The World Has Become Smaller: Transport Through the Ages in Newry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus School Newry Campus

2018/19 PROSPECTUS 2016-17 For: FocusPROSPECTUS School - Newry Campus Focus School Newry Campus FOCUS SCHOOL - NEWRY CAMPUS PROSPECTUS 2018/2019 CONTENTS Contents Page Introduction 3 School Details 4 Trust Details 6 Vision & Aims 7 Staff 8 Child Protection/Safeguarding Children 9 Charitable Fundraising 10 Curriculum 11 Special Educational Needs and Learning Support 14 About our School 15 Inspection Report 16 Policies and Rules 17 © Warrenpoint Education Trust 2 2018/2019 FOCUS SCHOOL - NEWRY CAMPUS PROSPECTUS Welcome to our school An introduction from the Trustees Dear Parent We would like to introduce you to our Focus School, Newry Campus. We are pleased to give you a copy of our School Prospectus, which contains information about our School. You are welcome to make an appointment to visit us at any time during the day to see the School in action. The Trustees and Head Teacher hope that this Prospectus will introduce you to the life and work of the School. Although we as Trustees have the responsibility for providing the Prospectus, it is the staff of the School, under the guiding hand of Mr McGreevy, our Head Teacher and Miss Smyth our Primary Lead, who do the important work of teaching the students. We know that the School is privileged to have such an excellent blend of experience and ideas in its teaching staff and some staff have been particularly pointed out as in the ‘leading edge’ category. We also recognise the commitment and teamwork from all support staff, helpers and also from parents. This Prospectus should provide you with all the information you need about the School, but if you do have any further questions please do not hesitate to contact the Head Teacher at the school address. -

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

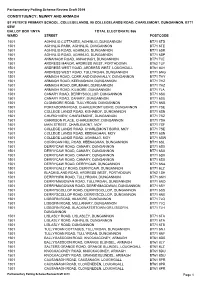

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

Canals Geography Primary Focus

B B C Northern Ireland Learning Primary Focus Teacher's Notes KS 2 Programme 9: Canals Geography ABOUT THE UNIT In this geography unit of four programmes, we cover our local linen and textiles industries, Northern Ireland canals and water management. The unit has cross curricular links with science. BROADCAST DATES BBC2 12.10-12.30PM Programme Title Broadcast Date 7 Geography - Textile Industry 10 March 2003 8 Geography - Linen 17 March 2003 9 Geography - Canals 24 March 2003 10 Geography - Water 31 March 2003 PROGRAMME - CANALS LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of the programme pupils should be able to • describe the development of our inland waterways • identify why canals fell into disuse • describe why canals are being restored • describe modern-day uses of canals ABOUT THE PROGRAMME Jamie Darling goes out and about in the Ulster countryside to discover our forgotten canals. The story begins in the old Tyrone coalfi elds and Jamie traces the development of our inland waterway system, which was designed to carry local coal to Dublin and Belfast. Some Key Stage 2 pupils show Jamie around the Newry Inland Canal and Ship Canal. We learn about the heyday of the canals and some of the problems that beset them. We learn how the advent of the railways sounded the death-knell of our canals as viable commercial routes. Jamie explores the remains of the old Lagan and Coalisland Canals and fi nds that a section of the Lagan Canal between Sprucefi eld and Moira now lies under the M1 Motorway. We see work in progress at the Island site in Lisburn where an old canal lock is being restored. -

MICHAEL J. MURPHY from : ‘Ulster Folk of Field and Fireside’

‘Moving slowly across the crest of a gentle hill, man, plough and Dusk was on Cloughinnea now, most mystical place of the valley. On horses are silhouetted against the evening sky. Th ey seem like shadowy one of its rocks a fairy thorn rose as if to beat the embers of a burnt- ghosts from a dim era that have returned as a quiet reminder to a out sky-line dropping behind it. Here the crimson knots of a cloud world crazed and dominated by speed.’ were turning purple; while further on, nearer Slieve Gullion, a roof and its chimney in bronze-edged silhouette dribbled smoke against a from : ‘At Slieve Gullion’s Foot’. brandy sky. A faint whisper of petal perfume sweetened the air; and as we rose to go, each corncrake sounded like the other’s echo.’ ‘From Dromintee at Slieve Gullion in South Armagh to Glenhull in from : ‘Mountain Year’ North Tyrone cannot be more than eighty miles; but when moving (Summer evening at Slieve Gullion). in Ireland to take up residence distance cannot be assessed in mere ‘Now the sun was coming through over Slieve-na-Bola, and it miles.’ made brassy rods in the stairs of cloud. Th e rods seemed to fi ll and sag, swinging to earth, to rock and fi eld, breaking on the high- from : ‘Tyrone Folk Quest’ fl ung houses of Th e Hip of Carnagore and the surrounds of dead bracken. It broke, too, on Glen Dhu and Balnamadda; and the ‘Th e cold was intense: winter had resharpened its claws of snow and sight was somehow like the sensation of the cry of blood to blood in was holding on. -

Tourism, Arts & Culture Report

Armagh City Banbridge & Craigavon Borough TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE REPORT AUGUST 2016 2 \\ ARMAGH CITY BANBRIDGE & CRAIGAVON BOROUGH INTRODUCTION The purpose of this document is to provide an overview of the topics relating to tourism, arts and culture in Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough to help inform the development of a community plan. KEY FINDINGS Population (2014) Total Population by Age Population 15% 22% 0-15 years 205,711 16-39 years 40-64 years 32% 65+ years 11% of total 32% NI population Tourism Overnight trips (2015) 3% 0.1m of overnight trips 22m trips in Northern Ireland spent Place of Origin Reason for Visit 5% 5% 8% Great Britain Business 18% 34% North America Other 43% Northern Ireland Visiting Friends & Relatives ROI & Other Holiday/Pleasure/Leisure 5% 11% Mainland Europe 69% 2013 - 2015 Accomodation (2015) 1,173 beds Room Occupancy Rates Hotels 531 55% Hotels Bed & Breakfasts, Guesthouses 308 and Guest Accomodation 25% Self Catering 213 Other Commercial Accomodation Hostel 121 TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE AUGUST 2016 // 3 Visitor Attractions (2015) Top three attractions 220,928visits 209,027visits 133,437visits Oxford Island National Kinnego Marina Lough Neagh Nature Reserve Discovery Centre Top three parks and gardens 140,074visits 139,435visits 126,123visits Edenvilla Park Tannaghmore Peatlands Park & Garden Gardens & Rare Breed Animal Farm Arts and Culture Engagement in Arts and Culture Arts Arts Used the public Visited a museum attendance participation library service or science centre Armagh City, Banbridge -

Barge 1 Lagan Waterway and History

LAGAN WATERWAY HISTORY Navigable waterways Prior to the advent of canals and railways in the 1700s and 1800s, packhorses and horses and carts or packhorse were the main means of moving stuff. Although Ireland has had a good road network since the 1600s, such roads were poorly surfaced and not always well maintained. The loads transported were thus limited by the hauling power of the horses and condition of the roads. Bulky, low-value goods such as coal, building materials and grain were particularly expensive to transport. Railways solved this problem, but only after the development of reliable steam locomotives in the mid-1800s. Before then, rivers were the cheapest way of moving large heavy loads where speed was not essential. Except for their tidal sections however, most rivers were not navigable for any great distance and the size of boats, and thus of the loads carried, was invariably limited by obstructions such as shallows, rapids and weirs. Navigations and canals Navigable waterways are of two types – navigations and canals. Navigations are existing natural watercourses whose navigability has been improved, whereas canals are entirely artificial channels excavated by hand and/or machine. The pros and cons of each type of waterway are as follows: For Against Navigations No major civil engineering works Prone to strong currents in winter and required so relatively cheap. lack of water in summer, both of which may make navigation temporarily impossible. [This was certainly the case on the Lagan] Summer water shortages are potentially exacerbated by demands of mill owners with prior rights to abstract water from the river. -

County Report

FOP vl)Ufi , NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE PRICE 85p NET NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE CONTENTS PART 1— EXPLANATORY NOTES AND DEFINITIONS Page Area (hectares) vi Population vi Dwellings vi Private households vii Rooms vii Tenure vii Household amenities viii Cars and garaging ....... viii Non-private establishments ix Usual address ix Age ix Birthplace ix Religion x Economic activity x Presentation conventions xi Administrative divisions xi PART II--TABLES Table Areas for which statistics Page No. Subject of Table are stated 1. Area, Buildings for Habitation and County 1 Population, 1971 2. Population, 1821-1971 ! County 1 3. Population 1966 and 1971, and Intercensal Administrative Areas 1 Changes 4. Acreage, Population, Buildings for Administrative Areas, Habitation and Households District Electoral Divisions 2 and Towns 5. Ages by Single Years, Sex and Marital County 7 Condition 6. Population under 25 years by Individual Administrative Areas 9 Years and 25 years and over by Quinquennial Groups, Sex and Marital Condition 7. Population by Sex, Marital Condition, Area Administrative Areas 18 of Enumeration, Birthplace and whether visitor to Northern Ireland 8. Religions Administrative Areas 22 9. Private dwellings by Type, Households, | Administrative Areas 23 Rooms and Population 10. Dwellings by Tenure and Rooms Administrative Areas 26 11. Private Households by Size, Rooms, Administrative Areas 30 Dwelling type and Population 12. -

Reinohl Collection Album List

Reinohl Collection album list The Reinohl Collection consists of 180 albums compiled by two brothers, Herbert and Albert Reinohl. The brothers were born in the late nineteenth century and began collecting material about transport (buses in particular) from childhood, continuing through to the 1950s. The collection is principally made up of tickets, but it also includes illustrations, press cuttings, journal articles and other ephemera from the UK and around the world. The list below gives brief details of what is covered by each album. If you would like to enquire about specific contents in the albums please contact us. The collection forms part of the Library collection at London Transport Museum (LTM) and is stored at the Museum Depot at Acton. Visits are available monthly, please check our website for further information https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/research/library. For all appointments, or any queries, please contact us. London Transport Museum Library Albany House, 98 Petty France, London SW1H 9EA Tel: +44 (0)343 222 5000 and select option 3 Email: [email protected] October 2019 1 Abbreviations used in the list: LGOC London General Omnibus Company LCC London County Council LPTB London Passenger Transport Board LT London Transport UDC Urban District Council Album Description 1 1829 London's First Omnibus to 1968 Woodruff's Omnibuses 2 Unknown Proprietors to James Powell 3 London & Suburban Omnibus Company to LGOC Route 14A 4 LGOC & Associate Companies Route 15 to LGOC & Thomas Tilling Ltd. Route 33A 5 LGOC & Thomas -

Michael Banfield Collection

The Michael Banfield Collection Friday 13 and Saturday 14 June 2014 Iden Grange, Staplehurst, Kent THE MICHAEL BANFIELD COLLECTION Friday 13 and Saturday 14 June 2014 Iden Grange, Staplehurst, Kent, TN12 0ET Viewing Please note that bids should be ENquIries Customer SErvices submitted no later than 16:00 on Monday to Saturday 08:00 - 18:00 Thursday 12 June 09:00 - 17:30 Motor Cars Thursday 12 June. Thereafter bids +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Friday 13 June from 09:00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 should be sent directly to the Saturday 14 June from 09:00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax Please call the Enquiries line Bonhams office at the sale venue. [email protected] when out of hours. +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax Sale times Automobilia Please see page 2 for bidder We regret that we are unable to Friday 13 June +44 (0) 8700 273 619 information including after-sale Automobilia Part 1 - 12 midday accept telephone bids for lots with collection and shipment a low estimate below £500. [email protected] Saturday 14 June Absentee bids will be accepted. Automobilia Part 2 - 10:30 Please see back of catalogue New bidders must also provide Motor Cars 15:00 (approx) for important notice to bidders proof of identity when submitting bids. Failure to do so may result Sale Number Illustrations in your bids not being processed. 22201 Front cover: Lot 1242 Back cover: Lot 1248 Live online bidding is CataloguE available for this sale £25.00 + p&p Please email [email protected] Entry by catalogue only admits with “Live bidding” in the subject two persons to the sale and view line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service Bids +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax To bid via the internet please visit www.bonhams.com Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. -

Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council, Arts

Draft Arts, Culture and Heritage Framework 2018-2023 Enriching lives through authentic and inspiring cultural opportunities for everyone June 2018 Prepared by: 1 Contents: Foreword from Lord Mayor Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council & Chair of the Economic Development and Regeneration Committee 1. Why do we need a framework? 2. The borough’s cultural landscape 3. Corporate agenda on the arts, culture and heritage 4. What the data tells us 5. What our stakeholders told us 6. Our vision 7. Guidelines for cultural programming 8. Outcomes, actions and milestones 9. Supporting activity 10. Impact 11. Conclusion 2 Foreword This Arts, Culture and Heritage Framework was commissioned by the Economic Development and Regeneration Committee of Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council. It sets the direction for cultural development in the borough for the next 5 years. The borough has an excellent cultural infrastructure to build upon and, as a new organisation, we have the opportunity to develop and improve access to quality arts, culture and heritage experiences for all our citizens and visitors. Community and Place are at the heart of all the council’s planning. We want our arts, culture and heritage services to serve the community and reflect the unique identity of this place. We have a strong track-record in arts, culture and heritage activity, providing a host of ways for people to become involved with venues, activities and events that enrich their lives and create a sense of community and well-being. We now have the opportunity to strengthen this offer by aligning our services and supporting partner organisations to ensure that arts, culture and heritage can have the optimum impact on the further development of the borough and its citizens. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Terrorism Knows No Borders

TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS October 2019 his is a special initiative for SEFF to be associated with, it is one part of a three part overall Project which includes; the production of a Book and DVD Twhich captures the testimonies and experiences of well over 20 innocent victims and survivors of terrorism from across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland. The Project title; ‘Terrorism knows NO Borders’ aptly illustrates the broader point that we are seeking to make through our involvement in this work, namely that in the context of Northern Ireland terrorism and criminal violence was not curtailed to Northern Ireland alone but rather that individuals, families and communities experienced its’ impacts across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and beyond these islands. This Memorial Quilt Project does not claim to represent the totality of lives lost across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland but rather seeks to provide some understanding of the sacrifices paid by communities, families and individuals who have been victimised by ‘Republican’ or ‘Loyalist’ terrorism. SEFF’s ethos means that we are not purely concerned with victims/survivors who live within south Fermanagh or indeed the broader County.