“The Lion of the Land”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acres • Beaver County, Oklahoma Great Cattle Ranch and Hunting Property

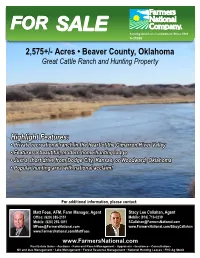

FOR SALE Serving America’s Landowners Since 1929 A-21298 2,575+/- Acres • Beaver County, Oklahoma Great Cattle Ranch and Hunting Property Highlight Features: • Private recreational ranch in the heart of the Cimarron River Valley • Features a beautiful, modern home/hunting lodge • Just a short drive from Dodge City, Kansas, or Woodward, Oklahoma • Popular hunting area with national acclaim! For additional information, please contact: Matt Foos, AFM, Farm Manager, Agent Stacy Lee Callahan, Agent Office: (620) 385-2151 Mobile: (918) 710-0239 Mobile: (620) 255-1811 [email protected] [email protected] www.FarmersNational.com/StacyCallahan www.FarmersNational.com/MattFoos www.FarmersNational.com Real Estate Sales • Auctions • Farm and Ranch Management • Appraisals • Insurance • Consultations Oil and Gas Management • Lake Management • Forest Resource Management • National Hunting Leases • FNC Ag Stock Property Description Location From Gate, Oklahoma, three miles west on Highway 64 to N 161 Road. Turn right and travel north six and a half miles then turn right onto E W 5 Road. The property is located on the left side of the road. Address: Route 1 Box 177, Gate, Oklahoma 73844 Legal All of Section 36-6N-27E CM; Lots 1,2,3 in Section 31-6N-28E E CM; SE1/4 and N1/2 of Section 35-6N-27E CM; S1/2 S1/2 of Section 26-6N-27E CM; SE1/4 and S1/2 SW1/4 of Section 25-6N-27E CM; Lots 1-4 in Section 30-6N-28E CM; NW1/4 SW1/4 of Section 29-6N-28E CM; NE1/4 and W1/2 SE1/4 of Section 2-5N-27E CM; N1/2 SE1/4 and SW1/4 SE1/4 and N1/2 and E1/2 SW1/4 of Section 1-5N-27 E CM; in Beaver County, Oklahoma Land Description Access: Two miles of frontage on E W 5 Road and a half mile frontage on N S 1610 Road Interior Access: Provided by oil and gas roads and farming access with cattle guards Fencing: Good perimeter, some updating needed on cross fencing Minerals: Selling surface rights only Cropland: 50 acres Improvements The ranch headquarters is located near the center of the property surrounded by a 50 acre heavily wooded lot. -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers the Real Wild West Writings

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers The Real Wild West Rev. July 2013 Writings 1:1 Typed draft book proposals, overviews and chapter summaries, prologue, introduction, chronologies, all in several versions. Letter from Wallis to Robert Weil (St. Martin’s Press) in reference to Wallis’s reasons for writing the book. 24 Feb 1990. 1:2 Version 1A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 19p. 1:3 Version 1B, 28p. 1:4 Version 1C, 75p. 1:5 Version 2A, 37p. 1:6 Version 2B, 56p. 1:7 Version 2C, marked as final draft, circa 12 Dec 1990. 56p. 1:8 Version 3A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen. The Story of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Empire…” 55p. 1:9 Version 3B, 46p. 1:10 Version 4: “The Read Wild West. Saturday’s Heroes: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 37p. 1:11 Version 5: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the 101 Ranch.” 8p. 1:12 Version 6A: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the Miller Brothers and the 101 Ranch.” 25p. 1:13 Version 6B, 4p. 1:14 Version 6C, 26p. 1:15 Typed draft list of sidebars and songs, 2p. Another list of proposed titles of sidebars and songs, 6p. 1:16 Introduction, a different version from the one used in Version 1 draft of text, 5p. 1:17 Version 1: “The Hundred and 101. The True Story of the Men and Women Who Created ‘The Real Wild West.’” Early typed draft text with handwritten revisions and notations. Includes title page, Dedication, Epigraph, with text and accompanying portraits and references. -

Independent Freedpeople of the Five Slaveholding Tribes

Anderson 1 “On the Forty Acres that the Government Give Me”1: Independent Freedpeople of the Five Slaveholding Tribes as Landholders, Indigenous Land Allotment Policy, and the Disruption of Racial, Gender, and Class Hierarchies in Jim Crow Oklahoma Keziah Anderson Undergraduate Senior Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 15th, 2020 Seminar Advisor: Professor George Chauncey Second Reader: Professor Celia Naylor 1 Kiziah Love, interview with Jessie R. Ervin, spring 1937, Colbert, OK, in The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives, ed. T. Lindsay Baker and Julie Philips Baker (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 262. See Appendix 6 for a full transcript of Kiziah Love’s slave narrative. © 2020 Anderson 2 - Notice - None of the work included in this document may be cited or quoted without express written permission from the author. © 2020 Anderson 3 - Table of Contents - Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5-15 Chapter 1: “You’ve an Indian Not a Negro”: Racecraft, 15-36 Land Allotment Policy, and Class Inequalities in Post-Allotment and Post-Statehood Oklahoma Racecraft and Land Use in the Pre-Allotment Period 15 Racecraft, Blood Quantum, and Ideology in the Jim Crow South & Indian Territory 18 Racecraft in the Allotment Process: Blood Quanta, One-Drop-of-Blood Rules, and Land Land Allotments, Indigeneity, and Racecraft in Post-Statehood Oklahoma 25 Chapter 2: The Reshaping of Gender in the Post-Allotment and 38-51 Post-Statehood Period: Independent Freedwomen Landowners, the (Re)Establishment of Black Infrastructure, and -

Oklahoma Territory 1889-1907

THE DIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SOME ASPECTS OF LIFE IN THE "LAND OP THE PAIR GOD"; OKLAHOMA TERRITORY, 1889=1907 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY BY BOBBY HAROLD JOHNSON Norman, Oklahoma 1967 SOME ASPECTS OP LIFE IN THE "LAND OF THE FAIR GOD"; OKLAHOMA TERRITORY, 1889-1907 APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITT If Jehovah delight in us, then he will bring us into this land, and give it unto us; a land which floweth with milk and honey. Numbers li^sS I am boundfor the promised land, I am boundfor the promised land; 0 who will come and go with me? 1 am bound for the promised land. Samuel Stennett, old gospel song Our lot is cast in a goodly land and there is no land fairer than the Land of the Pair God. Milton W, Reynolds, early Oklahoma pioneer ill PREFACE In December, 1892, the editor of the Oklahoma School Herald urged fellow Oklahomans to keep accurate records for the benefit of posterity* "There is a time coming, if the facts can be preserved," he noted, "when the pen of genius and eloquence will take hold of the various incidents con nected with the settlement of what will then be the magnifi» cent state of Oklahoma and weave them into a story that will verify the proverb that truth is more wonderful than fic tion." While making no claim to genius or eloquence, I have attempted to fulfill the editor's dream by treating the Anglo-American settlement of Oklahoma Territory from 1889 to statehood in 1907» with emphasis upon social and cultural developments* It has been my purpose not only to describe everyday life but to show the role of churches, schools, and newspapers, as well as the rise of the medical and legal professions* My treatment of these salient aspects does not profess to tell the complete story of life in Oklahoma. -

Cherokees in Arkansas

CHEROKEES IN ARKANSAS A historical synopsis prepared for the Arkansas State Racing Commission. John Jolly - first elected Chief of the Western OPERATED BY: Cherokee in Arkansas in 1824. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum LegendsArkansas.com For additional information on CNB’s cultural tourism program, go to VisitCherokeeNation.com THE CROSSING OF PATHS TIMELINE OF CHEROKEES IN ARKANSAS Late 1780s: Some Cherokees began to spend winters hunting near the St. Francis, White, and Arkansas Rivers, an area then known as “Spanish Louisiana.” According to Spanish colonial records, Cherokees traded furs with the Spanish at the Arkansas Post. Late 1790s: A small group of Cherokees relocated to the New Madrid settlement. Early 1800s: Cherokees continued to immigrate to the Arkansas and White River valleys. 1805: John B. Treat opened a trading post at Spadra Bluff to serve the incoming Cherokees. 1808: The Osage ceded some of their hunting lands between the Arkansas and White Rivers in the Treaty of Fort Clark. This increased tension between the Osage and Cherokee. 1810: Tahlonteeskee and approximately 1,200 Cherokees arrived to this area. 1811-1812: The New Madrid earthquake destroyed villages along the St. Francis River. Cherokees living there were forced to move further west to join those living between AS HISTORICAL AND MODERN NEIGHBORS, CHEROKEE the Arkansas and White Rivers. Tahlonteeskee settled along Illinois Bayou, near NATION AND ARKANSAS SHARE A DEEP HISTORY AND present-day Russellville. The Arkansas Cherokee petitioned the U.S. government CONNECTION WITH ONE ANOTHER. for an Indian agent. 1813: William Lewis Lovely was appointed as agent and he set up his post on CHEROKEE NATION BUSINESSES RESPECTS AND WILL Illinois Bayou. -

The Osage Nation, the Midnight Rider, and the EPA

CLEAN MY LAND: AMERICAN INDIANS, TRIBAL SOVEREIGNTY, AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY by RAYMOND ANTHONY NOLAN B.A., University of Redlands, 1998 M.A., St. Mary’s College of California, 2001 M.A., Fort Hays State University, 2007 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2015 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the Isleta Pueblos of central New Mexico, the Quapaw tribe of northeast Oklahoma, and the Osage Nation of northcentral Oklahoma, and their relationship with the federal government, and specifically the Environmental Protection Agency. As one of the youngest federal agencies, operating during the Self-Determination Era, it seems the EPA would be open to new approaches in federal Indian policy. In reality, the EPA has not reacted much differently than any other historical agency of the federal government. The EPA has rarely recognized the ability of Indians to take care of their own environmental problems. The EPA’s unwillingness to recognize tribal sovereignty was no where clearer than in 2005, when Republican Senator James Inhof of Oklahoma added a rider to his transportation bill that made it illegal in Oklahoma for tribes to gain primary control over their environmental protection programs without first negotiating with, and gaining permission of, the state government of Oklahoma. The rider was an erosion of the federal trust relationship with American Indian tribes (as tribes do not need to heed state laws over federal laws) and an attack on native ability to judge tribal affairs. -

SEQUOYA.Ii Constitu'tional Conveifflon 11

THE SEQUOYA.Ii CONSTITu'TIONAL CONVEifflON 11 THE SEQUOYAH CONSTITUTI OKAL CONVE?lTI ON AMOS DeZELL MAX'wELL,, Bachelor or Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillwater, Ok1ahana 191+8 Submitted to the Department of History Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Part1a1 Fu:l.f'illment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF AR!S 195'0 111 OKLAHOMA '8BICULTUltAL & MlCHANICAL COLLE&I LIBRARY APR 241950 APPROVED Bia ) 250898 iv PREl'.lCE the Sequoy-ah Constitutional. Convention was held 1n Husk-0gee, Indian ferri to17, 1n. the aUBDller of 1905. It was the culminating event of a seriea ot eol.orrul occasions in the history or the .Five Civllized. Tribes. It was there that the deseendanta of those who made the trek west seventy-:f'ive years earlier sat with white men to vr1 te a eharter tor a new state.. They wrote a con st1tution, but it was never used as a charter tor a State or Sequo,yah. This work, which is primarily a stud,y or that convention and tbe reasons for its being called and its results, was undertaken at the suggestion of..,- father, Harold K. Max.well, in August, 1948. It has been carried to a conclusion through the a.id of a number o! persons, chief' among them being my wife, Betty Jo Max well. The need tor this study is a paramount one. Other than copies of the )(Q§koga f!l91P1J, the.re are no known records or the convention. Because much of the proceedings were in one or more Indian tongues there are some gaps in the study other than those due to the laek ot records,. -

The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters 2015 The iC vil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory Bradley R. Clampitt Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Clampitt, Bradley R., "The ivC il War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory" (2015). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 311. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/311 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory Buy the Book Buy the Book The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory Edited and with an introduction by Bradley R. Clampitt University of Nebraska Press Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2015 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska A portion of the introduction originally appeared as “ ‘For Our Own Safety and Welfare’: What the Civil War Meant in Indian Territory,” by Bradley R. Clampitt, in Main Street Oklahoma: Stories of Twentieth- Century America edited by Linda W. Reese and Patricia Loughlin (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), © 2013 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory / Edited and with an introduction by Bradley R. -

POSTAL BULLET7N PUMJSWD SINM MARCH 4,1880 PB 21850-Svnmhii 16,1993 OCT 1 11993

P 1.3: 21850 POSTAL BULLET7N PUMJSWD SINM MARCH 4,1880 PB 21850-SvnMHii 16,1993 OCT 1 11993 CONTENTS f«^e I |i pr-s«s Risip^/f^? y M ^&k fiip^fE^rl |! I! H |Nft Wif Treasury Department Checks Administrative Services ^^^OO^S^D October Social Security benefit checks nor- 1994 Year Type for Hand Stamp and Canceling Machines 2 ' Credit Card Policies and Procedures (Handbook AS-709 Revision) 2 mal|Y delivered on the third of the month are Issuance of Management Instructions 1 scheduled for delivery on Friday, October 1. The Customer Services envelopes will bear the legend: AIDS Awareness Postage Stamp 6 Postmaster: Requested delivery date is Customer Satisfaction Posters and Standup Talks 9 ^ _»u Mai) A|ert ;, 8 tne 1st daY of tne month. Missing Children Poster 37 Civil Service annuity and Railroad Retirement National Consumers Week 3 checks are scheduled for delivery on the normal Treasury Department Checks 1 . ,. x _.. _ A . * , Domestic Mail delivery date, Friday, October 1. The envelopes Authorizations to Prepare Mail on Pallets (Correction) 15 wil1bea r the legend: Conditions Applied to Mail Addressed to Military Post Offices Overseas 16 Postmaster: Requested delivery date is Express Mail Security Measures,(DMMT Correction) 12 the 1 st day of the month or Flat Mail Barcodmg—85 Percent Qualification 13 ' Metered Stamp Barcode Errors 13 the first delivery date there- Postage Stamp Conversions (DMM Revision) 11 after. Revised Post Office to Addressee Express Mail Label 14 Soda| Securjt benefjt checks are ^^^^ Special Cancellations 13 ' United States Navy: Change in Mailing Status 10 for delivery on the normal delivery date, Fnday, Fraud Alerts October 1. -

Seal of the Cherokee Nation

Chronicles of Ohhorna SEAL OF THE CHEROKEE NATION A reproduction in colors of the Seal of the Cherokee Nation appears on the front coyer of this summer number of The Chronicles, made from the original painting in the Museum of the Oklahoma Historical Society.' The official Cherokee Seal is centered by a large seven-pointed star surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves, the border encircling this central device bearing the words "Seal of the Cherokee Nation" in English and seven characters of the Sequoyah alphabet which form two words in Cherokee. These seven charactem rspresenting syllables from Sequoyah's alphabet are phonetically pronounced in English ' ' Tw-la-gi-hi A-ye-li " and mean " Cherokee Nation" in the native language. At the lower part of the circular border is the date "Sept. 6, 1839," that of the adoption of the Constitution of the Cherokee Nation, West. Interpretation of the de~icein this seal is found in Cherokee folklore and history. Ritual songs in certain ancient tribal cere- monials and songs made reference to seven clans, the legendary beginnings of the Cherokee Nation whose country early in the historic period took in a wide area now included in the present eastern parts of Tennessee and Kentucky, the western parts of Virginia and the Carolinas, as well as extending over into what are now northern sections of Georgia and Alabama. A sacred fire was kept burning in the "Town House" at a central part of the old nation, logs of the live oak, a hardwood timber in the region, laid end to end to keep the fire going. -

RANGER GAMEDAY Oct

Northwestern Oklahoma State WEEK RANGER GAMEDAY Oct. 27, 2012 Alva, Okla. 5:00 p.m. CDT 9 www.RIDERANGERSRIDE.com 2012 SCHEDULE at Ouachita Baptist* Aug. 29 << L 3-55 NORTHWESTERN Arkadelphia, Ark. OKLAHOMA STATE #5 CSU - Pueblo (1-7) Sept. 8 << L 24-41 vs. ALVA, Okla. at Truman State Sept. 15 << L 21-63 Kirksville, Mo. at UT - San Antonio JV Sept. 22 << L 3-56 AIR FORCE San Antonio, Texas (2-3) at Arkansas Tech* Sept. 29 << L 20-41 Russellville, Ark. THE MATCHUP: at East Central* Fresh off its first football victory of the NCAA Division II era, Northwestern Oklahoma State looks to continue its momentum against Air Force JV – an off-shoot of the NCAA Division I Oct. 6 << L 3-41 program that serves as a developmental squad for the varsity team. Ada, Okla. Air Force JV provides something of a mystery matchup with no official statistics and a roster SE Oklahoma State* that fluctuates from week-to-week. The famed “triple-option” offense run by the Fighting Fal- Oct. 13 << 3 p.m. con varsity may make an appearance, but don’t expect a carbon copy attack. Head Coach Steve Homecoming << ALVA Pipes is one of a handful of JV coaches who also serve as varsity assistants for Air Force. Okla. Panhandle St. THE SERIES: Oct. 20 << W 34-30 This is the first ever meeting between Northwestern and Air Force (JV or Varsity). ALVA, Okla. 2012, SO FAR: Air Force JV This has been a challenging year for the Rangers, who are making the difficult transition from Oct. -

Fire History in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

Hum Ecol DOI 10.1007/s10745-013-9571-2 Fire History in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma Michael C. Stambaugh & Richard P. Guyette & Joseph Marschall # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Abstract The role of humans in historic fire regimes has Introduction received little quantitative attention. Here, we address this inadequacy by developing a fire history in northeastern Throughout North America the quantitative association be- Oklahoma on lands once occupied by the Cherokee tween historic fire regimes and humans has been limited by Nation. A fire event chronology was reconstructed from the quality and availability of data on Native American pop- 324 tree-ring dated fire scars occurring on 49 shortleaf pine ulations and their many fire cultures (Delcourt and Delcourt (Pinus echinata) remnant trees. Fire event data were exam- 1997). Fire history information has provided increased per- ined with the objective of determining the relative roles of spective on fire regimes and baseline data applicable to un- humans and climate over the last four centuries. Variability derstanding the ecology and management of fire and forests in the fire regime appeared to be significantly influenced by (Rudis and Skinner 1991;Lafon2005; Abrams and Nowacki human population density, culture, and drought. The mean 2008). Compared to these applications rarely have fire history fire interval (MFI) within the 1.2 km2 study area was data been used to gain perspective on human ecology (Kaye 7.5 years from 1633 to 1731 and 2.8 years from 1732 to and Swetnam 1999;Guyetteet al. 2002;Fuléet al. 2011). 1840. Population density of Native American groups includ- In the last decade there has been increased interest in ing Cherokee was significantly correlated (r=0.84) with the documenting the fire history of Oklahoma’s diverse vegeta- number of fires per decade between 1680 and 1880.