Instructional Eucharist.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christ the King

the last sunday after pentecost: Christ the King Festival Holy Eucharist November 25, 2018 11:15 a.m. Washington National Cathedral about christ the king Today marks the end of the long season after the Day of Pentecost and the last Sunday of the Church’s liturgical calendar. Known as Christ the King Sunday, it celebrates the all-embracing authority of Christ as Lord of all things, for in Christ all things began and in Christ all things will be fulfilled. We now find ourselves on the threshold of Advent, the season of hope for Christ’s return. The people's responses are in bold. The Entrance Rite carillon prelude Crown him with many crowns Diademata; arr. Edward M. Nassor (b. 1957) organ prelude Cantabile Cesar-Auguste Franck (1822-1890) Pièce heroïque C.-A. Franck introit Cantate Domino Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni (1657-1743) Sung in Latin. Sing to the Lord, sing a new song. Praise him with the saintly congregation. Let Israel rejoice in him, And let the children of Zion rejoice and be glad in their King. (Para. Psalm 148) The people stand as able. processional hymn • 494 Crown him with many crowns Diademata the opening acclamation Blessed be God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. And blessed be God’s kingdom, now and forever. the collect for purity Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love you, and worthily magnify your holy Name; through Christ our Lord. -

Divine Liturgy

THE DIVINE LITURGY OF OUR FATHER AMONG THE SAINTS JOHN CHRYSOSTOM H QEIA LEITOURGIA TOU EN AGIOIS PATROS HMWN IWANNOU TOU CRUSOSTOMOU St Andrew’s Orthodox Press SYDNEY 2005 First published 1996 by Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia 242 Cleveland Street Redfern NSW 2016 Australia Reprinted with revisions and additions 1999 Reprinted with further revisions and additions 2005 Reprinted 2011 Copyright © 1996 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data The divine liturgy of our father among the saints John Chrysostom = I theia leitourgia tou en agiois patros imon Ioannou tou Chrysostomou. ISBN 0 646 44791 2. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church. Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. 2. Orthodox Eastern Church. Prayer-books and devotions. 3. Prayers. I. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia. 242.8019 Typeset in 11/12 point Garamond and 10/11 point SymbolGreek II (Linguist’s Software) CONTENTS Preface vii The Divine Liturgy 1 ïH Qeiva Leitourgiva Conclusion of Orthros 115 Tevlo" tou' ÒOrqrou Dismissal Hymns of the Resurrection 121 ÆApolutivkia ÆAnastavsima Dismissal Hymns of the Major Feasts 127 ÆApolutivkia tou' Dwdekaovrtou Other Hymns 137 Diavforoi ÓUmnoi Preparation for Holy Communion 141 Eujcai; pro; th'" Qeiva" Koinwniva" Thanksgiving after Holy Communion 151 Eujcaristiva meta; th;n Qeivan Koinwnivan Blessing of Loaves 165 ÆAkolouqiva th'" ÆArtoklasiva" Memorial Service 177 ÆAkolouqiva ejpi; Mnhmosuvnw/ v PREFACE The Divine Liturgy in English translation is published with the blessing of His Eminence Archbishop Stylianos of Australia. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Little Compline for Akathist Saturday

The Office of Little Compline with the Akathist Canon and Hymn **As served on the fifth Friday of Great Lent** **Instructions** An icon of the Theotokos (preferably the one described in the Synaxarion below) is placed on a stand in the middle of the solea. The candles are lit and the church is semi-illumined. The censer is used only for the stases of the Akathist Hymn. The curtain and Holy Doors are closed until the priest begins the first stasis of the Akathist Hymn. The priest wears a blue epitrachelion over his exorasson and starts Little Compline in front of the icon. Priest: Blessed is our God always, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Choir: Amen. Priest: Glory to Thee, O God, glory to Thee. O heavenly King, the Comforter, Spirit of Truth, Who art in all places, and fillest all things, Treasury of good things, and Giver of life, come, and dwell in us, and cleanse us from every stain; and save our souls, O good One. People: Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal: have mercy on us. (THRICE) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; both now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen. All-holy Trinity, have mercy on us. Lord, cleanse us from our sins. Master, pardon our iniquities. Holy God, visit and heal our infirmities for Thy Name’s sake. Lord, have mercy. (THRICE) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; both now and ever, and unto ages of ages. -

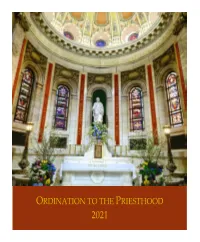

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

The Sunday of the Passion Palm Sunday Holy Eucharist

THE SUNDAY OF THE PASSION palm sunday holy eucharist washington national cathedral THE SUNDAY OF THE PASSION: PALM SUNDAY SUNDAY, APRIL 13, 2014 organ prelude Valet will ich dir geben, BWV 735 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Valet will ich dir geben, BWV 736 J. S. Bach The people stand. THE LITURGY OF THE PALMS introit Hosanna to the Son of David Michael McCarthy (b. 1966) Hosanna to the Son of David, blessed be the King that cometh in the name of the Lord; thou that sittest in the highest heavens, Hosanna in excelsis Deo. the opening acclamation Presider Hosanna to the Son of David. Blessed is the One who comes in the name of the Lord: People Hosanna in the highest. Presider Let us pray. Dear friends in Christ, during Lent we have been preparing by works of love and self-sacrifice for the celebration of our Lord’s Paschal Mystery. Today we come together to begin this solemn celebration in union with the whole church throughout the world. Christ enters his own city to complete his work as our Savior; to suffer, to die, and to rise again. Let us go with him in faith that, united with him in his sufferings; we may share his risen life. People Amen. the gospel of the triumphal entry Matthew 21:1-11 Gospeller The Holy Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Matthew. People Glory to you, Lord Christ. When Jesus and his disciples had come near Jerusalem and had reached Bethphage, at the Mount of Olives, Jesus sent two disciples, saying to them, “Go into the village ahead of you, and immediately you will find a donkey tied, and a colt with her; untie them and bring them to me. -

Mass of Ordination to the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020

Mass of Ordination To the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020 Prayer for the Holy Father O God who in your providential design willed that your Church be built upon blessed Peter, whom you set over the other Apostles, look with favor, we pray, on Francis our Pope and grant that he, whom you have made Peter’s successor, may be for your people a visible source and foundation of unity in faith and of communion. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English Translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved. Most Reverend Michael R. Cote, D.D. Bishop of Norwich Prayer for the Bishop O God, eternal shepherd of the faithful, who tend your Church in countless ways and rule over her in love, grant, we pray, that Michael, your servant, whom you have set over your people, may preside in the place of Christ over the flock whose shepherd he is, and be faithful as a teacher of doctrine, a Priest of sacred worship and as one who serves them by governing. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved 1 CELEBRATION OF THE ORDINATION TO THE PRIESTHOOD OF Reverend Michael Patrick Bovino for Service as Priest of the Diocese of Norwich Ritual Mass for the Conferral of Holy Orders Cathedral of Saint Patrick Norwich, Connecticut June 27, 2020 10:30 a.m. -

= P^Fkqp=Mbqbo=^Ka=M^Ri=Loqelalu=`Ero`E

+ = = p^fkqp=mbqbo=^ka=m^ri=loqelalu=`ero`e NEWSLETTER February, 2012 Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America Archpriest John Udics, Rector 305 Main Road, Herkimer, New York, 13350 Parish Web Page: www.cnyorthodoxchurch.org Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church Newsletter, February, 2012 This month’s Newsletter is in memory of Tillie Leve donated by Steve Leve. Parish Officer Contact Information Rector: Archpriest John Udics: (315) 866-3272 - [email protected] Committee President and Cemetery Director: John Ciko: (315) 866-5825 - [email protected] Committee Secretary: Subdeacon Demetrios Richards (315) 865-5382 – [email protected] Sisterhood President: Rebecca Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Choir Director: Reader John Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Birthdays in February – God Grant You Many Years! 8 – Audrey Gale 20 – Wayne Nuzum 10 – Larissa Lyszczarz 22 – Martha Mamrosch 11 – Eileen Brinck 27 – Marilyn Stevens 13 – Emilee Penree Memory Eternal. 1 Julia Hladysz (1981) 13 Helen Brown (1993) 1 Leonard Corman (1991) 14 Julia Bruska (2000) 1 Dorothy Quackenbusg (2005) 15 Owen Dulak 2 John Garbera (1988) 16 John Yaworski (1977) 2 Helen Woods (1998) 16 Anna Kuzenech (1996) 4 Andrew Keblish (1975) 17 Andrew Yaneshak (1984) 4 Paul Shust Jr (2008) 18 Michael Kuncik (1980) 5 Stephen Sleciak Sr (1972) 21 Peter Slenska (1986) 5 Efrosina Krenichyn (1977) 22 Julia Hudyncia (1983) 5 Olga Nichols (1994) 23 Mary Mezick )2000) 8 Antonina Steckler (2007) 24 John Hubiak 10 Harry Hardish (1975) 26 Helen Pelko (2005) 10 Helen Halkovitch (1989) 28 Andrew Homyk (1984) 10 Theodosia Jago (2007) 28 Cornelius Mamrosch (1995) 13 Natalie Raspey (1973) 28 Louis Brelinsky (2004 13 Andrew Bobak (1978) + Questions and Answers 75. -

The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments

Durham E-Theses The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments Metallidis, George How to cite: Metallidis, George (2003) The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1085/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY GEORGE METALLIDIS The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consentand information derived from it should be acknowledged. The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene: Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments PhD Thesis/FourthYear Supervisor: Prof. ANDREW LOUTH 0-I OCT2003 Durham 2003 The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene To my Mother Despoina The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 12 INTRODUCTION 14 CHAPTER ONE TheLife of St John Damascene 1. -

The Holy Eucharist Rite One INTRODUCTION This Morning We Are Going to Depart from Our Usual Worship

The Holy Eucharist Rite One INTRODUCTION This morning we are going to depart from our usual worship. As we celebrate the Holy Eucharist today, we are going to examine the different parts of the service and explain them as we go along. Our aim is to help us better understand the worship and help us to participate more fully in the Holy Eucharist. The Holy Eucharist is the principle act of Christian worship. As we proceed, we will pause for explanation of why we are doing what we are doing. There will be some historic and some theological explanations. This is a departure from our usual worship but hopefully it will help us all better appreciate and understand the richness of our liturgy. Vestments priest will vest as you talk The vestments the priest wears are derived from dress clothing of the late Roman Empire. The white outer garment is called an alb. It gets its name from the Latin word albus, which means white. It is derived from the commonest under garment in classical Italy, the tunic. It symbolizes purity, decency and propriety. It also represents being washed clean in the waters of baptism. The girdle or cincture is usually made of white linen or hemp. Functionally, it is for ease of movement when wearing the alb. Symbolically, it represents how we are all bound together in Christ. The stole was derived from a Roman ceremonial garland or scarf worn by Roman officials as an indication of his rank. Priests have worn the stole since at least the fourth century. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

The Anglican Rosary History

1 The Anglican Rosary RICK MILLSAP – TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCH RENO, NV – MARCH 2009 “Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.” – I THESSALONIANS 5 History .................................................................................................................1 Why? ....................................................................................................................2 How?....................................................................................................................2 Sample Prayers ..................................................................................................3 Including Specific Personal Prayers................................................................7 Creating Your Own Rosary Prayers .................................................................7 Internet Resources ............................................................................................8 Books...................................................................................................................9 End Notes............................................................................................................9 History The use of beads or other counting device as a companion to prayer has an ancient history. Those early Christian monastics known as the Desert Mothers and Fathers were reported to have gathered up small pebbles and put them in their pockets. While walking, they would pray and toss a