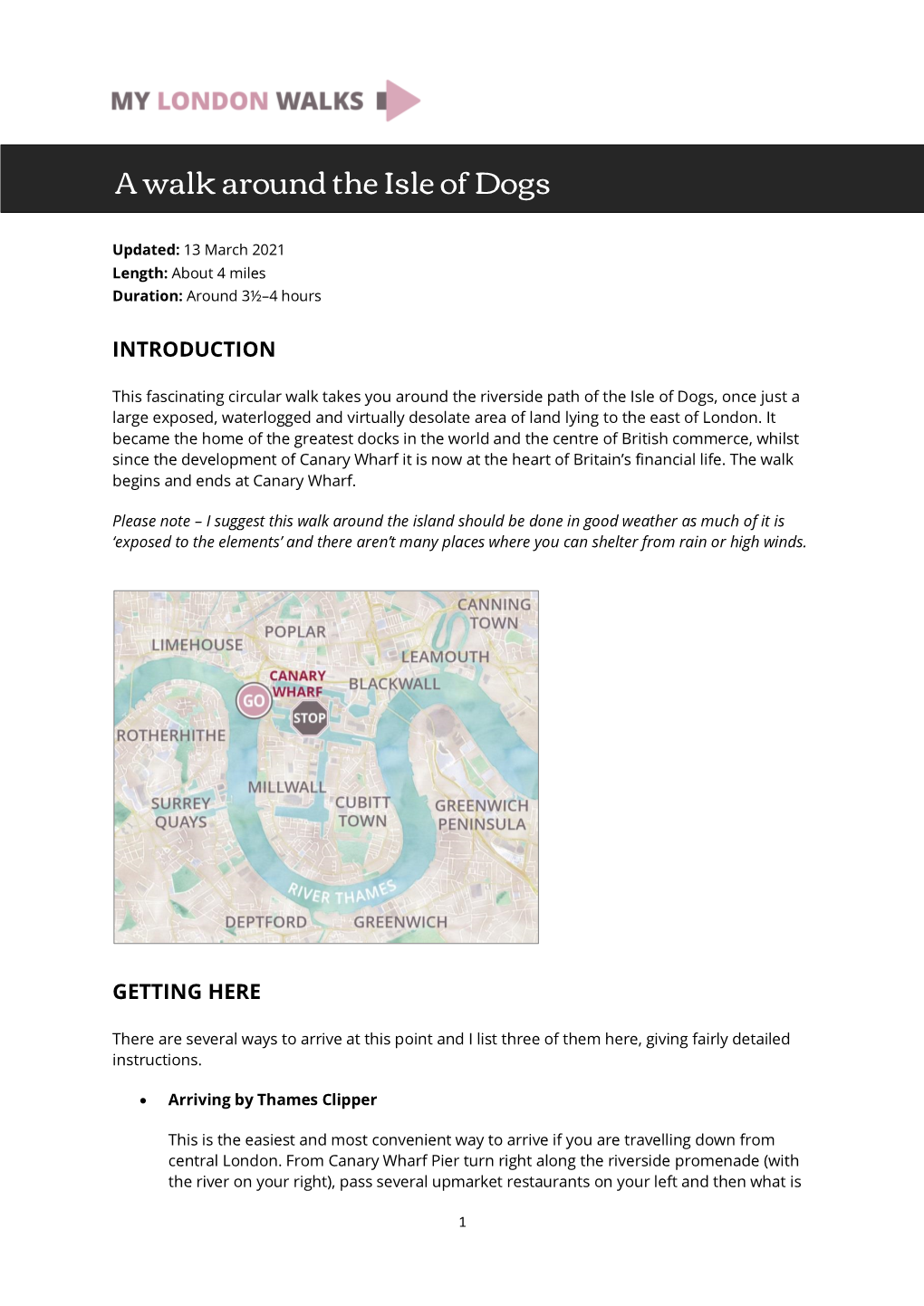

A Walk Around the Isle of Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty and Philanthropy in the East

KATHARINE MARIE BRADLEY POVERTY AND PHILANTHROPY IN EAST LONDON 1918 – 1959: THE UNIVERSITY SETTLEMENTS AND THE URBAN WORKING CLASSES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD IN HISTORY CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between the university settlements and the East London communities through an analysis their key areas of work during the period: healthcare, youth work, juvenile courts, adult education and the arts. The university settlements, which brought young graduates to live and work in impoverished areas, had a fundamental influence of the development of the welfare state. This occurred through their alumni going on to enter the Civil Service and politics, and through the settlements’ ability to powerfully convey the practical experience of voluntary work in the East End to policy makers. The period 1918 – 1959 marks a significant phase in this relationship, with the economic depression, the Second World War and formative welfare state having a significant impact upon the settlements and the communities around them. This thesis draws together the history of these charities with an exploration of the complex networking relationships between local and national politicians, philanthropists, social researchers and the voluntary sector in the period. This thesis argues that work on the ground, an influential dissemination network and the settlements’ experience of both enabled them to influence the formation of national social policy in the period. -

Treasury Management Practices (Tmps)

Appendix 2 Treasury Management Practices Version 1.0 Approved By: Audit Committee Number Issue Date March 2021 1 TREASURY MANGEMENT PRACTICES PRINCIPLE AND SCHEDULES This document has been prepared in the sequence provided by CIPFA. For ease of use, the key areas for North Lincolnshire Council treasury operations are referenced below: TMP Number Page Organisational chart of the Council’s Finance and TMP 5 17 Treasury Division Statement of duties and responsibilities TMP 5 Absence cover TMP 5 Liquidity Management, Cash flow, bank overdraft, TMP 1.2 4 short-term borrowing/lending Cash flow forecasts TMP 8 24 Bank statements, payment scheduling TMP 3 12 Electronic banking and dealing TMP 5 17 Standard Settlement Instructions, Payment TMP 11 26 Authorisation Approved types and sources of borrowing TMP 4 14 Approved investment instruments TMP 4 Counterparty and Credit Risk Management TMP 1.1 3 Current criteria TMP 1.1 Electronic Banking and Dealing: TMP 5 17 Authorised dealers Dealing limits Settlement transmission procedures TMP 5.8 19-20 Reporting arrangements/Performance measurement TMP 6 21 Officers’ responsibilities for reporting TMP 2 10 TMP 5 17 Budget, Statement of Accounts, treasury-related TMP 7 23 information requirements for Auditors Anti Money Laundering Procedures TMP 9 24 Contingency Arrangements TMP 1.7 7 External Service Providers TMP 11 26 References to Statute and Legislation TMP 1.6 6 2 TMP1 - Risk Management 1. Credit and Counterparty Policies 1.1.1 All treasury management activities present risk exposure for the Council. The council’s policies and practices emphasise that the effective identification, management and containment of risk are the prime objectives of treasury management activities. -

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Hot 100 2016 Winners in London’S Residential Market CBRE Residential 2–3 Hot 100 2016

CBRE Hot 100 2016 winners in London’s residential market CBRE Residential 2–3 Hot 100 2016 The year is drawing to a close and so our annual Hot 100 report is published. Find out where was hot in 2016. Contents Best performing locations 4–5 Most affordable boroughs 8–9 For nature lovers 10–11 For shopaholics 14–15 Boroughs for renters 16–17 Best school provision 20–21 Tallest towers 22–23 Highest level of development 24–25 Demographic trends 28–29 Best economic performance 30–31 CBRE Residential 4–5 Hot 100 2016 Top 10 Best performing locations Although prices remain highest in Central London, with homes in Kensington and Chelsea averaging £1.35 million, the other London boroughs continue to see the highest rate of growth. For the second year running Newham tops the table for price growth. This year prices in Newham increased by 24%; up from 16% last year. The areas characterised by significant regeneration, such as Croydon and Barking and Dagenham, are recording price rises of 18% and 17%, which is well above the average rate of 12%. Top Ten Price growth Top Ten Highest value 1 Newham 23.7% 1 Kensington and Chelsea £1,335,389 2 Havering 19.0% 2 City of Westminster £964,807 3 Waltham Forest 18.9% 3 City of London £863,829 4 Croydon 18.0% 4 Camden £797,901 5 Redbridge 18.0% 5 Ham. and Fulham £795,215 6 Bexley 17.2% 6 Richmond upon Thames £686,168 7 Barking and Dagenham 17.1% 7 Islington £676,178 8 Lewisham 16.7% 8 Wandsworth £624,212 9 Hillingdon 16.5% 9 Hackney £567,230 10 Sutton 16.5% 10 Haringey £545,025 360 Barking CBRE Residential 6–7 Hot 100 2016 CBRE Residential 8–9 Hot 100 2016 Top 10 Most affordable boroughs Using a simple ratio of house prices to earnings we can illustrate the most affordable boroughs. -

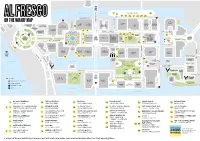

On the Wharf

W W HERTSMERE ROAD ROAD HERTSMERE E E S S T T F F E E R R DLR R R Y Y R R WEST O O INDIA A A QUAY D D NORTH DOCK NORTH DOCK 17 CROSSRAIL PLACE 25 ONTARIO WAY 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 ADAMS PLAZA BRIDGE ADAMS FISHERMAN'S WALK 17 COLUMBUS COURTYARD ONE ON THE WHARF MAP PASSAGE FROBISHER CHURCHILL 5 CANADA PLACE 10 CABOT 5 NORTH SQUARE 15 CANADA 30 NORTH 1 WESTFERRY COLUMBUS SQUARE COLONNADE 25 NORTH 8 CANADA SQUARE COLONNADE CIRCUS COURTYARD ONE 10 COLONNADE SQUARE CABOT SQUARE WREN LANDING 7 WESTFERRY CIRCUS 20 COLUMBUS COURTYARD 4 8 11 WESTFERRY CABOT SQUARE NORTH COLONNADE NORTH COLONNADE CIRCUS 9 28 29 27 26 THE IVY IN THE PARK 16-19 CANADA 32 1 5 SQUARE ONE DLR THE CANADA WAITROSE & CARTIER WESTFERRY CABOT PLACE CABOT PLACE CANADA PARK 31 SQUARE 34 PARTNERS CHURCHILL 2 CANARY SQUARE PAVILION PARK THIRD SPACE PLACE CIRCLE CIRCUS WHARF CHURCHILL PLACE WEST INDIA AVENUE PLATEAU 33 3 7 6 30 35 15 WESTFERRY ONE WEST CABOT SQUARE SOUTH COLONNADE UPPER BANK STREET SOUTH COLONNADE CIRCUS INDIA AVENUE FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 15 CUBITT STREET CHARTER STEPS NASH COURT 37 25 CABOT 20 CABOT 10 SOUTH 30 SOUTH 20 CANADA 25/30 SQUARE SQUARE COLONNADE COLONNADE 33 CANADA 25 CANADA SQUARE CHURCHILL 11 SQUARE SQUARE PLACE CANARY W WHARF E S PIER T F W 12 13 BERNERS PLACE E R E 16 38 R S Y T F STREET MONTGOMERY 15 WATER 30 HARBORD R E JUBILEE 36 OFFICE O R PLAZA MARKETING 1 WATER STREET SQUARE A R D Y 640 SUITE STREET MIDDLE DOCK RIVER THAMES R EAST O NEWFOUNDLAND UNDERGROUND UNDERGROUND MONTGOMERY A WATER STREET D SQUARE 12 BANK JUBILEE PARK UNDERGROUND WATER -

Hospital List

HEALTH+ HOSPITAL LIST For members Hospital List. NHS = NHS hospitals with private facilities P = Psychiatric hospital. Access to these hospitals is only available if you have selected the Mental Health option on your plan SPECIALIST INCOME PROTECTION HEALTH+ HOSPITAL LIST Where can I get treatment? As a Health+ member, you have access to leading private facilities which provide quality medical care. You can choose from three different lists: Essential Includes hospitals from the largest hospital groups and NHS private patient units. Standard Extends the coverage of the Essential list to include independent hospitals and clinics. Extended Offers the widest choice and provides access to a greater number of London hospitals. If you already have a Health+ policy, please check your Policy Certificate to find out which hospital list you are covered on. Please note you are only eligible for treatment at hospitals on your chosen list. Hospital lists often change as hospitals and clinics are added or removed, so you should always check with us before arranging treatment on 0300 123 3253. 2 of 16 England Essential Standard Extended Bedfordshire BMI The Manor Hospital Bedford 3 3 3 Luton & Dunstable Hospital Luton NHS 3 3 3 Berkshire The Bridge Clinic Maidenhead 3 3 Spire Dunedin Hospital Reading 3 3 3 Royal Berkshire Hospital Reading NHS 3 3 3 Berkshire Independent Hospital Reading 3 3 3 Circle Reading Reading 3 3 Spire Thames Valley Hospital Slough 3 3 3 Wexham Park Hospital Slough NHS 3 3 3 Cardinal Clinic Slough P 3 3 3 BMI The Princess Margaret -

Virgin Money London Marathon

Count on us for race day support! Virgin Money London Marathon @guidedogsevents @guide_dogs_events @guidedogsevents #TeamGuideDogs Guide Dogs Cheer Point Our cheering point will be at Mile 12, at the junction of High Holborn Tooley Street, Jamaica Road Farringdon Road Kingsway City Aldgate East T Newgate Street ower Gateway Commercial Road and Tanner Street. St Paul’s Fleet Street Bishopsgate Aldgate Bank Regent Street venue W St Paul’s Commercial Road est India Doc Charing Cross Road Cathedral Mansion Shadwell Blackfriars House Fenchurch St 21 Leicester Square StrandTemple Monument Limehouse UpperThames Street Canon St Shaftesbury A 24 Tower Gateway e k Road Victoria Embankment e g Westferry g Lower T Tower Hill 22 East India d Narrow Street All Saints i 35 W d i r hames THE HIGHWAY Piccadilly aterloo Bridge r 14 B Street Poplar High Street B LD Circus FIE The Highway m Charing s MITH 20 r u ST S D i a EA LimehouseA i 23 Cross n O r 13 Piccadilly R f e Tower of Y Poplar l HALFWAY Shadwell R k 40 l R i London E F l c T e S Blackwall E West India a M n W ay Hungerford Bridge l Embankment n Aspen W u B Quay W Southwark Bridge T St James’s e 15 London Bridge hitehall h N Colo Southwark t Horse i nna 25 h de r e h S Colonnade London Bridge t 19 The Mall amford Street The Shard Tooley Street 20 Wapping o 30 Guards Road Guards St R Southwark ower Bridge Wapping T Blac Brunel Road Canary Waterloo 10 Wharf Heron Quays kwall T S O2 Arena ’ Preston alter Road Canary Wharf Finish Line d unnel a London Eye o Westminster R 18 Heron Quays Rotherhithe -

YPG2EL Newspaper

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO EAST LONDON East London places they don’t put in travel guides! Recipient of a Media Trust Community Voices award A BIG THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS This organisation has been awarded a Transformers grant, funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor and managed by ELBA Café Verde @ Riverside > The Mosaic, 45 Narrow Street, Limehouse, London E14 8DN > Fresh food, authentic Italian menu, nice surroundings – a good place to hang out, sit with an ice cream and watch the fountain. For the full review and travel information go to page 5. great places to visit in East London reviewed by the EY ETCH FO P UN K D C A JA T I E O H N Discover T B 9 teenagers who live there. In this guide you’ll find reviews, A C 9 K 9 1 I N E G C N YO I U E S travel information and photos of over 200 places to visit, NG PEOPL all within the five London 2012 Olympic boroughs. WWW.YPG2EL.ORG Young Persons Guide to East London 3 About the Project How to use the guide ind an East London that won’t be All sites are listed A-Z order. Each place entry in the travel guides. This guide begins with the areas of interest to which it F will take you to the places most relates: visited by East London teenagers, whether Arts and Culture, Beckton District Park South to eat, shop, play or just hang out. Hanging Out, Parks, clubs, sport, arts and music Great Views, venues, mosques, temples and churches, Sport, Let’s youth centres, markets, places of history Shop, Transport, and heritage are all here. -

Water Space Study (2017)

Tower Hamlets Water Space Study London Borough of Tower Hamlets Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Marina Projects September 2017 Project Title: Tower Hamlets Water Space Study Client: London Borough of Tower Hamlets Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1.0 08/05/2017 Tower Hamlets Water Emma Luke Philip Smith Philip Smith Space Study: Draft Natalie Collins 2.0 09/06/2017 Tower Hamlets Water Emma Luke Philip Smith Philip Smith Space Study: Second Natalie Collins Draft 3.0 18/08/2017 Tower Hamlets Water Emma Luke Philip Smith Philip Smith Space Study: Third Draft Natalie Collins 4.0 22/09/2017 Tower Hamlets Water Emma Luke Philip Smith Philip Smith Space Study: Final Report Natalie Collins Tower Hamlets Water Space Study London Borough of Tower Hamlets Council Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Marina Projects September 2017 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Edinburgh 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 London London NW1 1JD FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] Manchester Lancaster Contents 1 Introduction 1 Why are the Borough’s Water Spaces important? 1 Purpose of this Study 1 2 Key issues for Tower Hamlets’ water spaces 5 Context 5 National Policy 6 London-wide policy 6 Local policy 7 Tower Hamlets 8 Historic loss of -

On the Wharf

W W HERTSMERE ROAD ROAD HERTSMERE E E S S T T F F E E R R DLR R R Y Y R R WEST O O INDIA A A QUAY D D NORTH DOCK NORTH DOCK 16 CROSSRAIL PLACE 24 ONTARIO WAY 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 ADAMS PLAZA BRIDGE ADAMS FISHERMAN'S WALK 17 COLUMBUS COURTYARD ONE ON THE WHARF MAP PASSAGE FROBISHER CHURCHILL 5 CANADA PLACE 10 CABOT 5 NORTH SQUARE 15 CANADA 30 NORTH 1 WESTFERRY COLUMBUS SQUARE COLONNADE 25 NORTH 8 CANADA SQUARE COLONNADE CIRCUS COURTYARD ONE 10 COLONNADE SQUARE CABOT SQUARE WREN LANDING 7 WESTFERRY CIRCUS 20 COLUMBUS COURTYARD 4 8 11 WESTFERRY CABOT SQUARE NORTH COLONNADE NORTH COLONNADE CIRCUS 9 27 28 26 25 THE IVY IN THE PARK 16-19 CANADA 31 1 5 SQUARE ONE DLR THE CANADA WAITROSE & CARTIER WESTFERRY CABOT PLACE CABOT PLACE CANADA PARK 30 SQUARE 33 PARTNERS CHURCHILL 2 CANARY SQUARE PAVILION PARK THIRD SPACE PLACE CIRCLE CIRCUS WHARF CHURCHILL PLACE WEST INDIA AVENUE PLATEAU 32 3 7 6 29 34 15 WESTFERRY ONE WEST CABOT SQUARE SOUTH COLONNADE UPPER BANK STREET SOUTH COLONNADE CIRCUS INDIA AVENUE FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 15 CUBITT STREET CHARTER STEPS NASH COURT 36 25 CABOT 20 CABOT 10 SOUTH 30 SOUTH 20 CANADA 25/30 SQUARE SQUARE COLONNADE COLONNADE 33 CANADA 25 CANADA SQUARE CHURCHILL 11 SQUARE SQUARE PLACE CANARY W WHARF E S PIER T F W 12 13 BERNERS PLACE E R E 37 R S Y T F STREET MONTGOMERY 15 WATER 30 HARBORD R E JUBILEE 35 OFFICE O R PLAZA MARKETING 1 WATER STREET SQUARE A R D Y 640 SUITE STREET MIDDLE DOCK RIVER THAMES R EAST O NEWFOUNDLAND UNDERGROUND UNDERGROUND MONTGOMERY A WATER STREET D SQUARE 12 BANK JUBILEE PARK UNDERGROUND WATER STREET -

Five Churchill Place Canary Wharf a Landmark Building with an Impressive New Reception and Category a Floors

FIVE CHURCHILL PLACE CANARY WHARF A LANDMARK BUILDING WITH AN IMPRESSIVE NEW RECEPTION AND CATEGORY A FLOORS Five Churchill Place occupies a prominent position amongst the landmarks and world-class occupiers of Canary Wharf. The stunning entrance leads into a newly refurbished reception hall. The accommodation is arranged over the 10th and 11th floors providing 53,669 sq ft of new Category A offices. 01 | 02 FIVE CHURCHILL PLACE | THE BUILDING FIVE CHURCHILL PLACE | THE SPECIFICATION EXCEPTIONAL SPACE WITH A HIGH SPECIFICATION – Four pipe fan coil air-conditioning – 3 x 2,000 KVA building standby generators, providing back up for – Enhanced raised floor void of 200mm all business critical operations, – Enhanced floor to ceiling height of 2.8m with provision for a fourth set – 11 KV electrical service with dual power – 2 x goods lifts (3,000 + 1,800kg) from 2 different EDF substations – 1.5m planning grid – 1 x 1,000 KVA UPS providing N+1 – BREEAM rating of “Excellent” redundancy to floors 5-12 – Newly refurbished double height – 8 x 21 person (1,600 kg) passenger lifts reception with a natural stone finish 03 | 04 AMONGST PRESTIGIOUS NEIGHBOURS POPLAR NORTH QUAY WEST INDIA QUAY Existing Buildings NORTH DOCK CROSSRAIL STATION Future Developments 17 COLUMBUS 1 WESTFERRY CIRCUS COURTYARD ONE 15 CANADA 30 NORTH CHURCHILL HEALTH WESTFERRY ROAD 5 CANADA 8 CANADA SQUARE COLONNADE PLACE CLUB / 10 CABOT 5 NORTH 25 NORTH SQUARE SQUARE RESTAURANT SQUARE COLONNADE COLONNADE 7 WESTFERRY ONE CABOT SQUARE CIRCUS 20 COLUMBUS 5 COURTYARD NORTH COLONNADE -

Baltimore Tower

BALTIMORE TOWER CROSSHARBOUR LONDON E14 BALTIMORE TOWER An iconic new landmark for luxury living creating a new focus on Canary Wharf’s world famous skyline A JOINT DEVELOPMENT BY BALTIMORE TOWER Canary Wharf - a track record second to none BALTIMORE TOWER Canary Wharf is the hub of one of the most dynamic transport infrastructures in the world Residents at Baltimore Tower will connect within 2 minutes walk at Crossharbour connect from Crossharbour THE DLR JUBILEE LINE MAINLINE CROSSRAIL CABLE CAR THAMES RIVER BUS SOUTH QUAY HERON QUAYS CUTTY SARK CANARY WHARF This highly automated network London’s most advanced London Bridge handles over This new super highway across The new Emirates Airline links Canary Wharf south Canary Wharf central Greenwich and UNESCO Canary commerce, DLR, links the Capital’s financial tube line and service 54 million passengers a year the Capital will have an London’s largest entertainment and Plaza and shopping World Heritage Jubilee Line and Crossrail centres, Royal Greenwich and connects at Canary Wharf for with mainline and Thameslink interchange at Canary Wharf, venues - crossing the river in London City Airport in minutes. direct travel to Westminster services departing every 3 significantly cutting journey just 5 minutes with cars running and The West End. minutes. It is the fourth busiest times when operational from every 30 seconds. hub in the UK. 2017. Liverpool The Barbican Street Aldgate Canning Town Custom MINUTE MINUTES MINUTES MINUTES Limehouse 1 3 5 6 St Paul’s Cathedral House Fenchurch Tower Shadwell