THE DIGGING STICK Volume 24, No 2 ISSN 1013-7521 August 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

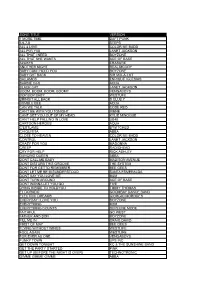

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON -

OM, Mcculloch, CS 340, CS 380, 966631401, 966631404

GB Operator’s manual 6-26 BG ÷úêîâîäñòâî çà SE Bruksanvisning 27-47 åêñïëîàòàöèß 277-304 DK Brugsanvisning 48-69 HU Használati utasítás 305-326 FI Käyttöohje 70-91 PL Instrukcja obs∏ugi 327-350 NO Bruksanvisning 92-112 EE Käsitsemisõpetus 351-371 FR Manuel d’utilisation 113-135 LV Lieto‰anas pamÇc¥ba 372-392 NL Gebruiksaanwijzing 136-158 LT Naudojimosi instrukcijos 393-413 IT Istruzioni per l’uso 159-181 SK Návod na obsluhu 414-434 DE Bedienungsanweisung 182-204 HR Priruãnik 435-455 ES Manual de instrucciones 205-227 SI Navodila za uporabo 456-476 CS 340 PT Instruções para o uso 228-250 CZ Návod k pouÏití 477-497 RU ÷óêîâîäñòâî ïî RO Instrucöiuni de utilizare 498-518 CS 380 ýêñïëóàòàöèè 251-276 GR √‰ËÁ›Â˜ ¯Ú‹Ûˆ˜ 519-542 TR Kullanım kılavuzu 543-563 1.$ 1 1 2 3 4 14 5 13 12 17 11 10 9 16 8 7 6 31 15 18 19 20 29 28 21 27 26 25 24 23 22 30 2 3 4 5 6 7 A A B 8 A 9 10 C min 4mm B (0,16’’) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 A B 20 21 22 A A 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 B 33 34 35 36 4 5 3 10 37 7 8 2 6 1 9 38 39 40 41 42 3 43 2 1 44 45 0,5 mm 46 Danger zone 47 Felling direction Retreat path 1 3 Danger zone 2 1 Danger zone 1 2 Retreat path 48 49 50 51 INTRODUCTION Dear Customer, Noise emission to the environment according to the European Thank you for choosing a McCulloch product. -

Things Come Different Lyrics (Album Version)

jilski – things come different lyrics (album version) (Parental Advisory – Explicit Lyrics) all lyrics written by J. Ilski 2016/17 Changes Changes – they come all at once. The fruits we reap belong to anyone. Changes – they come all the same. Embrace them now and never be the same again. Turnin' - I feel it all the way. Never worry that it wouldn't stay. Changes – they come all at once. The fruits we reap belong to anyone. Changes – they come all the same. Embrace them now and never be the same again. Until we fully come alive... The pains that we once felt – they will be left behind. Before we boldly cross the sea, Merely shadows you and me, You and me, you and me. Let me fly up to the stratosphere! I will call you when I'm there! But first, you have to let me, let me go! Let me go down to the place I fear! I will save you when I'm there! ('Cause - You know) Aspects of worry let me be their slave, Until we break out of their spectral cave. Until we fully come alive... The pains that we once felt – they will be left behind. Before we boldly cross the sea, Merely shadows you and me, You and me, you and me. Sleeping is where the goddess live(s). Never worry that it wouldn't stay. That it wouldn't stay-ay, Until we, Until we, Until we, Until we come alive, Come alive... (...) All songs found on the album: jilski – things come different www.jilski.com May 2017 Hey Joe Hey Joe, I said.. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

A Collection of Stories, Poetry and Advice for Those Bereaved by Suicide

Hope and Light in the Darkness A collection of stories, poetry and advice For those Bereaved by Suicide 56 1 Conclusion We hope you have found this booklet helpful. The stories and poetry shared have allowed us insight into the emotions a death by suicide can leave, and also the hope that clients can have for their future. We are able to make connections with each person as they express their deepest emotions and allow for healing within us. We would like to thank Evelyn Mc McCullough for her kind permis- sion to use her photographs in our booklet. These photographs al- low us to express some of the emotions through grief. Evelyn is go- ing through her own journey of Cancer treatment and finds photog- raphy a way of expressing her journey and it allows her to raise funds for cancer charities across Northern Ireland. For more information on her book please contact her via [email protected]. As each person grieves differently we at the bereavement by suicide service provide a unique service that supports each individual. We come together in a safe space to talk about our loved ones. This can be on a one to one or group basis. Through this journey of healing and acceptance we come to see the nature of their lives and not the nature of their deaths. If you are struggling with your grief please contact David or Danielle on 028 9441 3544. ‘No one ever really dies, as long as they took the time to leave us with fond memories.’ 2 55 Introduction This booklet ‘Hope and Light in the Darkness’ is a collection of stories, poetry and advice for families, friends and communities bereaved by suicide. -

A Description of Figurative Meaning Found in Michelle Branch’S the Spirit Room Album

A DESCRIPTION OF FIGURATIVE MEANING FOUND IN MICHELLE BRANCH’S THE SPIRIT ROOM ALBUM A PAPER WRITTEN BY NOVA SITUMEANG REG.NO. 172202009 ENGLISH DIPLOMA 3 STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2020 Universitas Sumatera Utara . Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I the undersigned NOVA SITUMEANG, hereby declare that I am the sole author of this paper. To the best of my knowledge this paper contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This paper contains no material which has been accepted as part of the requirements of any other academic degree or non-degree program, in English or in any other language. Signed : Date : August, 2020 i Universitas Sumatera Utara COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name : NOVA SITUMEANG Title of Paper : A DESCRIPTION OF FIGURATIVE MEANING FOUND IN MICHELLE BRANCH’S THE SPIRIT ROOM ALBUM Qualification : D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English language I hope that this paper should be available for reproduction at the direction the Librarian of English Diploma 3 Study Program, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara on the understanding that users made aware to their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. Signed : Date : August, 2020 ii Universitas Sumatera Utara ABSTRAK Judul dari kertas karya ini adalah “A Description of Figurative Meaning Found in Michelle Branch’s The Spirit Room Album”. Kertas Karya ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan majas yang ditemukan di dalam lagu-lagu milik Michelle Branch pada Album The Spirit Room. Teknik yang digunakan untuk mendeskripsikan data ini yaitu dengan membaca lirik lagu Michelle Branch yang diambil dari Albumnya yang berjudul The Spirit Room. -

Home Will Never Be the Same Again

Catching Health podcast: Home Will Never Be the Same Again. A conversation with co-authors Carol Hughes and Bruce Fredenburg Bruce: I had people come in who were suffering from either their bad divorce or their parents' bad divorce and among that group were adult children and they would say things like, I'm crushed. My family's gone. My family's dead and they're surprised that it's hitting them this hard and they think maybe there's something wrong with them. But if you think about it, it's going to be a major disruption in somebody's life when their family that they've known their entire life just disappears. And so over time we found that this was not just an underserved population, but actually an unserved population, and it's growing every year. Diane: Welcome to the Catching Health podcast. I'm Diane Atwood. I'm a health reporter and I share news and stories on my Catching Health blog and podcast that I hope will make a difference by educating enlightening, encouraging, and inspiring people to be as healthy as possible in mind, body and spirit. Today, I'm talking with Carol Hughes and Bruce Fredenburg. They are both licensed marriage and family therapists based in California and have many years of experience between them working with divorcing couples and families. They are also the coauthors of Home Will Never Be the Same Again: A Guide for Adult Children of Gray Divorce. So hello, Carol and Bruce. Welcome to Catching Health. I gave you a short version of your bios and so I give you permission to 1 add anything that you think is important and that you want people to know about you. -

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List Please note that this is a sample song list from one Karaoke & Jukebox Machine which may vary from the one you hire You can view a sample song list for digital jukebox (which comes with the karaoke machine) below. Song# ARTIST TRACK NAME 1 10CC IM NOT IN LOVE Karaoke 2 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY Karaoke 3 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE Karaoke 4 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP Karaoke 5 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Karaoke 6 A HA TAKE ON ME Karaoke 7 A HA THE SUN ALWAYS SHINES ON TV Karaoke 8 A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE Karaoke 9 AALIYAH I DONT WANNA Karaoke 10 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Karaoke 11 ABBA WATERLOO Karaoke 12 ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC Karaoke 13 ABBA SUPER TROUPER Karaoke 14 ABBA SOS Karaoke 15 ABBA ROCK ME Karaoke 16 ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY Karaoke 17 ABBA MAMMA MIA Karaoke 18 ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU Karaoke 19 ABBA FERNANDO Karaoke 20 ABBA CHIQUITITA Karaoke 21 ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO Karaoke 22 ABC POISON ARROW Karaoke 23 ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE Karaoke 24 ACDC STIFF UPPER LIP Karaoke 25 ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS Karaoke 26 ACE OF BASE DONT TURN AROUND Karaoke 27 ACE OF BASE THE SIGN Karaoke 28 ADAM ANT ANT MUSIC Karaoke 29 AEROSMITH CRAZY Karaoke 30 AEROSMITH I DONT WANT TO MISS A THING Karaoke 31 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR Karaoke 32 AFROMAN BECAUSE I GOT HIGH Karaoke 33 AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE Karaoke 34 ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW Karaoke 35 ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK U Karaoke 36 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALL I REALLY WANT Karaoke 37 ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC Karaoke 38 ALANNAH MYLES BLACK VELVET Karaoke -

Melanie C Featuring Lisa 'Left Eye' Lopes

Melanie C Never Be The Same Again mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop Album: Never Be The Same Again Country: New Zealand Released: 2000 Style: RnB/Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1699 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1764 mb WMA version RAR size: 1514 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 949 Other Formats: AHX MP3 DXD VOX DTS MP1 WAV Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Never Be The Same Again (Single Edit) 4:12 I Wonder What It Would Be Like A2 Mixed By – Patrick McCarthy*Producer – Rick RubinWritten-By – Billy Steinberg, Rick 3:38 Nowels Never Be The Same Again (Lisa Lopes Remix) Engineer – Neal H Pogue*Engineer [Assistant] – Vernon J Mungo*Executive Producer – A3 3:56 Left Eye, Max GousseRap [Lead Rap] – Lisa 'Left Eye' Lopes*Remix – Lisa Lopes*, Lorenzo Martin B1 Never Be The Same Again (Single Edit) 4:12 I Wonder What It Would Be Like B2 Mixed By – Patrick McCarthy*Producer – Billy Steinberg, Rick RubinWritten-By – Rick 3:38 Nowels Never Be The Same Again (Lisa Lopes Remix) Engineer – Neal H Pogue*Engineer [Assistant] – Vernon J Mungo*Executive Producer – B3 3:56 Left Eye, Max GousseRap [Lead Rap] – Lisa 'Left Eye' Lopes*Remix – Lisa Lopes*, Lorenzo Martin Notes ℗ & © 2000 Virgin Records Limited. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 24389 66324 2 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Melanie C Featuring Melanie C Lisa 'Left Eye' Lopes* VSCDT1762, Featuring Lisa Virgin, VSCDT1762, - Never Be The Same UK 2000 7243 8 96632 0 4 'Left Eye' Virgin 7243 8 96632 0 4 Again (CD, Single, Lopes* Enh) -

2021 Final Buzzer

CAMP BLUE RIDGE FINAL BUZZER 2021 ______________________________________________________ Dear Blue Ridge, THE MESS HALL!!!!! Remember when we ate in tents and in shifts early on in the summer? It worked and it was fun to be together and be back at camp, but the day we announced we could all go back into the Mess Hall was a game-changer!! It’s like a switch was flipped and everything went from black and white to living color!!! Because you all were in compliance and we all stayed healthy and safe, we got the green light to go indoors sooner than anticipated, lose the masks and all be together! As much as we all dreamed about this for such a long time, even for those who hadn’t experienced full camp dining and singing before, I’m not sure any of us could have anticipated the thrill and pure joy of this experience!! It was electric!! Why was this “first” such a big deal? That’s actually very easy to answer!! We are a family in the truest sense of the word. I think for many of us, having a meal with family is special. Our camp family feels it too and it’s a tradition that is honored every day, three times a day. Even though we see one another regularly, there’s a particular kind of excitement that occurs in the Mess Hall, where big and little sisters, “pretend” sisters, campers and staff all get to visit and share pieces of their day and hug and kiss as if it’s been weeks, not hours, since they saw each other last.