Anticraving Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorder: a Clinical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Citicoline in the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury

pharmaceuticals Review Role of Citicoline in the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury Julio J. Secades Medical Department, Ferrer, 08029 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Abstract: Head injury is among the most devastating types of injury, specifically called Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). There is a need to diminish the morbidity related with TBI and to improve the outcome of patients suffering TBI. Among the improvements in the treatment of TBI, neuroprotection is one of the upcoming improvements. Citicoline has been used in the management of brain ischemia related disorders, such as TBI. Citicoline has biochemical, pharmacological, and pharmacokinetic characteristics that make it a potentially useful neuroprotective drug for the management of TBI. A short review of these characteristics is included in this paper. Moreover, a narrative review of almost all the published or communicated studies performed with this drug in the management of patients with head injury is included. Based on the results obtained in these clinical studies, it is possible to conclude that citicoline is able to accelerate the recovery of consciousness and to improve the outcome of this kind of patient, with an excellent safety profile. Thus, citicoline could have a potential role in the management of TBI. Keywords: CDP-choline; citicoline; pharmacological neuroprotection; brain ischemia; traumatic brain injury; head injury Citation: Secades, J.J. Role of 1. Introduction Citicoline in the Management of Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is among the most devastating types of injury and can Traumatic Brain Injury. result in a different profile of neurological and cognitive deficits, and even death in the most Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 410. -

Eletriptan Smpc

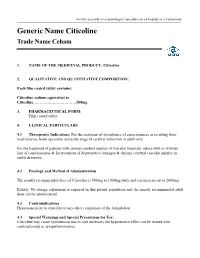

For the use only of a neurologist/ specialist or a Hospital or a Laboratory Generic Name Citicoline Trade Name Ceham 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT: Citicoline 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION: Each film coated tablet contains: Citicoline sodium equivalent to Citicoline……………………………500mg 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM: Film coated tablet 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic Indications: For the treatment of disturbance of consciousness as resulting from head injuries, brain operation and acute stage of cerebral infarction in adult only. For the treatment of patients with serious cerebral injuries of vascular traumatic nature with or without loss of consciousness & for treatment of degenerative damages & chronic cerebral vascular injuries in senile dementia. 4.2 Posology and Method of Administration The usually recommended dose of Citicoline is 500mg to 1000mg daily and can increase up to 2000mg. Elderly: No dosage adjustment is required in this patient population and the usually recommended adult dose can be administered. 4.3 Contraindications Hypersensitivity to citicoline or any other component of the formulation 4.4 Special Warnings and Special Precautions for Use: Citicoline may cause hypotension and in case necessary the hypotensive effect can be treated with corticosteroids or sympathomimetics. 4.5 Interaction with Other Medicinal Products and Other Forms of Interaction: Citicoline must not be used with medicines containing meclophenoxates (or centrophenoxine). Citicoline increases the effects of L-dopa. 4.6 Fertility, Pregnancy and Lactation There are no adequate and well controlled studies of citicoline during pregnancy and lactation. Citicoline should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. -

More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder

News & Analysis Medical News & Perspectives More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder Jeff Lyon hirteen years have passed since the Raye Z. Litten, PhD, acting director of the ment for AUD were actually prescribed an US Food and Drug Administration NIAAA’s Division of Medications Develop- AUD medication. T (FDA) last approved a new medica- ment and principal investigator of the trial, It is a complicated problem, says John tion to help the nation’s millions of people says the agency is “excited.” Rotrosen, MD, a psychiatrist and addiction withalcoholusedisorder(AUD)stopormod- Nevertheless, the science of alcohol ad- specialist at New York University School of erate their drinking. diction has seen its share of medicines that Medicine. “To a large extent primary care Only 3 such formulations exist, and 1, failed to live up to their early promise dur- physicians don’t screen for alcoholism,” he disulfiram, dates to the Prohibition era. ing full-scale testing. So Litten said the said. “When they do, they may note it, but Known commercially as Antabuse and agency isn’t putting all its eggs in one bas- don’t really do anything about it.” introduced in 1923, it makes people memo- ket. “You need as many weapons as pos- As far as the failure to prescribe exist- rably ill if they ingest alcohol, but it doesn’t sible to treat a complex disease like alcohol ing medications for AUD, Rotrosen blames stop the cravings. The other 2, naltrexone use disorder,” he said. a lack of knowledge. “A lot of doctors in and acamprosate, approved in 1994 and But therein lies a second difficulty. -

Effect of Combined Therapy with Thrombolysis and Citicoline in a Rat

Journal of the Neurological Sciences 247 (2006) 121–129 www.elsevier.com/locate/jns Effect of combined therapy with thrombolysis and citicoline in a rat model of embolic stroke ⁎ María Alonso de Leciñana a,e, , María Gutiérrez a,d, Jose María Roda a,c, Fernando Carceller a,c, Exuperio Díez-Tejedor a,b a Cerebrovascular Research Unit, La Paz University Hospital, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain b Department of Neurology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain c Department of Neurosurgery, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain d Cerebrovascular Experimental Lab, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain e Department of Neurology, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, Madrid, Spain Received 28 April 2005; received in revised form 3 January 2006; accepted 3 March 2006 Available online 22 June 2006 Abstract An approach combining reperfusion mediated by thrombolytics with pharmacological neuroprotection aimed at inhibiting the physiopathological disorders responsible for ischemia-reperfusion damage, could provide an optimal treatment of ischemic stroke. We investigate, in a rat embolic stroke model, the combination of rtPA with citicoline as compared to either alone as monotherapy, and whether the neuroprotector should be provided before or after thrombolysis to achieve a greater reduction of ischemic brain damage. One hundred and nine rats have been studied: four were sham-operated and the rest embolized in the right internal carotid artery with an autologous clot and divided among 5 groups: 1) control; 2) iv rtPA 5 mg/kg 30 min post-embolization 3) citicoline 250 mg/kg ip ×3 doses, 10 min, 24 h and 48 h post-embolization; 4) citicoline combined with rtPA following the same pattern; 5) rtPA combined with citicoline, with a first dose 10 min after thrombolysis. -

( 12 ) United States Patent

US010131766B2 (12 ) United States Patent (10 ) Patent No. : US 10 , 131, 766 B2 Hazen et al. (45 ) Date of Patent: Nov . 20 , 2018 ( 54 ) UNSATURATED POLYESTER RESIN 6 ,619 ,886 B1 9 /2003 Harrington 6 ,692 , 802 B1 2 / 2004 Nava SYSTEM FOR CURED IN - PLACE PIPING 7 , 135 ,087 B2 11/ 2006 Blackmore et al. 7 ,799 ,228 B2 9 /2010 Bomak et al . (71 ) Applicant : Interplastic Corporation , Saint Paul, 8 , 047, 238 B2 11/ 2011 Wiessner et al . MN (US ) 8 ,053 ,031 B2 11/ 2011 Stanley et al. 8 ,092 ,689 B2 1 / 2012 Gosselin (72 ) Inventors : Benjamin R . Hazen , Roseville , MN 8 , 298 , 360 B2 10 / 2012 Da Silveira et al. 8 ,418 , 728 B1 4 / 2013 Kiest , Jr . (US ) ; David J . Herzog , Maple Grove , 8 ,586 ,653 B2 11 / 2013 Klopsch et al. MN (US ) ; Louis R . Ross, Cincinnati , 8 ,636 , 869 B2 1 / 2014 Wiessner et al . OH (US ) ; Joel R . Weber , Moundsview , 8 ,741 , 988 B2 6 /2014 Klopsch et al. MN (US ) 8 , 877 , 837 B2 11/ 2014 Yu et al. 9 ,068 , 045 B2 6 /2015 Nava et al. 9 ,074 , 040 B2 7 / 2015 Turshani et al. ( 73 ) Assignee : Interplastic Corporation , St. Paul , MN 9 , 150 , 709 B2 10 / 2015 Klopsch et al . (US ) 9 , 207 , 155 B1 12 / 2015 Allouche et al. 9 ,273 ,815 B2 3 / 2016 Gillanders et al. ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 9 , 371, 950 B2 6 / 2016 Hairston et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 9 , 550 , 933 B2 1 /2017 Chatterji et al . -

Jp Xvii the Japanese Pharmacopoeia

JP XVII THE JAPANESE PHARMACOPOEIA SEVENTEENTH EDITION Official from April 1, 2016 English Version THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE Notice: This English Version of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia is published for the convenience of users unfamiliar with the Japanese language. When and if any discrepancy arises between the Japanese original and its English translation, the former is authentic. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 64 Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 41 of the Law on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law No. 145, 1960), the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministerial Notification No. 65, 2011), which has been established as follows*, shall be applied on April 1, 2016. However, in the case of drugs which are listed in the Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as ``previ- ous Pharmacopoeia'') [limited to those listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed in accordance with this notification (hereinafter referred to as ``new Pharmacopoeia'')] and have been approved as of April 1, 2016 as prescribed under Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the same law [including drugs the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare specifies (the Ministry of Health and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 104, 1994) as of March 31, 2016 as those exempted from marketing approval pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the Same Law (hereinafter referred to as ``drugs exempted from approval'')], the Name and Standards established in the previous Pharmacopoeia (limited to part of the Name and Standards for the drugs concerned) may be accepted to conform to the Name and Standards established in the new Pharmacopoeia before and on September 30, 2017. -

Impact of Citicoline Over Cognitive Impairments After General Anesthesia

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 Impact of Citicoline over Cognitive Impairments after General Anesthesia Kameliya Tsvetanova Department “Anesthesiology and Resuscitation“, Medical University – Pleven, Bulgaria Abstract: Postoperative cognitive delirium - POCD is chronic damage with deterioration of the memory, the attention and the speed of the processing of the information after anesthesia and operation. It is admitted that anesthetics and other perioperative factors are able to cause cognitive impairments through induction of apoptosis, neuro-inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and so on. More and more medicaments are used in modern medicine, as, for instance, Citicoline, which are in a position significantly to reduce this unpleasant complication of the anesthesia. Keywords: Postoperative cognitive delirium, anesthesia, Citicoline. 1. Introduction Therefore, Citocoline is the main intracellular precursor of phospholipid phosphatidyl choline. (13), (14), (15), (16), It is known that anesthetics and other perioperative factors (17), (18), (19), (20), (21), (22), (23), (24), (25), (26) are able to cause cognitive impairments through induction of apoptosis, neuro-inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction It exerts impact over the cholinergic system and acts as a and so on. choline donor for the enhanced synthesis of acetylcholine. Chronic damage with deterioration of the memory, the attention and the speed of the processing of the information -

Pharmacologcial Treatments for Methamphetamine Use Disorder

Abstract Background: Methamphetamine use disorder is a persistent and prevalent illness associated with serious physical, emotional, cognitive and social harms. No proven pharmacological treatments have yet been identified and psychological therapies are currently the only evidence based treatments. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found no quantitative evidence of benefit for psychostimulants in achieving abstinence or retention in treatment, but that review was limited to specific pharmacological agents (Bhatt et al, 2016). An older systematic review examined all treatments and found no single agent that demonstrated consistent efficacy (Brackins et al, 2011). Many additional studies have since been published. The aim of this systematic review is to critically evaluate the literature not previously covered by these and examine the evidence for efficacy of all possible pharmacological treatments. Methods: The literature search strategy consisted of an electronic search of PubMed. I included randomized controlled trials not previously reviewed of any pharmacological treatment for methamphetamine use disorder that reported methamphetamine use by urine drug screen as an outcome. I abstracted data from all identified studies using a standardized data collection instrument and critically analyzed the risk of bias, internal validity and external validity of all studies using a standardized form. I synthesized the review data. Results: I identified and analyzed 11 studies not previously reviewed. Pharmacological treatments used in these studies included buprenorphine, N-acetyl-cysteine, aripiprazole, citocoline, topiramate, naltrexone, mirtazapine, and a combined regimen of flumazenil/gabapentin/hydroxyzine. No study was found to have both good internal and good external validity. The overall level of internal validity within studies was severely limited by i small study size and high numbers of drop outs. -

Neuroprotective Effect of Citicoline on Retinal Cell Damage Induced by Kainic Acid in Rats

Neuroprotective Effect of Citicoline on Retinal Cell Damage Induced by Kainic Acid in Rats Yong Seop Han, MD, In Young Chung, MD, Jong Moon Park, MD, PhD, Ji Myeong Yu, MD, PhD Department of Ophthalmology, College of Medicine, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Korea Purpose: To examine whether citicoline has a neuroprotective effect on kainic acid (KA)-induced retinal damage. Methods: KA (6 nmol) was injected into the vitreous of rat eyes. Citicoline (500mg/kg, i.p.) was administered to the rats once before and twice a day after KA-injection for 3- and 7-day intervals. The neuroprotective effects of citicoline were estimated by measuring the thickness of the various retinal layers using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. In addition, immunohistochemistry was conducted to elucidate the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). Results: Morphometric analysis of retinal damage in KA-injected eyes showed significant cell loss in the inner nuclear layer (INL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL) of the retinas at 3 and 7 days after KA injection, but not in the outer nuclear layer (ONL). At 3 days after citicoline treatment, no significant changes were detected in the retinal thickness and immunoreactivities of eNOS and nNOS. The immunoreactivities of eNOS and nNOS increased in the retina at 7 days after the KA injection. However, prolonged treatment for 7 days significantly attenuated the immunoreactivities and the reduction of thickness. Conclusions: The results indicate that citicoline -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Cholinergic Regulation of Mood: from Basic and Clinical Studies to Emerging Therapeutics

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Mol Psychiatry Manuscript Author . Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2020 April 30. Published in final edited form as: Mol Psychiatry. 2019 May ; 24(5): 694–709. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0219-x. Cholinergic Regulation of Mood: From Basic and Clinical Studies to Emerging Therapeutics Stephanie C. Dulawa, Ph.D.1,*, David S. Janowsky, M.D.1 1Department of Psychiatry, University of California at San Diego Abstract Mood disorders are highly prevalent and are the leading cause of disability worldwide. The neurobiological mechanisms underlying depression remain poorly understood, although theories regarding dysfunction within various neurotransmitter systems have been postulated. Over 50 years ago, clinical studies suggested that increases in central acetylcholine could lead to depressed mood. Evidence has continued to accumulate suggesting that the cholinergic system plays a important role in mood regulation. In particular, the finding that the antimuscarinic agent, scopolamine, exerts fast-onset and sustained antidepressant effects in depressed humans has led to a renewal of interest in the cholinergic system as an important player in the neurochemistry of major depression and bipolar disorder. Here, we synthesize current knowledge regarding the modulation of mood by the central cholinergic system, drawing upon studies from human postmortem brain, neuroimaging, and drug challenge investigations, as well as animal model studies. First, we describe an illustrative series of early discoveries which suggest a role for acetylcholine in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Then, we discuss more recent studies conducted in humans and/or animals which have identified roles for both acetylcholinergic muscarinic and nicotinic receptors in different mood states, and as targets for novel therapies. -

Give Your Brain the Nutrients It Needs to Form Lasting

6/20/2019 Amazon.com: Alpha GPC Premium Choline - Pure Pharmaceutical Grade 600 mg Servings - Support Brain Focus and Memory - 300mg Capsules x60 -… Skip to main content All Try Prime brain supplement Deliver to EN Hello, Sign in 0 Guilford 06437 Today's Deals Your Amazon.com Gift Cards Account & Lists Orders Try Prime Cart ‹ Back to results Alpha GPC Premium Choline - Pure Pharmaceutical Grade 600 Price: $17.93 ($0.30 / Count) $18.87 $0.94 (5%) FREE Shipping mg Servings - Support Brain Focus and Memory - 300mg on orders over $25 shipped by Amazon or get Fast, Free Shipping with Amazon Prime 80 customer reviews | 3 answered questions In Stock. Sold by Emeritt and Fulfilled by Amazon. Subscribe & Save 5% 15% $17.93 ($0.30 / Count) Save 5% now and up to 15% on auto- deliveries. Learn more Get it Friday, Jun 21 One-time Purchase $18.87 ($0.31 / Count) 1+ Qty: Deliver every: 1 1 month ( Most common ) Subscribe now Add to List Share About the product GIVE YOURSELF A COMPETITIVE EDGE — Stack the odds in your favor to live the limitless life. You have a lot to achieve so let’s help you step up a gear with more productive days, increased drive, and stronger memory - and all that without relying on Adderall NO MORE BRAIN FOG — Feel more focused now. Unlock a boost in alertness, energy and power to help you deliver when it matters: get into flow, knock out that document, outlast Try Our Favorite Apple competitors, learn more efficiently, or crush that training session.