Architects' Narratives of the Post-War Reconstruction of Birmingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Broad Street

100 Broad St | BIRMINGHAM 100 BROAD STREET DESIGN AND ACCESS STATEMENT July 2019 CONTENTS 100 Broad St | BIRMINGHAM 1.00 Introduction/Executive Summary 2.00 Project Brief 7.00 Design 8.00 Access and Servicing 7.01 Pre-Application Response 8.01 Access to Site 3.00 Site Information 7.02 Concept - Big Moves 8.02 Internal Circulation 3.01 Site Location 7.03 Architectural Strategy 8.03 Façade Access/ Maintenance Strategy 3.02 Site Context 7.04 Design Timeline 8.04 Inclusive Access Strategy 3.03 Site and Context Land Use 7.05 Broad Street Massing 8.05 Refuse Strategy 3.04 Building Heights 7.06 Broad Street Section 8.06 Car Parking and Cycle Storage 3.05 Notable Buildings/ Character of the Area 7.07 Proposed Massing 8.07 Security Strategy 3.06 Emerging Scale 7.08 Floor Plans 8.08 Fire Strategy 3.07 Walking Distances 7.09 Schedule of Accommodation 8.09 Wind Strategy 3.08 Transport and Links 7.10 Typical Apartment Layouts 3.09 Conservation Area 7.11 Lower Levels 9.00 Landscape 7.12 Amenity Space 9.01 Landscape Strategy and Public Realm 4.00 Contextual Analysis 7.13 Sky Lounge 9.02 Landscape Arrangement Diagram 4.01 Historical Context 7.14 Elevations 9.03 Proposed Landscape Plan 4.02 Topography 7.15 Bay Elevations 9.04 Landscape Precedent and Design Aspiration 4.03 Built Space/ Open Space Analysis 7.16 Façade Precedents 9.05 Landscape Material Palette 7.17 Sections 9.06 Landscape Visuals 5.00 Urban Design Strategy 7.18 Proposed Street Elevations 9.07 Metro Landscape Strategy 7.19 3D Views 5.01 Policy Context 7.20 Visual Impact Analysis 5.02 Policy -

Birmingham, Q2 2019

BIRMINGHAM ABERDEEN SHEFFIELD GLASGOW BRISTOL BIRMINGHAM OFFICEEDINBURGH CARDIFF MARKETNEWCASTLE MANCHESTER LEEDS OCCUPIER HEADLINES TAKE-UP* AVAILABILITY PRIME RENT • Leasing activity improved in Q2 2019 with (sq ft) (sq ft) (£ per sq ft) take-up reaching 320,595 sq ft, a 65% increase £34.50 £35.00 Q2 2019 320,469 Q2 2019 125,000 compared to last quarter. This is 74% above the 10 year quarterly average and is the highest level Q2 2019 vs 10 year Q2 2019 vs 10 year of take-up for Birmingham since Q4 2017. quarterly average 81% quarterly average -68% • The occupational market has been dominated by the arrival of WeWork who has leased 229,042 Q2 2019 Year end 2019 sq ft at three different office locations located 320,595 320,595 220,000 DEVELOPMENT PIPELINE in 55 Colmore Row, Louisa Ryland House and 220,000 277,790 (sq ft) 6 Brindleyplace. With the serviced office sector 277,790 791,000 190,000 growing, B2B accounted for 72% of take-up in Q2. 190,000 486,480 153,000 • Grade A supply continues to fall with 125,000 sq 153,000 194,014 194,014 ft being marketed across three buildings (No 1. 225,000 169,929 169,929 125,000 125,000 120,000 120,000 158,935 Colmore Square, Baskerville House and 1 Newhall 158,935 0 0 Street) at the end of Q2. This is 68% below the 10 Speculative 320,595 year quarterly average. Taking into consideration 320,595 Dates indicate the potential completion date 220,000 220,000 requirements, the market has only four months of of schemes under construction as at Q2 2019. -

IRONMONGERY What’S Inside

IRONMONGERY What’s inside 04 Bolts 17 Hat & coat hooks 07 Staples & receivers 18 Window fittings 08 Door holders 19 Buttons 09 Hasps & staples 20 Pulleys 11 Latches & catches 21 Miscellaneous 14 Brackets 22 Hinges, hooks & bands 15 Handles 25 Skin packed range 16 Door furniture Guarantee To support the high quality and first class engineering that has gone into the Ironmongery range, the manufacturer gives a ten year guarantee (subject to conditions) against defects due to faulty manufacturing, workmanship or defective material. The manufacturer agrees to replace any defective Ironmongery product free of charge provided the product has been fitted in accordance with the fitting instructions and maintained correctly. Technical Support Comprehensive information and technical support services are available by contacting: Tel: +44 (0)1543 460040 Fax: +44 (0)1543 570050 email: [email protected] Or visit our website: exidor.co.uk There are a number of enhancements we’ve made to the Exidor website. You’ll also find new company info, technical data, and downloadable pdfs of the latest product literature – all presented in a clear and contemporary style that we hope you’ll enjoy. We’re aiming to keep on improving the website, with more new specifiers on the way, and additions to our gallery of products and projects. If you have comments and ideas on ways we can make it even better and more useful, just let us know. Title Introducing the Ironmongery range Exidor Ltd is the British company that manufactures the Duncombe Ironmongery range, in accordance with ISO 9002. The company had over 60 years experience in manufacturing quality ironmongery such as tower bolts, suffolk latches and hasp and staples before introducing the Exidor panic and emergency exit hardware range and taking ownership of the Webb Lloyd range of door furniture. -

Building Birmingham: a Tour in Three Parts of the Building Stones Used in the City Centre

Urban Geology in the English Midlands No. 2 Building Birmingham: A tour in three parts of the building stones used in the city centre. Part 2: Centenary Square to Brindleyplace Ruth Siddall, Julie Schroder and Laura Hamilton This area of central Birmingham has undergone significant redevelopment over the last two decades. Centenary Square, the focus of many exercises, realised and imagined, of civic centre planning is dominated by Symphony Hall and new Library of Birmingham (by Francine Houben and completed in 2013) and the areas west of Gas Street Basin are unrecognisable today from the derelict industrial remains and factories that were here in the 1970s and 80s. Now this region is a thriving cultural and business centre. This walking tour takes in the building stones used in old and new buildings and sculpture from Centenary Square, along Broad Street to Oozells Square, finishing at Brindleyplace. Brindleyplace; steps are of Portland Stone and the paving is York Stone, a Carboniferous sandstone. The main source on architecture, unless otherwise cited is Pevsner’s Architectural Guide (Foster, 2007) and information on public artworks is largely derived from Noszlopy & Waterhouse (2007). This is the second part in a three-part series of guides to the building stones of Birmingham City Centre, produced for the Black Country Geological Society. The walk extends the work of Shilston (1994), Robinson (1999) and Schroder et al. (2015). The walk starts at the eastern end of Centenary Square, at the Hall of Memory. Hall of Memory A memorial to those who lost their lives in the Great War, The Hall of Memory has a prominent position in the Gardens of Centenary Square. -

Traditional Windows: Their Care, Repair and Upgrading

Traditional Windows Their Care, Repair and Upgrading Summary The loss of traditional windows from our older buildings poses one of the major threats to our heritage. Traditional windows and their glazing make an important contribution to the significance of historic areas. They are an integral part of the design of older buildings and can be important artefacts in their own right, often made with great skill and ingenuity with materials of a higher quality than are generally available today. The distinctive appearance of historic hand-made glass is not easily imitated in modern glazing. Windows are particularly vulnerable elements of a building as they are relatively easily replaced or altered. Such work often has a profound affect not only on the building itself but on the appearance of street and local area. With an increasing emphasis being placed on making existing buildings more energy efficient, replacement windows have become a greater threat than ever before to the character of historic buildings and areas. This guidance covers both timber and metal windows and is aimed at building professionals and property-owners. It sets out to show the significance of traditional domestic windows by charting their history over centuries of technical development and fashion. Detailed technical advice is then provided on their maintenance, repair and thermal upgrading as well as on their replacement. This guidance was written and compiled by David Pickles, Iain McCaig and Chris Wood with assistance from Nick Molyneux and Eleni Makri. First published by English Heritage September 2014. This edition published by Historic England February 2017. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. -

Authentic, Vintage & Antique Hardware & Goods

AUTHENTIC, VINTAGE & ANTIQUE HARDWARE & GOODS MASTER PRODUCT BROCHURE EDITION-08 A GALLERY OF INSPIRATION www.cottinghamcollection.co.uk WELCOME AUTHENTIC, VINTAGE & ANTIQUE HARDWARE & GOODS COTTINGHAM COLLECTION INDEX INFORMATION ARCHITECTURAL HARDWARE Welcome to Inspiration 2 Finishes 4 Where to buy 121 “The Cottingham Collection” Wall Plaques 76 Shelf Brackets 79 Pull Handles 83 The Cottingham Collection range has and design products that will suit your CABINET HARDWARE Hinges 85 been born out of a desire to create property and still be beautiful for years Door Furniture 88 Authentic Hardware and Household to come, aging naturally over time. Knobs 08 Seating 92 Pull Handles 13 Window Furniture 93 goods. Flush Handles 16 Table Legs 94 We hope you enjoy the inspiration we Drop Handles 18 Swivel Brackets 96 What sets the range apart from other believe this brochure will bring you and Hinges 21 Door Knobs 97 Lever Handle 101 brands of ironmongery is the unique invite you to also visit the CC website Hasp & Staple 30 Chest Corners 31 Air Bricks, Vents & Trivets 102 designs and finishes. Whilst the bulk www.cottinghamcollection.co.uk where Cup Handles 33 Radiator Accessories 103 of mass produced ironmongery on the the latest products & developments are Studs & Nails 38 Shopfitting Accessories 104 Miscellaneous 105 market today is finished in black epoxy, listed. Latches 40 Miscellaneous 41 lacquer or beeswax, the CC range is handfinished using traditional methods. LIGHTING All cast iron products go through a 5 HOOKS stage hand finishing process to achieve a natural authentic finish that will age Ceramic 44 Pendant Shades 108 Cast Iron 46 Anglepoise’s 110 naturally over time. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 14 March 2019

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 14 March 2019 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the South team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Approve - Subject to 9 2018/05638/PA 106 Legal Agreement Warwickshire County Cricket Ground Land east of Pershore Road and north of Edgbaston Road Edgbaston B5 Full planning application for the demolition of existing buildings and the development of a residential-led mixed use building containing 375 residential apartments (Use Class C3), ground floor retail units (Use Classes A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5), a gym (Use Class D2), plan, storage, residential amenity areas, site access, car parking, cycle parking, hard and soft landscaping and associated works, including reconfiguration of existing stadium car parking, security fence-line and spectator entrances, site access and hard and soft landscaping. residential amenity areas, site access, car parking, cycle parking, hard and soft landscaping and associated works, including reconfiguration of existing stadium car parking, security fence-line and spectator entrances, site access and hard and soft landscaping. Approve-Conditions 10 2019/00112/PA 45 Ryland Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2BN Erection of two and three storey side and single storey rear extensions Page 1 of 2 Director, Inclusive Growth Approve-Conditions 11 2018/06724/PA Land at rear of Charlecott Close Moseley Birmingham B13 0DE Erection of a two storey residential building consisting of four flats with associated landscaping and parking Approve-Conditions 12 2018/07187/PA Weoley Avenue Lodge Hill Cemetery Lodge Hill Birmingham B29 6PS Land re-profiling works construction of a attenuation/ detention basin Approve-Conditions 13 2018/06094/PA 4 Waldrons Moor Kings Heath Birmingham B14 6RS Erection of two storey side and single storey front, side and rear extensions. -

Library of Birmingham Supplement

© Christian Richters www.libraryofbirmingham.com Published by History West Midlands www.historywm.com THE NEW LIBRARY OF BIRMINGHAM he £188.8 million Library of Birmingham stands on Centenary Square, at the heart of Birmingham; an area of the city not far from New Street Station which is currently undergoing major refurbishment. It has been built on the site Tof a former car park and is joined with the neighbouring Birmingham Repertory Theatre. Dutch architects Mecanoo designed the building, the award-winning support services and construction company Carillion was the principal contractor, and Capita Symonds was the project manager. © Simon Hadley The new library has ten levels: nine above ground and one lower Brian Gambles, Project Director, Library of Birmingham ground floor. The first to eighth floors of the building are wrapped by an intricate metal façade, reflecting the gasometers, tunnels, canals irmingham has always been a city that and viaducts which fuelled Birmingham’s industrial growth. has valued libraries and the city’s Central Library, built in 1974, was one Highlights of the new building include a studio theatre seating of the biggest in Europe and 300 people, a performance area and children’s spaces, two outdoor garden terraces, an outdoor amphitheatre in Centenary Bwelcomed a huge number of visitors through its doors every day - children and adults reading Square, and a panoramic viewing gallery offering stunning views for pleasure, as well as students and adults from one of the highest points in the city. hungry to learn. A 'Golden Box' of secure archive storage occupies two levels of the The new Library of Birmingham is taking library building, within which the city’s internationally significant collection services to a whole new level, redefining what a of archives, photography and rare books is housed. -

The Failure of the Preservation of Brutalism in Birmingham, England

The Failure of the Preservation of Brutalism in Birmingham, England Kelsey Dootson B.A. in History Missouri State University, Springfield, Missouri, 2016 Thesis Committee: Sheila Crane, chair Richard Guy Wilson Andrew Johnston A Thesis Presented to Faculty of the Department of Architectural History of the School of Architecture Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architectural History School of Architecture UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA Charlottesville, Virginia May 2018 2 Table of Contents List of Illustrations ..................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... 4 Introductions ............................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Destruction and Reconstruction ................................................................................ 10 Chapter 2: Brutalism in Birmingham ......................................................................................... 23 Chapter 3: Preservation in the City ............................................................................................ 37 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 47 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................ -

13A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

13A bus time schedule & line map 13A Birmingham - Blackheath via Bearwood View In Website Mode The 13A bus line (Birmingham - Blackheath via Bearwood) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birmingham: 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM (2) Blackheath: 6:10 AM - 11:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 13A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 13A bus arriving. Direction: Birmingham 13A bus Time Schedule 48 stops Birmingham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:05 AM - 11:15 PM Monday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Sainsburys, Blackheath 7 Halesowen Street, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Tuesday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Blackheath Market, Blackheath Wednesday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Market Place, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Thursday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Green Lane, Hurst Green Friday 5:37 AM - 11:15 PM Clement Rd, Hurst Green Saturday 5:58 AM - 11:15 PM Nimmings Road, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Church Street, Hurst Green Nimmings Rd, Hurst Green 13A bus Info Direction: Birmingham Brandon Rd, Hurst Green Stops: 48 Fairƒeld Road, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Trip Duration: 46 min Line Summary: Sainsburys, Blackheath, Blackheath Narrow Lane, Hurst Green Market, Blackheath, Green Lane, Hurst Green, Clement Rd, Hurst Green, Church Street, Hurst Green, Middleƒeld Ave, Hurst Green Nimmings Rd, Hurst Green, Brandon Rd, Hurst Middleƒeld Gardens, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Green, Narrow Lane, Hurst Green, Middleƒeld Ave, Hurst Green, M5 Flyover, Hurst Green, Pitƒelds Close, M5 -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the East team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Defer – Informal Approval 8 2016/08285/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Demolition of existing extension and stable block, repair and restoration works to Rookery House to convert to 15 no. one & two-bed apartments with cafe/community space. Residential development comprising 40 no. residential dwellinghouses on adjoining depot sites to include demolition of existing structures and any associated infrastructure works. Repair and refurbishment of Entrance Lodge building. Refer to DCLG 9 2016/08352/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Listed Building Consent for the demolition of existing single storey extension, chimney stack, stable block and repair and restoration works to include alterations to convert Rookery House to 15 no. self- contained residential apartments and community / cafe use - (Amended description) Approve - Conditions 10 2017/04018/PA 57 Stoney Lane Yardley Birmingham B25 8RE Change of use of the first floor of the public house and rear detached workshop building to 18 guest bedrooms with external alterations and parking Page 1 of 2 Corporate Director, Economy Approve - Conditions 11 2017/03915/PA 262 High Street Erdington Birmingham B23 6SN Change of use of ground floor retail unit (Use class A1) to hot food takeaway (Use Class A5) and installation of extraction flue to rear Approve - Conditions 12 2017/03810/PA 54 Kitsland Road Shard End Birmingham B34 7NA Change of use from A1 retail unit to A5 hot food takeaway and installation of extractor flue to side Approve - Conditions 13 2017/02934/PA Stechford Retail Park Flaxley Parkway Birmingham B33 9AN Reconfiguration of existing car parking layout, totem structures and landscaping. -

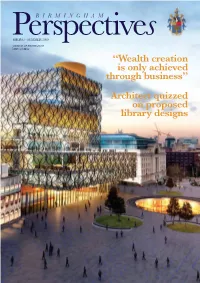

Wealth Creation Is Only Achieved Through Business” Architect Quizzed on Proposed Library Designs Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.Qxd 27/7/09 3:16 Pm Page 2

Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.qxd 27/7/09 3:16 pm Page 1 BIRMINGHAM PerspectiveSPRING - SUMMER 2009 s JOURNAL OF BIRMINGHAM CIVIC SOCIETY “Wealth creation is only achieved through business” Architect quizzed on proposed library designs Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.qxd 27/7/09 3:16 pm Page 2 “The most ambitious and far reaching citywide development project ever undertaken in the UK” Cllr Mike Whitby Leader, Birmingham City Council Birmingham is a great international city, renowned for civic innovation, urban invention, racial and cultural diversity, as well as its creative and educational achievements. The city has made tremendous progress over the last twenty years, regularly being hailed as one of Europe’s success stories, with over £10 billion of planned investment in the city centre alone. However, the city has changed dramatically over the last twenty years, especially with the changes to the inner ring road, making the city centre much larger. Both physically and economically new challenges and new opportunities are now on the agenda, and a new masterplan is needed that will help to unleash the tremendous potential of creativity and diversity of what is the youngest city in Europe. Covering the greater city centre, the full 800 hectares out to the ring road, the Big City Plan will shape and revitalise Birmingham’s city centre over the next twenty years - physically, economically, culturally, creatively - and there will be extensive engagement with colleagues, partners, stakeholders and our citizens to help achieve this. For more information please visit www.bigcityplan.org.uk Perspectives Spring - Summer Final.qxd 27/7/09 3:16 pm Page 3 Birmingham Perspectives Spring - Summer 2009 Contents Does the city have the know-how to Front cover: Concept design for the new Library see recovery? I was fortunate to attend the Birmingham 10 Digby, Lord Jones of Birmingham champions the city's skills.