Integrating Policies for Ireland's Inland Waterways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Boyne Greenway and Navigation Restoration Frequently Asked Questions (Page 1 of 2)

The Boyne Greenway and Navigation Restoration Frequently Asked Questions (Page 1 of 2) What is the Boyne Greenway and Navigation Restoration? The Boyne Greenway and Navigation Restoration Scheme is proposed to consist of over 26km of a canal and riverside greenway from Navan to Oldbridge Drogheda via Slane and is proposed to incorporate the restoration of the Boyne Navigation. The Navigation Restoration would extend from the canal harbour in Navan to Oldbridge guard lock. The scheme would encourage physical activity, facilitate sustainable travel to work and school where possible and has the potential to be a flagship tourism scheme of regional, national and international significance. Who can use the scheme? Any non-motorized user will be able to enjoy the Boyne Greenway and will be able to travel the entire route. A key objective of the scheme is to ensure universal accessibility. This includes pedestrians, runners, cyclists of all experience, and wheelchair users (including powered wheelchairs and mobility scooters). Key aspects of the greenway that will help achieve this is that it will be mostly if not all off road and will have appropriate surface quality and width subject to localised physical restrictions. At what stage is the Boyne Greenway and Navigation Restoration project at? In terms of the greenway, the scheme is currently at route options development stage with a number of route options developed that will shortly be assessed in order to determine an emerging preferred route. The Navigation Restoration is currently at feasibility assessment stage. What is the purpose of this public consultation? The purpose of this public consultation process is to present the greenway route options that have been identified and to collect feedback through comments and completed questionnaires. -

HERITAGE PLAN 2016-2020 PHOTO: Eoghan Lynch BANKS of a CANAL by Seamus Heaney

HERITAGE PLAN 2016-2020 PHOTO: Eoghan Lynch BANKS OF A CANAL by Seamus Heaney Say ‘canal’ and there’s that final vowel Towing silence with it, slowing time To a walking pace, a path, a whitewashed gleam Of dwellings at the skyline. World stands still. The stunted concrete mocks the classical. Water says, ‘My place here is in dream, In quiet good standing. Like a sleeping stream, Come rain or sullen shine I’m peaceable.’ Stretched to the horizon, placid ploughland, The sky not truly bright or overcast: I know that clay, the damp and dirt of it, The coolth along the bank, the grassy zest Of verges, the path not narrow but still straight Where soul could mind itself or stray beyond. Poem Above © Copyright Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. Waterways Ireland would like to acknowledge and thank all the participants in the Heritage Plan Art and Photographic competition. The front cover of this Heritage Plan is comprised solely of entrants to this competition with many of the other entries used throughout the document. HERITAGEPLAN 2016-2020 HERITAGEPLAN 2016-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................4 Waterways Ireland ......................................................................................................................................6 Who are Waterways Ireland?................................................................................................................6 What -

Canals Geography Primary Focus

B B C Northern Ireland Learning Primary Focus Teacher's Notes KS 2 Programme 9: Canals Geography ABOUT THE UNIT In this geography unit of four programmes, we cover our local linen and textiles industries, Northern Ireland canals and water management. The unit has cross curricular links with science. BROADCAST DATES BBC2 12.10-12.30PM Programme Title Broadcast Date 7 Geography - Textile Industry 10 March 2003 8 Geography - Linen 17 March 2003 9 Geography - Canals 24 March 2003 10 Geography - Water 31 March 2003 PROGRAMME - CANALS LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of the programme pupils should be able to • describe the development of our inland waterways • identify why canals fell into disuse • describe why canals are being restored • describe modern-day uses of canals ABOUT THE PROGRAMME Jamie Darling goes out and about in the Ulster countryside to discover our forgotten canals. The story begins in the old Tyrone coalfi elds and Jamie traces the development of our inland waterway system, which was designed to carry local coal to Dublin and Belfast. Some Key Stage 2 pupils show Jamie around the Newry Inland Canal and Ship Canal. We learn about the heyday of the canals and some of the problems that beset them. We learn how the advent of the railways sounded the death-knell of our canals as viable commercial routes. Jamie explores the remains of the old Lagan and Coalisland Canals and fi nds that a section of the Lagan Canal between Sprucefi eld and Moira now lies under the M1 Motorway. We see work in progress at the Island site in Lisburn where an old canal lock is being restored. -

Inland Waterways Pavilion Breaks New Ground at BOOT Düsseldorf's

Inland Waterways International Inland Waterways International PRESS RELEASE Inland Waterways Pavilion breaks new ground at BOOT Düsseldorf’s 50th fair HALL 14 - STAND E22 19-27 JANUARY 2019 IWI Press Release, 06/02/2019 page 1 Inland Waterways International 50th BOOT, 19-27 JANUARY 2019 WI’S PARTICIPATION IN THE 50TH BOOT SHOW in itors would be charged extra. This, and the storage corri- Düsseldorf was highly successful, and proved that dors throughout the length of the pavilion, were much limited investment can be used to lever a massive appreciated by all. I overall effort and influence, benefiting all exhibitors, partners, sponsors and inland waterways in general. General context BOOT 2019 set a new record, with almost 2000 exhibi- tors from 73 countries and displays covering 220 000 m² of stand space. Nearly 250 000 water sports fans (247 000 visitors in 2018) came to Düsseldorf from over 100 countries, clear confirmation of the position BOOT holds as the leading event in the world. Foreign visitors were mostly from the Netherlands, Belgium, UK, Switzerland and Italy. Exhibitors reported great business and many BOOT director Petros Michelidakis (beside Peter Linssen) new contacts all over the world. Nearly 2000 journalists presents an anniversary cake to the IWP, at the start of the from 63 countries followed the event to report on trends Day of the Canals. On the left are BOOT Executive Director and innovations in the sector. Michael Degen and Junior Manager Max Dreckmann. IWI context The first Inland Waterways Pavilion was also highly successful for the relatively small family within the water recreation sector. -

Leitrim Council

Development Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 County / City Council GIS X GIS Y Acorn Wood Drumshanbo Road Leitrim Village Leitrim Acres Cove Carrick Road (Drumhalwy TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Aigean Croith Duncarbry Tullaghan Leitrim Allenbrook R208 Drumshanbo Leitrim 597522 810404 Bothar Tighernan Attirory Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim Bramble Hill Grovehill Mohill Leitrim Carraig Ard Lisnagat Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim 593955 800956 Carraig Breac Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Canal View Leitrim Village Leitrim 595793 804983 Cluain Oir Leitrim TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Cnoc An Iuir Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Cois Locha Calloughs Carrigallen Leitrim Cnoc Na Ri Mullaghnameely Fenagh Leitrim Corr A Bhile R280 Manorhamilton Road Killargue Leitrim 586279 831376 Corr Bui Ballinamore Road Aughnasheelin Leitrim Crannog Keshcarrigan TD Keshcarrigan Leitrim Cul Na Sraide Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Dun Carraig Ceibh Tullylannan TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Dun Na Bo Willowfield Road Ballinamore Leitrim Gleann Dara Tully Ballinamore Leitrim Glen Eoin N16 Enniskillen Road Manorhamilton Leitrim 589021 839300 Holland Drive Skreeny Manorhamilton Leitrim Lough Melvin Forest Park Kinlough TD Kinlough Leitrim Mac Oisin Place Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Mill View Park Mullyaster Newtowngore Leitrim Mountain View Drumshanbo Leitrim Oak Meadows Drumsna TD Drumsna Leitrim Oakfield Manor R280 Kinlough Leitrim 581272 855894 Plan Ref P00/631 Main Street Ballinamore Leitrim 612925 811602 Plan Ref P00/678 Derryhallagh TD Drumshanbo -

Chief Executive's Management Report

Chief Executive’s Management Report Fingal County Council Meeting Monday, September 10, 2018 Item No. 25 .ie 0 fingal CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S MANAGEMENT REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2018 Contents Economic, Enterprise and Tourism Development Environment and Water Services (EWS) Tourism Development (p.2) Environment (p.25) Events Climate Change Awareness Heritage Properties Refurbishment of Bottle Banks Cleaner Communities Local Enterprise Development (p.4) Reusable Cup Campaign Economic Development (p.5) River Basin Management Plans Balbriggan Strategy Balleally Landfill Projects LEADER Programme Litter Management Local Community Development Committee Enterprise Centres Water Services (p.26) Operations Operations (OPS) (p.7) Bike Parking Facilities Road Improvement Works Corporate Affairs and Governance (CAG) Street Lighting Corporate Affairs (p.27) Fleet Management and Plant Hire Unit Potential Presidential Candidates visit Traffic Management Chambers Irelands Awards Papal Event Benefacts.ie Launch NOAC Survey Smart Dublin SBIR Update Planning and Strategic Infrastructure (PSI) Planning Applications (p.11) Finan ce (p.30) Planning Decisions Financial Reports Building Control Preparation of the Swords Masterplan Balbriggan and Skerries skateparks Rathbeale Road upgrade Appendices Housing and Community (H&C) Housing (p.14) Pillars I-V Housing Supports Community (p.17) Arts (p.18) Sports (p.19) Libraries (p.20) 1 ECONOMIC, ENTERPRISE AND TOURISM DEVELOPMENT (EETD) Contents Tourism Development Economic Development Events Balbriggan Socio-Economic Strategy -

Barge 1 Lagan Waterway and History

LAGAN WATERWAY HISTORY Navigable waterways Prior to the advent of canals and railways in the 1700s and 1800s, packhorses and horses and carts or packhorse were the main means of moving stuff. Although Ireland has had a good road network since the 1600s, such roads were poorly surfaced and not always well maintained. The loads transported were thus limited by the hauling power of the horses and condition of the roads. Bulky, low-value goods such as coal, building materials and grain were particularly expensive to transport. Railways solved this problem, but only after the development of reliable steam locomotives in the mid-1800s. Before then, rivers were the cheapest way of moving large heavy loads where speed was not essential. Except for their tidal sections however, most rivers were not navigable for any great distance and the size of boats, and thus of the loads carried, was invariably limited by obstructions such as shallows, rapids and weirs. Navigations and canals Navigable waterways are of two types – navigations and canals. Navigations are existing natural watercourses whose navigability has been improved, whereas canals are entirely artificial channels excavated by hand and/or machine. The pros and cons of each type of waterway are as follows: For Against Navigations No major civil engineering works Prone to strong currents in winter and required so relatively cheap. lack of water in summer, both of which may make navigation temporarily impossible. [This was certainly the case on the Lagan] Summer water shortages are potentially exacerbated by demands of mill owners with prior rights to abstract water from the river. -

Waterways Ireland

Waterways Ireland Largest of the six North/South Implementation Bodies Statutory Function Manage, Maintain, Develop and Promote the Inland Navigable Waterways principally for Recreational Purposes 1,000 KM OF WATERWAY 420 KM OF TOWPATH SEVEN NAVIGATIONS 175 LOCKS & CHAMBERS 360 BRIDGES 1,200 HERITAGE STRUCTURES 13,900 M OF MOORINGS Our Goal ... - Deliver World Class Waterway Corridors & Increase Use - Create job, support business delivery - Sustain their unique built and natural heritage 3 Challenges • Declining Resources • Weather • Invasive Species • Aging & Historic Estate – infrastructure failure • Bye-Laws • Water Quality & Supply • Designated Lands How Have We Responded to these Challenges? Used capital funding for repairs and replacement New embankment constructed in Cloonlara Lock gate Manufacture & Replacement: Installation at Roosky Lock Embankment repair completed in Feb '18 along the Lough Allen canal Reduce Costs • Fixed overheads reduced by 50% from 2013 • Seasonal business – staff nos: 319 • Reduced Senior Management Team • Use of technology – internet to carry calls - €100k per annum • Match service to use – Lockkeepers Agreement - €180k per annum • Closed services in Winter Earn Income • Goal to earn ongoing income stream on each waterway • Operating licences - €100k • Develop towpaths, ducting to carry services - €86k per annum • Charge 3rd parties for temporary use of our land, eg site office, 3 car parking spaces €24.5k per annum • Sell airspace, eg Grand Canal Dock - €1.5m • Rent land and buildings - €160k • Let office space in HQ - €45k each year Use 3rd Party Funding to Support Development • Royal Canal Towpath Development - €3.73 m – Dept of Tourism & Sport and Local Authority funding Fáilte Ireland Strategic Partnership 75% funded Key project development; - Shannon Masterplan - Dublin City Canals Greenway - Tourism Masterplan for Grand Canal Dock • Shannon Blueway Acres Lake Boardwalk - €500k – Rural Recreation Scheme Goal .. -

A Preliminary Report on Areas of Scientific Interest in County Offaly

An Foras CONSERVATION AND AMENITY Forbartha ADVISORY SERVICE Teoranta The National Institute for Physical Planning and Construction Research PRELIMINARY REPORT ON AREAS OF SCIENTIFIC INTEREST IN n C)TTNTY C)FFAT V L ig i6 n Lynne Farrell December, 1972 i n Teach hairttn Bothar Waterloo Ath Cllath 4 Telefan 6 4211 St. Martin's House Waterloo Road Dublin 4 J J 7 7 Li An Foras CONSERVATION AND AMENITY Forbartha ADVISORY SERVICE Teoranta The National Institute for Physical Planning and 7 Construction J Research PRELIMINARY REPORT ON AREAS OF SCIENTIFIC INTEREST IN COTTNTY (FFAT.Y 11 Lynne Farrell December, 1972 7 Li i s Teachhairtin J Bother Waterloo Ath Math 4 Teiefcn 64211 St. Martin's House Waterloo Road Dublin 4 w 7 LJ CONTENTS SECTION PAGE NO. Preface 1 B Vulnerability of Habitats 3. C General Introduction 6. D Explanation of Criteria Used in 9. Rating Areas and Deciding on Their Priority E Table Summarising the Sites 11. Visited J Detailed Reports on the Sites 16. Table Summarising the Priority of 119. the Sites and Recommendations for Their Protection J 7 U FOREWORD L1 7 jJ This report is based on data abstracted from the filesof the Conservation and Amenity Advisory Section, Planning Division, An Foras Forbartha; from J published and unpublished sources; and from several periods of fieldwork undertaken during August 1971 and September - November 1972.It is a J preliminary survey upon which, it is hoped, further research willbe based. The help of Miss Scannell of the National Herbarium, FatherMoore of U.C.D. Botany Department, Dr. -

Inland Waterways: Romantic Notion Or Means to Kick-Start World Economy? by Karel Vereycken

Inland Waterways: Romantic Notion or Means To Kick-Start World Economy? by Karel Vereycken PARIS, Sept. 24—Some 300 enthusiasts of 14 nations, dominated most of the sessions—starts from the dan- among them, the USA, France, Belgium, Netherlands, gerous illusion of a post-industrial society, centered Germany, China, Serbia, Canada, Italy, and Sweden), on a leisure- and service-based economy. For this gathered in Toulouse Sept. 16-19, for the 26th World vision, the future of inland waterways comes down to Canals Conference (WCC2013). The event was orga- a hypothetical potential income from tourism. Many nized by the city of Toulouse and the Communes of the reports and studies indicate in great detail how for- Canal des Deux Mers under the aegis of Inland Water- merly industrial city centers can become recreational ways International (IWI). locations where people can be entertained and make Political officials, mariners, public and private indi- money. viduals, specialists and amateurs, all came to share a Radically opposing this Romanticism, historians single passion—to promote, develop, live, and preserve demonstrated the crucial role played by canals in orga- the world heritage of waterways, be they constructed by nizing the harmonic development of territories and the man and nature, or by nature alone. birth of great nations. Several Chinese researchers, no- For Toulouse, a major city whose image is strongly tably Xingming Zhong of the University of Qingdao, connected with rugby and the space industry, it was an and Wang Yi of the Chinese Cultural Heritage Acad- occasion to remind the world about the existence of the emy showed how the Grand Canal, a nearly 1,800-km- Canal du Midi, built between 1666 and 1685 by Pierre- long canal connecting the five major rivers in China, Paul Riquet under Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French Fi- whose construction started as early as 600 B.C., played nance Minister for Louis XIV. -

Locks and Bridges on Ireland's Inland Waterways an Abundance of Fixed

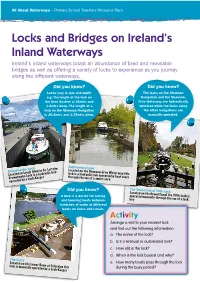

ack eachers Resource P ways – Primary School T All About Water Locks and Bridges on Ireland’s Inland Waterways Ireland’s inland waterways boast an abundance of fixed and moveable bridges as well as offering a variety of locks to experience as you journey along the different waterways. Did you know? Did you know? The locks on the Shannon Navigation and the Shannon- Locks vary in size and depth Erne Waterway are hydraulically e.g. the length of the lock on operated while the locks along the Erne System is 36mtrs and the other navigations are 1.2mtrs deep. The length of a manually operated. lock on the Shannon Navigation is 29.2mtrs and 1.35mtrs deep. Ballinamore Lock im aterway this Lock . Leitr Located on the Shannon-Erne W n in Co ck raulic lock operated by boat users gh Alle ulic lo lock is a hyd Drumshanbon Lou ydra ugh the use of a smart card cated o ock is a h thro Lo anbo L eeper rumsh ock-K D ed by a L operat The Grand Canal 30th Lock Did you know? Located on the Grand Canal the 30th Lock is operated manually through the use of a lock A lock is a device for raising key and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on rivers and canals. Activity Arrange a visit to your nearest lock and find out the following information: a. The name of the lock? b. Is it a manual or automated lock? c. How old is the lock? d. -

World Canals Conference in Ghent

27th World Canals Conference in Ghent 7-10 September 2015 ABSTRACT BOOK 27th World Canals Conference 7-10 September 2015 Ghent, Belgium Abstract Book TABLE OF CONTENTS Theme 1: Waterways in International Perspective The importance of the Ghent waterways in the past and in the future ……… 5 The Seine-Scheldt project …………..................................................................... 6 Unique location of port of Ghent does not only attract thousands of inland vessels but also hundreds of inland cruises ……..............….. 7 The river Lys, international cooperation …………............................................. 8 The Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine (CCNR) …................... 11 Inland waterways development in Wallonia within a European perspective ..............................................................................................… 12 Why and how to keep small canal waters alive. For example in the Netherlands. And how to reuse them …................................................… 13 Globalising the Kelpies ………….................................................................…… 15 The port of Terneuzen in relation to the port of Ghent ……………..............… 17 Germany's new Inland Waterway network bridging East and West……......… 18 Theme 2: Waterways in economical perspective Innovation in the service of conservation : ensuring the sustainability of Parks Canada’s historic canals by revenue generation …….........… 20 A Renewed Era in Development along the Erie Canal ……........................… 23 Optimizing