TOCC0427DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Catalogue 2006 Catalogue Complete

COMPLETE CATALOGUE 2006 COMPLETE CATALOGUE Inhalt ORFEO A – Z............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Recital............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................82 Anthologie ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................89 Weihnachten ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................96 ORFEO D’OR Bayerische Staatsoper Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................99 Bayreuther Festspiele Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................109 -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

JUNE 2014 LIST See Inside for Valid Dates

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 JUNE 2014 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer, 11th June sees the 150th anniversary of the birth of Richard Strauss and we have already seen a good sprinkling of new releases and re-issues appear in celebration this year. Thielemann’s new Elektra for DG is probably the highest-profile release this month, featuring a magnificent cast that includes Rene Pape and Anne Schwanewilms. Sadly, we hadn’t yet managed to obtain a preview copy at the time of going to print, but it certainly looks very promising! DG are also issuing a deluxe LP-sized boxset of Karajan’s analogue Strauss recordings this month that will feature 11 CDs, plus the entire contents on a single Blu-ray Audio. As is the trend at the moment, it will be a limited edition set packed full of extra material including photos and original liner notes. See p.2 for more information. Continuing with the Strauss theme, you may also like to take a look at the listing we have compiled of recordings from various independent labels. This covers 3½ pages (pp.10-13) and features some truly great titles. A good opportunity to fill in gaps in the library! Away from Strauss, other things to point out are a further batch of Most Wanted Recitals from Decca, featuring wonderful discs from the likes of Siepi, Nilsson, Souzay, Carreras etc. Harmonia Mundi are issuing another 10 titles in their HM Gold series - top recordings moved from their full-price catalogue down to mid-price. -

The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years Of

Press release | 30/3/2017 | acr | Updated: July 2017 The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years of the Future of Opera 10 premieres for this major birthday, two of which are reencounters with titles of legendary Felsenstein productions, two are world premieres and four are operatic milestones of the 20 th century. 70 years ago, Walter Felsenstein founded the Komische Oper as a place where musical theatre makers were not content to rest on the laurels of opera’s rich traditions, but continually questioned it in terms of its relevance and sustainability. In our 2017/18 anniversary season, together with their team, our Intendant and Chefregisseur Barrie Kosky and the Managing Director Susanne Moser are putting this aim into practice once again by way of a diverse program – with special highlights to celebrate our 70 th birthday. From Baroque opera to operettas and musicals, the musical milestones of 20 th century operatic works, right through to new premieres of operas for children, with works by Georg Friedrich Handel through to Philip Glass, from Jacques Offenbach to Jerry Bock, from Claude Debussy to Dmitri Shostakovich, staged both by some of the most distinguished directors of our time as well as directorial newcomers. New Productions Our 70 th birthday will be celebrated not just with a huge birthday cake on 3 December, but also with two anniversary productions. Two works which enjoyed great success as legendary Felsenstein productions are returning in new productions. Barrie Kosky is staging Jerry Brock’s musical Fiddler on the Roof , with Max Hopp/Markus John and Dagmar Manzel in the lead roles, and the magician of the theatre, Stefan Herheim, will present Jacques Offenbach’s operetta Barbe- bleue in a new, German and French version. -

Ria Us a T Q .Com Mn

buchantiquariat Internet: http://comenius-antiquariat.com 43462 • Amstutz-Kunz, Frieda, Gedichte. [Bern ca 1960]. 61 S. kart. CHF 12 / EUR 10.20 Datenbank: http://buch.ac 125396 • Andersen, Hans Christian, Hanhart, Brigitte, Die Schneekönigin. Ein Märchen. Mönchaltorf, A Q Wochenlisten: http://buchantiquariat.com/woche/ Kataloge: http://antiquariatskatalog.com Hamburg: Nord-Süd-Verlag, 1987. [26] Seiten mit Abbildungen. Pappband (gebunden). 4to. CHF 18 / A RI AGB: http://comenius-antiquariat.com/AGB.php EUR 15.30 • Ein Nord-Süd Märchenbuch. - Erzählt von Brigitte Hanhart. Mit Bildern von Bernadette .COM M N US . T com 65373 • Andrade, Jorge Carrera, Poemas/Gedichte. Stuttgart: Klett/Cotta 1980. 222 S. Ppbd m.U. CHF 28 / EUR 23.80 • Spanisch/Deutsch. Übertragung und Nachwort von Fritz Vogelsang. 112434 • Anet, Daniel, Ce qui me chante. 2e éd. Martigny: H. Anet, 1996. 78 Seiten mit Abbildungen. Kartoniert. Katalog Literatur div. CHF 15 / EUR 12.75 • Quatre dessins de l'auteur. 108617 • [Anonym] Lettres amoureuses d'un frère a son élève. Alexandrie [Brüssel]: • Staatsstrasse 31 • CH-3652 Hilterfingen Durando, [ca. 1875]. 221 Seiten. Halblederband auf 5 Bünden mit Rückenschildchen. Fax 033 243 01 68 • E-Mail: [email protected] Einzeltitel im Internet abrufen: http://buch.ac/?Titel=[Best.Nr.] Kleinoktav. CHF 150 / EUR 127.50 • Nummer 234 von 500 Exemplaren. - Einbandkanten Stand: 19/08/2012 • 2739 Titel stark berieben, hintere Rückenkante auf der ganzen Länge aufgeplatzt, Papier leicht gebräunt, vereinzelte Flecken, Exlibris auf Innendeckel, auf Seite 38 ist ein griechischer Textabschnitt auf französisch übersetzt und handschriftlich zwischen die Zeilen eingefügt. 120771 • Achmatova, Anna, Gedichte. Russisch und deutsch. 1. Auflage. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 110226 • Anthoine de la Sale, Die fünfzehn Freuden der Ehe. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

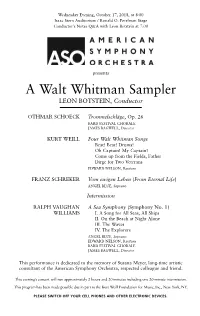

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Emil Hadina (1885-1957) Zum Literarischen Leben in Der Provinz

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA DISERTACN͡ PRÁCE Emil Hadina (1885-1957) Zum literarischen Leben in der Provinz AUTOR PRÁCE PhDr. ZdenˇekMareˇcek VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE Prof. PhDr. JiˇríMunzar, CSc. Brno, 2006 Zdenekˇ Marecek:ˇ Emil Hadina (1885-1957). Zum literarischen Leben in der Provinz. Brno: Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity, 2006. Schlüßelwörter: Emil Hadina, Karl Hans Strobl, Troppau, Staackmann, Höhenliteratur, Heimatliteratur, Dichterroman, Autorenstrategie. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem pˇredloženoudisertaˇcnípráci zpracoval samostat- nˇea použil pouze uvedenou literaturu. ZdenˇekMareˇcek V Brnˇe29. 3. 2006 ii Danksagung Mein aufrichtiger Dank gehört allen, die mir ermöglicht haben, die Arbeit in diesen (mich immer noch nicht ganz befriedigenden) Zu- stand zu bringen: – an erster Stelle dem Betreuer meiner Arbeit Prof. PhDr. JiˇríMun- zar, CSc., der als jahrelanger Institusvorstand und seit meinen Studentenjahren mein Mentor mich ermunterte und beriet; – Prof. PhDr. Ludvík Václavek, CSc., dem Vater der Idee, Hadi- nas Werk zu untersuchen, einem geduldigen Förderer meiner Bemühungen und dem Oponenten; – meinem zweiten Opponenten Prof. Dr. phil. Klaus Heydemann, meinem großen Vorbild als Ginzkey-Spezialist, dem ich einen Einblick in die Methodologie der Sozialgeschichte der Literatur und manche sprachliche Korrektur verdanke; – Dr. phil. Alois Kernbauer vom Universitätsarchiv Graz, der mir Hadinas Dissertation zukommen ließ; – Dr. phil. Becher für die Materialien zu Hadinas Versuch, Mit- glied der Reichsschrifttumskammer -

Schreker's Die Gezeichneten

"A Superabundance of Music": Reflections on Vienna, Italy and German Opera, 1912-1918 Robert Blackburn I Romain Rolland's remark that in Germany there was too much music 1 has a particular resonance for the period just before and just after the First World War. It was an age of several different and parallel cultural impulses, with the new forces of Expressionism running alongside continuing fascination with the icons and imagery ofJugendstil and neo-rornanticism, the haunting conservative inwardness of Pfitzner's Palestrina cheek by jowl with rococo stylisation (Der Rosenkavalier and Ariadne auf Naxos) and the search for a re- animation of the commedia dell'arte (Ariadne again and Busoni's parodistic and often sinister Arlecchino, as well es Pierrot Lunaire and Debussy's Cello Sonata). The lure of new opera was paramount and there seemed to be no limit to the demand and market in Germany. Strauss's success with Salome after 1905 not only enable him to build a villa at Garmisch, but created a particular sound-world and atmosphere of sultriness, obsession and irrationalism which had a profound influence on the time. It was, as Strauss observed, "a symphony in the medium of drama, and is psychological like all music". 2 So, too, was Elektra, though this was received more coolly at the time by many. The perceptive Paul Bekker (aged 27 in 1909) was among the few to recognise it at once for the masterpiece it is.3 In 1911 it was far from clear that Del' Rosenkavalier would become Strauss' and Hofinannsthal's biggest commercial success, nor in 1916 that Ariadne all! Naxos would eventually be described as their most original collaboration.' 6 Revista Musica, Sao Paulo, v.5, n. -

Bibliographic Essay for Alex Ross's Wagnerism: Art and Politics in The

Bibliographic Essay for Alex Ross’s Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music The notes in the printed text of Wagnerism give sources for material quoted in the book and cite the important primary and secondary literature on which I drew. From those notes, I have assembled an alphabetized bibliography of works cited. However, my reading and research went well beyond the literature catalogued in the notes, and in the following essay I hope to give as complete an accounting of my research as I can manage. Perhaps the document will be of use to scholars doing further work on the phenomenon of Wagnerism. As I indicate in my introduction and acknowledgments, I am tremendously grateful to those who have gone before me; a not inconsiderable number of them volunteered personal assistance as I worked. Wagner has been the subject of thousands of books—although the often-quoted claim that more has been written about him than anyone except Christ or Napoleon is one of many indestructible Wagner myths. (Barry Millington, long established one of the leading Wagner commentators in English, disposes of it briskly in an essay on “Myths and Legends” in his Wagner Compendium, published by Schirmer in 1992.) Nonetheless, the literature is vast, and since Wagner himself is not the central focus of my book I won’t attempt any sort of broad survey here. I will, however, indicate the major works that guided me in assembling the piecemeal portrait of Wagner that emerges in my book. The most extensive biography, though by no means the most trustworthy, is the six- volume, thirty-one-hundred-page life by the Wagner idolater Carl Friedrich Glasenapp (Breitkopf und Härtel, 1894–1911). -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

Salzburger Verlagsgeschichte Von 1945 Bis 1959

Salzburger Verlagsgeschichte von 1945 bis 1959 Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des Magistergrades an der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Salzburg betreut von O.Univ.Prof. Dr. Michael Schmolke Institut für Kommunikationswissenschaft eingereicht von Ursula Kramml Salzburg 2002 1 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Einleitung 8 Literatur zu den Verlagen 9 Die Suche nach den Verlagen 12 Vom Verlagsnamen zum Verlagsportrait 13 Das Erstellen von Verlagsprogrammen 15 Darstellung des Kontextes und Literatur dazu 18 1. Die Bedingungen während der Jahre 1945 bis 1959/60 21 1.1 Die Ausgangssituation: Verlage während der Jahre 1918 bis 1944/45 21 1.2 Verlagsleben zwischen 1945 und 1948 22 1.2.1 Die Zeit vor der ersten Verlagsgenehmigung 22 1.2.2 Die Tätigkeit des Verlegers auf Grund der Bestimmungen der armerikanischen Besatzungsmacht und der österreichischen Regierung 28 1.2.3 Das Verlegen einzelner Werke auf Grund der Bestimmungen von der amerikanischen Besatzungsmacht und der österreichischen Regierung 31 1.2.4 Boom und Krise 33 1.2.5 Mangel an vielem, Papierbewirtschaftung, Lizenzvermittlung 35 EXKURS: Verlage der ersten Stunde und ihre Titel 41 Liste der in Salzburg zwischen 1945 und 1947 verlegten Titel 42 1.3 Verlagsleben 1948 bis 1955 55 1.3.1 Rekonzessionierung, Buchaußenhandel, -preis und -förderung 55 1.3.2 Die zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus verlegten Autoren wurden wieder verlegt 58 1.4 Verlagsleben 1955 bis zu Beginn der 60er Jahre: Taschenbuch und Buchgemeinschaften 63 2 2. Salzburger Verlage von 1945 bis 1959 im Überblick 65 2.1. Wiederaufnahme der Verlegerischen Tätigkeit 65 2.1.1 Die bekannten Verlage 65 Otto Müller 65 Verlag Anton Pustet 98 Salzburger Druckerei und Verlag 116 R.