Bijuralism: a Supreme Court of Canada Justice's Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

Western Weekly Reports

WESTERN WEEKLY REPORTS Reports of Cases Decided in the Courts of Western Canada and Certain Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada 2013-VOLUME 12 (Cited [2013] 12 W.W.R.) All cases of value from the courts of Western Canada and appeals therefrom to the Supreme Court of Canada SELECTION EDITOR Walter J. Watson, B.A., LL.B. ASSOCIATE EDITORS (Alberta) E. Mirth, Q.C. (British Columbia) Darrell E. Burns, LL.B., LL.M. (Manitoba) E. Arthur Braid, Q.C. (Saskatchewan) G.L. Gerrand, Q.C. CARSWELL EDITORIAL STAFF Cheryl L. McPherson, B.A.(HONS.) Director, Primary Content Operations Audrey Wineberg, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Product Development Manager Nicole Ross, B.A., LL.B. Supervisor, Legal Writing Andrea Andrulis, B.A., LL.B., LL.M. (Acting) Supervisor, Legal Writing Andrew Pignataro, B.A.(HONS.) Content Editor WESTERN WEEKLY REPORTS is published 48 times per year. Subscrip- Western Weekly Reports est publi´e 48 fois par ann´ee. L’abonnement est de tion rate $409.00 per bound volume including parts. Indexed: Carswell’s In- 409 $ par volume reli´e incluant les fascicules. Indexation: Index a` la docu- dex to Canadian Legal Literature. mentation juridique au Canada de Carswell. Editorial Offices are also located at the following address: 430 rue St. Pierre, Le bureau de la r´edaction est situ´e a` Montr´eal — 430, rue St. Pierre, Mon- Montr´eal, Qu´ebec, H2Y 2M5. tr´eal, Qu´ebec, H2Y 2M5. ________ ________ © 2013 Thomson Reuters Canada Limited © 2013 Thomson Reuters Canada Limit´ee NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER: All rights reserved. -

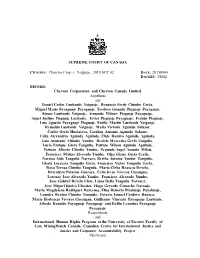

Supreme Court of Canada Judgment in Chevron Corp V Yaiguaje 2015

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Chevron Corp. v. Yaiguaje, 2015 SCC 42 DATE: 20150904 DOCKET: 35682 BETWEEN: Chevron Corporation and Chevron Canada Limited Appellants and Daniel Carlos Lusitande Yaiguaje, Benancio Fredy Chimbo Grefa, Miguel Mario Payaguaje Payaguaje, Teodoro Gonzalo Piaguaje Payaguaje, Simon Lusitande Yaiguaje, Armando Wilmer Piaguaje Payaguaje, Angel Justino Piaguaje Lucitante, Javier Piaguaje Payaguaje, Fermin Piaguaje, Luis Agustin Payaguaje Piaguaje, Emilio Martin Lusitande Yaiguaje, Reinaldo Lusitande Yaiguaje, Maria Victoria Aguinda Salazar, Carlos Grefa Huatatoca, Catalina Antonia Aguinda Salazar, Lidia Alexandria Aguinda Aguinda, Clide Ramiro Aguinda Aguinda, Luis Armando Chimbo Yumbo, Beatriz Mercedes Grefa Tanguila, Lucio Enrique Grefa Tanguila, Patricio Wilson Aguinda Aguinda, Patricio Alberto Chimbo Yumbo, Segundo Angel Amanta Milan, Francisco Matias Alvarado Yumbo, Olga Gloria Grefa Cerda, Narcisa Aida Tanguila Narvaez, Bertha Antonia Yumbo Tanguila, Gloria Lucrecia Tanguila Grefa, Francisco Victor Tanguila Grefa, Rosa Teresa Chimbo Tanguila, Maria Clelia Reascos Revelo, Heleodoro Pataron Guaraca, Celia Irene Viveros Cusangua, Lorenzo Jose Alvarado Yumbo, Francisco Alvarado Yumbo, Jose Gabriel Revelo Llore, Luisa Delia Tanguila Narvaez, Jose Miguel Ipiales Chicaiza, Hugo Gerardo Camacho Naranjo, Maria Magdalena Rodriguez Barcenes, Elias Roberto Piyahuaje Payahuaje, Lourdes Beatriz Chimbo Tanguila, Octavio Ismael Cordova Huanca, Maria Hortencia Viveros Cusangua, Guillermo Vincente Payaguaje Lusitante, Alfredo Donaldo Payaguaje Payaguaje and Delfin Leonidas Payaguaje Payaguaje Respondents - and - International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, MiningWatch Canada, Canadian Centre for International Justice and Justice and Corporate Accountability Project Interveners CORAM: McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Rothstein, Cromwell, Karakatsanis, Wagner and Gascon JJ. REASONS FOR JUDGMENT: Gascon J. (McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Rothstein, (paras. 1 to 96) Cromwell, Karakatsanis and Wagner JJ. -

Louise Arbour and Marie Henein Share Their Personal Reflections on Unconscious Bias in Litigation December 9, 2020

Louise Arbour and Marie Henein Share Their Personal Reflections on Unconscious Bias in Litigation December 9, 2020 In this transformative age when actions against unconscious bias and social injustice have swiftly gathered momentum, two legal phenoms engage in an enlightening Q & A on what this means for us as people, as a profession, and as propellers for change. Hear Louise Arbour and Marie Henein tell us how they have approached unconscious bias and how to combat it. Topics will include the following: • personal experiences with power, privilege and unconscious bias • how to prevent bias and discrimination in workplaces • bias, discrimination and underrepresentation as viewed through a judicial lens • why the existence and consequences of unconscious bias are important to the bench and bar. Speakers The Honourable Louise Arbour, C.C., G.O.Q., Senior Counsel at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP The Honourable Louise Arbour is Senior Counsel and jurist in residence at BLG in Montreal. She provides strategic advice on litigation, governance and international disputes. She is an active mentor of younger lawyers. She recently completed her mandate at the UN as Special Representative of the Secretary- General on International Migration, which led to the adoption of the Global Compact for Migration. She has also held other senior positions at the United Nations, including High Commissioner for Human Rights (2004-2008) and Chief Prosecutor for The International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda (1996 to 1999). She formerly sat as a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1999 to 2004, on the Court of Appeal for Ontario and the Supreme Court of Ontario. -

11488911.PDF (4.052Mb)

Faculté de Droit Direction des bibliothèques AVIS NOTICE L’auteur a autorisé l’Université The author has given the de Montréal à reproduire et Université de Montréal diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, permission to partially or par quelque moyen que ce soit completely reproduce and et sur quelque support que ce diffuse copies of this report or soit, et exclusivement à des fins thesis in any form or by any non lucratives d’enseignement means whatsoever for strictly et de recherche, des copies de non profit educational and ce mémoire ou de cette thèse. purposes. L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas The author and the co-authors, échéant, conservent néan- if applicable, nevertheless keep moins la liberté reconnue au the acknowledged rights of a titulaire du droit d’auteur de copyright holder to com- diffuser, éditer et utiliser mercially diffuse, edit and use commercialement ou non ce this work if they choose. Long travail. Les extraits substantiels excerpts from this work may not de celui-ci ne peuvent être be printed or reproduced in imprimés ou autrement another form without reproduits sans autorisation de permission from the author. l’auteur. L’Université ne sera The University is not aucunement responsable d’une responsible for commercial, utilisation commerciale, indus- industrial or other use of this trielle ou autre du mémoire ou report or thesis by a third party, de la thèse par un tiers, y including by professors. compris les professeurs. Université rU, de Montréal Université de Montréal Pour une constitutionnalisation du droit à -

The Social Context Education Project (SCEP) Was a Special Project of the National Judicial Institute Between 1996-2003

NATIONAL JUDICIAL INSTITUTE, CANADA THE SOCIAL CONTEXT EDUCATION PROJECT SUMMARY The Social Context Education Project (SCEP) was a special project of the National Judicial Institute between 1996-2003. The program had two phases: • Phase I concentrated on full-court education seminars in every province of Canada. These seminars were designed to create a common base of information and understanding of the relevance and applicability of social context among all judges in Canada. Over 20 programs were held involving over 1000 judges. • Phase II focused on developed skilled judicial education leaders in this area through an intensive program of judicial faculty development. Curriculum development was another focus of Phase II. Since 2003, social context has been integrated as a regular component of NJI work through adoption of the guiding principle that judicial education should always be ‘three dimensional’ (substantive law, skills development and social context awareness) and designation of a member of the senior management team responsible for social context integration. The Social Context Education Program: • Built on work initiated in Canada by the Western Judicial Education Centre • Was mandated by the Canadian Judicial Council and supported by Chief Judges. • Built from the premise that understanding social context and integrating it into judicial processes and judicial decision-making is mandated by law. • Was developed in synergy with jurisprudential developments explicitly recognizing the legitimacy of contextual inquiry in judicial decision-making. • Has proceeded on the basis that social context education is a long-term process not an inoculation. The long-term goal is integration of social context into all forms of judicial education as an automatic part of the landscape. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Superior Court of Québec 2010 2014 Activity Report

SUPERIOR COURT OF QUÉBEC 2010 2014 ACTIVITY REPORT A COURT FOR CITIZENS SUPERIOR COURT OF QUÉBEC 2010 2014 ACTIVITY REPORT A COURT FOR CITIZENS CLICK HERE — TABLE OF CONTENTS The drawing on the cover is the red rosette found on the back of the collar of the judge’s gown. It was originally used in England, where judges wore wigs: their black rosettes, which were applied vertically, prevented their wigs from rubbing against and wearing out the collars of their gowns. Photo on page 18 Robert Levesque Photos on pages 29 and 30 Guy Lacoursière This publication was written and produced by the Office of the Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Québec 1, rue Notre-Dame Est Montréal (Québec) H2Y 1B6 Phone: 514 393-2144 An electronic version of this publication is available on the Court website (www.tribunaux.qc.ca) © Superior Court of Québec, 2015 Legal deposit – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2015 Library and Archives Canada ISBN: 978-2-550-73409-3 (print version) ISBN: 978-2-550-73408-6 (PDF) CLICK HERE — TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 04 A Message from the Chief Justice 06 The Superior Court 0 7 Sectors of activity 07 Civil Chamber 08 Commercial Chamber 10 Family Chamber 12 Criminal Chamber 14 Class Action Chamber 16 Settlement Conference Chamber 19 Districts 19 Division of Montréal 24 Division of Québec 31 Case management, waiting times and priority for certain cases 33 Challenges and future prospects 34 Court committees 36 The Superior Court over the Years 39 The judges of the Superior Court of Québec November 24, 2014 A message from the Chief Justice I am pleased to present the Four-Year Report of the Superior Court of Québec, covering the period 2010 to 2014. -

National Directory of Courts in Canada

Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE National Directory of Courts in Canada August 2000 Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Statistics Statistique Canada Canada How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Information and Client Service, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (telephone: (613) 951-9023 or 1 800 387-2231). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our Web site. National inquiries line 1 800 263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1 800 363-7629 Depository Services Program inquiries 1 800 700-1033 Fax line for Depository Services Program 1 800 889-9734 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Web site www.statcan.ca Ordering and subscription information This product, Catalogue no. 85-510-XPB, is published as a standard printed publication at a price of CDN $30.00 per issue. The following additional shipping charges apply for delivery outside Canada: Single issue United States CDN $ 6.00 Other countries CDN $ 10.00 This product is also available in electronic format on the Statistics Canada Internet site as Catalogue no. 85-510-XIE at a price of CDN $12.00 per issue. To obtain single issues or to subscribe, visit our Web site at www.statcan.ca, and select Products and Services. All prices exclude sales taxes. The printed version of this publication can be ordered by • Phone (Canada and United States) 1 800 267-6677 • Fax (Canada and United States) 1 877 287-4369 • E-mail [email protected] • Mail Statistics Canada Dissemination Division Circulation Management 120 Parkdale Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0T6 • And, in person at the Statistics Canada Reference Centre nearest you, or from authorised agents and bookstores. -

Froduard Munyangabe Legal Meaning in The

Institute of Advanced Legal Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Froduard Munyangabe Legal meaning in the interpretation of multilingual legislations: Comparative analysis of Rwanda, Canada and Ireland LLM 2010-2011 LLM in Advanced Legislative Studies (ALS) S2006 1 Legal meaning in the interpretation of multilingual legislations: Comparative analysis of Rwanda, Canada and Ireland Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 2 Dedication ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Justification .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Structure ............................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 Preliminary considerations ............................................................................................... 7 2.1 Concepts ............................................................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Interpretation of Laws...................................................................................................... -

Manitoba, Attorney General of New Brunswick, Attorney General of Québec

Court File No. 38663 and 38781 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal) IN THE MATTER OF THE GREENHOUSE GAS POLLUTION ACT, Bill C-74, Part V AND IN THE MATTER OF A REFERENCE BY THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL TO THE COURT OF APPEAL UNDER THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS ACT, 2012, SS 2012, c C-29.01 BETWEEN: ATTORNEY GENERAL OF SASKATCHEWAN APPELLANT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ALBERTA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUÉBEC INTERVENERS (Title of Proceeding continued on next page) FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP Legal Services Branch, Constitutional Law Section Barristers & Solicitors 1230 - 405 Broadway Suite 2600, 160 Elgin Street Winnipeg MB R3C 3L6 Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Michael Conner / Allison Kindle Pejovic D. Lynne Watt Tel: (204) 391-0767/(204) 945-2856 Tel: (613) 786-8695 Fax: (204) 945-0053 Fax: (613) 788-3509 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for the Intervener Ottawa Agent for the Intervener -and - SASKATCHEWAN POWER CORPORATION AND SASKENERGY INCORPORATED, CANADIAN TAXPAYERS FEDERATION, UNITED CONSERVATIVE ASSOCIATION, AGRICULTURAL PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION OF SASKATCHEWAN INC., INTERNATIONAL EMISSIONS TRADING ASSOCIATION, CANADIAN PUBLIC HEALTH -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism.