Viagra Vs Cilias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel from Airports to Central London and Laban

SUMMER SCHOOL 2014 Information Pack SUMMER SCHOOL 2015 INFORMATION PACK Page | 1 SUMMER SCHOOL 2015 INFORMATION PACK Dear Course Participant, Welcome to Trinity Laban’s Summer School! The following information should provide you with everything you need to know concerning the course this summer. Summer School is a great chance to be fully immersed in dance and movement for a busy fortnight with us. We hope the course will be a rich and inspiring experience for you. Alongside the daily classes, you will be able to find out about full-time training, look after your body through additional health and well-being activities, and watch free programmed performances as well as making new friends, socialising and relaxing! The course attracts an international community from all around the world, and we’re always excited to see people from many different dance backgrounds. We aim to make you feel as welcome and supported as possible! Should you have any questions prior to the start of the course, please do not hesitate to contact Rebecca Wyatt, Programme Administrator on 020 8305 9477, or [email protected] We hope that you have a great time with us this summer and look forward to warmly welcoming you! Best Wishes Veronica Jobbins Head of Learning and Participation (Dance) Page | 2 CONTENTS 1. About Laban 2. Finding the Laban Building 3. Arriving in London: Travelling to Laban from London Airports 4. Local Shops and Services 5. Accommodation 6. Course Structure 7. Talks, Workshops and Other Fun Things! 8. Performances 9. Laban Health Price List 10. -

Canary Wharf –Dlr Station 15 Colonnade, Canary Wharf

SHOP TO LET CANARY WHARF –DLR STATION 15 COLONNADE, CANARY WHARF LOCATION Canary Wharf is an area that continues to develop. The Canary Wharf Estate now includes over 1.5m sqm of retail and office space. This covers Canada Water, Cabot Square and Westferry Circus, together with West India Quay and Woof Wharf. Canary Wharf includes the Docklands Light Railway Station. The station was built into the base of One Canada Square itself, between two parts of a Shopping Centre, and serves the Canary Wharf office complex. The station itself has six platforms serving three rail tracks and is sheltered by a glass roof. The DLR station is a short walk from Canary Wharf underground station and Heron Quays DLR Station. The subject premises is situated in the DLR station at the Accommodation bottom of the escalator, in a prime position. Located Total Area 1,025 sq ft 95.3 sq m opposite to Paddy Power, and adjacent to Starbucks and DESCRIPTION Tortilla. There is a small storage unit located outside of Business Rates the DLR station on South Colonnade, which is approximately 70 sq. ft. Rateable Value £110,000 Rates Payable £54,120 The unit is available by way of a new lease for a term of LEASE years, contracted outside of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. Service Charge There is a small service charge The landlord is seeking offers in the region of £195,000 payable to The Canary Wharf Group – per annum net of VAT or a percentage of turnover, Figure TBC RENT whichever is the higher and will be exclusive of rates and service charge. -

Mckenzie Ultimate Guide: Passrider Series

MUG: Passrider Series - London, England Hotels McKenzie Ultimate Guides: Passrider Series - London, England Hotels By Kerwin McKenzie (Amazon Bestselling Author) © 2012 – MUG: Passrider Series |Page 1 MUG: Passrider Series - London, England Hotels Copyright Normal copyright laws are in effect for use of this document. You are allowed to make an unlimited number of verbatim copies of this document for individual personal use. This includes making electronic copies and creating paper copies. As this exception only applies to individual personal use, this means that you are not allowed to sell or distribute, for free or at a charge paper or electronic copies of this document. You are also not allowed to forward or distribute copies of this document to anyone electronically or in paper form. Mass production of paper or electronic copies and distribution of these copies is not allowed. © 2012 McKenzie Ultimate Guides All Rights Reserved © 2012 – MUG: Passrider Series |Page 2 MUG: Passrider Series - London, England Hotels Acknowledgements Thanks to the following friends who provided guidance, support and input. • Alexis Brathwaite • Nadia Karim • Joe DWR Martin • Lake Phalgoo • Lee Sample • Richard Sawyer • Sam Wiltzius © 2012 – MUG: Passrider Series |Page 3 MUG: Passrider Series - London, England Hotels About the Author I’m a commercial aviation enthusiast and a global traveler living in the United States. I’ve worked in the airline industry for 16.5 years and hold a Masters degree in Aeronautical Sciences from Embry- Riddle Aeronautical University known as the “Harvard of the Skies.” In addition, I’ve also visited over 105 countries and counting and flown countless airlines and aircraft types. -

PDU Case Report XXXX/Yydate

planning report PDU/2187a&2188a/02 13 May 2009 City Pride and Island Point, Westferry Road in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets planning application no. PA/08/02292/3 Strategic planning application stage II referral (new powers) Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 The proposal City Pride – The erection of a part 9, part 62-storey tower comprising 430 residential units, 203- bed hotel with conference facilities, spa, swimming pool, gymnasium, reception and lounge bar. Island Point – The erection of six buildings ranging in height from 2 to 8 storeys comprising 189 residential units. The applicant The applicant is Glenkerrin Ltd, and the architect is Fosters and Partners and Darling Associates. Strategic issues The principle of the redevelopment of both sites to provide residential led developments is in the interest of good strategic planning in London. Further clarification and information has been provided regarding affordable housing, child play space, climate change mitigation and transport. On the basis of this information the applications are consistent with London Plan policy. Recommendation That Tower Hamlets Council be advised that the Mayor is content for it to determine the case itself, subject to any action that the Secretary of State may take, and does not therefore wish to direct refusal or direct that he is to be the local planning authority. Context 1 On 11 November 2008 the Mayor of London received documents from Tower Hamlets Council notifying him of a planning application of potential strategic importance to develop the above site for the above uses. -

Finding 25 Churchill Place from London Bridge Station (Jubilee Line)

Finding 25 Churchill Place From London Bridge Station (Jubilee Line) Go to the Jubilee Line Platform for East-bound trains. As you enter the platform, turn right and make your way nearly to the end of the platform to wait for the next train. Exit the train at Canary Wharf and go up either the first or second escalators, which will display signs for Upper Bank Street and Montgomery Street, then make your way through the barriers. Turn right after the barriers and go through the doors marked Canada Square & Churchill offices & shops. Head up the escalator. Keep straight ahead when you reach the top, following the signs to Churchill Place. Head through the hallway, turn left at the end and head up the escalator. At the top, turn right and travel across the waterway through the glass hallway. Exit the hallway using the first doors on the left, before the escalator – disregard the fact it looks like a fire exit. As you exit, 25 Churchill Place is the building on your right. Make your way around the corner to the right – pass 30 Churchill Place (entrance to the European Medical Agency) – and use the next entrance. You have arrived. From Canary Wharf DLR Station Exit the DLR at Canary Wharf. Head down the stairs directly from the platform – do not enter the shopping centre. Exit the station to the South without entering the shopping centre. Cross the street (South Colonnade) and turn left (East). Follow this street all the way to Churchill Place – you’ll pass Wahaca and Waitrose on your left. -

2012 Olympic Visitor Mooring Locations London

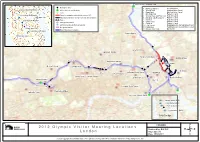

( ( ! ! River Lee A104 Lea Bridge Road Ø (!Ø Mooring locations 1 Hackney Marshes Lee Navigation Canary Wharf DLR Station (! Likely extents of controlled zone 2 Victoria Park Hertford Union Canal (!Ø Locks 3 Bow Wharf Hertford Union Canal 4 Mile End Park Regent's Canal Heron Quays DLR Station Subject to navigation restrictions in summer 2012 5 Victoria Park, Old Ford Lock Regent's Canal (!Ø West India Lock Waterways around the Olympic Park closed to navigation 6 Islington, City Road Lock Regent's Canal 7 Islington Regent's Canal South Quay DLR Station Tunnels 8 King's Cross Regent's Canal Underground stations 9 Camden Regent's Canal 12 DLR (Docklands Light Railway) stations 10 Little Venice Paddington Arm (Grand Union Canal) "" Overground stations 11 Paddington Paddington Arm (Grand Union Canal) Millwall Inner Dock 12 Millwall Inner Dock Docklands British Waterways' navigations Crossharbour DLR Station Clapton Station Millwall Outer Dock 1 Homerton Station Highbury & Islington ( ! Hackney Wick Station Ø Stratford Station Ø Ø(!Ø !( ( ! ( 9 ØØ !( Ø ! Ø (! Haggerston Station !( Ø !(Ø (! Olympic Stadium ( (!Ø 8 !Ø 2 ! St John's Wood ( Ø Camden Town !(Ø 5 7 6 (!Ø 3 (!Ø West Ham (! Cambridge Heath Station Bow Road Ø Angel Hoxton Station 4 King's Cross St Pancras Station (!Ø ( (! ! Bromley by Bow Bethnal Green Ø Ø Warwick Avenue Mile End ( ! (! Ø Little Venice 11 Liverpool Street Station ( 10 ! Ø ( ! Paddington Station Ø (! ( ! Ladbroke Grove Ø Limehouse Lock Limehouse Station (DLR) (! Canary Wharf (DLR) Hero(!nØs Quays (DLR) South Quay (DLR) 12 Crossharbour (DLR) Inset map 1:50,000 2 0 1 2 O l y m p i c V i s i t o r M o o r i n g L o c a t i o n s Produced by: BW GIS L o n d o n Page size: A3 Date: 15/04/2011 - © Crown copyright and database rights, 2011, Ordnance Survey 100019843. -

PA/05/02114 Date Received: 22/12/2005 Last Amended Date: 22/12/2005 1.2 Application Details

Committee: Date: Classification: Report Agenda Item Development 8 March 2006 Unrestricted Number: Number: Committee DC039/056 5.1 Report of: Title: Town Planning Application Director of Development and Renewal Location: Cabot Hall, Cabot Square, London, E14 Case Officer: Scott Hudson Ward: Millwall (February 2002 onwards) 1. SUMMARY 1.1 Registration Details Reference No: PA/05/02114 Date Received: 22/12/2005 Last Amended Date: 22/12/2005 1.2 Application Details Existing Use: Conference Facility/Retail Mall/Car Park. Proposal: The change of use of Cabot Hall and Cabot Place West retail mall, as follows: • Gross total floor space of no more than 12,587sq.m. • Change of use of existing 2,541sq.m. D1 space (public hall), and 2,563sq.m. car park to Class A1 (shops). • Additional 939sq.m. of new Class A1 (shops) floor space . • Reconfiguration of 6,544sq.m existing retail to Class A1 (shops) and Class A3/A4/A5 (café, restaurant, bar and take-aways). • Ancillary storage and mall circulation spaces. • Associated minor external works to western elevation. Applicant: DP9 Planning Consultants Ownership: Cabot Place Ltd. Historic Building: N/A Conservation Area: N/A 2. RECOMMENDATION: 2.1 That the Development Committee grant planning permission subject to: i) the conditions outlined below: (1) Time limit for commencement (three years) (2) Restriction within approved use classes (Class A3/A4/A5, up to a maximum 3,000sq.m). (3) Refuse and recycling facilities (4) External Materials and Finishes to match existing. (5) No structures on roof. (6) Disabled Access (Retention) (7) Commercial parking retained for businesses/visitors. -

Our Ref: MGLA260419-1320 24 May 2019 Dear Thank You for Your

(By email) Our Ref: MGLA260419-1320 24 May 2019 Dear Thank you for your request for information which the GLA received on 25 April 2019. Your request has been dealt with under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. You asked for; I’m seeking copies of correspondence sent or received by members of the mayoral team in relation to the recent climate change protests by the activist group Extinction Rebellion. Please provide: • Copies of all relevant emails sent or received by Sadiq Khan between 14 April 2019 and 25 April 2019. • Copies of all relevant emails sent or received by Shirley Rodrigues between 14 April 2019 and 25 April 2019. To help you locate the relevant correspondence, please search these email accounts for messages sent or received between the specified dates and containing the keywords “Extinction Rebellion”, “climate”, “protest” or “protests”. Please find attached information. Please note that the emails we have located within scope of your request relating to the Mayor are from members of the public and third parties. Some of the information is therefore exempt from disclosure under s.40 (Personal information) of the Freedom of Information Act. This information could potentially identify specific employees or members of the public and as such constitutes as personal data which is defined by Article 4(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable living individual. It is considered that disclosure of this information would contravene the first data protection principle under Article 5(1) of GDPR which states that Personal data must be processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject. -

One Park Drive Canary Wharf, London 1

One Park Drive Canary Wharf, London 1 One Park Drive, Canary Wharf, London The new residential district of Canary Wharf will be one of green garden spaces, riverside boardwalks and luxury waterfront living. The area is due to house 3,300 new homes, a school, parks and more. One Park Drive will be the signature building in this new destination located in the very heart of Canary Wharf, a vibrant, well-connected office, retail and nightlife area. The new district will be located just to the One Park Drive will begin as a freestanding east of the existing Canary Wharf Estate. landmark and is nothing short of an The expansion includes the redevelopment architectural triumph, designed by of 9.39 hectares of current brownfield sites. world-renowned architects Herzog & de When complete, it will incorporate Meuron. Eventually, it will form part of the 3.6 hectares of public space and gardens, streets, parks and wider urban area of this 2.7 million square feet of residential space new district in Canary Wharf. featuring 3,300 new homes, 2 million square feet of new office space and It is a unique building, designed to work 380,000 square feet of retail. on a human scale. One Park Drive is a singular building made up of three distinct zones. Each zone has its own characteristics but they work together to create an inimitable building. The three zones allow a sense of individuality in the larger development. West India Quay DLR North Dock Crossrail Place Elizabeth Line CYCLE HIRE CANADA Blackwall Basin WESTFERRY CABOT DLR ONE CANADA CHURCHILL CARTIER SQUARE SQUARE SQUARE PLACE CIRCLE CIRCUS Canary Wharf PARK DLR WOOD WHARF QUAY LOVEGROVE WALK BERNIERS Canary Wharf Canary Wharf PLACE Pier Jubilee Line Middle Dock UNION SQ. -

Your Pathway to a Great British University Foundation, Undergraduate Year 1 and Pre-Masters Programmes Contents

Your pathway to a great British university Foundation, Undergraduate Year 1 and Pre-Masters programmes Contents 1 Realise your ambition: achieve outstanding results at Bellerbys College 2 Expert teachers help our students progress to some of the best universities 4 The Bellerbys Way 6 Scholarship Programme 8 Studying in the UK 10 Foundation programme 14 Foundation modules 19 Extended Foundation 20 Foundation university destinations Bellerbys College has a high 22 Undergraduate Year 1 reputation in my country and 24 Undergraduate Year 1 university destinations London is my favourite city in 26 Undergraduate Year 1 progression options the world. Universities seem to 28 Pre-Masters programme be delighted with enrichment activities that students are 30 IELTS Express doing. Being a part of the 31 Preparation courses enrichment activities makes my 32 Bellerbys Summer personal statement stronger 34 Four centres of excellence - four fantastic cities and more competitive. 36 Bellerbys College Brighton: A modern, British boarding school Billy from Hong Kong studied for 13 to 18 year-olds A Levels and achieved AAAC. 38 Welcome to Brighton: The UK’s most exciting city-by-the-sea Now studying Actuarial Science 40 Bellerbys College Cambridge: Our college for science and engineering at Cass Business School, City University London. 42 Welcome to Cambridge: The home of science and engineering 44 Bellerbys College London: Our college for business 46 Welcome to London: The world’s greatest business capital 48 Bellerbys College Oxford: Our college for arts, -

Digital Display Standards

Transport for London Digital display standards Issue 3 Contents Foreword 1 Basic elements 2 Basic rules of layout 3 Transitions and animations 4 Information on multiple screens 5 Digital display examples For further information Foreword Digital display standards have been produced to ensure consistency across all of TfL’s digital displays. They are designed to ensure consistency of spacing, size of font, use of colour etc. The standards also help to ensure that information is displayed in a modular nature. The standards do not specify the type of hardware or software to be used. ‘Digital displays’ are defined in this document as electronic screens that convey TfL controlled information to customers via live feeds. Such displays may be in stations, on vehicle or on street. These standards do not apply to websites or dot matrix indicators. For guidance on implementing the rules within these standards please email [email protected] 1 Basic elements This section provides guidance on the basic elements that make up the TfL digital display standards. Further information on TfL graphic standards can be found at tfl.gov.uk/corporatedesign. Central line Circle line District line 1.1 The grid All TfL digital displays must work to a grid, as shown. A grid is used to ensure that a transferable unit of measurement is available for all screen sizes and aspect ratios. A grid should adapt to any screen size or aspect ratio. 1.2 Screen aspect ratios Shown here are examples of common 4:3 screen aspect ratios. Note that aspect ratios (as well as screen dimensions) will vary in size. -

Development Committee ______

Meeting of the DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE ________________________________________________ Wednesday, 29 March 2006 at 7.30 p.m. ______________________________________ A G E N D A __________________________________________ VENUE Council Chamber, 1st Floor, Town Hall, Mulberry Place, 5 Clove Crescent, London, E14 2BG Members: Deputies (if any): Chair: Councillor Rofique U Ahmed Vice-Chair:Councillor Julian Sharpe Councillor Ray Gipson Councillor Janet Ludlow, (Designated Councillor Julia Mainwaring Deputy for Councillors Martin Rew, Akikur Councillor Ashton McGregor Rahman & Ray Gipson) Councillor Muhammed Ghulam Mortuza Councillor James Sanderson, (Designated Councillor Akikur Rahman Deputy for Councillors Martin Rew, Akikur Councillor Martin Rew Rahman & Ray Gipson) Councillor Salim Ullah Councillor Azizur Rahman Khan, (Designated Deputy for Councillors Martin Rew, Akikur Rahman & Ray Gipson) [Note: The quorum for this body is 4 Members]. If you require any further information relating to this meeting, would like to request a large print, Braille or audio version of this document, or would like to discuss access arrangements or any other special requirements, please contact: Louise Fleming, Democratic Services, Tel: 020 7364 4878, E-mail:[email protected] LONDON BOROUGH OF TOWER HAMLETS DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Wednesday, 29 March 2006 7.30 p.m. 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE To receive any apologies for absence. 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To note any declarations of interest made by Members, including those restricting Members from voting on the questions detailed in Section 106 of the Local Government Finance Act, 1992. Note from the Chief Executive In accordance with the Council’s Code of Conduct, Members must declare any personal interests they have in any item on the agenda or as they arise during the course of the meeting.