The Audio Mixer As Creative Tool in Musical Composition and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

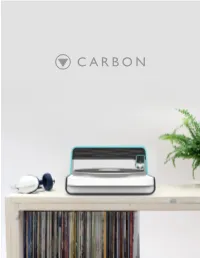

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value in Recorded Music

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value In Recorded Music MFA Advanced Product Design Degree Project Report June 2015 Christopher Wright Canada www.cllw.co TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 - Introduction Introduction 06 The Problem With Streaming 08 The Vinyl Revival 10 The Project 12 Part 2 - Research Record Sales Statistics 16 Music Consumption Trends 18 Vinyl Pros and Cons 20 How Records Are Made 22 Vinyl Pressing Prices 24 Mastering Lathes 26 Historical Review 28 Competitive Analysis 30 Abstract Digital Record Experiments 32 Analogous Research 34 Vinyl records have re-emerged as the preferred format for music fans and artists Part 3 - Field Research alike. The problem is that producing vinyl Research Trip - Toronto 38 records is slow and expensive; this makes it Expert Interviews 40 difcult for up-and-coming artists to release User Interviews 44 their music on vinyl. What if you could Extreme User Interview 48 make your own records at home? Part 4 - Analysis Research Analysis 52 User Insights 54 User Needs Analysis 56 Personas 58 Use Environment 62 Special Thanks To: Technology Analysis 64 Product Analysis 66 Anders Smith Thomas Degn Part 5 - Strategy Warren Schierling Design Opportunity 70 George Graves & Lacquer Channel Goals & Wishes 72 Tyler Macdonald Target Market 74 My APD 2 classmates and the UID crew Inspiration & Design Principles 76 Part 6 - Design Process Initial Sketch Exploration 80 Sacrificial Concepts 82 Concept Development 84 Final Direction 94 Part 7 - Result Final Design 98 Features and Details 100 Carbon Cut App 104 Cutter-Head Details 106 Mechanical Design 108 Conclusions & Reflections 112 References 114 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 4 5 INTRODUCTION Personal Interest I have always been a music lover; I began playing in bands when I was 14, and decided in my later teenage years that I would pursue a career in music. -

Scary Monsters and Pervasive Slights: Genre Construction, Mainstreaming, and Processes of Authentication and Gendered Discourse in Dubstep

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-18-2013 12:00 AM Scary Monsters and Pervasive Slights: Genre Construction, Mainstreaming, and Processes of Authentication and Gendered Discourse in Dubstep Kyle Fowle The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kyle Fowle 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Fowle, Kyle, "Scary Monsters and Pervasive Slights: Genre Construction, Mainstreaming, and Processes of Authentication and Gendered Discourse in Dubstep" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1203. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1203 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCARY MONSTERS AND PERVASIVE SLIGHTS: GENRE CONSTRUCTION, MAINSTREAMING, AND PROCESSES OF AUTHENTICATION AND GENDERED DISCOURSE IN DUBSTEP (Monograph) by Kyle Fowle Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Popular Music and Culture The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Kyle Fowle 2013 ii Abstract This thesis examines discourses on dubstep, a currently popular form of electronic dance music (EDM). The thesis identifies discursive patterns in the received historical narrative of EDM and explores how those patterns may or may not manifest themselves in the current discourses on dubstep. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Soundscape of the Factory Floor a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Soundscape of the Factory Floor A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Visual Art by Seth Alexander Ferris Committe in Charge: Professor Benjamin Bratton, Chair Professor Sheldon Brown Professor Ricardo Dominguez Professor Miller Puckette Professor Mariana Botey Wardwell 2017 Copyright Seth Alexander Ferris, 2017 All rights reserved The Thesis of Seth Alexander Ferris is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .................................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................... iv Abstract of the Thesis ......................................................................................................................... v Chapter One ......................................................................................................................................... -

Sound Design and Recorded Music Part One

PART ONE: SOUND DESIGN AND RECORDED MUSIC Far too often in today’s production work the individual assigned to be the designer of sound and other accompanying music simply goes to a collection of prerecorded music (or “101 Sound Effects”) and transfers the required piece to whatever medium of playback is being used for production. Anyone trained on the equipment can do this and the expenditure of creative thought and planning is practically nil. If a sound designer is participating on a production team, the evolution of the production will be influenced by each designer’s input and indeed, the final effect may not be found on a prerecorded compact disc (CD). And why should it be? The costume designer cannot shop for flapper dresses of the 1920s nor can the scenic elements be procured at any hardware store. Part of the pleasure, indeed responsibility, of each designer is to create the solution that captures the look and feel required by the specific production. And part of that feel is certainly enhanced by the choices of the sound designer. Because theatrical production is a total design effort, it is incumbent on each designer to understand the script, and be in accord with the other designers, the director, the producer, and the writers. This should include not only theatre but film, television and any other installation which is designed to affect an audience in a particular planned and organized manner. This is not always the case. The best assurance of good teamwork is understanding and acceptance between designers about the paths the production will take. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

GUNS DON’T GLOBALIZE… LAZERS DO: GLOBALIZATION, TECHNOLOGY, AND TRINIDADIAN SOCA By LUCAS ANDREW REICHLE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Lucas Andrew Reichle To Anne Thingsaker, for her endless love, patience, and understanding, thank you ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my family. You are my motivation and a constant source of love and appreciation. I would also like to thank my parents and siblings for always being there with moral support and believing in me. I would like to extend special gratitude to my sister Tisha Marie for spending so much time editing this thesis. I would like to thank Dr. Eugene Novotney for introducing me to pan, calypso, and soca, you have given me direction and exposed a passion in me for culture and non-western music I did not know existed until I met you. Thank you for sharing your network of contacts that allowed me to conduct research in Trinidad with ease. I would also like to thank the rest of my educators at Humboldt State University for providing me with the fantastic education that got me to where I am today. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Welson Tremura, and all the rest of my professors at the University of Florida, for providing me with the tools and opportunity to achieve this feat. I would also like to express my gratitude for my colleagues and peers at UF for your friendship and for helping me along the way in this process. -

Recorded Music in American Life: the Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890–1945

Recorded Music in American Life: The Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890–1945 William Howland Kenney OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS recorded music in american life This page intentionally left blank RECORDED MUSIC IN AMERICAN LIFE The Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890–1945 William Howland Kenney 1 New York Oxford Oxford University Press Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1999 by William Howland Kenney Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kenney, William Howland. Recorded music in American life : the phonograph and popular memory, 1890–1945 / William Howland Kenney. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-510046-8; 0-19-517177-2 (pbk.) 1. Popular music—Social aspects—United States. 2. Phonograph— Social aspects—United States. 3. Sound recording industry—United States—History. 4. Popular culture—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. ML3477.K46 1999 306.4'84—dc21 98-8611 98765 43 21 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper iv introductionDisclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. -

Vinyl: a History of the Analogue Record

Vinyl: A History of the Analogue Record Richard Osborne VINYL: A HISTORY OF THE ANALOGUE RECORD For Maria Vinyl: A History of the Analogue Record RICHARD OSBORNE Middlesex University, UK © Richard Osborne 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Richard Osborne has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3–1 Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-3818 England USA www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Osborne, Richard. Vinyl : a history of the analogue record. — (Ashgate popular and folk music series) 1. Sound—Recording and reproducing—Equipment and supplies—History. 2. Sound—Recording and reproducing—Equipment and supplies—Materials. 3. Sound recordings—History. I. Title II. Series 781.4’9’09–dc23 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Osborne, Richard, 1967– Vinyl : a history of the analogue record / by Richard Osborne. p. cm. — (Ashgate popular and folk music series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-4027-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4094-4028-4 (ebook) 1. Sound recordings—History. 2. Sound recording industry—History. I. Title. ML3790.O825 2013 384—dc23 2012021796 ISBN 9781409440277 (hbk) ISBN 9781409440284 (ebk – PDF) ISBN 9781409472049 (ebk – ePUB) V Printed and bound in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group, UK.