria Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Academic Calendar Page 1 Message from the Vice-Chancellor It is with great pleasure that I warmly welcome you to the University of Moratuwa as the inaugural batch to our newly established Faculty of Business to pursue education leading to a brand new degree BSc in Business Science. University of Moratuwa has gained reputation as the best technological University in Sri Lanka. It is the most sought after University by the students for education in many disciplines and by the employers for recruitment. The University’s overall employment ratio of all the courses at the time of the convocation is around 95%, the highest in any university in Sri Lanka and comparable to any world’s best university. -

Student Handbook

SSTTUUDDEENNTT HHAANNDDBBOOOOKK Academic year 2015/2016 Faculty of Engineering University of Ruhuna Galle Sri Lanka HANDBOOK Academic Year 2015/2016 Faculty of Engineering University of Ruhuna Galle Sri Lanka HANDBOOK Academic Yeari 2014/2015 This handbook is provided for information purposes only, and its contents are subjected to change without notice. The information herein is made available with the understanding that the University will not be held responsible for its completeness or accuracy. The University will accept no liability whatsoever for any damage or losses, direct or indirect, arising from or related to use of this handbook. In addition to the handbook, you are highly advised to refer the updated circulars for clarifications. Published by: Faculty of Engineering University of Ruhuna Hapugala, Wakwella Galle 80000 Sri Lanka http://www.eng.ruh.ac.lk ii Our Vision To be the centre of excellence in engineering education and research of the nation Our Mission To create opportunities for the benefit of the society in engineering and applied technologies through education, research and associated services iii Table of Contents 1 THE OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RUHUNA AND THE STAFF OF THE FACULTY OF ENGINEERING ......... 1 1.1 THE OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RUHUNA ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 STAFF OF THE FACULTY OF ENGINEERING ............................................................................................................. 2 M.Sc.(Gdansk), -

IUC NN Commission Members from Sri Lanka

International Union for Conservation of Nature IIUUCCNN Commission Members from Sri Lanka Volume I – (Updated on 15.06.2015) IUCN Commission Members from Sri Lanka Message from IUCN National Committee Chair One of the IUCN strengths is to bring ecosystem related information, science and advise into the sustainable development processes. In that context IUCN Sri Lanka has contributed in the past towards a number of national policy and on the ground efforts. At a time post- conflict development in Sri Lanka is advancing fast with potential increase of the pressure on the natural resources. Management of the natural capital in a sustainable way while supporting development is a major challenge where information based multi-sector approaches are very much needed. Already the IUCN developed information on biodiversity, marine and coastal and water resources etc. are being used by the Government, Non-Government and Private Sector, extensively. However Sri Lanka has not fully utilized the potential contribution of IUCN Commissions and its membership. As the new Chairperson of the IUCN National Council, I wish to take this opportunity to express my appreciation for the contributions by the IUCN Commissions and Commission members in ensuring this planet a better place for us and the generations to come. Looking forward to work with you more and hope this compendium of experts will be helpful for all and expand to include other Sri Lankan experts as well. Anura Sathurusinghe, Conservator General of Forests and Chairperson, IUCN National Committee 2 IUCN Commission Members from Sri Lanka Forward This directory is prepared for the first time to capture the information on IUCN Sri Lanka related entities. -

Thousand Years of Hydraulic Civilization Some Sociotechnical Aspects of Water Management

Thousand Years of Hydraulic Civilization Some Sociotechnical Aspects of Water Management H.A.H. Jayanesa1 and John S. Selker2 1. Department of Geology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. [email protected]; [email protected]; 94-81-2389156 (℡); 94-81-2224174(¬) 2. Department of Bioengineering, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA. [email protected]; 541-737-6304 (℡); 541-737-2082(¬) Abstract Sri Lanka had efficient hydraulic civilization for a period of thousand years from 200 BC till 1200 AD. Out of its 103 drainage basins, those underneath in the dry zone were successfully irrigated through system of tanks and diversion canals. Sociotechnical aspects of water management seem efficient and well performed in the construction and maintenance of these tank and canal systems. It is believed that the king and the regional chieftains perform very strong tight management. In addition strategic use of both top-down and bottom-up initiatives as well as private partnerships with their own tanks and maintenance systems were supported for the efficient maintenance and management. Though there are a number of contradictory points affecting the different ethnic and religious groups, the Dublin principles have been used at various decision-making stages by the present governments. However, the current political, economic and technical performances are not geared enough for such efficient water management. The religious, ethical and moral aspects interwove with the ancient civilization, were the basis for maintenance and management of the hydraulic systems and subsequent upheaval in the society. Therefore, we argued that for successful water resources development programs need community engagement, sound technology and timely resources. -

Library Review Report, University of Moratuwa I

Library Review Report, University of Moratuwa I CONTENTS Page 1. External Review Process 1 2. Background of the University and the Library 2 3. Findings of the Review Team 3 3.1. Vision, Mission and Objectives 3 3.2. Management 3 3.3. Resources 4 3.4. Services 5 3.5. Integration 6 3.6. Contribution to Academic Staff 7 3.7. Networking 8 3.8. Evaluation 8 4. Recommendations 9 5. Annexes 10 Library Review Report, University of Moratuwa II 1. EXTERNAL REVIEW PROCESS The external review process of libraries is planned to upgrade the university library service and to share good practices without imposing an additional burden on the libraries under review. The aim is to use evidence and data generated and used by the library itself to appraise quality of its services. Greater the reliance of external quality assessment upon the library’s own evidence of self evaluation, greater the prospect that stands will be safeguarded and quality will be enhanced. Purposes of the external review process in libraries are to: (1) safeguard the quality and effectiveness of library services in Sri Lankan universities; (2) facilitate continuous quality improvement; (3) encourage good management of university libraries; (4) instill confidence in a library’s capacity to safeguard the quality and effectiveness of its services, both internally and externally; (5) identify and share good practices in the provision library services; (6) achieve accountability through external quality assessment and a public report; and (7) provide systematic, clear and assessable information on the university library services. Main features of the external review process includes: (1) production of an analytical Self Evaluation Report (SER) by the library staff; (2) review against the vision, mission, goals and objectives contained in the SER and a review visit of 3 days; and (3) publishing the review report with judgments, and the strengths/good practices and weaknesses identified. -

A Study Based on Sri Lankan University System

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Gyandhara International Academic Publication (GIAP): Journals International Journal of Management, Innovation & Entrepreneurial Research eISSN: 2395-7662, Vol. 5, No 1, 2019, pp 40-48 https://doi.org/10.18510/ijmier.2019.516 IMPACT OF INSTITUTION FACTORS TO UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE: A STUDY BASED ON SRI LANKAN UNIVERSITY SYSTEM IMS Weerasinghe1*, HH Dedunu2 1Department of Business Management, Faculty of Management Studies, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka, 2Department of Accountancy and Finance, Faculty of Management Studies, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka. Email: 1*[email protected], [email protected] Article History: Received on 25th October, Revised on 25th November, Published on 24th December 2019 Abstract Purpose: The study explored the impact of institutional factors have on the university-industry knowledge exchange based on the Sri Lankan university system. Methodology: The study is quantitative and explanatory by nature and it applied the deductive method and questionnaire survey strategy. The study conducted with minimum interference of researcher and individual academics is the unit of analysis. The types of knowledge interaction, university-industry knowledge exchange, and institutional factors were the independent, dependent and moderating variables respectively. A Structural Equation Model is deployed on collected data to explore the moderating impact of the institutional factor on the university-industry knowledge exchange. Implications: It implies that the level of joint, contract research activities, human resource mobility, and training of academic staff are largely wider on the conducive environment and sophisticated facilities of the university. -

National Wetland DIRECTORY of Sri Lanka

National Wetland DIRECTORY of Sri Lanka Central Environmental Authority National Wetland Directory of Sri Lanka This publication has been jointly prepared by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) in Sri Lanka and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The preparation and printing of this document was carried out with the financial assistance of the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Sri Lanka. i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CEA, IUCN or IWMI concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the CEA, IUCN or IWMI. This publication has been jointly prepared by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Sri Lanka and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The preparation and publication of this directory was undertaken with financial assistance from the Royal Netherlands Government. Published by: The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, Sri Lanka. Copyright: © 2006, The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the International Water Management Institute. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. -

History Education and Peace Promotion in Sri Lanka the Interplay Between Teacher Agency and the Formal Curriculum

History education and peace promotion in Sri Lanka The interplay between teacher agency and the formal curriculum (Point Pedro, photo by Rowan Cullen, 11 – 3 – 2019) Master thesis Anouk L. Strandstra International Development Studies Graduate School of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES HISTORY EDUCATION AND PEACE PROMOTION IN SRI LANKA: THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN TEACHER AGENCY AND THE FORMAL CURRICULUM A master thesis in International Development Studies Written by Anouk L. Strandstra Under the supervision of Dr. Mieke Lopes Cardozo Master International Development Studies Student number: 10587543 Second reader: Christel Eijkholt Word count: 26735 (incl. in-text references) Date: 15 – 06 – 2019 2 Abstract The bomb attacks during the Easter celebrations on the 21st of march 2019, once again illustrated the tension between societal groups in Sri Lanka’s complex post-war society. In this context, history education can be crucial in supporting or undermining peace within the society. This research assesses the relation between history education and peace promotion, hereby looking at the interplay between the formal curriculum and teacher agency, the latter is defined as the space of an actor to manoeuvre in relation to a structure. As such, the main research question is: How does the interplay between the formal curriculum and secondary history teachers’ agency support or undermine the peace promoting capacities of history education? Looking at this interplay allows for a comprehensive understanding of the relation between history education and peace promotion, which is unique in this field as the majority of research done thus far either focus on the formal curriculum or on teacher agency. -

World Bank Document

Promoting University-Industry in Sri LankaPromoting Collaboration Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Larsen, Bandara, Esham, and Unantenne Larsen, Bandara, Promoting University-Industry Public Disclosure Authorized Collaboration in Sri Lanka Status, Case Studies, and Policy Options Kurt Larsen, Deepthi C. Bandara, Mohamed Esham, and Ranmini Unantenne Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting University-Industry Collaboration in Sri Lanka DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Promoting University-Industry Collaboration in Sri Lanka Status, Case Studies, and Policy Options Kurt Larsen, Deepthi C. Bandara, Mohamed Esham, and Ranmini Unantenne © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

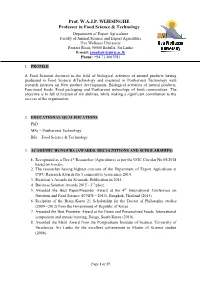

Prof. W.A.J.P. WIJESINGHE Professor in Food Science & Technology

Prof. W.A.J.P. WIJESINGHE Professor in Fo od Science & Technology Department of Export Agriculture Faculty of Animal Science and Export Agriculture Uva Wellassa University Passara Road, 90000 Badulla, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +94 71 4667981 1. PROFILE A Food Scientist doctored in the field of biological activities of natural products having graduated in Food Science &Technology and mastered in Postharvest Technology with research interests on New product developments, Biological activities of natural products, Functional foods, Food packaging and Postharvest technology of fresh commodities. The objective is to full utilization of my abilities, while making a significant contribution to the success of the organization. 2. EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS PhD MSc – Postharvest Technology BSc – Food Science & Technology 3. ACADEMIC HONOURS (AWARDS, RECOGNITIONS AND SCHOLARSHIPS) 1. Recognized as a Tire 4* Researcher (Agriculture) as per the UGC Circular No.05/2018 based on h-index. 2. The researcher having highest citations of the Department of Export Agriculture at UWU Research Awards for 5 consecutive years since 2014. 3. President’s Awards for Scientific Publication in 2014. 4. Business Solution Awards 2015 - 3rd place. 5. Awarded the Best Paper/Presenter Award at the 4th International Conference on Nutrition and Food Science (ICNFS – 2015), Bangkok, Thailand (2015). 6. Recipient of the Brain Korea 21 Scholarship for the Doctor of Philosophy studies (2009 –2012) from the Government of Republic of Korea. 7. Awarded the Best Presenter Award at the Green and Personalized Foods, International symposium and annual meeting, Daegu, South Korea (2010). 8. Awarded the Merit Award from the Postgraduate Institute of Science, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka for the excellent achievement in Master of Science studies (2008).