2Nd Edition (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organisation Name Primary Sporting Activity Antrim and Newtownabbey

Primary Sporting Organisation Name Activity Antrim And Newtownabbey Borough Council 22nd Old Boys FC Association Football 4th Newtownabbey Football Club Association Football Antrim Amateur Boxing Club Boxing Antrim Jets American Football Club American Football Antrim Rovers Association Football Ballyclare Colts Football Club Association Football Ballyclare Comrades Football Club Association Football Ballyclare Golf Club Golf Ballyclare Ladies Hockey Club Hockey Ballyearl Squash Rackets & Social Club Squash Ballynure Old Boys FC Association Football Belfast Athletic Football Club Association Football Belfast Star Basketball Club Basketball Burnside Ulster-Scots Society Association Football Cargin Camogie Club Camogie Chimney Corner Football Club Association Football Cliftonville Academy Cricket Club Cricket Crumlin United FC Association Football Crumlin United Mini Soccer Association Football East Antrim Harriers AC Athletics Elite Gym Academy CIC Gymnastics Erins Own Gaelic Football Club Cargin Gaelic Sports Evolution Boxing Club Boxing Fitmoms & Kids Multisport Glengormley Amateur Boxing Club Boxing Golift Weightlifting Club Weightlifting Mallusk Harriers Athletics Massereene Golf Club Golf Monkstown Amateur Boxing Club Boxing Mossley Ladies Hockey Club Hockey Muckamore Cricket and Lawn Tennis Club Multisport Naomh Eanna CLG Gaelic Sports Northern Telecom Football Club (Nortel FC) Association Football Old Bleach Bowling Club Bowling Ophir RFC Rugby Union Owls Ladies Hockey Club Hockey Parasport NI Athletics Club Disability Sport Parkview -

People and Communities Committee

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES COMMITTEE Subject: GAA Strategy for Belfast Date: 10 April 2018 Reporting Officer: Nigel Grimshaw, Director City & Neighbourhood Services Department Rose Crozier, Assistant Director City & Neighbourhood Services Contact Officer: Department Restricted Reports Is this report restricted? Yes No X If Yes, when will the report become unrestricted? After Committee Decision After Council Decision Some time in the future Never Call-in Is the decision eligible for Call-in? Yes X No 1.0 Purpose of Report or Summary of main Issues 1.1 Ulster Branch Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) and County Antrim Board have developed a strategy for Belfast following extensive consultation across their members and other stakeholders. A five year action plan for development of the sport in Belfast has been developed and costed at approximately £319,000 per annum, this model is based on funding from four key stakeholders and GAA have asked Belfast City Council to be a supporting partner in delivery of the action plan. 2.0 Recommendations 2.1 That Committee is asked to give approval in principle to; 1. permit officers to work with GAA to deliver and fund the Belfast Action Plan through the Belfast Community Benefits Initiative partnership agreement 2. develop appropriate arrangements for management of GAA bookings to streamline processes and improve sporting outcomes 3.0 Main report Key Issues 3.1 GAA has a good record of working in partnership with Council, having invested significantly in development of a range of sites with the installation of 3G pitches to improve accessibility to training and competition opportunities within the City. -

The Irish Soccer Split: a Reflection of the Politics of Ireland? Cormac

1 The Irish Soccer Split: A Reflection of the Politics of Ireland? Cormac Moore, BCOMM., MA Thesis for the Degree of Ph.D. De Montfort University Leicester July 2020 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements P. 4 County Map of Ireland Outlining Irish Football Association (IFA) Divisional Associations P. 5 Glossary of Abbreviations P. 6 Abstract P. 8 Introduction P. 10 Chapter One – The Partition of Ireland (1885-1925) P. 25 Chapter Two – The Growth of Soccer in Ireland (1875-1912) P. 53 Chapter Three – Ireland in Conflict (1912-1921) P. 83 Chapter Four – The Split and its Aftermath (1921-32) P. 111 Chapter Five – The Effects of Partition on Other Sports (1920-30) P. 149 Chapter Six – The Effects of Partition on Society (1920-25) P. 170 Chapter Seven – International Sporting Divisions (1918-2020) P. 191 Conclusion P. 208 Endnotes P. 216 Sources and Bibliography P. 246 3 Appendices P. 277 4 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my two supervisors Professor Martin Polley and Professor Mike Cronin. Both were of huge assistance throughout the whole process. Martin was of great help in advising on international sporting splits, and inputting on the focus, outputs, structure and style of the thesis. Mike’s vast knowledge of Irish history and sporting history, and his ability to see history through many different perspectives were instrumental in shaping the thesis as far more than a sports history one. It was through conversations with Mike that the concept of looking at partition from many different viewpoints arose. I would like to thank Professor Oliver Rafferty SJ from Boston College for sharing his research on the Catholic Church, Dr Dónal McAnallen for sharing his research on the GAA and Dr Tom Hunt for sharing his research on athletics and cycling. -

Across an Open Field Stories and Artwork by Children from Ireland and Northern Ireland About the Decade of Commemorations 1912 – 1922

Across an Open Field Stories and artwork by children from Ireland and Northern Ireland about the Decade of Commemorations 1912 – 1922 Contents Across an Open Field: Stories and artwork about the Decade of Commemorations, 1912 - 1922 by children from Ireland and Northern Ireland © Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership Ltd. 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without prior written authorisation. 9 1912: Shipyards and Unions ISBN 978-19024330732 Published by: 15 1913: The Lockout Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership Ltd. Carrigeens, Ballinful, Co. Sligo, Ireland. 23 Social History (+353)719124945 http://kidsown.ie 39 1914 – 1918: World War 1 http://www.100yearhistory.com Charity number: 20639 55 1916: The Easter Rising Kids’ Own Editorial team: Orla Kenny, Jo Holmwood, Emma Kavanagh 67 International Stories Design: 75 1919 – 1921: The War of Independence Martin Corr 85 1921: Partition and Civil War Text & images: All text and images by participating children 88 1922: The Anglo-Irish Treaty Project writer: 89 1912 – 1922: Suffragettes Mary Branley 96 List of participating schools and children Project artist: Ann Donnelly 99 Our reflections on this work Acknowledgements: Kids’ Own would like to thank the following for their support and involvement in the 100 Year History Project: Fionnuala Callanan, Director, and Liguori Cooney of the Reconciliation Fund (Department of Foreign Affairs); Paul Fields, Director, Kilkenny Education Centre and Marie O’Donoghue, Education Authority, Northern Ireland; Carmel O’Doherty, Director of Limerick Education Centre; Bernard Kirk, Director of Galway Education Centre; Jimmy McGough, Director of Monaghan Education Centre; Pat Seaver, Director of Blackrock Education Centre; and Gerard McHugh, Director of Dublin West Education Centre. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for People and Communities Committee, 12/04/2018 16:30

Democratic Services Section Chief Executive’s Department Belfast City Council City Hall Belfast BT1 5GS 5th April, 2018 MEETING OF PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES COMMITTEE Dear Alderman/Councillor, The above-named Committee will meet in the Lavery Room - City Hall on Thursday, 12th April, 2018 at 4.30 pm, for the transaction of the business noted below. You are requested to attend. Yours faithfully, SUZANNE WYLIE Chief Executive AGENDA: 1. Routine Matters (a) Apologies (b) Minutes (c) Declarations of Interest 2. Matters referred back from Council/Motions (a) Motion - Childcare Strategy (Withdrawn) (Pages 1 - 2) (b) Motion - Greenway Strategy (Pages 3 - 4) 3. Restricted Items (a) Proposed Country Musical event in lower field, Botanic Gardens (Pages 5 - 6) (b) Temporary structures at Alderman Tommy Patton Memorial Park (Pages 7 - 14) - 2 - 4. Committee/Strategic Issues (a) People and Communities Plan Committee Plan 2018/19 (Pages 15 - 18) (b) Housing Provision in Belfast (Pages 19 - 22) (c) GAA Strategy for Belfast City Council (Pages 23 - 26) (d) Minutes of Strategic Cemetaries and Crematorium Development Working Group (Pages 27 - 32) 5. Physical Programme and Asset Management (a) Playground Improvement Programme 2018/19 (Pages 33 - 48) (b) Partner Agreements and Facilities Management Agreements Update and Review (Pages 49 - 54) (c) Alleygating - Notice of Traffic Regulation Order 2018 (Pages 55 - 68) (d) Proposed relocation of Moyard Playground (Pages 69 - 72) (e) Belfast Flare Pavilion Manderson Street (Pages 73 - 74) 6. Operational Issues (a) -

Community Relations Funding Through Local Councils in Northern Ireland

Research and Information Service Briefing Paper Paper 18/15 28 November 2014 NIAR 716-14 Michael Potter and Anne Campbell Community Relations Funding through Local Councils in Northern Ireland 1 Introduction This paper briefly outlines community relations1 funding for groups through local councils in Northern Ireland in the context of the inquiry by the Committee for the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister into the Together: Building a United Community strategy2. The paper is a supplement to a previous paper, Community Relations Funding in Northern Ireland3. It is not intended to detail all community relations activities of local councils, but a summary is given of how funding originating in the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minster (OFMdFM) is used for grants to local organisations. 1 It is not within the scope of this paper to discuss terminology in relation to this area. The term ‘community relations’ has tended to be replaced by ‘good relations’ in many areas, although both terms are still in use in various contexts. ‘Community relations’ is used here for simplicity and does not infer preference. 2 ‘Inquiry into Building a United Community’, Committee for OFMdFM web pages, accessed 2 October 2014: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Assembly-Business/Committees/Office-of-the-First-Minister-and-deputy-First- Minister/Inquiries/Building-a-United-Community/. 3 Research and Information Service Briefing Paper 99/14 Community Relations Funding in Northern Ireland, 9 October 2014: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/RaISe/Publications/2014/ofmdfm/9914.pdf. Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly 1 NIAR 716-014 Briefing Paper 2 Community Relations Funding in Local Councils Funding from OFMdFM is distributed to each of the councils at a rate of 75%, with the remaining 25% matched by the council itself. -

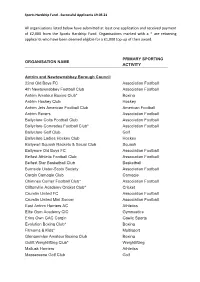

Organisations Listed Below Have Submitted at Least One Application and Received Payment of £2,000 from the Sports Hardship Fund

Sports Hardship Fund - Successful Applicants 19.03.21 All organisations listed below have submitted at least one application and received payment of £2,000 from the Sports Hardship Fund. Organisations marked with a * are returning applicants who have been deemed eligible for a £1,000 top-up of their award. PRIMARY SPORTING ORGANISATION NAME ACTIVITY Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council 22nd Old Boys FC Association Football 4th Newtownabbey Football Club Association Football Antrim Amateur Boxing Club* Boxing Antrim Hockey Club Hockey Antrim Jets American Football Club American Football Antrim Rovers Association Football Ballyclare Colts Football Club Association Football Ballyclare Comrades Football Club* Association Football Ballyclare Golf Club Golf Ballyclare Ladies Hockey Club Hockey Ballyearl Squash Rackets & Social Club Squash Ballynure Old Boys FC Association Football Belfast Athletic Football Club Association Football Belfast Star Basketball Club Basketball Burnside Ulster-Scots Society Association Football Cargin Camogie Club Camogie Chimney Corner Football Club* Association Football Cliftonville Academy Cricket Club* Cricket Crumlin United FC Association Football Crumlin United Mini Soccer Association Football East Antrim Harriers AC Athletics Elite Gym Academy CIC Gymnastics Erins Own GAC Cargin Gaelic Sports Evolution Boxing Club* Boxing Fitmoms & Kids* Multisport Glengormley Amateur Boxing Club Boxing Golift Weightlifting Club* Weightlifting Mallusk Harriers Athletics Massereene Golf Club Golf Sports Hardship Fund - Successful -

Sport Northern Ireland Corporate Plan 2012-15

Sport Northern Ireland Corporate Plan 2012-15 The leading public body for the development of sport in Northern Ireland 2 Sport Northern Ireland Annual Review 2008 Contents 4 Foreword 6 Introducing Sport Northern Ireland 8 The Value of Sport and Physical Recreation 10 Values and Investment Principles 12 Strategic Drivers for Sport 14 Understanding Our Priorities 16 Building On Progress 18 Looking Ahead 20 Achieving Our Priorities 24 Approach to Delivery 26 Resourcing Our Priorities 28 Measuring Our Progress 30 Impact of Our Work 32 Appendix 1: LISPA Framework 33 Appendix 2: World Leading System for Athlete Development 34 Appendix 3: Sport Matters Targets Corporate Plan 2012-15 Plan Corporate Sport Northern Ireland Northern Sport 3 Foreword Sport Northern Ireland Corporate Plan 2012-15 Eamonn McCartan Sport and physical recreation make a unique costs the UK economy £3bn per annum. Across contribution to society. It is valued by many the UK, we spend £886 per person per year on Chief Executive thousands of individuals who are participants, the National Health Service; contrast this with Sport Northern Ireland parents, teachers, coaches, officials, volunteers, the £1 per person per year spent on sport. I administrators and spectators. It provides a believe that by increasing funding to sport, as strong platform in which to develop strong, the Scottish Executive has done, Sport Northern cohesive and inclusive communities. In addition Ireland could actively help prevent a lot of that ill to sport’s intrinsic value, it also offers a number health. of extrinsic benefits which contribute wider But beyond the broader value, sport and physical government objectives, such as, growing the recreation continues to provide us with those economy, improving education and skills, and inspirational, incomparable and invaluable promoting social inclusion. -

BUCS Sport Review

TOUCH RUGBY SPORT REVIEW PROPOSAL PREPARED BY JACK HARRIS (ETA) | 5 JULY 2021 CYCLE THREE Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Our Vision for Touch in Universities 4 Touch Rugby: An Overview 5 The University National Touch Series (Uni NTS) 5 Operations and Funding 6 Athlete Data 6 The Uni NTS in Pictures 7 Purpose 9 Student Athlete Types 9 The Benefits 9 Strategic Alignment 10 Inter University Sport 10 Performance Sport 10 Social & Recreational Sport 10 Professional & Workforce Development 11 Equality, Diversity & Inclusion 11 University Admissions & Offer of Touch 12 Consultation & Support 13 Scale 13 Member Engagement 13 Future Growth 13 Working across the UK 13 Resource Implications 14 BUCS Resource Implications 14 Institute and Athlete Resource Implications 14 Wider Impact Assessment 15 Pathways & Competitions 15 BUCS Sport Review - Cycle Three - Touch Rugby 1 “The Rugby Family” 15 BUCS Compliance & Governance 15 Match Officials 15 Sustainability & Funding 16 Diversity & Inclusion 16 Key Performance Indicators 17 First Year Targets 17 Medium Term (3 Year) Targets 17 Conclusion 17 Appendices 17 The England Touch Association 18 Federation of International Touch 19 Touch Club Data 20 Student Athlete Surveying 21 BUCS Sport Review - Cycle Three - Touch Rugby 2 Executive Summary Touch Rugby, known as “Touch”, is already extensively played in and between Universities across England, Scotland and Wales, with plans for growth in Northern Ireland. As the governing body for the sport in England, the England Touch Association (ETA) has identified universities as one of the core areas of growth in our 10 year vision. We believe that by adopting Touch into the BUCS student program, we can provide an inclusive sport for students of all backgrounds and abilities. -

SPORTS BROCHURE WELCOME at Crowne Plaza Belfast We’Re at the Heart of SportNg Excellence in the City

BELFAST Crowne Plaza Belfast – Your Winning Accommodation Provider in Belfast. SPORTS BROCHURE www.cpbelfast.com WELCOME At Crowne Plaza Belfast we’re at the heart of sporting excellence in the city. With onsite and surrounding sports facilities, we will ensure your team gets the best possible service when you stay with us. Whether you are competing in a tournament or match in Belfast, on tour or simply visiting for training purposes, our dedicated staff will take care of your requirements, ensuring your team can focus on achieving what’s really important. OUR SPORTING PARTNERS We are proud to work closely with a host of sporting partners across a range of sports in Belfast. We have also had the privilege of hosting a number of sports teams from junior to International level including IRFU, IFA (Under 19s and Under 21s), Newport Gwent Dragons, UCD Swim Team, Athletics NI, Special Olympics, Belfast Giants and Connacht and Leinster Junior Teams. OUR FACILITIES Our recently refurbished Crowne Plaza Belfast boasts a welcoming and contemporary art deco-inspired lobby and stunning meeting and event spaces. The hotel features 120 luxurious bedrooms including twin and king double rooms, wheelchair accessible rooms, interconnecting rooms and suites – the perfect mix to accommodate any sports team. Our Great Oak Conference Centre comprises 12 meeting rooms of varying sizes which are perfect for pre-match team talks. We also provide physio treatment rooms and catering to accommodate the nutritional needs of your group. • 120 bedrooms including 4 suites • 12 meeting rooms • Free Wi-Fi • Free parking DINING & NUTRITION DW FITNESS: IN-HOUSE LEISURE FACILITIES Crowne Plaza Belfast caters for all your pre-match meals, breakfast, lunches and evening meals as well as private dining and banqueting if required. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 12/08/2010, 16:30

Document Pack Democratic Services Section Chief Executive’s Department Belfast City Council City Hall Belfast BT1 5GS th 6 August, 2010 MEETING OF PARKS AND LEISURE COMMITTEE Dear Councillor, The above-named Committee will meet in the Lavery Room (Room G05), City Hall on Thursday, 12th August, 2010 at 4.30 pm, for the transaction of the business noted below. You are requested to attend. Yours faithfully PETER McNANEY Chief Executive AGENDA: 1. Routine Matters (a) Apologies (b) Minutes 2. Sickness Absence (Pages 1 - 4) 3. Parks and Leisure Department - Improvement Agenda Update (To Follow) 4. Beechmount Leisure Centre Closure - Supernumerary Staff (Pages 5 - 6) 5. Events Policy Update (Pages 7 - 8) 6. Safer Neighbourhoods - Anti-Social Behaviour Update (Pages 9 - 20) 7. Quarterly Vandalism Report (Pages 21 - 24) 8. External Funding Update (Pages 25 - 28) 9. Peace III Programme (Pages 29 - 32) - 2 - 10. Floral Hall (Pages 33 - 34) 11. Green Flag Awards (Pages 35 - 38) 12. Belfast Zoological Gardens - Mountain Tea House (Pages 39 - 40) 13. Terms of Use for Containers (Pages 41 - 44) 14. Biodiversity Statutory Duty (Pages 45 - 52) 15. Skegoneil Health Centre and Grove Demolition Works (Pages 53 - 56) 16. Playground Improvement Programme (Pages 57 - 66) 17. Tender for Veterinary Services (Pages 67 - 68) 18. BIAZA Meeting (Pages 69 - 72) 19. ICCM Conference (Pages 73 - 74) 20. Respect Through Sport (Pages 75 - 76) 21. Boost Card - Means-Tested Benefit Criteria (Pages 77 - 80) 22. Media Report (Pages 81 - 82) 23. Support for Sport (Pages 83 -

2019/20 Sports Directory

2019/20 SPORTS DIRECTORY Mayor’s Foreword Sports Directory 2019/20 Ards and North Down Borough Council actively encourages local people of all ages and abilities to participate in sport and physical activity, working across a range of ways to open up opportunities for participation – through our five leisure centres Bangor, Holywood, Newtownards, Comber and Portaferry, to our pitches, parks, play areas and sports development programme. Working directly with local sports clubs, through the Ards and North Down Sports Forum, we support their development and growth, offering a Directory is a result of this partnership. Now in its seventh year and containing 81 clubs, the Sports Directory shows very clearly the host of different sports which are thriving in the Ards and North Down area, and provides local people with comprehensive information about how to get involved in the sport of their choice. I hope this latest edition of the Sports Directory will continue to promote our local sports clubs and encourage more people living in the area to get involved, and enjoy physical activity, in order to help create a much healthier Borough. Mayor of Ards and North Down Alderman Bill Keery Ards and North Down Borough Council is not responsible for the delivery/management of activities provided by any of the sports/clubs listed within this directory. All details are correct at time of print, November 2019. 2 Contents Archery 14 Inline Hockey 57 Athletics 15 Martial Arts 58–62 Bowls 16–20 Netball 63–65 Canoeing & Kayaking 21 Orienteering 66 Cricket 22–24 Rowing 67 Cycling 25–26 Rugby 68–71 Dancing 27 Running 72–74 Diving 28–29 Sailing 75–78 Equestrian 30 Shooting 79–80 Fencing 47 Softball 81 Football 31–40 Swimming 82 Gaelic Sports 41–44 Tennis 83–87 Golf 45–50 Volleyball 88 Gymnastics 51–52 Watersports 89 Hockey 53–56 Weightlifting 90 Ards and North Down Borough Council has a firm commitment to support local athletes and sports clubs within the Borough by providing financial assistance through a number of different funding streams.