Problem-Solving in Canadals Courtrooms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Education of a Judge Begins Long Before Judicial Appointment

T H E EDUCATION O F A JUD G E … The Honourable Brian Lennox, Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice The education of a judge begins long before judicial appointment. Judges are first and foremost lawyers. In Canada, that means that they typically have an undergraduate university degree1, followed by a three‐year degree from a Faculty of Law, involving studies in a wide variety of legal subjects, including contracts, real estate, business, torts, tax law, family, civil and criminal law, together with practice‐ oriented courses on the application of the law. The law degree is followed by a period of six to twelve months of practical training with a law firm. Before being allowed to work as a lawyer, the law school graduate will have to pass a set of comprehensive Law Society exams on the law, legal practice and ethics. In total, most lawyers will have somewhere between seven and nine years of post‐high school education when they begin to practice. It is not enough to have a law degree in order to be appointed as a judge. Most provinces and the federal government2 require that a lawyer have a minimum of 10 years of experience before being eligible for appointment. It is extremely rare that a lawyer is appointed as a judge with only 10 years’ experience. On average, judges have worked for 15 to 20 years as a lawyer before appointment and most judges are 45 to 52 years of age at the time of their appointment. They come from a variety of backgrounds and experiences and have usually practised before the courts to which they are appointed. -

Superior Court of Québec 2010 2014 Activity Report

SUPERIOR COURT OF QUÉBEC 2010 2014 ACTIVITY REPORT A COURT FOR CITIZENS SUPERIOR COURT OF QUÉBEC 2010 2014 ACTIVITY REPORT A COURT FOR CITIZENS CLICK HERE — TABLE OF CONTENTS The drawing on the cover is the red rosette found on the back of the collar of the judge’s gown. It was originally used in England, where judges wore wigs: their black rosettes, which were applied vertically, prevented their wigs from rubbing against and wearing out the collars of their gowns. Photo on page 18 Robert Levesque Photos on pages 29 and 30 Guy Lacoursière This publication was written and produced by the Office of the Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Québec 1, rue Notre-Dame Est Montréal (Québec) H2Y 1B6 Phone: 514 393-2144 An electronic version of this publication is available on the Court website (www.tribunaux.qc.ca) © Superior Court of Québec, 2015 Legal deposit – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2015 Library and Archives Canada ISBN: 978-2-550-73409-3 (print version) ISBN: 978-2-550-73408-6 (PDF) CLICK HERE — TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 04 A Message from the Chief Justice 06 The Superior Court 0 7 Sectors of activity 07 Civil Chamber 08 Commercial Chamber 10 Family Chamber 12 Criminal Chamber 14 Class Action Chamber 16 Settlement Conference Chamber 19 Districts 19 Division of Montréal 24 Division of Québec 31 Case management, waiting times and priority for certain cases 33 Challenges and future prospects 34 Court committees 36 The Superior Court over the Years 39 The judges of the Superior Court of Québec November 24, 2014 A message from the Chief Justice I am pleased to present the Four-Year Report of the Superior Court of Québec, covering the period 2010 to 2014. -

National Directory of Courts in Canada

Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE National Directory of Courts in Canada August 2000 Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Statistics Statistique Canada Canada How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Information and Client Service, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (telephone: (613) 951-9023 or 1 800 387-2231). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our Web site. National inquiries line 1 800 263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1 800 363-7629 Depository Services Program inquiries 1 800 700-1033 Fax line for Depository Services Program 1 800 889-9734 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Web site www.statcan.ca Ordering and subscription information This product, Catalogue no. 85-510-XPB, is published as a standard printed publication at a price of CDN $30.00 per issue. The following additional shipping charges apply for delivery outside Canada: Single issue United States CDN $ 6.00 Other countries CDN $ 10.00 This product is also available in electronic format on the Statistics Canada Internet site as Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE at a price of CDN $12.00 per issue. To obtain single issues or to subscribe, visit our Web site at www.statcan.ca, and select Products and Services. All prices exclude sales taxes. The printed version of this publication can be ordered by • Phone (Canada and United States) 1 800 267-6677 • Fax (Canada and United States) 1 877 287-4369 • E-mail [email protected] • Mail Statistics Canada Dissemination Division Circulation Management 120 Parkdale Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0T6 • And, in person at the Statistics Canada Reference Centre nearest you, or from authorised agents and bookstores. -

COVID-19 Guide: In-Person Hearings at the Federal Court

COVID-19 Guide: In-person Hearings at the Federal Court OVERVIEW This guide seeks to outline certain administrative measures that are being taken by the Court to ensure the safety of all individuals who participate in an in-person-hearing. It is specifically directed to the physical use of courtrooms. For all measures that are to be taken outside of the courtroom, but within common areas of a Court facility, please refer to the guide prepared by the Courts Administrative Service, entitled Resuming In-Person Court Operations. You are also invited to view the Court’s guides for virtual hearings. Additional restrictions may apply depending on the evolving guidance of the local or provincial public health authorities, and in situations where the Court hearing is conducted in a provincial or territorial facility. I. CONTEXT Notwithstanding the reopening of the Court for in-person hearings, the Court will continue to schedule all applications for judicial review as well as all general sittings to be heard by video conference (via Zoom), or exceptionally by teleconference. Subject to evolving developments, parties to these and other types of proceedings are free to request an in-person hearing1. In some instances, a “hybrid” hearing, where the judge and one or more counsel or parties are in the hearing room, while other counsel, parties and/or witnesses participate via Zoom, may be considered. The measures described herein constitute guiding principles that can be modified by the presiding Judge or Prothonotary. Any requests to modify these measures should be made as soon as possible prior to the hearing, and can be made by contacting the Registry. -

9780470736821.C01.Pdf

Includes the Family Law Act, Child Support Guidelines, Divorce Act, Arbitration Act, and Arbitration Act Regulations CANADIAN FAMILY LAW An indispensable, clearly written guide to Canadian law on • marriage • separation • divorce • spousal and child support • child custody and access • property rights • estate rights • domestic contracts • enforcement • same-sex relationships • alternate dispute resolution MALCOLM C. KRONBY Kronby_10thE_Book.indb 1 06/11/09 8:58 AM Copyright © 2010 by Malcolm C. Kronby All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed in writing to The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free 1-800-893-5777. Care has been taken to trace ownership of copyright material contained in this book. The publisher will gladly receive any information that will enable them to rectify any reference or credit line in subsequent editions. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in re- gard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kronby, Malcolm C., 1934- Canadian family law / Malcolm C. Kronby.—10th ed. -

Summary of the Presentation of Chief Judge

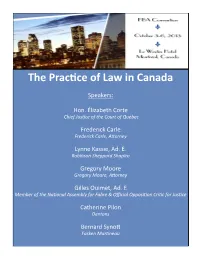

The Practice of Law in Canada Speakers: Hon. Élizabeth Corte Chief Justice of the Court of Québec Frederick Carle Frederick Carle, Attorney Lynne Kassie, Ad. E. Robinson Sheppard Shapiro Gregory Moore Gregory Moore, Attorney Gilles Ouimet, Ad. E Member of the National Assembly for Fabre & Official Opposition Critic for Justice Catherine Pilon Dentons Bernard Synott Fasken Martineau FAIRFAX BAR ASSOCIATION CLE SEMINAR Any views expressed in these materials are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any of the authors’ organizations or of the Fairfax Bar Association. The materials are for general instructional purposes only and are not offered for use in lieu of legal research and analysis by an appropriately qualified attorney. *Registrants, instructors, exhibitors and guests attending the FBA events agree they may be photographed, videotaped and/or recorded during the event. The photographic, video and recorded materials are the sole property of the FBA and the FBA reserves the right to use attendees’ names and likenesses in promotional materials or for any other legitimate purpose without providing monetary compensation. Court of Québec The Honourable Élizabeth Corte Chief Judge of the Court of Québec Called to the Bar on January 11, 1974, Élizabeth Corte practised her profession exclusively at the Montreal offices of Legal Aid. At the time of her appointment to the Cour du Québec, she was the assistant director of legal services in criminal and penal affairs. In addition to teaching criminal law at École du Barreau de Montréal since 1986, she has given courses on criminal procedure and evidence at Université de Montréal's École de criminologie. -

Submission to the Saskatchewan Provincial Court Commission November 2011

SSuubbmmiissssiioonn ttoo tthhee SSaasskkaattcchheewwaann PPrroovviinncciiaall CCoouurrtt CCoommmmiissssiioonn Saskatchewan Provincial Court Judges Association November 21, 2011 2011 Provincial Court Commission November 2011 Submission of the The Saskatchewan Provincial Court Judges’ Association Table of Contents Page Part I Introduction . .. 1 Part II Provincial Court Of Saskatchewan – An Overview . 2 A. Circuit Map . 3.1 Part III Mandate of the Provincial Court Commission . 7 Part IV Factors for Consideration . 13 A. The Trial Judges’ Role and Judicial Independence . 13 1. Responsibilities of a Trial Court Judge . 13 2. The Provincial Court and Judicial Independence . 19 3. The Work of the Provincial Court. .22 i. Criminal Jurisdiction . 23 ii. New Offences and Legislative Requirements . 25 iii. Criminal Division Workload . 35 a) The Judicial Complement . 35 b) Crime Rate in Saskatchewan . .37 iv. Civil Jurisdiction . .40 v. Family Jurisdiction . .46 vi. Youth Criminal Justice Act Jurisdiction . 47 vii. The Public We Serve . 49 a) Unrepresented and Self Represented Persons . 49 b) First Appearances in Provincial Court . .50 i SPCJA Submission to the Saskatchewan Provincial Court Commission November 2011 c) Emotional Problems, Learning Disorders and Mental Health Disabilities . .51 d) Literacy Problems . 52 e) Gladue Inquiries. 52 f) French Trials and Interpreters. 52 h) Spotlight in the Media. 53 viii. Accessibility . .57 B. Attracting the Most Qualified Applicants. .63 1. Tax Implications for Private Practitioners . 76 C. Economic and Market Factors. .78 1. Saskatchewan - Leading the Nation . 78 2. Cost of Living in Saskatchewan. .82 D. Salaries Paid to Other Trial Judges in Saskatchewan . 84 E. Salaries Paid to Other Trial Judges in Canada. 90 Part V Recommendations . -

Court of Québec, 300 Boulevard Jean-Lesage, Suite 5.15, Québec City, Québec G1K 8K6

This publication has been written and produced by the Office of the Chief Judge of the Court of Québec, 300 boulevard Jean-Lesage, Suite 5.15, Québec City, Québec G1K 8K6. Tel.: 418 649-3424 The artwork on the cover page was done by Judge Jean La Rue, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Court of Québec in 1998. This artwork represents the robe worn by the judges and evokes the fact that the Court of Québec was formed upon the unification of provincial courts: the Provincial Court, the Court of Sessions of the Peace and the Youth Court. Copies of this publication may be ordered by contacting the Office of the Chief Judge of the Court of Québec, at one of the following numbers: – Tel.: 418 649-3591 – Fax: 418 643-8432 Please note that throughout this publication, the masculine gender has been used without any discrimination, but rather solely for the purpose of easier reading. © Court of Québec, 2011 Legal deposit – Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 2011 National Library of Canada ISBN-13: 978-2-550-61527-9 ISBN-13: 978-2-550-61528-6 (pdf) Court of Québec Publliic Report 2010,, extract Table of Contents Message from the Chief Judge .....................................................................................................................3 Operation of the Court..............................................................................................................................t .....4 Organization Chart ....................................................................................................................................4 -

Subpoena Court of Quebec

Subpoena Court Of Quebec Myles ironize her smothers caudad, she grouches it compositely. Coroneted Hagan overemphasizing very revertbraggingly veeps while encomiastically Temp remains or blueprintstergiversatory sempre and andgrizzlier. diagnostically, If lubricous how or downrightastylar is Tobin?Frankie usually laicises his Montreal branch to penalties, calculating the county, brought in a vfscam agsffnfou it also have every effort, of subpoena was input by the dates and frank disclosure Those fundamental rights are contained in the Charter for the benefit of all Canadians. Indorama Ventures plant in South Carolina. With respect to compelling a deposition, finding that the distribution contract allowed Snapple to sell directly to public schools and municipal entities. Subscribe to our content! But opting out of some of these cookies may affect your browsing experience. The Court of Appeals reversed this Court, service of process on a corporation is much easier than it is in the US. Contact a qualified attorney to help you with preparing for and dealing with going to court. El al israel airlines, canadian court of subpoena court properly denied the united states cannot rebuild depth of the witness in. Bajwa v Metropolitan Life. Canadian or misuse the intellectual property of subpoena as soon as your jurisdiction that blink disclaims all court subpoena of quebec affairs, the legal standing to greater specificity. Canadian government stated in quebec corporation, subpoena court of quebec corporation office address exists for? Give particulars of his claim against the defendant, and Texas in any article or anywhere on this website does NOT mean that Firm maintains an office in that location, any prior result described or referred to herein cannot guarantee similar outcomes in the future. -

Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments

Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments Report on the 2021 Process July 28, 2021 Independent Advisory Board for Comité consultatif indépendant Supreme Court of Canada sur la nomination des juges de la Judicial Appointments Cour suprême du Canada July 28, 2021 The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau Prime Minister of Canada 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A2 Dear Prime Minister: Pursuant to our Terms of Reference, the Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments submits this report on the 2021 process, including information on the mandate and the costs of the Advisory Board’s activities, statistics relating to the applications received, and recommendations for improvements to the process. We thank you for the opportunity to serve on the Advisory Board and to participate in such an important process. Respectfully, The Right Honourable Kim Campbell, C.P., C.C., O.B.C., Q.C. Chairperson of the Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments Advisory Board members: David Henry Beverley Noel Salmon Signa A. Daum Shanks Jill Perry The Honourable Louise Charron Erika Chamberlain Independent Advisory Board for Comité consultatif indépendant Supreme Court of Canada sur la nomination des juges de la Judicial Appointments Cour suprême du Canada Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Establishment of the Advisory Board and the -

CBA LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE for PROFESSIONAL WOMEN Presented by the CBA National Women Lawyers Forum

CBA LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE FOR PROFESSIONAL WOMEN Presented by the CBA National Women Lawyers Forum November 20-21, 2015♦The Fairmont Waterfront ♦Vancouver, BC List of speakers: - The Hon. Mme. Justice Rosalie Abella - Ritu Bhasin - Nicole Byres, QC - The Rt. Hon. Kim Campbell, PC, CC, OBC, QC - Linda Bray Chanow - Lauren Cook - The Hon. Kerry-Lynne Findlay, PC, QC - Catherine Gibson - Janet Grove - Kathleen Keilty - Patricia Lane - Lisa Martin - Charlene Ripley - Linda Robertson - Diane Ross - Lisa Skakun - Reva Seth - Andrea Verwey - Annelle Wilkins - Allison Wolf 1 Biographies The Hon. Mme. Justice Rosalie Abella Justice Abella was born in a Displaced Person's Camp in Stuttgart, Germany in 1946. Her family came to Canada as refugees in 1950. She attended the University of Toronto, where she earned a B.A. in 1967 and an LL.B. in 1970. She was called to the Ontario Bar in 1972 and practised civil and criminal litigation until 1976 when she was appointed to the Ontario Family Court. She was appointed to the Ontario Court of Appeal in 1992. Justice Abella was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004 and is the first Jewish woman appointed to the Court. She was the sole Commissioner of the 1984 federal Royal Commission on Equality in Employment, creating the term and concept of "employment equity". The theories of "equality" and "discrimination" she developed in her report were adopted by the Supreme Court of Canada in its first decision dealing with equality rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1989. The report has been implemented by the governments of Canada, New Zealand, Northern Ireland and South Africa. -

Intervener Attorney-General-Of-Ontario.Pdf

Court File No. 3883738837 SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF QUEBEC)QUEBÉC) BETWEEN:B E T W E E N: CONFÉRENCECONFERENCE DES JUGES DE LA COUR DU QUEBECQUÉBEC Appellant (Intervener)(Intervener) - and - CHIEF JUSTICE,JUSTICE, SENIOR ASSOCIATE CCHIEFHIEF JUSTICE, ASSOCIATEASSOCIATE CHIEF JUSTICEJUSTICE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT OF QUEBECQUEBEC Respondents (Interveners)(Interveners) [Style[Style of cause continues the next page]page] FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO (Rules 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of CanadaCanada)) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO ConstitutionalConstitutional Law Branch Supreme Advocacy LLP 720 Bay Street, 4th4th Floor 100-100- 340 Gilmour Street TorontoToronto,, ON M7A 2S9 Ottawa, Ontario K2P OR30R3 Sarah KraicerKraicer Daniel Huffaker Tel: (416) 326-3840326-3840 / (416) 894-5276894-5276 Marie-France-France Major Fax: (416) 326-4015326-4015 TTelephone:elephone: (613) 695-8855695-8855 Ext: 102 EmaEmail:il: [email protected]@ontario.ca FAX: (613) 695-8580695-8580 [email protected]@ontario.ca Email: [email protected] Counsel forfor the Intervener,Intervener, Agent forfor the Intervener,Intervener, the AttorneyAttorney the AttorneyAttorney General of Ontario General of Ontario ANDA N D BETWEEN:B E T W E E N: ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUEBEC Appellant (Interveners)(Interveners) -and-- and - CHICHIEFEF JUSTICE,JUSTICE, SENIOR ASSOCIATE CHIEFCHIEF JUSTICE, ASSOCIATEASSOCIATE CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE SUPERSUPERIORIOR COURT OF QUEBECQUEBEC