Divining Proportions in the Information Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Inhalt

34 Rome, Pantheon, c. 120 A.D. Contents 34 Rome, Temple of Minerva Medica, c. 300 A.D. 35 Rome, Calidarium, Thermae of Caracalla, 211-217 A.D. Inhalt 35 Trier (Germany), Porta Nigra, c. 300 A.D. 36 NTmes (France), Pont du Gard, c. 15 B.C. 37 Rome, Arch of Constantine, 315 A.D. (Plan and elevation 1:800, Elevation 1:200) 38-47 Early Christian Basilicas and Baptisteries Frühchristliche Basiliken und Baptisterien 8- 9 Introduction by Ogden Hannaford 40 Rome, Basilica of Constantine, 310-13 41 Rome, San Pietro (Old Cathedral), 324 42 Ravenna, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, c. 430-526 10-19 Great Buildings of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia 42 Ravenna, Sant'Apollinare in Classe, 534-549 Grosse Bauten Ägyptens, Mesopotamiens und Persiens 43 Rome, Sant' Agnese Fuori Le Mura, 7th cent. 43 Rome, San Clemente, 1084-1108 12 Giza (Egypt), Site Plan (Scale 1:5000) 44 Rome, Santa Costanza, c. 350 13 Giza, Pyramid of Cheops, c. 2550 B.C. (1:800) 44 Rome, Baptistery of Constantine (Lateran), 430-440 14 Karnak (Egypt), Site Plan, 1550-942 B.C. (1:5000) 44 Nocera (Italy), Baptistery, 450 15 Abu-Simbel (Egypt), Great Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1250 B.C. 45 Ravenna, Orthodox Baptistery, c. 450 (1:800, 1:200) 15 Mycenae (Greece), Treasury of Atreus, c. 1350 B.C. 16 Medinet Habu (Egypt), Funerary Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1175 B.C. 17 Edfu (Egypt), Great Temple of Horus, 237-57 B.C. 46-53 Byzantine Central and Cross-domed Churches 18 Khorsabad (Iraq), Palace of Sargon, 721 B.C. -

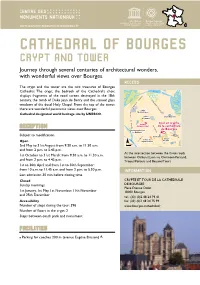

Crypt and Tower of Bourges Cathedral

www.tourisme.monuments-nationaux.fr CATHEDRAL OF BOURGES CRYPT AND TOWER Journey through several centuries of architectural wonders, with wonderful views over Bourges. ACCESS The crypt and the tower are the two treasures of Bourges Cathedral. The crypt, the bedrock of the Cathedral’s choir, displays fragments of the rood screen destroyed in the 18th century, the tomb of Duke Jean de Berry and the stained glass windows of the ducal Holy Chapel. From the top of the tower, there are wonderful panoramic views over Bourges. Cathedral designated world heritage site by UNESCO. RECEPTION Subject to modification. Open 2nd May to 31st August: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.45 p.m. At the intersection between the three roads 1st October to 31st March: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. between Orléans/Lyon via Clermont-Ferrand, and from 2 p.m. to 4.45 p.m. Troyes/Poitiers and Beaune/Tours 1st to 30th April and from 1st to 30th September: from 10 a.m. to 11.45 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. INFORMATION Last admission 30 min before closing time. Closed CRYPTE ET TOUR DE LA CATHÉDRALE Sunday mornings DE BOURGES Place Étienne Dolet 1st January, 1st May, 1st November, 11th November 18000 Bourges and 25th December tel.: (33) (0)2 48 24 79 41 Accessibility fax: (33) (0)2 48 24 75 99 Number of steps during the tour: 396 www.bourges-cathedrale.fr Number of floors in the crypt: 2 Steps between coach park and monument FACILITIES Parking for coaches 200 m (avenue Eugène Brisson) NORTH WESTERN FRANCE CENTRE-LOIRE VALLEY / CRYPT AND TOWER OF BOURGES -

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, the University of Iowa Art

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, The University of Iowa Art Building West, North Riverside Drive, Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone: 319-335-1762 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY Education Princeton University. Ph.D., Architectural History, 1996; M.A. 1993. University of California, Santa Cruz. M.S., Physics, 1990. Passed qualifying exams for candidacy to Ph.D., 1991. Harvard University. B.A. CuM Laude, Physics, 1989. Granville High School, Granville, Ohio. Graduated Valedictorian, 1985. Professional and academic positions University of Iowa. Professor. Fall 1998 to Spring 2004 as Assistant Professor; promoted May 2004 to Associate Professor; promoted May 2012 to Full Professor. Florida Atlantic University. Assistant Professor. Fall 1997-Spring 1998. Sewanee, The University of the South. Visiting Assistant Professor. Fall 1996-Spring 1997. University of Connecticut. Visiting Lecturer. Fall 1995. Washington Cathedral. Technical Consultant. Periodic employment between 1993 and 1995. SCHOLARSHIP I: PUBLICATIONS Books (sole author) 1) Late Gothic Architecture: Its Evolution, Extinction, and Reception (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), 562 pages. 2) The Geometry of Creation: Architectural Drawing and the Dynamics of Gothic Design (FarnhaM: Ashgate, 2011), 462 pages. The Geometry of Creation has been reviewed by Mailan Doquang in Speculum 87.3 (July, 2012), 842-844, by Stefan Bürger in Sehepunkte, www.sehepunkte.de/2012/07/20750.htMl, by Eric Fernie in The Burlington Magazine CLV, March 2013, 179-80, by David Yeomans in Construction History Society, Jan 2013, 23-25, by Paul Binski in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 166, 2013, 212-14, by Paul Crossley in Architectural History, 56, 2013, 13-14, and by Michael Davis in JSAH 73, 1 (March, 2014), 169-171. -

La Structure De La Cathédrale De Chartres

La structure de la cathédrale de Chartres Andrew Tallon Le stigmate d’une sur-construction, d’une masse inutile, voire d’une certaine maladresse pèse toujours sur l’interprétation de la structure de la cathédrale de Chartres1. Il est temps aujourd’hui de dépasser ces explications malheureuses et de réhabiliter la réception de la structure du bâtiment, à l’image d’autres facettes révélées au cours de ces dernières années. La structure de la cathédrale Chartres ne doit plus être envisagée, dans le cadre de comparaisons unilatérales, en faveur d’un éloge du premier maître de la cathé- drale de Bourges2, ni limitée à un indice chronologique pratique sinon trompeur au cœur d’un débat perdurant depuis plus d’une cinquantaine d’années. Elle ne doit pas plus être envisagée comme le produit d’une peur intense de l’échec face à un déploiement inédit de fenêtres hautes. Au contraire, la structure de la cathé- drale de Chartres doit être vue dans le contexte d’un ensemble architecturale : elle résulte à la fois d’un système précisément pensé, voire brillant, conçu non seulement pour résister parfaitement aux forces affaiblissantes du temps et de la gravité – ce que nous nous efforcerons de montrer à l’aide d’un relevé laser haute-définition entrepris en juin 2011 (fig. 1 et 2) – mais aussi d’une structure illusionniste, une évocation puissante de la sublime architecturale3. 1.– Voir, en particulier, R. Mark et W. Clark, « Gothic Structural Experimentation », Scientific American, 251, 5, 1984, p. 176-185. 2.– R. Mark, Experiments in Gothic Structure, Cambridge, Mass., 1982, p. -

É an Installation by JR #Aupanth·On Ê

Press release, 25 February 2014 The CM N is inviting JR to create a participatory work at the Pantheon çTo the Pantheon!é an installation by JR #AuPanth·on ê www.au-pantheon.fr Press officer: Camille Boneu ê +33 (0)1 44 61 21 86 ê camille.boneu@ monuments-nationaux.fr çTo the Pantheon!é An installation by JR The restoration work currently being carried out on the Pantheon is one of the largest projects in Europe. The purpose of the current phase is to consolidate and fully restore the dome. A vast self-supporting scaffolding system ê a great technical feat ê has been built around the dome and will remain in place for two years. Last October the President of the Centre des Monuments Nationaux, Philippe Bélaval, presented the President of the French Republic with a report on the role of the Pantheon in promoting the values of the Republic. The title of this public report was “Pour faire entrer le peuple au Panthéon” (Getting people into the Pantheon), and it contains suggestions on how to make the monument more attractive, encourage French people to truly identify with it, and give it a greater role in Republican ceremonies. In order to give concrete form to these proposals, which have since been approved by the public authorities, the CMN has chosen to ask a contemporary artist to carry out a worldwide project embodying the values of this monument, which is so emblematic of the French Republic. Hence for the first tim e the worksite hoardings installed around a national m onum ent will be used to present a contem porary artistic venture instead of a lucrative advertising cam paign. -

The Cathedral of Bourges

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 6 (2011): Jennings CP1-10 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING The Cathedral of Bourges: A Witness to Judeo-Christian Dialogue in Medieval Berry Margaret Jennings, Boston College Presented at the “Was there a „Golden Age‟ of Christian-Jewish Relations?” Conference at Boston College, April 2010 The term “Golden Age” appears in several contexts. In most venues, it both attracts and inspires controversy: Is the Golden Age, as technology claims, the year following a stunning break- through, now available for use? Is it, as moralists would aver, a better, purer time? Can it be identified, as social engineers would hope, as an epoch of heightened output in art, science, lit- erature, and philosophy? Does it portend, in assessing human development, an extended period of progress, prosperity, and cultural achievement? Factoring in Hesiod‟s and Ovid‟s understand- ing that a “Golden Age” was an era of great peace and happiness (Works and Days, 109-210 and Metamorphoses I, 89-150) is not particularly helpful because, as a mythological entity, their “golden age” was far removed from ordinary experience and their testimony is necessarily imag- inative. In the end, it is probably as difficult to define “Golden Age” as it is to speak of interactions between Jews and Christians in, what Jonathan Ray calls, “sweeping terms.” And yet, there were epochs when the unity, harmony, and fulfillment that are so hard to realize seemed almost within reach. An era giving prominence to these qualities seems to deserve the appellation “golden age.” Still, if religious differences characterize those involved, the possibility of disso- nance inevitably raises tension. -

Teaching Medieval Architecture in the Information

Sherry C.M. Lindquist, Editor SPECIAL REPORTS (continued) falls in fluid and Teaching Medieval Architecture in the balanced folds at Information Age her feet. The carv- ing is of the high- As a graduate student in the Department of Art and est standard and Archeology at Columbia University in the early 2000s, the figure is an with an appointment in the Media Center for Art History, example of the and with Stephen Murray as mentor, the world of digital finest Mosan humanities could not have been more exciting. I had the sculpture of the good fortune to have been engaged in a host of projects, thirteenth century. from the Amiens Cathedral Trilogy animation and CD- ROM to the less well-known but equally compelling Like all wood NEH-funded Real Virtual/History of Architecture project sculpture of the (http://www.mcah.columbia.edu/ha), for which we thirteenth century created a series of spherical panoramic photographs of a and earlier, this wide range of key buildings—a collection that would Virgin and Child eventually be shared in part with ArtStor. It was an excel- does not survive lent education in the promises and perils of technology in perfect condi- applied to the humanities: thanks to Murray’s vision, the tion. The head of distinction between digitized humanities and digital human- the child and the ities remained eminently crisp. Virgin’s right hand were once dow- The world of digital humanities has changed much in the elled into place. intervening years—so much so that it seems time to drop These are now the technological qualifier from the couplet. -

Outstanding Heritage Sites - a Resource for Territories Magali Talandier, Françoise Navarre, Laure Cormier, Pierre-Antoine Landel, Jean-François Ruault, Nicolas Senil

Outstanding heritage sites - A resource for territories Magali Talandier, Françoise Navarre, Laure Cormier, Pierre-Antoine Landel, Jean-François Ruault, Nicolas Senil To cite this version: Magali Talandier, Françoise Navarre, Laure Cormier, Pierre-Antoine Landel, Jean-François Ruault, et al.. Outstanding heritage sites - A resource for territories. Editions du PUCA, 2019, Recherche, 978-2-11-138177-3. halshs-02298543 HAL Id: halshs-02298543 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02298543 Submitted on 26 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Outstanding heritage sites condense issues pertaining to economic development, financial management, governance, appropriation and preservation, affecting the territories which they are part of. These tensions, given free rein, would undermine the purpose served by the sites as well as their sustainability. In this context and after the analysis stage, the publication lays down the necessary conditions for these remarkable sites to constitute resources for the territories hosting them, and -

Chartres and High Gothi 1190+ the “High Gothic” Cathedrals

Chartres and High Gothi 1190+ The “High Gothic” Cathedrals: Chartres, 1194+ Soissons, 1191+ (?) Bourges, 1194 Reims, 1210 Amiens, 1220 Beauvais, 1225 108 116 137+ gigantism in Gothic Architecture Bourges Cathedral, begun 1194 Chartres Cathedral, begun 1194 Soissons Chartres Bourges The “High Gothic Revolution:” 3 stories clerestory as tall as arcade (but not Bourges) quadripartite vaults (mostly) Chartres, 116’, 1194+ Soissons, 97’,1191+ Bourges, 118’, 1195+ 1. Simplification • 3-story elevations • Quadripartite vaults • Flying buttresses 2. Monumentality- buildings over 110’ tall 3. Assertiveness – (down go the Gallo-Roman Walls!) Chartres Cathedral, 1194 + The tunic of the Virgin: the sancta camisa, given to cathedral 876 Le puits des Saints forts Ergotism - St. Anthony’s fire Bishop Fulbert (1007-1028) dedicates the cathedral of 1020 West towers rebuilt after fire of 1134 with portals of c. 1145 Royal portals 1145 The foundations of Fulbert’s cathedral of 1020 (in grey) underneath the present cathedral (in orange) rebuilt in 1194+ Fulbert’s cathedral of 1020 Original location of portals Final location of ROYAL portals Christ in Majesty The Virgin THE ROYAL Ascension PORTALS OF The Royal CHARTRES Portal: 1145 c. 1145 Bishop Fulbert’s Cathedral of 1020, built around older Carolingian church The puit des Saints forts Flamboyant style N. spire (16th century) South tower North c. 1140 Tower 1134 1194 + Royal portals and west windows, c. 1145 Chartres, the town The bishop had full jurisdiction until c 1020’s, then king gave the county of -

Burgundian Gothic Architecture

BURGUNDIAN GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE ROBERT BRANNER DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK A. ZWEMMER LTD LONDON tjj V1 © 1960 A. ZWEMMER LTD, 76-80 CHARING CROSS ROAD, LONDON WC2 MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BLOCKS ETCHED BY W. F. SEDGWICK LTD, LONDON SEI TEXT AND ILL USTRATIONS PRINTED BY PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES AND CO. LTD, BRADFORD BOUND BY KEY AND WHITING LTD, LONDON NI Contents List of Plates I. Auxerre Cathedral, the interior of the chevet 2a. Anzy Ie Due, the nave 2b. Paray Ie Monial, the nave 3a. Fontenay, the nave 3b. Pontigny, the nave 4a. Fontenay, the chapter house 4b. Vermenton, detail of the nave sa. Bar sur Aube, St Pierre, the exterior of the chevet sb. Bar sur Aube, St Maclou, detail of the nave 6a. Chablis, St Pierre, the nave 6b. Montreal, the crossing and apse 7a. Langres Cathedral, the interior 7b. Bar sur Aube, St Maclou, the nave Sa. Sens Cathedral, the interior of the chevet sb. Chablis, St Martin, the hemicycle 9a. Auxerre, St Eusebe, the nave 9b. Vezelay, the interior of the chevet 10. Pontigny, the interior of the chevet lIa. Canterbury, a detail of Trinity Chapel IIb. Geneva, former Cathedral, a detail of the choir 12a. Troyes, Madeleine, a detail of the choir I2b. Sens Cathedral, a detail of the north tower wall 13a. Auxerre Cathedral, the north aisle of the chevet 13b. Clamecy, St Martin, the ambulatory wall 14. Auxerre Cathedral, an exterior detail of the hemicycle clerestory IS. Auxerre Cathedral, a detail of the clerestory and triforium 16a. -

An Iconographic Analysis of the Corbels of Chartres Cathedral

FACE VALUE: AN ICONOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE CORBELS OF CHARTRES CATHEDRAL ________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS _______________________________________________________________________ by Larissa C. Pluta August 2013 Thesis Approvals: ________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth S. Bolman, Thesis Advisor, Art History ________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Marcia B. Hall, Art History ABSTRACT The numerous figurated corbels of Chartres Cathedral were inscribed with semiotic content. Works in this genre were formerly disregarded by researchers because of their perceived lack of meaning. Trends in modern scholarship have challenged this misconception, and recent technological innovations have facilitated the study of these objects. The category would be more appropriately termed “secondary” rather than” marginal,” as the former offers a semantically unencumbered assessment of the role of these sculptures. Originally designed for the cathedral’s twelfth-century western complex, the corbels were likely members of a series that encircled the entire perimeter of the building. The use of human and animal head motifs for their decoration exemplifies a pervasive historical practice in architectural sculpture. The preservation of the corbels in the Gothic reconstruction of the cathedral substantiates their -

Deciphering the Iron Provenance on a Medieval Building Yard: the Case of Bourges Cathedral

minerals Article Deciphering the Iron Provenance on a Medieval Building Yard: The Case of Bourges Cathedral Maxime L’Héritier 1, Philippe Dillmann 2,* and Guillaume Sarah 3 1 Department of History, Université Paris 8, ARSCAN CNRS UMR 7041, CEDEX 93526 Saint-Denis, France; [email protected] 2 LAPA-IRAMAT, NIMBE, CEA, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, CEA Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 3 IRAMAT-CEB UMR5060, Université d’Orléans, CEDEX 2, 45071 Orléans, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 November 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: This paper presents the provenance study of the iron reinforcements of Bourges Cathedral (13th c.): the links of a 100 m long iron chain, surrounding the eastern parts of the cathedral at the triforium level and 4.5 to 5 m long tie-rods consolidating the arches of the inner aisle at the same level. The analytical methodology is based on the determination of trace rare earth elements analyses by LA-ICP-MS in the slag inclusions of the artefacts and in the slag found on candidate production sites combined with statistical approaches. This chemical approach is crossed with archaeological and historical studies on the monument itself and on the production sites. Ninety-nine iron samples were analyzed on the bars and chains and 238 iron slags from 3 presumed areas of supply. For the first time, iron circulation and trade around a single building yard over a time of 30 to 40 years is studied with a precision never obtained before with historical sources.