Overcoming Modernity and the Kyoto School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sakai Semboku Port Tourist Information

Sakai Semboku Port Tourist http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/cruise/ Information Sakai City Traditional Crafts Museum Here you can learn the traditional industries in Sakai such as knives and scissors, incense sticks, wazarashi (Japanese cotton textile)and yukata, rugs, kombu products, bicycles, koinobori carp streamers, as well as Japanese sweets. At the shop Sakai Ichi you can purchase these excellent made-in-Sakai products. Sakai HAMONO Museum featuring the world-renowned Sakai forged knives is on its property. Location/View 1-1-30 Zaimokucho-nishi,Sakai-ku,Sakai,Osaka Access 10 min. via car from port (3km) Season Year-round Sakai City Traditional Crafts Museum http://www.sakaidensan.jp/en Related links SAKAI FORGED KNIVES http://www.sakaiknife.com/index.asp Contact Us【Sakai City Industrial Promotion Center/Market Development Division】 TEL:+81-72-255-1223 E-MAIL: [email protected] Website: http://www.sakai-ipc.jp/en/index.html Sakai City Museum This museum displays a lot of materials regarding Sakai’s history,art,archaeology, and folklore. The museum’s video theater lets the viewers experience the grand scale of the Mozu Kofungun ancient tomb group, with its virtual reality program using high definition CG played on 200-inch large screen. Location/View 2 Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai (Inside Daisen Park) Access 20 min. via car from port (6km) Parking for Season Year-round 18 buses tour buses Related links Contact Us【Sakai City Museum】 TEL:+81-72-245-6201 E-MAIL: [email protected] Website: http://www.city.sakai.lg.jp/hakubutu Sakai City Traditional Town House Museum The amaguchi Residence The Yamaguchi residence, dating from the early Edo period (17th century),was designated as a National Important Cultural Property in 1966.Entering the Yamaguchi residence, you first step into a small earthen-floored hall that leads up to a larger hall with a kitchen stove. -

2009 Outbreak and School Closure, Osaka Prefecture, Japan

LETTERS Influenza (H1N1) 2009 virus was spreading widely to each school’s administrator. The pre- other schools and communities and fecture-wide school closure strategy 2009 Outbreak and that school closures would be neces- may have had an effect on not only the School Closure, sary (1,2). reduction of virus transmission and Osaka Prefecture, The governor of Osaka decided elimination of successive large out- to close all 270 high schools and 526 breaks but also greater public aware- Japan junior high schools in Osaka Prefec- ness about the need for preventive To the Editor: The Osaka Prefec- ture from Monday, May 18, to Sunday, measures. tural Government, the third largest lo- May 24, following the weekend days cal authority in Japan and comprising of May 16 and 17 observed at most Acknowledgments 43 cities (total population 8.8 million), schools. Students were ordered to stay We thank the public health centers in was informed of a novel influenza out- at home (3). Most nurseries, primary Osaka, Sakai, Higashiosaka, and Takatsuki break on May 16, 2009. A high school schools, colleges, and universities for data collection and the National Insti- submitted an urgent report that ≈100 in the 9 cities with influenza cases tute of Infectious Disease, Tokyo, for help- students had influenza symptoms; voluntarily followed the governor’s ful advice. an independent report indicated that decision. Antiviral drugs were pre- scribed by local physicians to almost a primary school child also showed Ryosuke Kawaguchi, all students with confirmed infection; similar symptoms. Masaya Miyazono, families were given these drugs as a The Infection Control Law in Ja- Tetsuro Noda, prophylactic measure. -

Notice of Sale of Sakai Display Products Corporation Shares

[Translation based on material released on Tokyo Stock Exchange by Sharp Corporation] February 25, 2021 Company Name: Sharp Corporation Representative: J.W. Tai Chairman & Chief Executive Officer (Code No. 6753) Notice of Sale of Sakai Display Products Corporation Shares Sharp Corporation (“the Company”) has announced the decision made at a meeting of the Board of Directors convened today on the sale of its owned shares of Sakai Display Products Corporation (“SDP”) (“the Sale”). 1. Purpose of the Sale The Company received a proposal from the assignee to purchase SDP shares owned by the Company. After considerations, the Company has decided on the Sale based on the following: (1) As the Company aims to become a strong brand company, for devices businesses, the Company is promoting structural reform under the policy of aggressively collaborating with outer companies while securing core technology and maintaining stable procurement. Also for displays business, the Company has an accumulation of world-class technology and expertise within itself, and while maintaining collaboration and partnership relationship with SDP in intellectual property rights areas, the Company determined capital relationship with SDP is not mandatory for its business development. (2) The Company has an agreement with SDP to receive stable supply of high quality LCD panels even after capital relationship is dissolved. (3) By dissolving capital relationship, highly volatile large-size LCD business that requires continuous large investment to maintain competitiveness will be spun out, which is considered to contribute to stabilizing the Company’s consolidated business results. 2. Summary of the Sale (1) Number of owned shares before sale: 1,030,800 common shares (24.55% voting rights) (2) Number and amount of shares for sale: 1,030,800 common shares* *Sale price is non-disclosed based on duty of confidentiality with the assignee. -

PORTS of OSAKA PREFECTURE

Port and Harbor Bureau, Osaka Prefectural Government PORTS of OSAKA PREFECTURE Department of General Affairs / Department of Project Management 6-1 Nagisa-cho, Izumiotsu City 595-0055 (Sakai-Semboku Port Service Center Bldg. 10F) TEL: 0725-21-1411 FAX: 0725-21-7259 Department of Planning 3-2-12 Otemae, Chuo-ku, Osaka 540-8570(Annex 7th floor) TEL: 06-6941-0351 (Osaka Prefectural Government) FAX: 06-6941-0609 Produced in cooperation with: Osaka Prefecture Port and Harbor Association, Sakai-Semboku Port Promotion Council, Hannan Port Promotion Council Osaka Prefectural Port Promotion Website: http://www.osakaprefports.jp/english/ Port of Sakai-Semboku Japan’s Gateway to the World. With the tremendous potential and vitality that befit the truly international city of Osaka, Port of Hannan Seeking to become a new hub for the international exchange of people, From the World to Osaka, from Osaka to the Future goods and information. Starting from The sea is our gateway to the world – The sea teaches us that we are part of the world. Port of Nishiki Port of Izumisano Osaka Bay – Japan’s marine gateway to the world – is now undergoing numerous leading projects that Osaka Bay, will contribute to the future development of Japan, including Kansai International Airport Expansion and the Phoenix Project. Exchange for Eight prefectural ports of various sizes, including the Port of Sakai-Semboku (specially designated Port of Ozaki Port of Tannowa major port) and the Port of Hannan (major port), are located along the 70 kilometers of coastline the 21st Century extending from the Yamato River in the north to the Osaka-Wakayama prefectural border in the south. -

Voting Patterns of Osaka Prefecture

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1974 The Post-War Democratization of Japan: Voting Patterns of Osaka Prefecture Hiroyuki Hamada College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Hamada, Hiroyuki, "The Post-War Democratization of Japan: Voting Patterns of Osaka Prefecture" (1974). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624882. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-yyex-rq19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POST-WAR DEMOCRATIZATION OF JAPAN: n VOTING PATTERNS OF OSAKA PREFECTURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts by Hiroyuki Hamada May, 197^ APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved: May, 197^ Edwin H. Rh: Satoshi Ito, Ph.D. ___ Elaine M. The mo ^ Ph.D. DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my father, Kazuo Hamada, OSAKA, Japan. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............... iv LIST OF TABLES ............... v LIST OF MAPS AND GRAPH .......... ....... vii ABSTRACT . ......... viii INTRODUCTION ...................... .......... 2 CHAPTER I. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

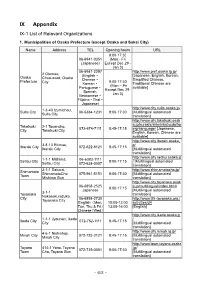

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations 1. Municipalities of Osaka Prefecture (except Osaka and Sakai City) Name Address TEL Opening hours URL 9:00-17:30 06-6941-0351 (Mon - Fri (Japanese) Except Dec 29 - Jan 3) 06-6941-2297 http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/ 2 Otemae, (English・ [Japanese, English, Korean, Osaka Chuo-ward, Osaka Chinese・ Simplified Chinese, Prefecture 9:00-17:30 City Korean・ Traditional Chinese are (Mon – Fri Portuguese・ available] Except Dec 29- Spanish, Jan 3) Vietnamese・ Filipino・Thai・ Japanese) http://www.city.suita.osaka.jp/ 1-3-40 Izumichou, Suita City 06-6384-1231 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Suita City translation] http://www.city.takatsuki.osak a.jp/kurashi/shiminkatsudo/for Takatsuki 2-1 Touencho, 072-674-7111 8:45-17:15 eignlanguage/ [Japanese, City Takatsuki City English, Korean, Chinese are available] http://www.city.ibaraki.osaka.j 3-8-13 Ekimae, p/ Ibaraki City 072-622-8121 8:45-17:15 Ibaraki City [Multilingual automated translation] http://www.city.settsu.osaka.jp 1-1-1 Mishima, 06-6383-1111 Settsu City 9:00-17:15 / [Multilingual automated Settsu City 072-638-0007 translation] 2-1-1 Sakurai, http://www.shimamotocho.jp/ Shimamoto ShimamotoCho 075-961-5151 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Town Mishima Gun translation] http://www.city.toyonaka.osak 06-6858-2525 a.jp/multilingual/index.html/ 9:00-17:15 Japanese [Multilingual automated 3-1-1 Toyonaka translation] Nakasakurazuka, City 06-6858-2730 http://www.tifa-toyonaka.org./ Toyonaka City English(Mon, 10:00-12:00 activities/34 Tue, Thu & Fri) 13:00-16:00 -

Guidebook for Business Investment in Sakai

Industry-support institutions provide: Finely tuned business support and incubation services Fully Supporting SMEs ! Sakai City Industrial Promotion Center ■ Business Matching Service A business matching service is provided based on the information on products and technologies collected from visits to companies in the city. Our business matching coordinators with specialized knowledge help identify potential business partners from among more than 1,300 local small- and medium-sized manufacturers. Linking Companies with Sakai City ■ Support Program for Industry-University Collaboration/Technological Development Dedicated coordinators provide a matching service to commercialize the research seeds of universities and public research institutes or to solve issues in developing Guidebook for Business new products/technologies. ■ Support Center for Introducing IPC Smart Manufacturing The Center supports companies considering introducing IoT, AI, or robots to improve Investment in Sakai productivity, create high value-added products and technologies, or address personnel deficiencies. ■ Development of Human Resources for Business We support human resources development by holding various kinds of seminars and training for those engaged in manufacturing. They include seminars for current and future business owners who are expected to play a leading role in bringing innovation and a competitive edge to the industry. Contact Financial Support Division, Sakai City Industrial Promotion Center 183-5 Access the website from here. Nagasone-cho, Kita-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 591-8025 TEL:+81 (0)72 255 6700 FAX:+81 (0)72 255 1185 URL:https://www.sakai-ipc.jp/ Basis for Business Incubation in Sakai for Future Hope and Challenge Sakai Business Incubation Center (S-Cube) The Center rents office or laboratory space to entrepreneurs who plan to start new businesses or develop new products and technologies, and provides free and comprehensive management support from incorporation to commercialization in accordance with the individual needs of each tenant. -

Werner, Griffin Bryce, M.A. May 2020 Philosophy Nishitani Keiji's Solution

Werner, Griffin Bryce, M.A. May 2020 Philosophy Nishitani Keiji’s Solution to the Problem of Nihilism: The Way to Emptiness (63 pg.) Thesis Advisor: Jung-Yeup Kim In Religion and Nothingness, Nishitani Keiji offers a diagnosis and solution to the problem of nihilism in Japanese consciousness. In order to overcome the problem of nihilism, Nishitani argues that one needs to pass from the field of consciousness through the field of nihility to the field of emptiness. Drawing upon Japanese Buddhist and Western philosophical sources, Nishitani presents an erudite theoretical resolution to the problem. However, other than Zen meditation, Nishitani does not provide a practical means to arrive on the field of emptiness. Since emptiness must be continuously emptied of conceptual representations for it to be fully experienced, I argue that solving the problem of nihilism in Japanese consciousness requires individuals first become aware of the reality of the problem of nihilism in Nishitani’s terms and then personally contend with emptying representations of emptiness in their own lives. Nishitani Keiji’s Solution to the Problem of Nihilism: The Way to Emptiness A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Griffin Bryce Werner May 2020 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Griffin Bryce Werner B.S., Villanova University, 2017 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by Jung-Yeup Kim , Advisor Michael Byron , Chair, Department of Philosophy James L. Blank , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………………iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………...v INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTERS I. -

The Sakai Kango Toshi (Moat City) Site

The Sakai Kango Toshi (Moat city) Site What is the Sakai Kango Toshi Site? Layers of burned ground indicate a big fire Sakai’s golden era ran from the latter half of the Muromachi period to the beginning of the Edo period. The town that prospered as a trading hub and self-governing city 400 years ago still exists beneath today’s streets. The Sakai Kango Toshi Site is very large at 3km from north to south, and 1km east to west. The site is surrounded by the Hanshin Expressway Sakai Line to the east, the Uchikawa River to the west and the Doigawa River to the south. While this site covers the town as it was plotted out by the Edo Shogunate after the big fire of the Osaka Summer Battle in 1615 (Keicho 20), excavations have found that the town there before the fire was slightly smaller. Many layers of scorched earth can be found beneath the surface. These are evidence of several big fires which occurred in Sakai. The scorched earth shows the rows of the houses and streets of those days. Many relics and ruins have been discovered there which show a level of prosperity in Sakai not reflected in the archives. In Sakai there were many wealthy merchants called Kaigoshu (Egoshu) or Nayashu merchants. Residences of Wealthy Merchants The site of a former large residence Sakai was ruled by a council made up of powerful merchants known as the kaigoshu and the nayashu, and these wealthy merchants who contributed to the prosperity of Sakai built large residences in the town. -

Hiding Between Basho and Chōra Re-Imagining and Re-Placing the Elemental

Research in Phenomenology 49 (2019) 335–361 Research in Phenomenology brill.com/rp Hiding Between Basho and Chōra Re-imagining and Re-placing the Elemental Brian Schroeder Rochester Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract This essay considers the relation between two fundamentally different notions of place—the Greek concept of χώρα and the Japanese concept of basho 場所—in an effort to address the question of a possible “other beginning” to philosophy by re- thinking the relation between nature and the elemental. Taking up a cross-cultural comparative approach, ancient through contemporary Eastern and Western sources are considered. Central to this endeavor is reflection on the concept of the between through an engagement between, on the one hand, Plato, Martin Heidegger, Jacques Derrida, Edward Casey, and John Sallis, and on the other, Eihei Dōgen, Nishida Kitarō, and Watsuji Tetsurō. Keywords elemental – nature – place – Greek Philosophy – Kyoto School – Zen Buddhism “Nature loves to hide” (Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεί), Heracleitus of Ephesus is fa- mously credited with having said.1 But where does nature hide? In what place or space? Has it always hid from the beginning? Or is the beginning the event of the hiding? Nature and the elemental are inextricably connected. And the question of the elemental is bound to the question of the beginning. Does 1 See John Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2003), 134; Milton Nahm, Selections from Early Greek Philosophy, 4th ed. (New York: Appleton- Century-Crofts, 1964), 68; Philip Wheelwright, ed., The Presocratics (New York: The Odyssey Press, Inc., 1966), 70. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/15691640-12341430 336 Schroeder nature hide behind the elemental? Or is the elemental the open hiding place of nature? Western philosophy’s home-ground is ancient Greece, but this particu- lar beginning is no longer sufficient in itself. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 335 B 23732 ARIDA 0 0 0 48 48 District 335 B 23733 DAITO 0 0 0 46 46 District 335 B 23734 FUJIIDERA 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23735 HIGASHI OSAKA FUSE 0 0 3 30 33 District 335 B 23736 HIGASHI OSAKA CHUO 0 0 0 21 21 District 335 B 23737 HIGASHI OSAKA KIKUSUI 0 0 0 38 38 District 335 B 23738 GOBO 0 0 0 51 51 District 335 B 23739 HABIKINO 0 0 0 42 42 District 335 B 23740 HASHIMOTO 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23741 HIGASHI OSAKA APOLLO 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23742 HIRAKATA 0 0 0 73 73 District 335 B 23743 HIGASHI OSAKA 0 0 1 38 39 District 335 B 23744 IBARAKI 0 0 0 92 92 District 335 B 23745 IKEDA 0 0 0 55 55 District 335 B 23746 ITO KOYASAN L C 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23747 IZUMIOSAKA 0 0 0 27 27 District 335 B 23748 IZUMI OTSU 0 0 0 69 69 District 335 B 23749 IZUMISANO 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23750 IZUMISANO CHUO 0 0 0 35 35 District 335 B 23751 KADOMA 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23752 KAINAN 0 0 0 30 30 District 335 B 23753 KAIZUKA 0 0 0 34 34 District 335 B 23754 KAWACHINAGANO 1 0 2 34 36 District 335 B 23755 HIGASHI OSAKA KAWACHI 0 0 2 25 27 District 335 B 23756 KASHIWARA 0 0 0 68 68 District 335 B 23758 KATSUURA 0 0 0 23 23 District 335 B 23759 KISHIWADA CHIKIRI 0 0 0 44 44 District 335 B 23760 KISHIWADA 0 0 0 45 45 District 335 B 23761 KISHIWADA CHUO 0 0 2 55 57 District 335 B 23763 KONGO 1 1 0 28 28 District 335 B 23764 KUSHIMOTO 0 0 2 24