Java Sea Wreck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position Paper on ROC South China Sea Policy

Position Paper on ROC South China Sea Policy Republic of China (Taiwan) March 21, 2016 1. Preface The Nansha (Spratly) Islands, Shisha (Paracel) Islands, Chungsha (Macclesfield Bank) Islands, and Tungsha (Pratas) Islands (together known as the South China Sea Islands) were first discovered, named, and used by the ancient Chinese, and incorporated into national territory and administered by imperial Chinese governments. Whether from the perspective of history, geography, or international law, the South China Sea Islands and their surrounding waters are an inherent part of ROC territory and waters. The ROC enjoys all rights over them in accordance with international law. This is indisputable. Any claim to sovereignty over, or occupation of, these areas by other countries is illegal, irrespective of the reasons put forward or methods used, and the ROC government recognizes no such claim or occupation. With respect to international disputes regarding the South China Sea, the ROC has consistently maintained the principles of safeguarding sovereignty, shelving disputes, pursuing peace and reciprocity, and promoting joint development, and in accordance with the United Nations Charter and international law, called for consultations with other countries, participation in related dialogue and cooperative mechanisms, and peaceful 1 resolution of disputes, to jointly ensure regional peace. 2. Grounds for the ROC position History The early Chinese have been active in the South China Sea since ancient times. Historical texts and local gazetteers contain numerous references to the geographical position, geology, natural resources of the South China Sea waters and landforms, as well as the activities of the ancient Chinese in the region. The South China Sea Islands were discovered, named, used over the long term, and incorporated into national territory by the early Chinese, so even though most of the islands and reefs are uninhabited, they are not terra nullius. -

Southeast Asian Studies

SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Vol. 2, No. 3 December 2013 CONTENTS Special Focus Reconstructing Intra-Southeast Asian Trade, c.1780–1870: Evidence of Regional Integration under the Regime of Colonial Free Trade Guest Editor: Kaoru SUGIHARA Kaoru SUGIHARA Introduction ............................................................................................(437) Tomotaka KAWAMURA Atsushi KOBAYASHI The Role of Singapore in the Growth of Intra-Southeast Asian Trade, c.1820s–1852 .....................................................................................(443) Ryuto SHIMADA The Long-term Pattern of Maritime Trade in Java from the Late Eighteenth Century to the Mid-Nineteenth Century .......................................................(475) Atsushi OTAA Tropical Products Out, British Cotton In: Trade in the Dutch Outer Islands Ports, 1846–69 ..........................(499) Articles Thanyathip Sripana Tracing Hồ Chí Minh’s Sojourn in Siam ..............................................(527) Sawitree Wisetchat Visualizing the Evolution of the Sukhothai Buddha ............................(559) Research Report Bounthanh KEOBOUALAPHA Farmers’ Perceptions of Imperata cylindrica Infestation Suchint SIMARAKS in a Slash-and-Burn Cultivation Area of Northern Lao PDR ..........(583) Attachai JINTRAWET Thaworn ONPRAPHAI Anan POLTHANEE Book Reviews Robert H. TAYLORR Yoshihiro Nakanishi. Strong Soldiers, Failed Revolution: The State and Military in Burma, 1962–88. Singapore and Kyoto: NUS Press in association with Kyoto University Press, 2013, xxi+358p. -

An Optimization Model for Port Service Network of Refrigerated Containers Based on Transportation Time Reliability

International Journal of Engineering and Technology, Vol. 9, No. 5, October 2017 An Optimization Model for Port Service Network of Refrigerated Containers Based on Transportation Time Reliability Xiangqun Song, Qianli Ma, Wenyuan Wang, and Shibo Li Abstract—In order to develop the transshipment and temperature, when the temperature get control, time processing capacity of port nodes in the container port service reliability can be decisive to evaluate the efficiency of cold network and meet the increasing demand for cold chain chain logistics. Domestic and foreign researchers have logistics transportation, container flow quantity should be conducted a lot of research in the past which can be reasonably distributed in port nodes which undertake primarily divided into two aspects. The first aspect is the functions of transportation and transfer in the cold chain. evaluation and calculation method of time reliability. For Through the study of refrigerated container service network, this paper establishes an optimization model for port service example, Chang J. S. [7] defined time reliability as the network of refrigerated container with minimizing the total difference between actual arrival time and schedule time, cost as the objective, transportation time reliability and storage Liang C. Y. [8] established the time reliability calculation capacity of the refrigerated container in port nodes as model from two aspects of the running time and the waiting constraints to achieve the optimal container flow allocation in time, and Namazi-Rad M. R. [9] introduced time window to transshipment ports under different supply and demand evaluate the reliability, Jong G. D. [10] took the method of quantity. preference survey to assess the transportation time reliability. -

China's Historical Claim in the South China Sea

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-13 "Since Time Immemorial": China's Historical Claim in the South China Sea Chung, Chris Pak Cheong Chung, C. P. (2013). "Since Time Immemorial": China's Historical Claim in the South China Sea (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27791 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/955 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “Since Time Immemorial”: China’s Historical Claim in the South China Sea by Chris P.C. Chung A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2013 © Chris Chung 2013 Abstract Four archipelagos in the South China Sea are territorially disputed: the Paracel, Spratly, and Pratas Islands, and Macclesfield Bank. The People’s Republic of China and Republic of China’s claims are embodied by a nine-dashed U-shaped boundary line originally drawn in an official Chinese map in 1948, which encompasses most of the South China Sea. Neither side has clarified what the line represents. Using ancient Chinese maps and texts, archival documents, relevant treaties, declarations, and laws, this thesis will conclude that it is best characterized as an islands attribution line, which centres the claim simply on the islands and features themselves. -

CAT CRAZY, TRI FI and Other Multihull Comparisons by Jim Brown

CAT CRAZY, TRI FI And Other Multihull Comparisons By Jim Brown “There is nothing, absolutely nothing, quite so much worth doing as simply messing about in…” Multihulls! That paraphrased quote is pilfered for the most part from Ratty, the revered rodent in Kenneth Grahame’s venerated tale “The Wind in the Willows.” Of course, Grahame and Ratty said it of ordinary boats, and neither would have, even could have, said it of multihulls. But if Brown had been the author instead of Grahame, his character Ratty might have said something like, “There is nothing, absolutely nothing quite so creative as screwing around with multihulls.” By “screwing around,” Ratty would have spoken literally, meaning to conceive, gestate, whelp, wean and release upon the Earth’s fluid interface one’s very own flesh and blood multihulls. And that’, impatient reader, is what this appendix is about, so like most appendices reading it is strictly optional. In that you are reading on, please be prepared for some sacrilege. Suggesting there is something divine about boat design and construction I will try to trace multihull origins by expanding on the theorem expressed by my late friend Walt Glaser who said (in Chapter 1 of my memoir, “Among the Multihulls,”), “A man builds a boat to make up for the fact that he can’t build a baby… What else can a guy produce with his own body that so closely simulates a living thing?” It took me many years of both messing about in and screwing around with boats to apprehend this aspect of watercraft, and I admit that it still takes quite a stretch for me to accept the notion. -

Fitting the Unstayed Mast Rig To

ITTING THE UNSTAYED MAST RIG TO YOUR BOAT SOME POPULAR QUESTIONS ANSWERED: - . Will it suit any boat of any hull shape? - Yes, and will particularly aid shallow draft hulls of low ballast ratio as the flexibility of the mast reduces heeling in all conditions. 2. Can it be fitted to multihulls? - Yes, Trimaran installations are similar to monohulls. Catamarans can either have modified bridge decks to obtain sufficient bury of mast or fit a smaller mast in each hull. 3. Can I use my existing stayed rig mast?- No, with the exception of some solid timber Gaff rig masts. 4. Does the mast have to be keel stepped? - Preferably, but it can be fitted in a deck tabernacle. 5. Where is the mast stepped? - Approximately 2 to 4 feet forward of a stayed mast postion. 6. Does it have to be near a bulkhead? - No, as the load transmitted to the deck is not enormous. 7. What structural modifications will I have to make to my boat? - Probably increase the deck strength at the mast by adding:- - for GRP boats more layup of C.S. matt which will be hidden by the head lining under the deck. - for steel, alloy, ferrocement, timber boats, add a deck beam. The mast step only needs to be firmly secured to the keel and no extra reinforcement is necessary to be the boat's keel. - for sheeting to the pushpit, possibly, add a bracing strut across the existing tube, such as a sheet track. 8. How many sails and of what area should be used? - As a general rule:- For boats up to 30 ft., one sail is more ideal. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Bangsa Indonesia Sejak

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Bangsa Indonesia sejak dahulu sudah dikenal sebagai bangsa pelaut yang menguasai jalur-jalur perdagangan. Sebagai bangsa pelaut maka pengetahuan kita akan teknologi perkapalan Nusantara pun seharusnya kita ketahui. Catatan-catatan sejarah serta bukti-bukti tentang teknologi perkapalan Nusantara pada masa klasik memang sangatlah minim. Perkapalan Nusantara pada masa klasik, khususnya pada masa kerajaan Hindu-Buddha tidak meninggalkan bukti lukisan-lukisan bentuk kapalnya, berbeda dengan bangsa Eropa seperti Yunani dan Romawi yang bentuk kapal-kapal mereka banyak terdapat didalam lukisan yang menghiasi benda porselen. Penemuan bangkai-bangkai kapal yang berasal dari abad ini pun tidak bisa menggambarkan lebih lanjut bagaimana bentuk aslinya dikarenakan tidak ditemukan secara utuh, hanya sisa-sisanya saja. Sejak kedatangan bangsa Eropa ke Nusantara pada abad ke 16, bukti-bukti mengenai perkapalan yang dibuat dan digunakan di Nusantara mulai terbuka. Catatan-catatan para pelaut Eropa mengenai pertemuan mereka dengan kapal- kapal Nusantara, serta berbagai lukisan-lukisan kota-kota pelabuhan di Nusantara yang juga dibuat oleh orang-orang Eropa. Sejak abad ke-17, di Eropa berkembang seni lukis naturalistis, yang coba mereproduksi keadaan sesuatu obyek dengan senyata mungkin; gambar dan lukisan yang dihasilkannya membahas juga pemandangan-pemandangan kota, benteng, pelabuhan, bahkan pemandangan alam 2 di Asia, di mana di sana-sini terdapat pula gambar perahu-perahu Nusantara.1 Catatan-catatan Eropa ini pun memuat nama-nama dari kapal-kapal Nusantara ini, yang ternyata sebagian masih ada hingga sekarang. Dengan menggunakan cacatan-catatan serta lukisan-lukisan bangsa Eropa, dan membandingkan bentuk kapalnya dengan bukti-bukti kapal yang masih digunakan hingga sekarang, maka kita pun bisa memunculkan kembali bentuk- bentuk kapal Nusantara yang digunakan pada abad-abad 16 hingga 18. -

The Discovery of the Sea

The Discovery of the Sea "This On© YSYY-60U-YR3N The Discovery ofthe Sea J. H. PARRY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London Copyrighted material University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Copyright 1974, 1981 by J. H. Parry All rights reserved First California Edition 1981 Published by arrangement with The Dial Press ISBN 0-520-04236-0 cloth 0-520-04237-9 paper Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 81-51174 Printed in the United States of America 123456789 Copytightad material ^gSS3S38SSSSSSSSSS8SSgS8SSSSSS8SSSSSS©SSSSSSSSSSSSS8SSg CONTENTS PREFACE ix INTROn ilCTION : ONE S F A xi PART J: PRE PARATION I A RELIABLE SHIP 3 U FIND TNG THE WAY AT SEA 24 III THE OCEANS OF THE WORI.n TN ROOKS 42 ]Jl THE TIES OF TRADE 63 V THE STREET CORNER OF EUROPE 80 VI WEST AFRICA AND THE ISI ANDS 95 VII THE WAY TO INDIA 1 17 PART JJ: ACHJF.VKMKNT VIII TECHNICAL PROBL EMS AND SOMITTONS 1 39 IX THE INDIAN OCEAN C R O S S T N C. 164 X THE ATLANTIC C R O S S T N C 1 84 XJ A NEW WORT D? 20C) XII THE PACIFIC CROSSING AND THE WORI.n ENCOMPASSED 234 EPILOC.IJE 261 BIBLIOGRAPHIC AI. NOTE 26.^ INDEX 269 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1 An Arab bagMa from Oman, from a model in the Science Museum. 9 s World map, engraved, from Ptolemy, Geographic, Rome, 1478. 61 3 World map, woodcut, by Henricus Martellus, c. 1490, from Imularium^ in the British Museum. -

An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo: a Vessel from the Junk Trade

An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo: A Vessel from the Junk Trade Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies A Journal of the Southeast Asian Studies Student Association Vol 1, No. 2 Fall 1997 Contents Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Article 4 Article 5 Article 6 Article 7 Article 8 An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo A Vessel from the Junk Trade Hans Van Tilburg Hans Van Tilberg is a Ph.D. candidate in History and instructor of the maritime archaeology field school at the University of Hawai'i, Manoa. His research interests have focused on maritime history and underwater archaeology in Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Notes The topic of Chinese shipping to and from Southeast Asia has fascinated me for quite a while now. One of the reasons I find it so interesting is that it's such a difficult subject to research. One of the main problems seems to be that many aspects of the private commercial sea-going trade simply went unrecorded. Often only the barest information of "size of ship" and "number of crew" was ever committed to register, while the efforts of ship construction, fitting out, manning, and the details of the actual voyages, remained known only at the village or family level. And as has been noted by many observers, officially the Chinese government had very little interest in the activities of those Chinese who went abroad, those who were foolish enough to want to travel so many miles away from home. Yet the influence of what is commonly known as the Junk Trade, especially in the eighteeth and nineteenth centuries, is no small subject. -

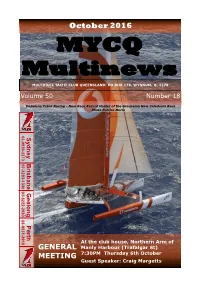

October 2016

October 2016 MULTIHULL YACHT CLUB QUEENSLAND: PO BOX 178, WYNNUM. Q. 4178 Volume 50 Number 18 Vodafone Frank Racing - New Race Record Holder of the Groupama New Caledonia Race Photo Patrice Morin 02 Sydney Brisbane Geelong Perth Geelong Brisbane Sydney - 9939 - 2273 07 2273 - 3203 - 1330 03 - 5222 - 2930 082930 - 9331 - 3910 3910 At the club house, Northern Arm of GENERAL Manly Harbour (Trafalgar St) MEETING 7:30PM Thursday 6th October Guest Speaker: Craig Margetts 2 Monthly Events 8-9th October St Helena Cup 15-16th October Spring Series Passage Series Combined Clubs Races 13 & 14 23rd October Triangles 29th-30th October Mooloolaba Weekend Commodore’s Comment By Bruce Wieland SPRING SERIES The new MYCQ Spring Series kicks off this coming weekend. The first leg is the St Helena Cup, followed by two very innovative courses the following weekend featuring optional simultaneous starts at either north or south of the river. The northern and southern courses overlap so both fleets will cross paths several times. The concept of these courses is the brainchild of Past Commodore Richard Jenkins and promises to be a lot of fun. The final weekend of the Spring Series will include the MCC triangles on Sunday the 23rd October. For the cruisers, THERE ARE SHORTENED COURSES, so find a crew and come sailing with the race fleet! OMR VIDEO The edited video of the OMR Review Committee information meeting is finally completed and is now available on the MYCQ website. Thanks to Sean for capturing the essence of the meeting, but a big thanks also to the OMR Committee members Alasdair Noble, Mike Hodges and Geoff Cruse for their easily understood presentation detailing the amendments to the OMR Rule. -

Remarks on the Terminology of Boatbuilding and Seamenship in Some Languages of Southern Sulawesi

This article was downloaded by:[University of Leiden] On: 6 January 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 769788091] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Indonesia and the Malay World Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713426698 Remarks on the terminology of boatbuilding and seamanship in some languages of Southern Sulawesi Horst Liebner Online Publication Date: 01 November 1992 To cite this Article: Liebner, Horst (1992) 'Remarks on the terminology of boatbuilding and seamanship in some languages of Southern Sulawesi', Indonesia and the Malay World, 21:59, 18 - 44 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/03062849208729790 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03062849208729790 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Adversarial Dynamic Shapelet Networks

The Thirty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-20) Adversarial Dynamic Shapelet Networks Qianli Ma,1 Wanqing Zhuang,1 Sen Li,1 Desen Huang,1 Garrison W. Cottrell2 1School of Computer Science and Engineering, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China 2Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract from different categories are often distinguished by their local pattern rather than by global structure, shapelets are Shapelets are discriminative subsequences for time series an effective approach to this problem. Moreover, shapelet- classification. Recently, learning time-series shapelets (LTS) was proposed to learn shapelets by gradient descent directly. based methods can provide interpretable decisions (Ye and Although learning-based shapelet methods achieve better re- Keogh 2009) since the important local patterns found from sults than previous methods, they still have two shortcomings. original subsequences are used to identify the category of First, the learned shapelets are fixed after training and cannot time series. adapt to time series with deformations at the testing phase. The original shapelet-based algorithm constructs a deci- Second, the shapelets learned by back-propagation may not sion tree classifier by recursively searching the best shapelet be similar to any real subsequences, which is contrary to the original intention of shapelets and reduces model inter- data split (Ye and Keogh 2009). The candidate subsequences pretability. In this paper, we propose a novel shapelet learning are assessed by information gain, and the best shapelet is model called Adversarial Dynamic Shapelet Networks (AD- found at each node of the tree through enumerating all candi- SNs).