The Libertarian Middle Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Social Enterprise

A Third Way Out?— On Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Social Enterprise Chik Ho Ning Cultural Management, Chung Chi College Social enterprise is a rising form of business which strives for common good as an ultimate purpose. The Social Enterprise Alliance in Hong Kong stresses three characteristics of social enterprises: addressing social needs and serving the common good, using commercial activity as a strong revenue driver as compared to relying on donations, and holding the common good as the primary purpose (“The Case for Social Enterprise Alliance”). By another definition, provided by the Home Affairs Department of Hong Kong, a social enterprise strives for social goods in the area of providing service for the community while creating employment and training opportunities for the socially vulnerable. It is also important that social enterprises reinvest their earned profits for the social objectives, instead of distributing them to shareholders. (“What is Social Enterprise.”) One shall wonder, how does this relate to the existing business models and ideologies? In the following, I shall draw attention to ideas of Adam Smith and Karl Marx, and, in my wild imagination, their possible comments to social enterprises. Examples of social enterprises in Hong Kong shall be 26 與人文對話 In Dialogue with Humanity quoted. The essay will end with a discussion on social enterprises as “the third way”. On Adam Smith and Social Enterprise Smith is honoured as the Father of Economy, and his ideology drives the operation of a capitalistic society. In The Wealth of Nations, he emphasises the activities in a free market, driven by self-interest of individuals and led by an “invisible hand”. -

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

Forms of Government

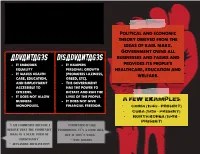

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Mill's "Very Simple Principle": Liberty, Utilitarianism And

MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE": LIBERTY, UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM MICHAEL GRENFELL submitted for degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H^S £ S F 6SI6 ABSTRACT OF THESIS MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE'*: LIBERTY. UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM 1 The thesis aims to examine the political consequences of applying J.S. Mill's "very simple principle" of liberty in practice: whether the result would be free-market liberalism or socialism, and to what extent a society governed in accordance with the principle would be free. 2 Contrary to Mill's claims for the principle, it fails to provide a clear or coherent answer to this "practical question". This is largely because of three essential ambiguities in Mill's formulation of the principle, examined in turn in the three chapters of the thesis. 3 First, Mill is ambivalent about whether liberty is to be promoted for its intrinsic value, or because it is instrumental to the achievement of other objectives, principally the utilitarian objective of "general welfare". -

The Third Way and the Governance of the Social in Britain Jérôme Tournadre

The Third Way and the governance of the social in Britain Jérôme Tournadre To cite this version: Jérôme Tournadre. The Third Way and the governance of the social in Britain. A city of one’s own, Ashgate, pp.201-212, 2008. halshs-00649541 HAL Id: halshs-00649541 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00649541 Submitted on 9 Dec 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHAPTER TWELVE The ‘Third Way’ and the Governance of the Social in Britain Jérôme Tournadre-Plancq Regardless of the ‘world of Welfare’ in which it functions - to use the term coined by Gøsta Esping-Andersen (Esping-Andersen 1990) - the State has, during a large part of the twentieth century, come to play an essential role in the handling of welfare in liberal democracies. This does not mean that its role amounts to exercising a monopoly. Providing a counterweight to the market in the social-democratic ‘compromise’, the Welfare State often emerges, in the political reflection of the majority of the post-war centre-left, as the most reliable guarantor for the common good. The Social (Donzelot 1984) is then considered as the best way to reinforce this idea. -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Free to Choose

June 9, 2005 COMMENTARY Free to Choose By MILTON FRIEDMAN June 9, 2005; Page A16 Little did I know when I published an article in 1955 on "The Role of Government in Education" that it would lead to my becoming an activist for a major reform in the organization of schooling, and indeed that my wife and I would be led to establish a foundation to promote parental choice. The original article was not a reaction to a perceived deficiency in schooling. The quality of schooling in the United States then was far better than it is now, and both my wife and I were satisfied with the public schools we had attended. My interest was in the philosophy of a free society. Education was the area that I happened to write on early. I then went on to consider other areas as well. The end result was "Capitalism and Freedom," published seven years later with the education article as one chapter. With respect to education, I pointed out that government was playing three major roles: (1) legislating compulsory schooling, (2) financing schooling, (3) administering schools. I concluded that there was some justification for compulsory schooling and the financing of schooling, but "the actual administration of educational institutions by the government, the 'nationalization,' as it were, of the bulk of the 'education industry' is much more difficult to justify on [free market] or, so far as I can see, on any other grounds." Yet finance and administration "could readily be separated. Governments could require a minimum of schooling financed by giving the parents vouchers redeemable for a given sum per child per year to be spent on purely educational services. -

If Not Left-Libertarianism, Then What?

COSMOS + TAXIS If Not Left-Libertarianism, then What? A Fourth Way out of the Dilemma Facing Libertarianism LAURENT DOBUZINSKIS Department of Political Science Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Burnaby, B.C. Canada V5A 1S6 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.sfu.ca/politics/faculty/full-time/laurent_dobuzinskis.html Bio-Sketch: Laurent Dobuzinskis’ research is focused on the history of economic and political thought, with special emphasis on French political economy, the philosophy of the social sciences, and public policy analysis. Abstract: Can the theories and approaches that fall under the more or less overlapping labels “classical liberalism” or “libertarianism” be saved from themselves? By adhering too dogmatically to their principles, libertarians may have painted themselves into a corner. They have generally failed to generate broad political or even intellectual support. Some of the reasons for this isolation include their reluctance to recognize the multiplicity of ways order emerges in different contexts and, more 31 significantly, their unshakable faith in the virtues of free markets renders them somewhat blind to economic inequalities; their strict construction of property rights and profound distrust of state institutions leave them unable to recommend public policies that could alleviate such problems. The doctrine advanced by “left-libertarians” and market socialists address these substantive weaknesses in ways that are examined in detail in this paper. But I argue that these “third way” movements do not stand any better chance than libertari- + TAXIS COSMOS anism tout court to become a viable and powerful political force. The deeply paradoxical character of their ideas would make it very difficult for any party or leader to gain political traction by building an election platform on them. -

Friedman's Monetary Framework

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Friedman’s Monetary Framework: Some Lessons Ben S. Bernanke t is an honor and a pleasure to have this opportunity, on the anniversary of Milton and Rose Friedman’s popular classic, Free to Choose, to speak on I Milton Friedman’s monetary framework and his contributions to the theory and practice of monetary policy. About a year ago, I also had the honor, at a conference at the University of Chicago in honor of Milton’s ninetieth birthday, to discuss the contribution of Friedman’s classic 1963 work with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.1 I mention this earlier talk not only to indicate that I am ready and willing to praise Friedman’s contributions wherever and whenever anyone will give me a venue but also because of the critical influ- ence of A Monetary History on both Friedman’s own thought and on the views of a generation of monetary policymakers. In their Monetary History, Friedman and Schwartz reviewed nearly a cen- tury of American monetary experience in painstaking detail, providing an his- torical analysis that demonstrated the importance of monetary forces in the economy far more convincingly than any purely theoretical or even economet- ric analysis could ever do. Friedman’s close attention to the lessons of history for economic policy is an aspect of his approach to economics that I greatly admire. Milton has never been a big fan of government licensing of profession- als, but maybe he would make an exception in the case of monetary policy- makers.