No. 25. Excavation at Tamlaght, Co. Armagh 2004 AE/03/45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

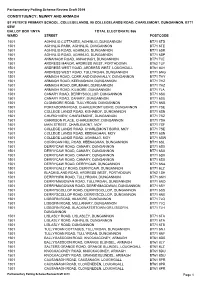

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

Tourism, Arts & Culture Report

Armagh City Banbridge & Craigavon Borough TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE REPORT AUGUST 2016 2 \\ ARMAGH CITY BANBRIDGE & CRAIGAVON BOROUGH INTRODUCTION The purpose of this document is to provide an overview of the topics relating to tourism, arts and culture in Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough to help inform the development of a community plan. KEY FINDINGS Population (2014) Total Population by Age Population 15% 22% 0-15 years 205,711 16-39 years 40-64 years 32% 65+ years 11% of total 32% NI population Tourism Overnight trips (2015) 3% 0.1m of overnight trips 22m trips in Northern Ireland spent Place of Origin Reason for Visit 5% 5% 8% Great Britain Business 18% 34% North America Other 43% Northern Ireland Visiting Friends & Relatives ROI & Other Holiday/Pleasure/Leisure 5% 11% Mainland Europe 69% 2013 - 2015 Accomodation (2015) 1,173 beds Room Occupancy Rates Hotels 531 55% Hotels Bed & Breakfasts, Guesthouses 308 and Guest Accomodation 25% Self Catering 213 Other Commercial Accomodation Hostel 121 TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE AUGUST 2016 // 3 Visitor Attractions (2015) Top three attractions 220,928visits 209,027visits 133,437visits Oxford Island National Kinnego Marina Lough Neagh Nature Reserve Discovery Centre Top three parks and gardens 140,074visits 139,435visits 126,123visits Edenvilla Park Tannaghmore Peatlands Park & Garden Gardens & Rare Breed Animal Farm Arts and Culture Engagement in Arts and Culture Arts Arts Used the public Visited a museum attendance participation library service or science centre Armagh City, Banbridge -

Pastoral Christmas Document

St Patrick’s Cathedral Pastoral Area Consisting of the parishes of Armagh, Cill Chluana, Keady, Derrynoose & Madden, Middletown & Tynan warmly invite you to our Parish Masses, Confessions and events over the Christmas period. Please read our collective schedule overleaf. We hope that this document will be of some use to you and your family who may wish to attend. May we take this opportunity to wish you every blessing during Christmas and the New Year Fr Peter McAnenly ADM VF Fr John McKeever ADM Fr Sean Moore PP Fr Greg Carville PP Christmas and New Year Services in Cill Chluana A Carol Service in preparation for Christmas together with Parish Primary Schools Wednesday 13th December at 7 PM in St. Patrick’s Church, Ballymacnab Christmas Masses St Michael’s Clady Christmas Eve Vigil Mass 6.15 pm Christmas Day 10.00 am St. Mary’s Granemore Christmas Eve Vigil Mass 8.00 pm Christmas Day 10.00 am St. Patrick’s Ballymacnab Christmas Eve Vigil Mass 8.00 pm Christmas Day 11.30 am ( No 9 am Mass) Confessions in preparation for Christmas Before all weekday Masses, week prior to Christmas New Years Day Monday 1 January is the Feast of Mary the Mother of God and World Day of Peace Mass (Novena) Monday 7.30pm - St. Patrick’s Ballymacnab Christmas and New Year Services in Middletown & Tynan All masses etc are in St John's Middletown as Tynan Chapel is currently closed Christmas Masses St. John’s Middletown Christmas Eve Vigil Mass at 8 pm Christmas Day Masses - 10 am and 11.30 am New Years Day Monday 1 January is the Feast of Mary the Mother of God and World Day of Peace Mass at 10 am Confessions in preparation for Christmas will be before and after the 7.30 pm Mass on Thursday 21 December and Saturday 23 December Christmas and New Year Services in Armagh Parish A Carol Service in preparation for Christmas will take place in St Patrick’s Cathedral on Sunday 17 December at 5.00 pm. -

County Report

FOP vl)Ufi , NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE PRICE 85p NET NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE CONTENTS PART 1— EXPLANATORY NOTES AND DEFINITIONS Page Area (hectares) vi Population vi Dwellings vi Private households vii Rooms vii Tenure vii Household amenities viii Cars and garaging ....... viii Non-private establishments ix Usual address ix Age ix Birthplace ix Religion x Economic activity x Presentation conventions xi Administrative divisions xi PART II--TABLES Table Areas for which statistics Page No. Subject of Table are stated 1. Area, Buildings for Habitation and County 1 Population, 1971 2. Population, 1821-1971 ! County 1 3. Population 1966 and 1971, and Intercensal Administrative Areas 1 Changes 4. Acreage, Population, Buildings for Administrative Areas, Habitation and Households District Electoral Divisions 2 and Towns 5. Ages by Single Years, Sex and Marital County 7 Condition 6. Population under 25 years by Individual Administrative Areas 9 Years and 25 years and over by Quinquennial Groups, Sex and Marital Condition 7. Population by Sex, Marital Condition, Area Administrative Areas 18 of Enumeration, Birthplace and whether visitor to Northern Ireland 8. Religions Administrative Areas 22 9. Private dwellings by Type, Households, | Administrative Areas 23 Rooms and Population 10. Dwellings by Tenure and Rooms Administrative Areas 26 11. Private Households by Size, Rooms, Administrative Areas 30 Dwelling type and Population 12. -

Downloaded the Audio Tours

The Ring of Gullion Landscape Conservation Action Plan Newry and Mourne District Council 2/28/2014 Contents The Ring of Gullion Landscape Partnership Board is grateful financial support for this scheme. 2 Contents Contents Executive summary 6 Introduction 9 Plan author 9 Landscape Conservation Action Plan – Scheme Overview 13 Section 1 – Understanding the Ring of Gullion 19 Introduction 19 The Project Boundary 19 Towns and Villages 20 The Landscape Character 30 The Ring of Gullion Landscape 31 Landscape Condition and Sensitivity to Change 32 Ring of Gullion Geodiversity Profile 33 Ring of Gullion Biodiversity Profile 38 The Heritage of the Ring of Gullion 47 Management Information 51 Section 2 – Statement of Significance 53 Introduction 53 Natural Heritage 54 Archaeological and Built Heritage 59 Geological Significance 62 Historical Significance 63 Industrial Heritage 67 Twentieth Century Military Significance 68 3 Contents Cultural and Human Heritage 68 Importance to Local Communities 73 Section 3 – Risks and Opportunities 81 Introduction 81 Urban proximity and development 81 Crime and anti-social behaviour 82 Wildlife 83 Pressures on farming and loss of traditional farming skills 84 Recreational pressure 85 Illegal recreational activity 87 Lack of knowledge and understanding 87 Climate change 88 Audience barriers 89 National/international economic downturn 90 A forgotten heritage and the loss of traditional skills 90 LPS implementation and sustainability 92 Consultations 93 Conclusions from risks and opportunities 93 Section 4 – Aims -

Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council, Arts

Draft Arts, Culture and Heritage Framework 2018-2023 Enriching lives through authentic and inspiring cultural opportunities for everyone June 2018 Prepared by: 1 Contents: Foreword from Lord Mayor Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council & Chair of the Economic Development and Regeneration Committee 1. Why do we need a framework? 2. The borough’s cultural landscape 3. Corporate agenda on the arts, culture and heritage 4. What the data tells us 5. What our stakeholders told us 6. Our vision 7. Guidelines for cultural programming 8. Outcomes, actions and milestones 9. Supporting activity 10. Impact 11. Conclusion 2 Foreword This Arts, Culture and Heritage Framework was commissioned by the Economic Development and Regeneration Committee of Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council. It sets the direction for cultural development in the borough for the next 5 years. The borough has an excellent cultural infrastructure to build upon and, as a new organisation, we have the opportunity to develop and improve access to quality arts, culture and heritage experiences for all our citizens and visitors. Community and Place are at the heart of all the council’s planning. We want our arts, culture and heritage services to serve the community and reflect the unique identity of this place. We have a strong track-record in arts, culture and heritage activity, providing a host of ways for people to become involved with venues, activities and events that enrich their lives and create a sense of community and well-being. We now have the opportunity to strengthen this offer by aligning our services and supporting partner organisations to ensure that arts, culture and heritage can have the optimum impact on the further development of the borough and its citizens. -

NAVAN FORT English Translation

NAVAN FORT English Translation NAVAN FORT Emain Macha County Armagh The Site Navan Fort is a large circular earthwork enclosure 2 miles W. of Armagh city. It stands on a hill of glacial clay over limestone, and though from a distance this hill is not very prominent, from the top the view on a clear day is impressive. To the NW. are the Sperrins; Slieve Gallion is to the N. and Slemish to NE., while to the S. are the uplands of mid Armagh. Clearly visible to the E. is Armagh city with its two hilltop cathedrals. Only to the W. is the view less extensive. The small lake called Loughnashade is close to the NE. of the fort, and the road which runs S. of the earthwork was probably already old when it was shown on a map made in 1602. Navan in Legend and History Navan can be firmly identified with Emain Macha, ancient capital of the kings of Ulster. In leg- end Macha was a princess or goddess, and one explanation for the name Emain Macha (twins of Macha) was that she gave birth to twins after winning a race against the king’s fastest chariot. Another story was that she traced the outline of the earthwork with the pin of her brooch. The important body of Early Irish legend known as the Ulster Cycle centres round King Concho- bor, who ruled his kingdom from Emain Macha. Here were great halls for feasting, for weapons and for the spoils of war, and here was the king’s warrior troop, the Red Branch Knights. -

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 30, 1938. Gagh, Corporation, Drumadd, Drumarg, TIRANNY BARONY

334 THE BELFAST GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 30, 1938. gagh, Corporation, Drumadd, Drumarg, TIRANNY BARONY. or Downs, Drumcote, Legarhil], Long- Eglish Parish (part of). stone, Lurgyvallen, Parkmore, or Demesne, .Tullyargle, Tullyelmer, Ballybrocky, Garvaghy, Lisbane, Lis- Tullylost, Tullymore, Tullvworgle, down, Tullyneagh, Tullysaran. Tyross, or Legagilly, Umgola. Clonfeacle Parish (part of). Ballytroddan, Creaghan. PORTADOWN PETTY SESSIONS Derrynoose Parish (part of). DISTRICT. Lisdrumbrughas, Maghery Kilcrany. Eglish Parish. (As constituted by an Order made on 5th August, 1938, under Section 10 of the Aughrafin, Ballaghy, Ballybrolly, Bally- Summary Jurisdiction and Criminal doo, Ballymartrim Etra, B'allymartrim Justice Act (N.L), 1935). Otra, Ballyscandal, Bracknagh, Clogh- fin, Creeveroe, Cullentragh, Drumbee, ONEILLAND, EAST, BARONY. Knockagraffy, Lisadian, Navan, Tam- laght, Terraskane, Tirgarriff, Tonnagh, Seagoe Parish (part of). Tray, Tullynichol. Ballydonaghy, Ballygargan, Ballyhan- Grange Parish (part of). non, Ballymacrandal, Ballynaghy, Bo- combra, Breagh, Carrick, Derryvore, Aghanore, Allistragh, Aughnacloy, Drumlisnagrilly, Drumnacanvy, Eden- Ballymackillmurry, Cabragh, Cargana- derry, Hacknahay, Kernan, Killyco- muck, Carrickaloughran, Carricktrod- main, Knock, Knocknamuckly, Levagh- dan, Drumcarn, Drumsill, Grangemore, ery, Lisnisky, Lylo, Seagoe, Lower; Killylyn, Lisdonwilly, Moneycree, Seagoe, Upper; Tarsan. Mullynure, Teeraw, Tullyard, TuIIy- garran. ONEILLAND, WEST, BARONY. Lisnadill Parish. Drumcree Parish (part of). Aghavilly, -

Official Report (Hansard)

Official Report (Hansard) Tuesday 24 January 2017 Volume 123, No 4 Session 2016-2017 Contents Speaker's Business……………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Assembly Business Public Accounts Committee ............................................................................................................... 1 Assembly Commission Membership ................................................................................................. 2 Assembly Members' Pension Scheme .............................................................................................. 2 Private Members' Business Cavity Insulation: NIHE Properties ................................................................................................... 2 Review of Bail Policy in Cases of Terrorism and Murder .................................................................. 17 Ministerial Code: Independent Investigation of Alleged Breaches ................................................... 34 Oral Answers to Questions Communities ...................................................................................................................................... 37 Economy ............................................................................................................................................ 46 Question for Urgent Oral Answer Health ................................................................................................................................................ 56 Ministerial Statement Public Inquiry on the Renewable Heat Incentive -

Free Entrance ONE WEEKEND OVER 400 PROPERTIES and EVENTS

Free Entrance ONE WEEKEND OVER 400 PROPERTIES AND EVENTS SATURDAY 13 & SUNDAY 14 SEPTEMBER www.discovernorthernireland.com/ehod EHOD 2014 Message from the Minister Welcome to European Heritage Open Days (EHOD) 2014 This year European Heritage Open Days will take place on the 13th Finally, I wish to use this opportunity to thank all and 14th September. Over 400 properties and events are opening of the owners and guardians of the properties who open their doors, and to the volunteers during the weekend FREE OF CHARGE. Not all of the events are in who give up their time to lead tours and host the brochure so for the widest choice and updates please visit our FREE events. Without your enthusiasm and website www.discovernorthernireland.com/ehod.aspx generosity this weekend event would not be possible. I am extremely grateful to all of you. In Europe, heritage and in particular cultural Once again EHOD will be merging cultural I hope that you have a great weekend. heritage is receiving new emphasis as a heritage with built heritage, to broaden our ‘strategic resource for a sustainable Europe’ 1. Our understanding of how our intangible heritage Mark H Durkan own local heritage, in all its expressions – built has shaped and influenced our historic Minister of the Environment and cultural – is part of us, and part of both the environment. This year, as well as many Arts appeal and the sustainable future of this part of and Culture events (p21), we have new Ireland and these islands. It is key to our partnerships with Craft NI (p7), and Food NI experience and identity, and key to sharing our (p16 & 17). -

1951 Census Armagh County Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF POPULATION OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1951 County of Armagh Printed & presented pursuant to 14 & 15 Geo. 6, Ch. 6 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1954 PRICE 7s M NET GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF POPULATION OF NORTHERN ffiELAND 1951 County of Armagh Printed & presented pursuant to 14 & 15 Geo. 6, Ch. 6 BELFAST ; HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1954 PREFACE Three censuses of population have been taken since the Governinent of Northern Ireland was established. The first enumeration took place in 1926 and incorporated questions relating to occupation and industry, orphanhood and infirmities. The second enumeration made in 1937 was of m^ore limited scope and was intended to bridge the gap between the census of 1926 and the census which it was proposed to take in 1941, but which had to be abandoned owing to the outbreak of war. The census taken as at mid night of 8th-9th April, 1951, forms the basis of this report and like that in 1926 questions were asked as to the occupations and industries of the population. The length of time required to process the data collected at an enumeration before it can be presented in the ultimate reports is necessarily considerable. In order to meet immediate requirements, however, two Preliminary Reports on the 1951 census were published. The first of these gave the population figures by administrative areas and towns and villages, and by Counties and County Boroughs according to religious profession. The Second Report, which was restricted to Counties and County Boroughs, gave the population by age groups. -

The World Has Become Smaller: Transport Through the Ages in Newry

The world has become smaller: transport through the ages in Newry and Mourne Motorised charabancs were a popular form of transport for outings in the Front cover: Sketch of Barkston Lodge in the townland of Carnmeen, 1910s and 1920s. This image shows such an outing in south Down c.1920. produced by Foster and Company of Dublin. Horses were the main mode Courtesy of Cathy Brooks of transport before the introduction of motorised vehicles in the early 20th century. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection Introduction This exhibition and accompanying booklet looks at aspects of transport in the Newry and Mourne area over the centuries. It begins by examining the importance of water transport in the Mesolithic period and how transport by land became more important in later prehistoric times. The influence of the establishment of churches and monasteries in the Early Christian period, and of political developments in the Middle Ages on the Bessbrook tram at Millvale crossroads in April 1940. formation of the road network is highlighted. The Photograph by W.A. Camwell from The Bessbrook and Newry Tramway (The Oakwood Press, 1979). exhibition also reveals how routeways established during these periods continue in use today. Travel by sea is seen as underpinning the growth of Newry as a wealthy mercantile centre in the 18th and 19th centuries. The impact of the arrival of the railways in the area in the mid 19th century, especially with regard to the emergence of Warrenpoint and Rostrevor as holiday destinations is stressed. The exhibition also explores how the introduction of motorised vehicles in the 20th century revolutionised transport for everyone.