Newsletter 28.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PD-September 17 A4 Pages.Indd

CHURCH OF ENGLAND DEVON This week sign-up to receive daily emails to inspire your prayers and rayers action throughout the season of P Creationtide (1 Sept – 4 Oct). This year’s theme is ‘Inspiring Earth’. Go to https:// Fri 1st – Sat 9th September ecochurchsouthwest.org.uk/creationtide 1. 1. On this first day of the ‘Season of Creation,’ Patteson, martyred in Melanesia and from dedicated to God as Creator and Sustainer of this Diocese, and on 23rd pray for the all life, we pray: God said, ‘Let there be light.’ Melanesian Mission AGM and Festival day. Eternal God, we thank you for your light and 7. For the Central Exeter Mission Community, your truth. We praise you for your fatherly their priest Sheila Swarbrick and for all who care in creating a universe which proclaims live and worship in Central Exeter. your glory. Inspire us to worship you, the creator of all, and let your light shine upon 8. For the Chudleigh Mission Community, their our world. clergy Paul Wimsett, Martin Fletcher, Readers Arnold Cade, Sheila Fletcher, Helen Harding 2. For the Braunton Mission Community, their and for all who live and worship in Trusham, priest Anne Thorne, Reader David Rushworth Chudleigh Knighton and Chudleigh. and for all who live and worship in Braunton 9. In our link with Thika pray for the Bishop 3. 3. For the Brixham Mission Community, their Julius Wanyoike and his secretary James clergy Ian Blyde, John Gay, Angela Sumner, Kamura. Give thanks for the work of the Readers Susan Shaw, Wendy Emlyn and for Mothers’ Union – the powerhouse of the all who live and worship in Lower Brixham, Church – and pray for Esther Wanyoike All Saints, Kingswear, Churston Ferrers and the president and Cecilia Mwaniki the co- Brixham St Mary. -

Church of England Devon Prayers

CHURCH OF ENGLAND DEVON PRAYERS CHURCH OF ENGLAND Sun 27th – Thur 31st May DEVON This week as we think about God as Trinity, help us to remember that God is always in community and to recommit ourselves to the communities in which we live and are involved in. rayers P Tue 1st – Sat 5th May 27. On Trinity Sunday we pray: Father, you sent 30. For the Culm Valley Mission Community, their givvirgin dedication of St Andrew’s Church in Ipplepen. your Word to bring us truth and your Spirit to clergy Simon Talbot, Mike North, Reader Chris 1. For the Braunton Mission Community, their 4. In our link with Thika we are asked to pray for make us holy. Through them we come to know Russell and for all who live and worship in priest Anne Thorne, Reader David Rushworth the Namrata Shah Children’s Home: for the the mystery of your life. Help us to worship you, Willand, Uffculme and Kentisbeare. and for all who live and worship in Braunton. manager Jedidah and the children who come one God in three Persons, by proclaiming and 2. For the Brixham Mission Community, their to the home from very difficult situations. 31. For the Dart Valley Mission Community, their Please pray also for the older children boarding living our faith in you. clergy Ian Blyde, John Gay, Angela Sumner, clergy Tom Benson, Fiona Wimsett, Readers at secondary schools and those who have 28. In our link with the Diocese of Bayeux-Lisieux John Vinton, David Harwood, Jenny Holton and Readers Wendy Emlyn, Susan Shaw and for all who live and worship in Lower Brixham, gone onto further education or are looking for in France we pray for the Centre of Theological for all who live and worship in Staverton with All Saints, Kingswear, Churston Ferrers and employment. -

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

57 Fore Street, Totnes, Devon TQ9 5NL. Tel: 01803 863888 Email: [email protected] REF: DRO1187 LAND at ALSTON ALSTON LANE CHURSTON FERRERS BRIXHAM TQ5 0HT

57 Fore Street, Totnes, Devon TQ9 5NL. Tel: 01803 863888 Email: [email protected] REF: DRO1187 LAND AT ALSTON ALSTON LANE CHURSTON FERRERS BRIXHAM TQ5 0HT SIX USEFUL SIZED PADDOCKS WITH PANORAMIC VIEWS ACROSS TORBAY AND BEYOND. EXTENDING IN TOTAL TO 48.50 ACRES (19.64 HECTARES) WITH THE BENEFIT OF MAINS WATER AND GOOD ACCESS. AVAILABLE IN SIX CONVENIENT LOTS, COMBINATION OF LOTS OR AS A WHOLE FOR SALE BY TENDER - TENDERS CLOSING ON FRIDAY 9th NOVEMBER 2012 AT 5:00PM LOT 1 – O.I.R.O. £65,000 LOT 4 – O.I.R.O. £65,000 LOT 2 – O.I.R.O. £65,000 LOT 5 – O.I.R.O. £35,000 LOT 3 – O.I.R.O. £65,000 LOT 6 – O.I.R.O. £35,000 Land at Alston Alston Lane Churston Ferrers Brixham Situation The land is situated between Brixham and Galmpton, close to the A379 Churston to Kingswear road. The land is approximately 2.0 miles to the west of Brixham and 8 miles from Totnes. Directions Head out of Totnes on the Totnes to Paignton road passing through Collaton St Mary. As you enter Paignton turn right at the main traffic lights and proceed up the Hill. Continue along the Brixham Road (A3022) following signs for Brixham. At the end of the Brixham road turn right and proceed along this road, passing Churston Golf Club on your left. After passing the Ford Car Garage on your left take the following right hand turn signposted ‘Dartmouth’ and ‘Kingswear’. Proceed up the Hill and the land will be found on your left hand side after the left hand bend in the road. -

DRFU Handbook 2011-12 Cc.Pmd

DEVON RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION LTD FOUNDED 1877 COUNTY CHAMPIONS 1899 1901 1906 1907 1911 1912 1957 2004 2005 2007 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2011-12 Max Turner President Devon R.F.U. 2011-12 Devon Rugby Football Union Limited, Registered under the Industrial & Provident Societies Act 1965, Registered No: 30997R Registered Office 58 The Terrace Torquay Devon TQ1 1DE * * * * * THE DEVON RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION IS A BROADLY BASED BODY TO PROMOTE, MANAGE AND BE ACCOUNTABLE FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GAME AND TO MAINTAIN ITS TRUE SPIRIT FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL PARTICIPANTS. THE PHILOSOPHY OF COUNTY ADMINISTRATORS HAS TO BE THE PROMOTION OF THOSE INTERESTS WITHOUT REGARD TO CLUB MEMBERSHIP OR ALLEGIANCE. * * * * * VIEW THE DEVON RFU WEBSITE AT THE FOLLOWING LINK http://clubs.rfu.com/Clubs/portals/devonrfu/ DEVON RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION LTD 2011-12 Founded 1877 President; Max Turner, Higher Collibeer, Spreyton, Crediton, EX17 5BA Tel; 01837 840625 - 07863 356044 Email; [email protected] President Elect; Maureen Jackson, 6, Ernesettle Rd, Higher St. Budeaux, Plymouth, PL5 2EZ Tel; 01752 206438 - 07780 776137 Email; [email protected] Immediate Past President; Terry Brown 30, Abbots Park, Cornwood, Ivybridge, PL21 9PP. Tel; 01752 837742 Email; [email protected] Devon Representative to the RFU; Geoff Simpson, 108, Pattinson Drive, Mainstone, Plymouth, PL6 8RU Tel; 01752 211526 - Email; [email protected] Hon. Secretary; Treve Mitchell, 5, Speakers Rd., Ivybridge, PL21 0JP. Tel; 01752 894676 email - [email protected] Hon. Treasurer; Ken Jeffery 19, Court Rd., Chelston, Torquay, TQ2 6SE. Tel; 01803 605975 Email; [email protected] Hon. -

Greenway Barton Maypool, Devon Greenway Barton the Property the House Was Converted Around 1998 and Maypool, Devon TQ5 0ET Has Been in the Same Ownership Ever Since

Greenway Barton Maypool, Devon Greenway Barton The Property The house was converted around 1998 and Maypool, Devon TQ5 0ET has been in the same ownership ever since. The property has been well maintained by the A well maintained detached current owners and used as a second home. house close to the Dart Estuary The entrance hall leads to a dining hall with vaulted ceilings. A large sitting room with wood Dartmouth and Dittisham by Ferry (1 mile walk to burning stove has good countryside views. the ferry), Galmpton 1 mile, Churston Ferrers 1 mile The kitchen/breakfast room gives access to the Reception hall | Kitchen/breakfast room gardens which are manageable and surround Dining room | Sitting room | Garden room the house. There is a garden room too with Master bedroom with ensuite | 4 further beautiful views down to the River Dart Estuary. bedrooms (1 ensuite) | 2 further bathrooms There are 5 bedrooms in total, 2 with ensuite Boat store/double garage | Off street parking for bath/shower rooms. 3 are on the ground floor at least 5 cars | Well maintained gardens and 2 on the first floor. Location Outside the gardens are split into various Approximately quarter of a mile from the Dart sections and there is a good selection of flowers Estuary and 1 mile from the favoured village of and shrubs. Galmpton, in the lovely Dart Valley. There is a large driveway suitable for parking at The River Dart is well known for its calm least 4 cars and a large garage/boat store. sailing waters and access to the south coast at Dartmouth. -

Proposed Schemes for 2018/19

Proposed Schemes for 2018/19 Schemes in priority order and subject to funding. 20 mph zones outside schools An ongoing program of schemes will continue to be developed and presented for consideration by the Executive Lead and schemes identified for 2018/2019 will include: Primary/Junior Schools. Babbacombe Primary School, Torquay (Quinta Road may be suitable for treatment but not Reddenhill Road) Cockington Primary School, Torquay (Old Mill Road entrance – variable 20mph when lights flash) Secondary Schools Spiers College (formerly Westlands), Torquay As this programme begins to draw towards completion, it should be noted that the following schools are yet to be treated, however it should be noted that some of these cannot be treated and these have the reasons included below. Primary/Junior Schools Collaton St Mary, Paignton - Investigated 2016/17 but road too narrow to implement required signage, no option to improve. Furzeham, Brixham - Investigated 2016/17, traffic does not pass school entrance which is effectively in a cul-de-sac, the proposal is to investigate a possible variable 20mph scheme for Higher Furzeham Road, South Furzeham Road and Rope Walk. Galmpton, Brixham - Further discussions are required with Devon County Council due to the close proximity of the derestricted speed limit on the approach to the village. However, high levels of congestion lead to lower speeds at school times. This scheme may need to be included as part of a larger scheme which includes Churston Ferrers Grammar School. Kings Ash Infants, Nursery and Junior, Paignton* - School crossing patrol may be deleted, traffic calmed therefore permanent 20mph limit could be considered. -

Churston Golf Club

THE ISSUE 5 - SPRING 2007 GGAA ZZ EE TT TT EE The Neighbourhood Magazine serving Galmpton, Churston, and Broadsands Cover Price : 50p Galmpton (where sold) Windmill Circulation 1,500 Sponsored by Galmpton Village Institute, Greenway Road Galmpton Gooseberry Pie Fair Committee Galmpton Floral Day Working Party Galmpton Congregational Evangelical Church, Flavel Chapel St Mary C of E Church, Churston (incorporating its Good News) Galmpton Residents’ Association (incorporating its Newsletter) Galmpton Pre-School Ltd, Greenway Road Churston Ferrers Grammar School & PTA, Greenway Road Bancrofts Heating & Plumbing, Paignton Bradleys Estate Agents, Hyde Road, Paignton Cayman Golf (Churston), Dartmouth Road Churston Golf Club, Dartmouth Road Dart Sailability, Noss Marina, Kingswear Eric Lloyd & Co Ltd, Churston Broadway Galleon Stores & Galmpton Post Office, Stoke Gabriel Road Galmpton Touring Park, Greenway Road gap-architecture, The Orchards, Stoke Gabriel Road Kathryn Protheroe Curtains & Soft Furnishings, Totnes Outshine Window Cleaning, Stoke Gabriel Road Roger Richards Solicitors, Churston Broadway ServiceMaster Clean, Torbay The Friends of Churston Library, Churston Broadway The Manor Inn, Stoke Gabriel Road The National Trust, Greenway The White Horse Hotel, Dartmouth Road Zahra Sugaring, Jeanette Dempsey, Greenway Road Magazine Contents Editorial 3 Galmpton Floral Day 2006 Christmas in Words & Music 4 Galmpton Floral Days 2007 Gooseberry Pie Fair 2007 5 Mothering Sunday Yoghurt Cake 6 The Manor Inn 7 The National -

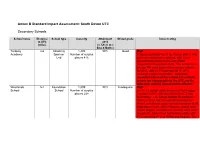

South Devon UTC

Annex B Standard Impact Assessment: South Devon UTC Secondary Schools School name Distance School type Capacity Attainment Ofsted grade Impact rating to UTC 2013 (miles) (% 5A*-C incl Eng & Maths) Torquay 4.6 Academy 1,200 50% Good High Academy Sponsor Number of surplus A Sports Academy for 11 to 18 year olds, it was Led places 416 graded as good and improving, with some outstanding features at the last Ofsted inspection in December 2010. The school is in the top 100 most improved secondary schools for 2013, with a 19% increase for 5+ A*-C including English and Maths. Given the specialist nature of the school it is unlikely to lose too many pupils to the UTC, so the long term viability should not be affected. Westlands 5.4 Foundation 1,509 38% Inadequate High School School Number of surplus An 11–18 school which became a Technology places 238 College in 2001, with specialisms in ICT and technology. The school applied for Academy status in 2013, but this was refused after the school was placed under special measures at its inspection in June 2013. However, recent entry GCSE English and Maths in January 2014 were already 9% higher than last year's results, with 47% achieving A*-C in Maths and English. The school is working in partnership with Ivybridge Community College (recently rated 'Outstanding' by Ofsted, in all measures, for the fifth time in a row; one of the most successful schools in the country), to learn from their good practice. It is likely to lose some pupils to the UTC, but this is unlikely to affect its long term viability given the small number involved. -

Brixham Ward Boundary (Furzeham with Summercombe)

Brixham Ward Boundary (Furzeham with Summercombe) Brixham for such a historic town appears to have been ill treated with regard to its civil boundaries in recent years. Originally, Brixham was a large ecclesiastical parish1 covering the town of Brixham and bounded by the River Dart and Churston Ferrers parish. With the formation of Torbay, a significant part of what was once Brixham has been lost to South Hams, particularly that part to the south and west of Kennels Road (A379), Kingswear Road, and Gattery Lane/Challeycroft Road. However, this still leaves the larger part of the old ecclesiastical parish within Torbay. I would make three points: Seaward boundaries First, for reasons which I cannot fathom, Torbay has chosen to extend their ward boundaries seawards. Given that Brixham is the biggest grossing fishing port in England, one would expect to see the Brixham ward boundaries extended seawards from the town. However, the Churston with Galmpton ward completely encloses the sea around Brixham. Further Brixham Outer Harbour would appear to lie within the bounds of the Churston and Galmpton ward. Consequently, a recent proposal for a new jetty in Brixham Outer Harbour would not be a matter for Brixham but for Churston and Galmpton. This seems totally nonsensical. Boundary between Furzeham with Summercombe and the Churston with Galmpton wards Second, there is a question then as to what the boundary, particularly the western one for Brixham should be. In my view, the determinand should be the boundary of the ecclesiastical parish for Brixham. The current proposals from Torbay for the Brixham ward of Furzeham with Summercombe show the boundary to the north of the A3022 (the main road into Brixham) is more or less where it should be given the boundaries between the Churston Ferrers and Brixham ecclesiastical parishes (although probably one or two small fields close and to the north of the main road which should be in Brixham are excluded). -

Stags.Co.Uk 01803 865454 | [email protected]

stags.co.uk 01803 865454 | [email protected] Redhills, 17 Whilborough Road Kingskerswell, TQ12 5DY An older style detached property offering great potential and has delightful rural views. Newton Abbot 3.5 miles Exeter 19 miles Torquay Seafront 3.5 miles • Detached home • Three bedrooms • Large garden • Rural views • Potential for extension (STPP) • No onward Chain • Garage and parking • Guide price £405,000 Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London Redhills, 17 Whilborough Road, Kingskerswell, TQ12 5DY SITUATION regarded Grammar schools in Torquay and Redhills is located on the outskirts of Churston Ferrers, not forgetting some of the best Kingskerswell in the heart of the rolling South sailing waters in the country. The property is only Devon countryside. It is ideally located between a short walk/drive from North Whilborough and the English Riviera and the market town of beyond Newton Abbot and the A38. Newton Abbot, and is particularly well placed for those that need to commute to the county DESCRIPTION capital of Exeter. Rural, yet not isolated, is very Redhills is a mature detached property, situated much the mantra of this wonderful family home. in an elevated position with delightful rural views. The property does require some updating At Newton Abbot, the A380 is easily accessed and offers a superb opportunity to create a providing speedy access to Exeter and the M5/ larger family home, subject to any necessary M4 Motorway network beyond. There is an consents. Redhills is located in a generously sized intercity railway station at Newton Abbot plot with an attractive well stocked gardens and providing a route to London Paddington.