Zacharias N. T S Ir P a Nl1 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUBERCULOSIS in GREECE an Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country by J

TUBERCULOSIS IN GREECE An Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country By J. B. McDOUGALL, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P. (Ed.), F.R.S.E.; Late Consultant in Tuberculosis, Greece, UNRRA INTRODUCTION In Greece, we follow the traditions of truly great men in all branches of science, and in none more than in the science of medicine. Charles Singer has rightly said - "Without Herophilus, we should have had no Harvey, and the rise of physiology might have been delayed for centuries. Had Galen's works not survived, Vesalius would have never reconstructed anatomy, and surgery too might have stayed behind with her laggard sister, Medicine. The Hippo- cratic collection was the necessary and acknowledged basis for the work of the greatest of modern clinical observers, Sydenham, and the teaching of Hippocrates and his school is still the substantial basis of instruction in the wards of a modern hospital." When we consider the paucity of the raw material with which the Father of Medicine had to work-the absence of the precise scientific method, a population no larger than that of a small town in England, the opposition of religious doctrines and dogma which concerned themselves largely with the healing art, and a natural tendency to speculate on theory rather than to face the practical problems involved-it is indeed remarkable that we have been left a heritage in clinical medicine which has never been excelled. Nearly 2,000 years elapsed before any really vital advances were made on the fundamentals as laid down by the Hippocratic School. -

A Survey of Scale Insects in Soil Samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 565: 1–28A survey (2016) of scale insects in soil samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha) 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.565.6877 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A survey of scale insects in soil samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha) Mehmet Bora Kaydan1,2, Zsuzsanna Konczné Benedicty1, Balázs Kiss1, Éva Szita1 1 Plant Protection Institute, Centre for Agricultural Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Herman Ottó u. 15 H-1022 Budapest, Hungary 2 Çukurova Üniversity, Imamoglu Vocational School, Adana, Turkey Corresponding author: Éva Szita ([email protected]) Academic editor: R. Blackman | Received 17 October 2015 | Accepted 31 December 2015 | Published 17 February 2016 http://zoobank.org/50B411DB-C63F-4FA4-8D1F-C756B304FBD7 Citation: Kaydan MB, Konczné Benedicty Z, Kiss B, Szita É (2016) A survey of scale insects in soil samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha). ZooKeys 565: 1–28. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.565.6877 Abstract In the last decades, several expeditions were organized in Europe by the researchers of the Hungarian Natural History Museum to collect snails, aquatic insects and soil animals (mites, springtails, nematodes, and earthworms). In this study, scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) specimens extracted from Hun- garian Natural History Museum soil samples (2970 samples in total), all of which were collected using soil and litter sampling devices, and extracted by Berlese funnel, were examined. From these samples, 43 scale insect species (Acanthococcidae 4, Coccidae 2, Micrococcidae 1, Ortheziidae 7, Pseudococcidae 21, Putoidae 1 and Rhizoecidae 7) were found in 16 European countries. In addition, a new species belong- ing to the family Pseudococcidae, Brevennia larvalis Kaydan, sp. -

Cataloging Service Bulletin 098, Fall 2002

ISSN 0160-8029 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/WASHINGTON CATALOGING SERVICE BULLETIN LIBRARY SERVICES Number 98, Fall 2002 Editor: Robert M. Hiatt CONTENTS Page DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING Library of Congress Rule Interpretations 2 SUBJECT CATALOGING Subdivision Simplification Progress 58 Changed or Cancelled Free-Floating Subdivisions 58 Subject Headings of Current Interest 58 Revised LC Subject Headings 59 Subject Headings Replaced by Name Headings 65 MARC Language Codes 65 Editorial postal address: Cataloging Policy and Support Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540-4305 Editorial electronic mail address: [email protected] Editorial fax number: (202) 707-6629 Subscription address: Customer Support Team, Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20541-4912 Subscription electronic mail address: [email protected] Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-51400 ISSN 0160-8029 Key title: Cataloging service bulletin Copyright ©2002 the Library of Congress, except within the U.S.A. DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RULE INTERPRETATIONS (LCRI) Cumulative index of LCRI to the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, second edition, 1998 revision, that have appeared in issues of Cataloging Service Bulletin. Any LCRI previously published but not listed below is no longer applicable and has been cancelled. Lines in the margins ( , ) of revised interpretations indicate where changes have occurred. Rule Number Page 1.0 98 11 1.0C 50 12 1.0E 69 17 1.0G 44 9 1.0H 44 9 1.1B1 97 12 1.1C 94 11 1.1D2 84 11 1.1E -

Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews

"Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews, (1882-1965)" By Maddalena Marinari University of Kansas, 2009 B.A. Istituto Universitario Orientale Submitted to the Department of History and the Faculty of The Graduate School of the University Of Kansas in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________ Dr. Jeffrey Moran, Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Gabaccia __________________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani __________________________________________ Dr. Roberta Pergher __________________________________________ Dr. Ruben Flores Date Defended: 14 December 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Maddalena Marinari certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews, (1882-1965)" Committee: __________________________________________ Dr. Jeffrey Moran, Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Gabaccia __________________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani __________________________________________ Dr. Roberta Pergher __________________________________________ Dr. Ruben Flores Date Approved: 14 December 2009 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 1: From Unwanted to Restricted (1890-1921) ………………………………………...17 Chapter 2: "The doors of America are worse than shut when they are half-way open:" The Fight against the Johnson-Reed Immigration -

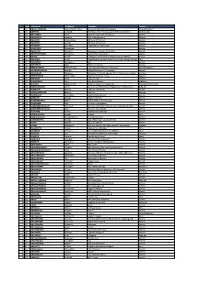

Final List EMD2015 02062015

N° Title LastName FirstName Company Country 1 Dr ABDUL RAHMAN Noorul Shaiful Fitri Universiti Malaysia Terengganu United Kingdom 2 Mr ABSPOEL Lodewijk Nl Ministry For Infrastructure And Environment Netherlands 3 Mr ABU-JABER Nizar German Jordanian University Jordan 4 Ms ADAMIDOU Despina Een -Praxi Network Greece 5 Mr ADAMOU Christoforos Ministry Of Tourism Greece 6 Mr ADAMOU Ioannis Ministry Of Tourism Greece 7 Mr AFENDRAS Evangelos Independent Consultant Greece 8 Mr AFENTAKIS Theodoros Greece 9 Mr AGALIOTIS Dionisios Vocational Institute Of Piraeus Greece 10 Mr AGATHOCLEOUS Panayiotis Cyprus Ports Authority Cyprus 11 Mr AGGOS Petros European Commission'S Representation Athens Greece 12 Dr AGOSTINI Paola Euro-Mediterranean Center On Climate Change (Cmcc) Italy 13 Mr AGRAPIDIS Panagiotis Oss Greece 14 Ms AGRAPIDIS Sofia Rep Ec In Greece Greece 15 Mr AHMAD NAJIB Ahmad Fayas Liverpool John Moores University United Kingdom 16 Dr AIFANDOPOULOU Georgia Hellenic Institute Of Transport Greece 17 Mr AKHALADZE Mamuka Maritime Transport Agency Of The Moesd Of Georgia Georgia 18 Mr AKINGUNOLA Folorunsho Nigeria Merchant Navy Nigeria 19 Mr AKKANEN Mika City Of Turku Finland 20 Ms AL BAYSSARI Paty Blue Fleet Group Lebanon 21 Dr AL KINDI Mohammed Al Safina Marine Consultancy United Arab Emirates 22 Ms ALBUQUERQUE Karen Brazilian Confederation Of Agriculture And Livesto Belgium 23 Mr ALDMOUR Ammar Embassy Of Jordan Jordan 24 Mr ALEKSANDERSEN Øistein Nofir As Norway 25 Ms ALEVRIDOU Alexandra Euroconsultants S.A. Greece 26 Mr ALEXAKIS George Region Of Crete -

Die Sprachliche Selbst- Und Fremdkonstruktion Am Beispiel Eines Arvanitischen Dorfes Griechenlands Eine Soziolinguistische Studie

Die sprachliche Selbst- und Fremdkonstruktion am Beispiel eines arvanitischen Dorfes Griechenlands Eine soziolinguistische Studie Dissertation Soziologische Abhandlung zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Sozialwissenschaften (Dr.rer.soc.) Universität Konstanz vorgelegt von Eleni Botsi September 2003 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 25 März 2004 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. Hans-Georg Soeffner 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. Hubert Knoblauch 1 VORWORT UND DANKSAGUNG....................................................................................6 EINLEITUNG ......................................................................................................................8 KAPITEL I : HISTORISCHE SKIZZE............................................................................13 1.1 Einleitung......................................................................................................................13 1.2 Die Herkunft der Albaner: Ein Streitpunkt ................................................................15 1.3 Volksnamen der Albaner .............................................................................................18 1.4 Die albanische Einwanderung nach Griechenland......................................................21 1.5 Die Entstehung der Arvanitika-Siedlungen Südgriechenlands ..................................24 1.6 Zum Ursprung des Arvanitika.....................................................................................27 KAPITEL II : METHODE ................................................................................................32 -

John S. Koliopoulos Unwanted Ally: Greece and the Great

JOHN S. KOLIOPOULOS UNWANTED ALLY: GREECE AND THE GREAT POWERS, 1939-1941 Greece’s international position and national security, from the spring of 1939 when the Axis powers initiated a policy of outright conquest in Europe until the German invasion of the country two years later, have, until recently, been examined mainly from the point of view of contemporary official Greek policy, leading thus to the development of a semi - official Greek historiography1. Most of the governing as sumptions and premises of this historiography grew out of both war time rhetoric and the post - war requirements of Greek policy, to be come in time axiomatic. Some of these assumptions and premises are: a) that Greece followed, before the' Italian attack, a neutral policy towards the great European powers; b) that the Italian attack was unprovoked ; c ) that Anglo - Greek cooperation was subsequent — and consequent — to the Italian attack ; d ) that the Greek Government, although resolved to resist a German attack, did everything to avoid it, and e) that the German invasion was unprovoked and undertaken to rescue the defeated Italians in Albania. In this paper I propose to examine these assumptions in the light of evidence newly made avail able, and see particularly whether Greece followed a really neutral policy until the Italian attack, and whether the Greco - Italian war was, until Germany decided to intervene and extinguish the poten tially dangerous conflict in the Balkans, more than a local war loosely connected with the strategical interests of Britain and Germany. Greece’s foreign relations before World War II were first put to the test in April 1939, on the occasion of the Italian occupation of Al bania. -

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe, Volume 7 the Titles Published in This Series Are Listed at Brill.Com/Yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 7

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe, Volume 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 7 Editor-in-Chief Oliver Scharbrodt Editors Samim Akgönül Ahmet Alibašić Jørgen S. Nielsen Egdūnas Račius LEIDEN | BOSTON issn 1877-1432 isbn 978-90-04-29889-7 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30890-9 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents Preface ix The Editors xv Editorial Advisers xvii List of Technical Terms xviii Islams in Europe: Satellites or a Universe Apart? 1 Jonathan Laurence Country Surveys Albania 13 Olsi Jazexhi Armenia 33 Sevak Karamyan Austria 41 Kerem Öktem Azerbaijan 62 Altay Goyushov Belarus 79 Daša Słabčanka Belgium 87 Jean-François Husson Bosnia and Herzegovina 114 Aid Smajić and Muhamed Fazlović Bulgaria 130 Aziz Nazmi Shakir Croatia 145 Dino Mujadžević -

Modern Laments in Northwestern Greece, Their Importance in Social and Musical Life and the “Making” of Oral Tradition

Karadeniz Technical University State Conservatory © 2017 Volume 1 Issue 1 December 2017 Research Article Musicologist 2017. 1 (1): 95-140 DOI: 10.33906/musicologist.373186 ATHENA KATSANEVAKI University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0003-4938-4634 Modern Laments in Northwestern Greece, Their Importance in Social and Musical Life and the “Making” of Oral Tradition ABSTRACT Having as a starting point a typical phrase -“all our songs once were KEYWORDS laments”- repeated to the researcher during fieldwork, this study aims Lament practices to explore the multiple ways in which lament practices become part of other musical practices in community life or change their Death rituals functionalities and how they contribute to music making. Though the Moiroloi meaning of this typical phrase seems to be inexplicable, nonetheless as Musical speech a general feeling it is shared by most of the people in the field. Starting from the Epirot instrumental ‘moiroloi’, extensive field research Lament-song reveals that many vocal practices considered by former researchers to Symbolic meaning be imitations of instrumental musical practices, are in fact, definite lament vocal practices-cries, embodied and reformed in different ways Collective memory in other musical contexts and serving in this way different social purposes. Furthermore, multiple functionalities of lament practices in social life reveal their transformations into songs and the ways they contribute to music making in oral tradition while at the same time confirming the flexibility of the border between lament and song established by previous researchers. Received: November 17, 2017; Accepted: December 07, 2017 95 The first attempts1 to document Greek folk songs in texts by both Greeks and foreigners included references to, or descriptions of, lament practices. -

Rivista International Internazionale Journal Di Studi of Studies Sulle Popolazioni on the People Di Origine Italiana of Italian Origin Nel Mondo in the World INDICE

gennaio-giugno 2004 28 Rivista International internazionale journal di studi of studies sulle popolazioni on the people di origine italiana of Italian origin nel mondo in the world INDICE Editoriale 5 Saggi Italiani e comunità italiane all’estero dal fascismo al secondo dopoguerra Gianfranco Cresciani Refractory Migrants. Fascist Surveillance on Italians in Australia, 1922-1943 6 Matteo Pretelli La risposta del fascismo agli stereotipi degli italiani all’estero 48 Catherine Collomp «I nostri compagni d’America»: The Jewish Labor Committee and the Rescue of Italian Antifascists, 1934-1941 66 Guido Tintori Italiani enemy aliens. I civili residenti negli Stati Uniti d’America durante la Seconda guerra mondiale 83 Stefano Luconi Bonds of Affection: Italian Americans’ Assistance for Italy 110 Sommario | Abstract | Résumé | Resumo | Extracto 124 Il teatro italiano negli Stati Uniti e in Australia Emelise Aleandri Italian-American Theatre 131 Stefania Taviano La comicità italoamericana. Il caso di Noc e Joe 152 Gaetano Rando Il teatro italoaustraliano 160 Sommario | Abstract | Résumé | Resumo | Extracto 181 Rassegna Convegni Italian Americans and the Arts & Culture (Stefano Luconi) 185 Italian Labor – American Unions: From Conflicts to Reconciliation to Leadership (Stefano Luconi) 187 Italiani nel Far West (Stefano Luconi) 190 Libri Alessandra De Michelis (a cura di), Lo sguardo di Leonilda. Una fotografa ambulante di cento anni fa. Leonilda Prato (1875-1958) (Paola Corti) 192 Linda Reeder, Widows in White: Migration and the Transformation of Rural Italian Women, Sicily 1880-1920 (Patrizia Audenino) 194 Segnalazioni 198 Riviste Segnalazioni 201 Tesi Segnalazioni 201 Editoriale Come mostrano i recenti avvenimenti, i momenti di grande crisi internaziona- le colpiscono più duramente coloro che si trovano al di fuori dei propri confi- ni nazionali. -

OPERATION ABSTENTION: the BATTLE for KASTELLORIZO, 1941 Part 1: Overview and the Australian Connection

FiliaFilia Autmn South/Spring North 2017 Edition 36 The harbour and town of Kastellorizo as seen from an Italian Airforce (Regia Aeronautica) Bomber in 1941 during World War II, prior to the bombings. Note the intact buildings & well built up neighbourhood on the Kavos promontory, the lack of shipping in the harbour as compared to earlier classic photos at the beginning of the 20th century, the walled o elds in the Hora a area and the contrasting complete absence of urban development in neighbouring Kas, Turkey, compared to today. Photo credit: Manlio Palmieri http://castellorizo.proboards. com/thread/163/february-1941-british-assault-castellorizo OPERATION ABSTENTION: THE BATTLE FOR KASTELLORIZO, 1941 Part 1: Overview and the Australian Connection. By Dr George Stabelos, Melbourne. This is one of three articles to follow in future editions of Filia. Creation yes, but more death than birth. Mankind has learned Part 2: The erce battle on the island- February 25th- 28th 1941 nothing from their forefathers, their ancestors. It is true what they say: history does repeat itself"(16). Part 3: Aftermath, legacy and implications for the future Military strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean & Aegean: Overview and background Kastellorizo’s geostrategic importance. Operation Abstention was a code name given to the British and The undertaking of Operation Abstention was the rst part of a allied assisted invasion of the Greek populated island of longstanding British desire to destabilise the Italian position on the Kastellorizo, o Greece and Turkey, from the 25th-28th February Dodecanese islands in the south-eastern part of the Aegean and 1941, during the Second World War (1-4). -

Evolution and Petroleum Potential of Western Greece

Journal of Petroleum Geology, Vol. 30(3), July 2007, pp 197-218 197 EVOLUTION AND PETROLEUM POTENTIAL OF WESTERN GREECE V. Karakitsios1,3 and N. Rigakis2 This paper reviews previous data on the geological evolution of Western Greece, with special emphasis on the petroleum potential of the Pre-Apulian zone (including new data) and the Ionian zone, the two most external portions of the Hellenide fold-and-thrust belt. From the Triassic to the Late Cretaceous, Western Greece constituted part of the southern passive margin of Tethys, and siliceous facies are widely associated with organic-carbon rich deposits. Pelagic Late Jurassic units rich in marine organic matter constitute important hydrocarbon source rocks in the pelagic– neritic Pre-Apulian zone succession. Oil–oil correlation with an Apulian zone oil sample (from Aquila, Italy) indicates similar geochemical characteristics. Thus, the significant volumes of oil generated by the rich and mature source rock intervals identified in the Pre-Apulian zone are likewise expected to be of good quality. In the Ionian zone, four organic-carbon rich intervals with hydrocarbon potential have been recorded. The tectonic history of the Pre-Apulian zone, which is characterised by the presence of large anticlines, is favourable for the formation of structural traps. By contrast, locations suitable for the entrapment of hydrocarbons in the Ionian zone are restricted to small anticlines within larger- scale synclinal structures. Hydrocarbon traps may potentially be present at the tectonic contacts between the Ionian zone and both the Pre-Apulian and Gavrovo zones. Major traps may also have been formed between the pre-evaporitic basement and the evaporite-dominated units at the base of both the Pre-Apulian and the Ionian zone successions.