View Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acres • Beaver County, Oklahoma Great Cattle Ranch and Hunting Property

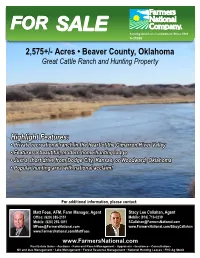

FOR SALE Serving America’s Landowners Since 1929 A-21298 2,575+/- Acres • Beaver County, Oklahoma Great Cattle Ranch and Hunting Property Highlight Features: • Private recreational ranch in the heart of the Cimarron River Valley • Features a beautiful, modern home/hunting lodge • Just a short drive from Dodge City, Kansas, or Woodward, Oklahoma • Popular hunting area with national acclaim! For additional information, please contact: Matt Foos, AFM, Farm Manager, Agent Stacy Lee Callahan, Agent Office: (620) 385-2151 Mobile: (918) 710-0239 Mobile: (620) 255-1811 [email protected] [email protected] www.FarmersNational.com/StacyCallahan www.FarmersNational.com/MattFoos www.FarmersNational.com Real Estate Sales • Auctions • Farm and Ranch Management • Appraisals • Insurance • Consultations Oil and Gas Management • Lake Management • Forest Resource Management • National Hunting Leases • FNC Ag Stock Property Description Location From Gate, Oklahoma, three miles west on Highway 64 to N 161 Road. Turn right and travel north six and a half miles then turn right onto E W 5 Road. The property is located on the left side of the road. Address: Route 1 Box 177, Gate, Oklahoma 73844 Legal All of Section 36-6N-27E CM; Lots 1,2,3 in Section 31-6N-28E E CM; SE1/4 and N1/2 of Section 35-6N-27E CM; S1/2 S1/2 of Section 26-6N-27E CM; SE1/4 and S1/2 SW1/4 of Section 25-6N-27E CM; Lots 1-4 in Section 30-6N-28E CM; NW1/4 SW1/4 of Section 29-6N-28E CM; NE1/4 and W1/2 SE1/4 of Section 2-5N-27E CM; N1/2 SE1/4 and SW1/4 SE1/4 and N1/2 and E1/2 SW1/4 of Section 1-5N-27 E CM; in Beaver County, Oklahoma Land Description Access: Two miles of frontage on E W 5 Road and a half mile frontage on N S 1610 Road Interior Access: Provided by oil and gas roads and farming access with cattle guards Fencing: Good perimeter, some updating needed on cross fencing Minerals: Selling surface rights only Cropland: 50 acres Improvements The ranch headquarters is located near the center of the property surrounded by a 50 acre heavily wooded lot. -

RANGER GAMEDAY Oct

Northwestern Oklahoma State WEEK RANGER GAMEDAY Oct. 27, 2012 Alva, Okla. 5:00 p.m. CDT 9 www.RIDERANGERSRIDE.com 2012 SCHEDULE at Ouachita Baptist* Aug. 29 << L 3-55 NORTHWESTERN Arkadelphia, Ark. OKLAHOMA STATE #5 CSU - Pueblo (1-7) Sept. 8 << L 24-41 vs. ALVA, Okla. at Truman State Sept. 15 << L 21-63 Kirksville, Mo. at UT - San Antonio JV Sept. 22 << L 3-56 AIR FORCE San Antonio, Texas (2-3) at Arkansas Tech* Sept. 29 << L 20-41 Russellville, Ark. THE MATCHUP: at East Central* Fresh off its first football victory of the NCAA Division II era, Northwestern Oklahoma State looks to continue its momentum against Air Force JV – an off-shoot of the NCAA Division I Oct. 6 << L 3-41 program that serves as a developmental squad for the varsity team. Ada, Okla. Air Force JV provides something of a mystery matchup with no official statistics and a roster SE Oklahoma State* that fluctuates from week-to-week. The famed “triple-option” offense run by the Fighting Fal- Oct. 13 << 3 p.m. con varsity may make an appearance, but don’t expect a carbon copy attack. Head Coach Steve Homecoming << ALVA Pipes is one of a handful of JV coaches who also serve as varsity assistants for Air Force. Okla. Panhandle St. THE SERIES: Oct. 20 << W 34-30 This is the first ever meeting between Northwestern and Air Force (JV or Varsity). ALVA, Okla. 2012, SO FAR: Air Force JV This has been a challenging year for the Rangers, who are making the difficult transition from Oct. -

PTCI a Part of Guymon Elementary Land Run Land Run Facts

PTCI board officers PTCI a part of Guymon remain the same. Elementary Land Run The PTCI Board of Trustees held their The gun fired at high noon, and families annual election of officers during with covered wagons raced toward free their April meeting. Lonnie Bailey plots of land to call their own. It happened was reelected to serve as President; in 1889 to settle lands in Oklahoma Territory, Rowdy McBee was reelected to serve as Vice President, and Scott and Guymon fifth graders reenacted the Martin was reelected to serve as historic event May 2. Secretary/Treasurer. Families made up of Guymon elementary “The leadership provided by our students had to run from the starting line board of trustees allows PTCI to to a plot of land, pull their stake, and take it stay progressive and always for- to claim the deed to the land. Students also ward-moving,” said Shawn Hanson, participated in a fishing tournament, tug- CEO of PTCI. of-war, and egg toss, and PTCI was there to cover it all for PTCI’s YouTube channel. PTCI See your representative on also cooked hot dogs for part of the kids’ PTCI’s website. https://www.ptci. lunches. net/about/trustees/ Streaming Workshops Forgan - June 13 | 7-9 pm Golden Agers Building Guymon - June 18 | 5-7 pm PTCI North Store Texhoma - June 28 | 12:30-2:30 pm Texhoma Community Center Contact PTCI PO Box 1188, Guymon, OK 73942 Land Run facts 580.338.2556 | ptci.net • In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison agreed to open a 1.9-million-acre section of Indi- an Territory the government had never assigned to any specific tribe. -

Geohydrology of the Oklahoma Panhandle Beaver, Cimarron And

GEOHYDROLOGY OF THE OKLAHOMA PANHANDLE, BEAVER, CIMARRON, AND TEXAS COUNTIES By D. l. Hart Jr., G. l. Hoffman, and R. L. Goemaat U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water Resources Investigation 25 -75 Prepared in cooperation with OKLAHOMA WATER RESOURCES BOARD April 1976 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Thomas Kleppe, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY v. E. McKelvey, Director For additional information write to~ U.S. Geological Survey Water Resources Division 201 N. W. 3rd Street, Room 621 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102 ii CONTENTS Pa,;e No. Factors to convert English units to metric units ..•..................... v Ab s t raet .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. I' of '" " " of .. .. ••• .. of " •, '" 7 I ntroduc t ion. ......•....•............................................... 8 Purpose and scope of investigation 8 Location and general features of the area.••..........•............ 8 Previous investigations .•.......................................... 10 Well-numbering system.•...............................•............ 10 Acknowledgments. .......•......................................... .. 13 Geology. ....•.•....................................................... .. 13 ~ Regional geology ill .. II II II oil II oil It It It "" oil 13 Geologic units and their water-bearing properties 16 Permian System...•.......................•.................... 16 Permian red beds undifferentiated...............•........ 16 Triassic System..•.•.........•...........•.................... 16 Dockt.JIn Group ~ 4 ~ #' ., of ,. '" ., # of ,. ,. .. ". 16 Jurassic -

Investing in the Future

November 2017 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF OKLAHOMA PANHANDLE STATE UNIVERSITY OPSU.edu Investing in the Future PANHANDLE STATE 1 Campus Update Anchor D gathered by the entrance to Anchor D Stadium at Panhandle State Homecoming on October 28. Aggie Athletics Sees Largest Single Gift Released by Panhandle State Campus Communications Oklahoma Panhandle State University Aggie Athletics will soon see facility upgrades at both the football stadium and the basketball arena thanks to the largest single gift in Aggie Athletic history given by Anchor D Bank and Anchor D Ranch. Panhandle State officials announced the gift on Both the stadium and the arena are expected to see Saturday, October 28 during the Homecoming Festivities. scoreboard upgrades as well. At the donors’ request, the amount was not disclosed. A historic partner with Panhandle State, Anchor D Panhandle State President Dr. Tim Faltyn was Bank, formerly The First National Bank of Texhoma, was thrilled to announce the generous donation. “This established February 22, 1906. The name reflects an area generous gift also highlights the decades long partnership ranch founded in 1878 which is similar to the time period between Panhandle State, Anchor D Bank and Anchor D this bank was opened. The ranch had headquarters in Ranch. The Freeman Family has been a blessing to this Texhoma, Goodwell, and Guymon, which is also where University for many years and we are honored to put the bank’s offices are located. Anchor D Bank is a closely their name on the stadium and arena.” held, family owned bank with quality service as the focus The gift will allow Panhandle State to modernize the of the organization. -

Economic Value of Groundwater Resources and Irrigated Agriculture in the Oklahoma Panhandle

Economic Value of Groundwater Resources and Irrigated Agriculture in the Oklahoma Panhandle Lal K. Almas Department of Agricultural Sciences West Texas A&M University WTAMU Box 60998, Canyon, Texas 79016 [email protected] W. Arden Colette Department of Agricultural Sciences West Texas A&M University WTAMU Box 60998, Canyon, Texas 79016 [email protected] Naveen C. Adusumilli Department of Agricultural Economics Texas A&M University 2124 TAMU College Station, TX 77843 [email protected] Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Southern Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Dallas, Texas, February 2-6, 2008 Partial Funding for this research was provided by Ogallala Aquifer Initiative, USDA-ARS, Bushland, Texas and Dryland Agricultural Institute, West Texas A&M University, Canyon, Texas Copyright 2008 by Lal Almas, Arden Colette, and Naveen Adusumilli. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Economic Value of Groundwater Resources and Irrigated Agriculture in the Oklahoma Panhandle. Lal Almas, Arden Colette, and Naveen Adusumilli, West Texas A&M University An economic optimization model was developed using available groundwater resources in the Oklahoma Panhandle to estimate value of water for irrigated agriculture in the area. The model will serve as policy tool to analyze alternative water management strategies and conservation programs to assess the economic impact of depleting Ogallala Aquifer. Economic Value of Groundwater Resources and Irrigated Agriculture in the Oklahoma Panhandle Abstract: An economic optimization model for a sixty years planning horizon is developed using available groundwater resources in the Oklahoma Panhandle. -

Vol. 35 No. 1 the Seal of Cimarron Territory by the Editor

Vol. 35 No. 1 The Seal of Cimarron Territory by the Editor ------------------------------------------ 2 History of No-Man’s Land by Morris L. Wardell ------------------------------------- 11 Shade’s Well by Laura V. Hammer ------------------------------------------------------ 34 Memoirs of Oklahoma by Kittie M. Harvey ------------------------------------------- 41 Judge Albert C. Hunt by Judge N.B. Johnson ------------------------------------------- 53 The Butterfield Overland Mail One Hundred Years Ago By Muriel H. Wright --------------------------------------------------------------- 55 Dr. and Mrs. Richard Moore Crain by Carolyn Thomas Foreman ------------------- 72 Health Conditions in Indian Territory, 1830 to Civil War By Bernice Norman Crockett ---------------------------------------------------- 80 Notes and Documents ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 91 Book Reviews ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 110 Minutes -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 118 THE SEAL OF CIMARRON TERRITORY The original Seal of Cimarron Territory, reproduced1 on the front cover of this number of The Chronicles was lost more than fifty years ago, leaving its existence only a tradition in Oklahoma history: The last paper bearing an impression of the Seal, a perfect impress on gold leaf, is in the margin of a letter written under the heading, ' ' Off ice of Dyke Ballinger, County Attorney, Beaver, Oklahoma, ? ' as follows -

Literature on the Vegetation of Oklahoma! RALPH W· KELTING, Unberlltj of Tulia, Tulia Add WJL T

126 PROCEEDINGS OF THE OKLAHOMA Literature on the Vegetation of Oklahoma! RALPH W· KELTING, UnberlltJ of Tulia, Tulia aDd WJL T. PENFOUND, UnlYenlty of Oklahoma, Norman The original stimulus tor this bibliographic compilation on the vegeta tion of Oklahoma came from Dr. Frank Egler, Norfolk, Connecticut, who is sponsoring a series ot such papers for aU the states of the country. Oklahoma is especially favorable for the study· of vegetation since it is a border state between the cold temperate North and the warm temperature South, and between the arid West and the humid East. In recognition of the above climatic differences, the state has been divided into seven sec tions. The parallel of 35 degrees, 30 minutes North Latitude has been utiUzed to divide the state into northern and southern portions. The state has been further divided into panhandle, western, central, and eastern sections, by the use of the following meridians: 96 degrees W., 98 degrees ·W., and 100 degrees W. In all cases, county lines have been followed so that counties would not be partitioned between two or more sections. The seven sections are as follows: Panhandle, PH; N9rthwest, NW; Southwest, SW; North Central, NC; South Central, SC; Northeast, NE; and Southeast, SE (Figure 1). The various sections of the state have unique topographic features ot interest to the student of vegetation. These sections and included topo graphic features are as tollows: Panhandle: Black Mesa, high plains, playas (wet weather ponds); Northwest: Antelope Ht1Is, Glass Mountains, gypsum hUls, sand desert, Waynoka Dunes, salt plains, Great Salt Plains Reservoir; Southwest: gypsum hills, Wichita Mountains, Altus-Lugert Reservoir; North Central: redbed plains, sandstone hills, prairie plains; South Central: redbed plains, sandstone hUls, Arbuckle Mountains, Lake Texoma; Northeast: Ozark Plateau, Grand Lake;. -

Oklahoma State System of Higher Education Overview

A guide to the history, organization and operation of the State System OKLAHOMA STATE REGENTS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION Front row, left to right: Assistant Secretary Gen. Toney Stricklin, Lawton; Vice Chair Mike C. Turpen, Oklahoma City; Chairman James D. “Jimmy” Harrel, Leedey; Chancellor Glen D. Johnson; Secretary John Massey, Durant Back row, left to right: Ronald H. White, M.D., Oklahoma City; Marlin “Ike” Glass Jr., Newkirk; Joseph L. Parker Jr.,Tulsa; Jay Helm, Tulsa; Ann Holloway, Ardmore. This publication is issued by the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, as authorized by 70 O.S. 2001, Section 3206. Copies have not been printed but are available through the agency website at www.okhighered.org. Two printout copies have been deposited with the Publications Clearinghouse of the Oklahoma Department of Libraries.. Cover photos, left to right: Cameron University, Southeastern Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma City Community College. 2 PART ONE–THE STATE SYSTEM Part One–The State System The Oklahoma State System of Higher Education is the regional universities, one public liberal arts state’s legal structure for providing public education at the university and 12 community colleges – and 11 collegiate level. It is a coordinated system of colleges and constituent agencies and two university centers. The universities located throughout the state. State System is coordinated by the Oklahoma State The State System is comprised of 25 colleges and Regents for Higher Education, and each institution universities – including two research -

Salt Karst and Collapse Structures in the Anadarko Basin of Oklahoma and Texas

SALT KARST AND COLLAPSE STRUCTURES IN THE ANADARKO BASIN OF OKLAHOMA AND TEXAS Kenneth S. Johnson Oklahoma Geological Survey, 1321 Greenbriar Dr., Norman, OK 73072, USA, [email protected] Abstract low-subsurface geology in the Anadarko Basin must Permian bedded salt is widespread in the Anadarko consider the influence of subsurface salt karst on the Basin of western Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle, structure and distribution of overlying rocks. where partial or total dissolution of the shallowest salt in some areas has resulted in subsidence and/or collapse of Introduction overlying strata. Groundwater has locally dissolved these The current study summarizes years of investigations of salts at depths of 10–250 m. The distribution (presence salt karst and resultant collapse features in and around or absence) of salt-bearing units, typically 80–150 m the Anadarko Basin of western Oklahoma and the Texas thick, is confirmed by interpretation of geophysical logs Panhandle. These investigations have involved integrated of many petroleum tests and a few scattered cores. Salt studies of: 1) the subsurface distribution and thickness of dissolution by ground water is referred to as “salt karst.” Permian salt beds; and 2) field studies to identify areas where outcropping strata are disrupted and disturbed. Chaotic structures, collapse features, breccia pipes, and other evidence of disturbed bedding are present Subsurface studies have been carried out mainly by in Permian, Cretaceous, and Tertiary strata that overly recognition of salt and associated strata on electric logs areas of salt karst. The dip of Permian and post-Permian (also known as “geophysical logs”) of oil and gas tests, strata in the region normally is less than one degree, as well as examination of several cores of salt units in mainly towards the axis of the Anadarko Basin. -

Oklahoma Research Outline

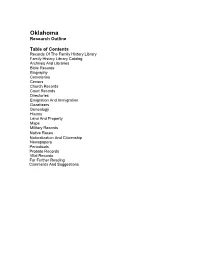

Oklahoma Research Outline Table of Contents Records Of The Family History Library Family History Library Catalog Archives And Libraries Bible Records Biography Cemeteries Census Church Records Court Records Directories Emigration And Immigration Gazetteers Genealogy History Land And Property Maps Military Records Native Races Naturalization And Citizenship Newspapers Periodicals Probate Records Vital Records For Further Reading Comments And Suggestions RESEARCH OUTLINE Oklahoma This outline describes major sources of information Oklahoma City, OK 73105-3298 about families from Oklahoma. As you read this Telephone: 405-521-2502, 800-522-8116 outline, study the United States Research Outline Fax: 405-525-7804 (30972), which will help you understand terminology Internet: www.odl.state.ok.us and the contents and uses of genealogical records. The Oklahoma Department of Libraries includes two RECORDS OF THE FAMILY areas of particular interest to genealogists: the HISTORY LIBRARY Oklahoma Room and the State Archives Division. The Oklahoma Room houses printed materials, while The Family History Library has many of the records the State Archives Division maintains Oklahoma listed in this outline. The major holdings include government records and other historical documents. biographies, cemetery records, census records, court records, vital records, and some American Indian • National Archives—Southwest Region records. 501 West Felix Street, Building 1 Some of the sources described in this outline list the Fort Worth, TX 76115-3405 Family History Library's book, microfilm, and Telephone 817-331-5620 microfiche numbers. These are preceded by FHL, the Fax 817-334-5621 abbreviation for Family History Library. These Internet: www.archives.gov/southwest/ numbers may be used to locate materials in the library Mailing address: and to order microfilm and microfiche at Family P.O. -

Institutional Overview, December 1998

INSTITUTIONAL IMPACT: CITIZENS' COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS (Information provided by Oklahoma colleges and universities) TECHNOLOGY ð Northeastern State University is expanding efforts to reach potential students through offering selected courses via interactive television to several sites in northeastern Oklahoma. NSU currently offers courses at Tahlequah, Muskogee, Tulsa, Claremore, Poteau and Miami. In the spring 1999 semester, selected upper division courses will be offered at Pryor and Bartlesville. Additional courses are being offered at Rogers University–Claremore, including distance course delivery, to assist, as directed by the State Regents, with the transition to a four-year state supported institution. ð Ardmore Higher Education Center receives and/or transmits 33 interactive classes each semester. AHEC provides a classroom facilitator for all interactive classes as well as proctoring, Internet and E-mail access, advisement, and library facilities and materials. ð Redlands Community College offers interactive educational television in Deer Creek- Lamont, Fort Cobb, Oklahoma City (through the downtown consortium), Kingfisher, Mulhall-Orlando and Ringwood. Most sites offer these classes concurrently to high school seniors but usually make them available to other eligible students. The classes are usually part of a core curriculum. ð Redlands Community College offers off-campus classes in Fort Cobb, Kingfisher, Minco, Mustang, Okarche, Piedmont, Watonga and Yukon. These RCC courses are taught by live, in-person Redlands instructors