Migration Letters, Volume: 12, No: 3, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

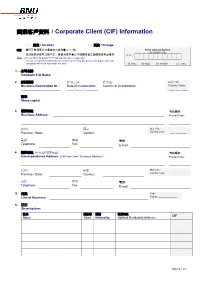

Customer Name

商業客戶資料 / Corporate Client (CIF) Information □ 開立 / Creation □ 更改 / Change 注意: - 請用正楷填寫並在適當的方格內劃上“”號。 PARA USO DO BANCO FOR BANK USE 如所提供作答的空間不足,請使用附有貴公司機構名稱之信函提供有關資料。 C.I.F.: Note : - Please fill in BLOCK LETTERS and tick where applicable In case the space provided for any answer is not enough, please use paper with your company letterhead to provide the data 日期 Date:___ (日 day) ____ (月 month) ______ (年 year) 1. – 公司名稱: Company Full Name: 2. 註冊號碼: 註冊日期: 註冊地: 國家代碼 Business Registration Nr. : Date of Incorporation: Country of Incorporation: Country Code: _______________________ ____ /____ / ________ ___ ___ ___ 資本: Share capital ____________________________ 3. 營業地址: 郵政編號: Business Address: Postal Code: 省/州: 國家 國家代碼 Province / State: Country: Country Code: ___ ___ ___ 電話: 傳真 電郵 Telephone Fax: E-mail: 4. 通訊地址: (若有異於營業地址) 郵政編號: Correspondence Address: (if different from “Business Address”) Postal Code: 省/州: 國家 國家代碼 Province / State: Country: Country Code: ___ ___ ___ 電話: 傳真 電郵 Telephone Fax: E-mail: 5. 行業: Code: Line of Business: Código ___________ 6. 股東 Shareholders 姓名: 持股權 國籍 常居地址: CIF Name: Share Nationality: Habitual Residential Address: Page 頁 1 of 4 7. 董事會成員及有效簽署人: Directors & Authorized Signatories: 姓名: 職位 國籍 常居地: CIF Name: /Title Nationality: Habitual Residential Address: 8. 持有其他公司股權 (如有) Shareholdings in other companies – if applicable 公司名稱: Company Full Name: 註冊地址 Registered Address: 註冊日期 持股金額 持股量 Date of incorporation Share Capital Capital _________________________________________________ ____ / ____ / _________ ___________________ _______ _________________________________________________ 公司名稱: Company Full Name: 註冊地址 Registered Address: 註冊日期 持股金額 所佔率% Date of incorporation Share Capital Capital _________________________________________________ ____ / ____ / _________ ___________________ _______ _________________________________________________ 9. 擁有之不動產(如有): Real Estate owned by the Company – if applicable 註冊地址: 地點: 市值: 負擔(抵押 / 按揭) Description/Registration details: Location: Value: Pledge / Mortgage: Page 頁 2 of 4 10. -

China: Procedure and Requirements to Obtain a Biometric Passport

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 3 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home > Research Program > Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) respond to focused Requests for Information that are submitted to the Research Directorate in the course of the refugee protection determination process. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIRs. Earlier RIRs may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. 6 May 2013 CHN104415.E China: Procedure and requirements to obtain a biometric passport, including date they started to be issued; indicators that the passport is biometric, including symbols Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Date of First Issue for Biometric Passports Sources indicate that China began to issue biometric passports on 15 May 2012 (China 16 May 2012; Dalian Municipal Government 17 May 2012). The identity-document checking service operated by Keesing Reference Systems writes that a passport that "contains a contactless chip in the back cover" was first issued in February 2012 (n.d.a). According to the official web portal of the Chinese government, traditional passports may continue to be used for as long as they are valid (China 16 May 2012). People's Daily Online, a Chinese news website founded in 1997 (People's Daily Online n.d.), reports that electronic passports for public affairs were first issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 1 July 2011 (5 July 2011). These passports contain a "'component layer,' consisting of microchips, electronic circuits, and other parts" inside the back cover, which includes "the passport owner's name, sex and personal photo as well as the passport's term of validity and [the] digital certificate of the chip" (ibid.). -

Criminal Background Check Procedures

Shaping the future of international education New Edition Criminal Background Check Procedures CIS in collaboration with other agencies has formed an International Task Force on Child Protection chaired by CIS Executive Director, Jane Larsson, in order to apply our collective resources, expertise, and partnerships to help international school communities address child protection challenges. Member Organisations of the Task Force: • Council of International Schools • Council of British International Schools • Academy of International School Heads • U.S. Department of State, Office of Overseas Schools • Association for the Advancement of International Education • International Schools Services • ECIS CIS is the leader in requiring police background check documentation for Educator and Leadership Candidates as part of the overall effort to ensure effective screening. Please obtain a current police background check from your current country of employment/residence as well as appropriate documentation from any previous country/countries in which you have worked. It is ultimately a school’s responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate police background documentation for their Educators and CIS is committed to supporting them in this endeavour. It is important to demonstrate a willingness and effort to meet the requirement and obtain all of the paperwork that is realistically possible. This document is the result of extensive research into governmental, law enforcement and embassy websites. We have tried to ensure where possible that the information has been obtained from official channels and to provide links to these sources. CIS requests your help in maintaining an accurate and useful resource; if you find any information to be incorrect or out of date, please contact us at: [email protected]. -

Smarter Aadhaar Card for a Smarter and Meticulous India

PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) Smarter Aadhaar Card For A Smarter And Meticulous India Dr. Samson. R. Victor1, Candida Grace Dsilva N2, Pooja Tiwari 3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Education, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak (M.P.) India 2Teacher, National Public School, Bangalore, India 3Research Scholar, Department of Linguistics and Contrastive Study of Tribal Languages, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak (M.P.) India Email: [email protected], [email protected] ,[email protected] Dr. Samson. R. Victor, Candida Grace Dsilva N, Pooja Tiwari: Smarter Aadhaar Card For A Smarter And Meticulous India -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: India - Unique identification number, UIDAI, Aadhaar card & a smart card ABSTRACT The Unique Identification Number (UIDAI) – Aadhaar, is a unique number that is derived to identify every citizen of India, including the Non Residential Indians (NRI). This document was introduced to serve as an authentic identity proof for individuals. UIDAI is a secure document which consists of iris scan and fingerprint scan, that is person specific and identity theft is not very easy, making it a robust and versatile document.Exploring the robustness and versatility of this document this paper focuses on venturing out to identify the diverse applicability of the UIDAI to benefit both the government and the Indian citizens. In order to widen the scope of Aadhaar card, this paper proposes to use the Aadhaar card number to collect and store data such as demographic, health, education, employment, financial, police records of every resident of India so that the government can utilise the information, in order to monitor, analyse and frame policies and schemes in the field of education, employment,pension, scholarship, health schemes, dole, subsidiaries to farmers 10085 PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) and low income people,in order to up-lift the beneficiaries thus helping India to become a developed country. -

Guidebook for Entry for Training in Hong Kong

Immigration Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region ************************ Guidebook for Entry for Training in Hong Kong ID(E) 993 (5/2020) CONTENTS Paragraphs I. Introduction 1-2 II. Eligibility Criteria 3 III. Application Procedures 4-6 IV. Travel Documentation Requirement 7-8 V. Entry of Dependants 9-11 VI. Other Information 12-20 VII. Checklist of Forms and Documents to be Submitted I. Introduction This guidebook sets out the entry arrangements for persons who wish to enter the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) for training. 2. This entry arrangement does not apply to: (a) nationals of Afghanistan, Cuba, Laos, Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of) and Nepal; and (b) Chinese residents of the Mainland (other than Mainland employees and business associates of well-established and multi-national companies based in Hong Kong). II. Eligibility Criteria 3. An application for a visa/entry permit to enter the HKSAR for a limited period (not more than 12 months) of training to acquire special skills and knowledge not available in the applicant’s country/territory of domicile may be favourably considered if: (a) there is no security objection and no known record of serious crime in respect of the applicant; (b) the bona fides of the applicant and the sponsoring company are satisfied; (c) the sponsoring company is a well-established company, capable of providing the proposed training; (d) there is a contract signed between the sponsoring company and the applicant; (e) the sponsoring company guarantees in writing the maintenance and repatriation of the applicant and that the applicant will receive training in the sponsor’s premises until the end of the agreed period, after which the applicant will return to his/her place of residence; and (f) the proposed duration and content of the training programme can be justified. -

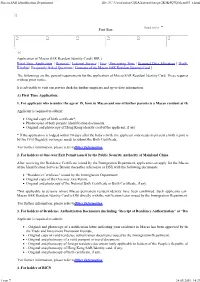

Macau SAR Identification Department File:///C:/Users/Palop.GIGA/Zotero/Storage/2K5K4Q7Q/Idcard03 E.Html

Macau SAR Identification Department file:///C:/Users/palop.GIGA/Zotero/storage/2K5K4Q7Q/idcard03_e.html Sound Assist: Font Size: Application of Macao SAR Resident Identity Card ( BIR ) [First Time Application | Renewal | External Service | Fees | Processing Time | Personal Data Alteration | Death Kinship | Frequently Asked Questions | Contents of the Macao SAR Resident Identity Card ] The followings are the general requirements for the application of Macao SAR Resident Identity Card. These requirem without prior notice. It is advisable to visit our service desk for further enquiries and up-to-date information. A) First Time Application: 1. For applicant who is under the age of 18, born in Macao and one of his/her parents is a Macao resident at the Applicant is required to submit: Original copy of birth certificate*; Photocopies of both parents' identification documents; Original and photocopy of Hong Kong identity card of the applicant, if any * If the application is lodged within 90 days after the baby’s birth, the applicant only needs to present a birth report (s by the Civil Registry, no longer needs to submit the Birth Certificate. ¨For further information, please refer toOther Information. 2. For holders of One-way Exit Permit issued by the Public Security Authority of Mainland China After receiving the Residence Certificate issued by the Immigration Department, applicants can apply for the Macao at the Identification Services Bureau (hereafter referred to as DSI) with the following documents: "Residence Certificate" issued by the Immigration Department; Original copy of the One-way Exit Permit; Original and photocopy of the Notarial Birth Certificate or Birth Certificate, if any. -

Country Advice

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN33347 Country: China Date: 16 May 2008 Keywords: China – CHN33347 – Establishing a Business– Identity Cards – Residence Cards – Hukou – Shenzhen This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please advise whether it is possible to set up a company using another person’s identity and personal information in the PRC? 2. Please advise whether it is possible to use another person’s identification card to find a place to live in the PRC? Would a person be able to exist, operate a business and pay taxes without using his identity card? RESPONSE 1. Please advise whether it is possible to set up a company using another person’s identity and personal information in the PRC? No specific information or examples were located in the sources consulted regarding persons setting up companies in China using another person‘s identity or personal information. A review of source information relevant to the question of the ability of a person to establish a business in China using false or fraudulently obtained identity documentation is presented below under the following sub-headings: Procedures and Documentation for Establishing a Business in China, and Fake Identity Documents in China. -

E038-48 23/03/2021 Questions & Answers [ Certificate of Entitlement

Questions & Answers [ Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode | Macao SAR Resident Identity Card | Macao SAR Travel Documents | Nationality Application |Certificate of Criminal Record | Kinship Verification |Others ] Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode 1. How many working days does it take to process the “Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode”? Ans: The processing time is 30 working days after the day on which this bureau has received all required documents from the applicant (exclusive of the day of receipt of required documents). 2. If my application for the “Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode” is approved, when should I come to Identification Services Bureau to apply for the Macao SAR Resident Identity Card? Ans: Applicants are advised to collect the “Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode” within six months from the date of issuance, and lodge the application of the Macao SAR Resident Identity card as soon as possible. Macao SAR Resident Identity Card 1. Under what circumstances do cardholders need to replace their Macao SAR Resident Identity Card? Ans: A) Macao SAR Resident Identity Card expired (ID card can be renewed 6 months prior to the expiration date. For applicants holding a contact-based electronic Macao SAR Resident Identity Card with permanent validity, they can replace their identity card if needed; B) Changes of personal information, such as first and last name, parents’ name, date of birth or place of birth; C) Status changed from Non-Permanent Resident to Permanent Resident D) Damage or loss Besides aforesaid circumstances, applicants can submit a request for replacement to the Director of the Identification Services Bureau for approval with other appropriate reasons. -

Document Types Supported by Assureid™ V4.4.4260.0 Legend

Document Types Supported by AssureID™ V4.4.4260.0 Copyright © 2016 - AssureTec Technologies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Summary Total ICAO Non-ICAO North American Driver's Licenses 967 0 967 North American Identification Documents 425 6 419 International Driver's Licenses 387 0 387 International Identification Documents 425 39 386 Passports 743 604 139 Visas 59 49 10 Travel Documents and Permits 83 50 33 Other 103 1 102 Total Supported Documents 3192 749 2443 Legend Term Meaning Issuer The government jurisdiction that issued the document. This could be a country, state, province, or other government jurisdiction The full descriptive name of the document type. The name typically includes issuer (e.g. France), issuer abbreviation (e.g. FRA), document Document Type class (e.g. driver’s license or passport), and type of issue (e.g. commercial driver’s license, under 21, learner’s permit, etc.) Jurisdictions release new versions of documents regularly. The Series is a label that has been assigned by AssureTec to uniquely identify Series each version of the document (also known as series or issue). Typically the Series represents the first year that the document version was released, but that is not always the case The physical size of the document. ID1 represents a card-sized document such as a driver’s license or identification card. ID3 represents a Size passport-sized document Certain editions of AssureID only include a subset of the global document library, which is divided into four geographic regions: NA=North Region America, SA=South America, EMEA=Europe, Middle East, and Africa, and APAC=Asia-Pacific. -

Thematisch Ambtsbericht Oeigoeren in China 2014-2015

Thematisch ambtsbericht Oeigoeren in China 2014-2015 Datum maart 2016 Pagina 1 van 57 Thematisch ambtsbericht Oeigoeren in China 2014-2015 Colofon Plaats Den Haag Opgesteld door Directie Azië en Oceanië Pagina 2 van 57 Thematisch ambtsbericht Oeigoeren in China 2015 Inleiding_____________________________________________________5 1. Algemene gegevens___________________________________6 1.1 Algemeen _________________________________________________6 1.2 Cultuur en talen __________________________________________6 1.3 Onderwijs _________________________________________________7 2. Politieke ontwikkelingen _____________________________8 2.1 Aanpak van terrorisme___________________________________8 2.1.1 2014-Antiterrorismecampagne _______________________________ 9 2.1.2 2015-Nieuwe veiligheidswetten _____________________________ 10 2.2 Spiraal van geweld ______________________________________12 3. Veiligheidssituatie ___________________________________14 3.1 Algemeen ________________________________________________14 3.1.1 Economische ontwikkeling _____________________________________ 14 3.2 Geweldsincidenten in Xinjiang _________________________16 3.2.1 Incidenten in 2014__________________________________________ 16 3.2.2 Incidenten in 2015__________________________________________ 21 3.3 Geweldsincidenten in overige provincies in China.____24 2014____________________________________________________________24 3.4 Geweldsincidenten buiten China _______________________25 4. Mensenrechten _______________________________________25 4.1 Algemeen -

Digital Identities Advancing Digital Societies in Asia Pacific

Digital identities Advancing digital societies in Asia Pacific Copyright © 2018 GSM Association GSMA Intelligence The GSMA represents the interests of mobile GSMA Intelligence is the definitive source of global operators worldwide, uniting nearly 800 operators mobile operator data, analysis and forecasts, and with more than 300 companies in the broader publisher of authoritative industry reports and mobile ecosystem, including handset and device research. Our data covers every operator group, makers, software companies, equipment providers network and MVNO in every country worldwide and internet companies, as well as organisations – from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. It is the most in adjacent industry sectors. The GSMA also accurate and complete set of industry metrics produces industry-leading events such as Mobile available, comprising tens of millions of individual World Congress, Mobile World Congress Shanghai, data points, updated daily. Mobile World Congress Americas and the Mobile GSMA Intelligence is relied on by leading 360 Series of conferences. operators, vendors, regulators, financial For more information, please visit the GSMA institutions and third-party industry players, to corporate website at www.gsma.com support strategic decision making and long- term investment planning. The data is used as an Follow the GSMA on Twitter: @GSMA industry reference point and is frequently cited by the media and by the industry itself. Our team of analysts and experts produce regular thought-leading research reports across a range of industry topics. www.gsmaintelligence.com [email protected] This report was authored by TRPC is a research consultancy with over 25 James Robinson, Senior Analyst years’ experience in the telecommunications and Barbara Arese Lucini, Senior Analyst information technology industries in the Asia-Pacific Jeanette Whyte, Senior Policy Manager – APAC region. -

Identity Document from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Identity document From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from ID card) "National identity card" redirects here. For cards referred to in the English language as "national identity card", see: National identity card (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.(January 2008) An identity document (also called a piece of identification or ID) is any document which may be used to verify aspects of a person's Personalidentity. If issued in the form of a small, mostly standard-sized card, it is usually called an identity card (IC). In some countries the possession of a government-produced identity card is compulsory while in others it may be voluntary. In countries which do not have formal identity documents, informal ones may in some circumstances be required. In the absence of a formal identity document, some countries accept driving licences as the most effective method of proof of identity. Most countries accept passports as a form of identification. Contents [hide] 1 Information included in ID documents 2 Adoption of identity cards o 2.1 Arguments for o 2.2 Arguments against 3 National policies o 3.1 European Union . 3.1.1 Belgium . 3.1.2 Bulgaria . 3.1.3 Cyprus . 3.1.4 Czech Republic . 3.1.5 Denmark . 3.1.6 Estonia . 3.1.7 Finland . 3.1.8 France . 3.1.9 Germany . 3.1.10 Greece . 3.1.11 Hungary . 3.1.12 Italy . 3.1.13 Poland . 3.1.14 Portugal .