John Baskerville, Type-Founder and Printer, 1706-1775

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham, Q2 2019

BIRMINGHAM ABERDEEN SHEFFIELD GLASGOW BRISTOL BIRMINGHAM OFFICEEDINBURGH CARDIFF MARKETNEWCASTLE MANCHESTER LEEDS OCCUPIER HEADLINES TAKE-UP* AVAILABILITY PRIME RENT • Leasing activity improved in Q2 2019 with (sq ft) (sq ft) (£ per sq ft) take-up reaching 320,595 sq ft, a 65% increase £34.50 £35.00 Q2 2019 320,469 Q2 2019 125,000 compared to last quarter. This is 74% above the 10 year quarterly average and is the highest level Q2 2019 vs 10 year Q2 2019 vs 10 year of take-up for Birmingham since Q4 2017. quarterly average 81% quarterly average -68% • The occupational market has been dominated by the arrival of WeWork who has leased 229,042 Q2 2019 Year end 2019 sq ft at three different office locations located 320,595 320,595 220,000 DEVELOPMENT PIPELINE in 55 Colmore Row, Louisa Ryland House and 220,000 277,790 (sq ft) 6 Brindleyplace. With the serviced office sector 277,790 791,000 190,000 growing, B2B accounted for 72% of take-up in Q2. 190,000 486,480 153,000 • Grade A supply continues to fall with 125,000 sq 153,000 194,014 194,014 ft being marketed across three buildings (No 1. 225,000 169,929 169,929 125,000 125,000 120,000 120,000 158,935 Colmore Square, Baskerville House and 1 Newhall 158,935 0 0 Street) at the end of Q2. This is 68% below the 10 Speculative 320,595 year quarterly average. Taking into consideration 320,595 Dates indicate the potential completion date 220,000 220,000 requirements, the market has only four months of of schemes under construction as at Q2 2019. -

Building Birmingham: a Tour in Three Parts of the Building Stones Used in the City Centre

Urban Geology in the English Midlands No. 2 Building Birmingham: A tour in three parts of the building stones used in the city centre. Part 2: Centenary Square to Brindleyplace Ruth Siddall, Julie Schroder and Laura Hamilton This area of central Birmingham has undergone significant redevelopment over the last two decades. Centenary Square, the focus of many exercises, realised and imagined, of civic centre planning is dominated by Symphony Hall and new Library of Birmingham (by Francine Houben and completed in 2013) and the areas west of Gas Street Basin are unrecognisable today from the derelict industrial remains and factories that were here in the 1970s and 80s. Now this region is a thriving cultural and business centre. This walking tour takes in the building stones used in old and new buildings and sculpture from Centenary Square, along Broad Street to Oozells Square, finishing at Brindleyplace. Brindleyplace; steps are of Portland Stone and the paving is York Stone, a Carboniferous sandstone. The main source on architecture, unless otherwise cited is Pevsner’s Architectural Guide (Foster, 2007) and information on public artworks is largely derived from Noszlopy & Waterhouse (2007). This is the second part in a three-part series of guides to the building stones of Birmingham City Centre, produced for the Black Country Geological Society. The walk extends the work of Shilston (1994), Robinson (1999) and Schroder et al. (2015). The walk starts at the eastern end of Centenary Square, at the Hall of Memory. Hall of Memory A memorial to those who lost their lives in the Great War, The Hall of Memory has a prominent position in the Gardens of Centenary Square. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 14 March 2019

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 14 March 2019 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the South team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Approve - Subject to 9 2018/05638/PA 106 Legal Agreement Warwickshire County Cricket Ground Land east of Pershore Road and north of Edgbaston Road Edgbaston B5 Full planning application for the demolition of existing buildings and the development of a residential-led mixed use building containing 375 residential apartments (Use Class C3), ground floor retail units (Use Classes A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5), a gym (Use Class D2), plan, storage, residential amenity areas, site access, car parking, cycle parking, hard and soft landscaping and associated works, including reconfiguration of existing stadium car parking, security fence-line and spectator entrances, site access and hard and soft landscaping. residential amenity areas, site access, car parking, cycle parking, hard and soft landscaping and associated works, including reconfiguration of existing stadium car parking, security fence-line and spectator entrances, site access and hard and soft landscaping. Approve-Conditions 10 2019/00112/PA 45 Ryland Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2BN Erection of two and three storey side and single storey rear extensions Page 1 of 2 Director, Inclusive Growth Approve-Conditions 11 2018/06724/PA Land at rear of Charlecott Close Moseley Birmingham B13 0DE Erection of a two storey residential building consisting of four flats with associated landscaping and parking Approve-Conditions 12 2018/07187/PA Weoley Avenue Lodge Hill Cemetery Lodge Hill Birmingham B29 6PS Land re-profiling works construction of a attenuation/ detention basin Approve-Conditions 13 2018/06094/PA 4 Waldrons Moor Kings Heath Birmingham B14 6RS Erection of two storey side and single storey front, side and rear extensions. -

13A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

13A bus time schedule & line map 13A Birmingham - Blackheath via Bearwood View In Website Mode The 13A bus line (Birmingham - Blackheath via Bearwood) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birmingham: 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM (2) Blackheath: 6:10 AM - 11:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 13A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 13A bus arriving. Direction: Birmingham 13A bus Time Schedule 48 stops Birmingham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:05 AM - 11:15 PM Monday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Sainsburys, Blackheath 7 Halesowen Street, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Tuesday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Blackheath Market, Blackheath Wednesday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Market Place, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Thursday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Green Lane, Hurst Green Friday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Clement Rd, Hurst Green Saturday 5:58 AM - 11:15 PM Nimmings Road, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Church Street, Hurst Green Nimmings Rd, Hurst Green 13A bus Info Direction: Birmingham Brandon Rd, Hurst Green Stops: 48 Fairƒeld Road, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Trip Duration: 46 min Line Summary: Sainsburys, Blackheath, Blackheath Narrow Lane, Hurst Green Market, Blackheath, Green Lane, Hurst Green, Clement Rd, Hurst Green, Church Street, Hurst Green, Middleƒeld Ave, Hurst Green Nimmings Rd, Hurst Green, Brandon Rd, Hurst Middleƒeld Gardens, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Green, Narrow Lane, Hurst Green, Middleƒeld Ave, Hurst Green, M5 Flyover, Hurst Green, Pitƒelds Close, M5 -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the East team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Defer – Informal Approval 8 2016/08285/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Demolition of existing extension and stable block, repair and restoration works to Rookery House to convert to 15 no. one & two-bed apartments with cafe/community space. Residential development comprising 40 no. residential dwellinghouses on adjoining depot sites to include demolition of existing structures and any associated infrastructure works. Repair and refurbishment of Entrance Lodge building. Refer to DCLG 9 2016/08352/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Listed Building Consent for the demolition of existing single storey extension, chimney stack, stable block and repair and restoration works to include alterations to convert Rookery House to 15 no. self- contained residential apartments and community / cafe use - (Amended description) Approve - Conditions 10 2017/04018/PA 57 Stoney Lane Yardley Birmingham B25 8RE Change of use of the first floor of the public house and rear detached workshop building to 18 guest bedrooms with external alterations and parking Page 1 of 2 Corporate Director, Economy Approve - Conditions 11 2017/03915/PA 262 High Street Erdington Birmingham B23 6SN Change of use of ground floor retail unit (Use class A1) to hot food takeaway (Use Class A5) and installation of extraction flue to rear Approve - Conditions 12 2017/03810/PA 54 Kitsland Road Shard End Birmingham B34 7NA Change of use from A1 retail unit to A5 hot food takeaway and installation of extractor flue to side Approve - Conditions 13 2017/02934/PA Stechford Retail Park Flaxley Parkway Birmingham B33 9AN Reconfiguration of existing car parking layout, totem structures and landscaping. -

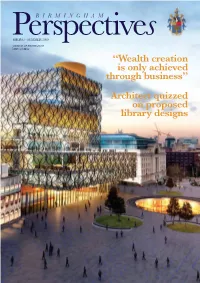

Wealth Creation Is Only Achieved Through Business” Architect Quizzed on Proposed Library Designs Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.Qxd 27/7/09 3:16 Pm Page 2

Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.qxd 27/7/09 3:16 pm Page 1 BIRMINGHAM PerspectiveSPRING - SUMMER 2009 s JOURNAL OF BIRMINGHAM CIVIC SOCIETY “Wealth creation is only achieved through business” Architect quizzed on proposed library designs Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.qxd 27/7/09 3:16 pm Page 2 “The most ambitious and far reaching citywide development project ever undertaken in the UK” Cllr Mike Whitby Leader, Birmingham City Council Birmingham is a great international city, renowned for civic innovation, urban invention, racial and cultural diversity, as well as its creative and educational achievements. The city has made tremendous progress over the last twenty years, regularly being hailed as one of Europe’s success stories, with over £10 billion of planned investment in the city centre alone. However, the city has changed dramatically over the last twenty years, especially with the changes to the inner ring road, making the city centre much larger. Both physically and economically new challenges and new opportunities are now on the agenda, and a new masterplan is needed that will help to unleash the tremendous potential of creativity and diversity of what is the youngest city in Europe. Covering the greater city centre, the full 800 hectares out to the ring road, the Big City Plan will shape and revitalise Birmingham’s city centre over the next twenty years - physically, economically, culturally, creatively - and there will be extensive engagement with colleagues, partners, stakeholders and our citizens to help achieve this. For more information please visit www.bigcityplan.org.uk Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.qxd 27/7/09 3:16 pm Page 3 Birmingham Perspectives Spring - Summer 2009 Contents Does the city have the know-how to Front cover: Concept design for the new Library see recovery? I was fortunate to attend the Birmingham 10 Digby, Lord Jones of Birmingham champions the city's skills. -

Architects' Narratives of the Post-War Reconstruction of Birmingham

Centre for Environment and Society Research Working Paper series no. 9 Stories from the ‘Big Heart of England’: architects’ narratives of the post-war reconstruction of Birmingham David Adams Stories from the ‘Big Heart of England’: architects’ narratives of the post-war reconstruction of Birmingham David Adams Lecturer in Planning Birmingham School of the Built Environment, Birmingham City University Working Paper Series, no. 9 2012 ISBN 978-1-904839-55-2 © Author, 2012 Published by Birmingham City University Centre for Environment and Society Research Faculty of Technology, Engineering and the Environment City Centre campus, Millennium Point, Curzon Street, Birmingham, B4 7XG, UK ii CONTENTS Contents ii Abstract ii Acknowledgements ii Introduction 1 The research approach 2 Different ways of seeing? The role of architects and other design professionals 4 Tensions between ideal and compromised realities 6 Compromised visions 6 Compromised reality – social life of a building 8 Conclusion 11 References 12 Appendix 1: James Roberts interviewed on 11 December 2009 by David Adams 15 Appendix 2: John Madin: interviewed on 18 December 2009 by David Adams 37 Abstract The period of concentrated reconstruction within British city centres in the years following the end of the Second World War continues to attract the interest of a range of academic disciplines. Many studies of the post-war reconstruction of British towns and cities have displayed a particular fascination with nationally-important planners and architects and there have been some recent significant oral accounts that have sought to chart the influence of prominent architects in shaping post-Second World War urban environments. Drawing specifically on recently-collected oral history narratives from James Roberts and John Madin, two of the most important locally-trained post-war architects to shape the reconstruction of Birmingham (UK), this paper explores the extent to which their artistic visions for the heart of Britain’s second city were tempered during the design and development process. -

42 Bridge Road Alveley Bridgnorth Shropshire Wv15 6JU

42 Bridge Road Alveley Bridgnorth Shropshire Wv15 6JU tel: 01746 781 033 mobile: 0797 333 0706 e-mail: [email protected] 15th November 2019 GEOL SOC: BUILDING STONES OF BIRMINGHAM - PART 2: CENTENARY SQUARE TO BRINDLEYPLACE BY ANDREW HARRISON approx words: 1770 Tuesday 21st May 2019: Geological Society: West Midlands Regional Group. Tour of Birmingham’s Building Stones, Part 3: Centenary Square to Brindleyplace, Led by Julie Schroder. In May 2019, Geological Society West Midlands Regional Group (Geol Soc, WMRG) members met in Central Birmingham to view more of the City’s building stones. Part 1 was undertaken in May 2018 and covered the section of trail between Victoria Square and Allied Irish Bank, off Cathedral Square. Part 2 was undertaken in November 2018 and covered Trail 3 around the Bullring Centre. Once again, the group was led by Julie Schroder (Black Country Geological Society), who has been instrumental in pulling together these Birmingham building stone trails. This time 13 Geol Soc WMRG members met for 18:00 next to the Hall of memory on Centenary Square, where Julie provided an introduction to the evening. The route covered was generally along Trail 2. Starting towards the eastern end of Centenary Square our first stop included the Hall of Memory, the Baskerville Monument and Baskerville House. The Hall of memory is a war memorial completed in 1925 to commemorate Birmingham citizens lost during the First World War. The Baskerville Memorial pays homage to John Baskerville, letter founder (1706-1775), who lived in the vicinity of Centenary Square between 1748 and 1775. -

CENTENARY SQUARE Our Lighting Strategy Uses Both Ambient and Feature Lighting to a Create High Quality Contemporary Evening Space

RO Lighting Columns G F M N T I H N E A PLACE IN TIME R P A Lighting A E S L T Illuminated Water CENTENARY SQUARE Our lighting strategy uses both Ambient and Feature lighting to a create high quality contemporary evening space. Transitional and Gateway lighting draw users into the square and supports the feeling of safety and security by creating welcoming entrance zones. Break-out feature zones create pockets of excitement and break the space down to enhance the feeling of making progress through this large square. The ability to see the next breakout feature draws users through with a visual connection. The feature zones are connected using linking effect lighting treatments working in harmony with the feature zones. Illuminated Trees Our intention is to create a magical space and a memorable place, that users will feel comfortable and safe during the hours of darkness. Pool of Memory - A Grand Gesture - the Pool of Memory provides a world class setting for the Hall of Memory. A Place of Retreat - Here Dynamic Calm the heritage of the city is Water remembered with a space for reflection and contemplation. This is an area of calm and Our Centenary Maze App contemplation where people of allows visitors to take control all ages can come together and of the water jets resulting remember the past. The Hall in a fun (if wet!) interactive sits in a pool of water providing experience. Activated from stillness and reflection. This is a the library terrace, users place to stop and rest, to meet have a birds eye view of the with friends and with strangers action while footfall to the and to enjoy the springtime sun. -

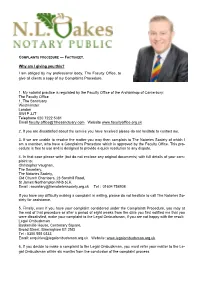

Complaints Procedure — Factsheet

COMPLAINTS PROCEDURE — FACTSHEET. Why am I giving you this? I am obliged by my professional body, The Faculty Office, to give all clients a copy of my Complaints Procedure. 1. My notarial practice is regulated by the Faculty Office of the Archbishop of Canterbury: The Faculty Office 1, The Sanctuary Westminster London SW1P 3JT Telephone 020 7222 5381 Email [email protected] Website www.facultyoffice.org.uk 2. If you are dissatisfied about the service you have received please do not hesitate to contact me. 3. If we are unable to resolve the matter you may then complain to The Notaries Society of which I am a member, who have a Complaints Procedure which is approved by the Faculty Office. This pro- cedure is free to use and is designed to provide a quick resolution to any dispute. 4. In that case please write (but do not enclose any original documents) with full details of your com- plaint to: Christopher Vaughan, The Secretary, The Notaries Society, Old Church Chambers, 23 Sandhill Road, St James Northampton NN5 5LH. Email : [email protected] Tel : 01604 758908 If you have any difficulty making a complaint in writing, please do not hesitate to call The Notaries So- ciety for assistance. 5. Finally, even if you have your complaint considered under the Complaints Procedure, you may at the end of that procedure or after a period of eight weeks from the date you first notified me that you were dissatisfied, make your complaint to the Legal Ombudsman, if you are not happy with the result: Legal Ombudsman Baskerville House, Centenary Square, Broad Street, Birmingham B1 2ND Tel : 0300 555 0333 Email: [email protected] Website: www.legalombudsman.org.uk 6. -

12A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

12A bus time schedule & line map 12A Birmingham - Dudley via Oldbury View In Website Mode The 12A bus line (Birmingham - Dudley via Oldbury) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bearwood: 6:39 PM (2) Birmingham: 6:10 AM - 6:30 PM (3) Dudley: 5:55 AM - 6:02 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 12A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 12A bus arriving. Direction: Bearwood 12A bus Time Schedule 39 stops Bearwood Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Dudley Bus Station, Dudley Gatehouse Fold, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Tuesday Not Operational St John's Rd, Kates Hill Wednesday Not Operational New Rowley Rd, Dixons Green Thursday Not Operational 56 Bennetts Hill, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Friday Not Operational Oakham Avenue, Dixons Green Saturday 6:39 PM Oakham Road, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Tansley Hill Ave, Tansley Hill Regent Rd, Oakham 12A bus Info Gibbet Hill, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Direction: Bearwood Stops: 39 Wheatsheaf Rd, Grace Mary Estate Trip Duration: 37 min Line Summary: Dudley Bus Station, Dudley, St John's Sampson Close, Grace Mary Estate Rd, Kates Hill, New Rowley Rd, Dixons Green, Sampson Close, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Oakham Avenue, Dixons Green, Tansley Hill Ave, Tansley Hill, Regent Rd, Oakham, Wheatsheaf Rd, Tower Rise, Grace Mary Estate Grace Mary Estate, Sampson Close, Grace Mary Tower Rise, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Estate, Tower Rise, Grace -

Perry Barr Constituency Economic & Employment Profile

Perry Barr Constituency Economic & Employment Profile March 2015 Economic Research & Policy Economy Directorate Perry Bridge Flikr Creative Commons Contents Introduction 2 Perry Barr Key Facts 3 1. Business 4 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Employment 4 1.2.1 Private Sector Employment 5 1.2.2 Employment by Sector 5 1.3 Employment Forecasts 6 1.4 Enterprise 6 1.4.1 Business Numbers 6 1.4.2 Businesses by Sector 7 2. Place 8 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 Development & Regeneration 9 2.3 Deprivation & Child Poverty 9 2.3.1 Child Poverty 10 3. People 11 3.1 Introduction 11 3.2 Working Age Population 11 3.2.1 Ethnic Structure 12 3.3 Qualifications & Skills 12 3.3.1 NVQ Qualifications 13 3.4 Economic Activity 13 3.5 Unemployment 14 3.5.1 Youth Unemployment 15 3.5.2 Unemployment by Ethnicity 16 Introduction The Perry Barr constituency is fourth largest constituency in proportion than the city located in the north of Birmingham. The constituency average of 42.1% and over Birmingham and comprises the has a population of 107,090, four times the national average four wards of Handsworth the fourth largest population of of 14.6%. Wood, Lozells and East all the constituencies in the This report provides detailed Handsworth, Oscott and Perry city; Perry Barr has the fourth information on the Perry Barr Barr. The constituency forms smallest population density of constituency and intra- the northwest boundary of the the 10 constituencies at 43 constituency comparisons by city. The four wards are largely people per hectare.