Vinyl: a History of the Analogue Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

I Still Believe

I still believe I still believe was first recorded by Bunny DeBarge in 1986. A year later, Chrysalis artist Brenda K. Starr also recorded a version of the song, who just happened to be employing a back-up singer 0351 5” CD-Single from Austria named Mariah Carey at the time. In 1998, Mariah recorded her own SAMPCS 6452 promo in slimline jewelcase version for her compilation album #1’s. I still believe was released as a single on February 9, 1999 in the USA and on March 1, 1999 Tracklisting: in Europe. On February 23, a remix single, called I still believe/Pure 1. I still believe (Album Version) imagination, was released. On the back cover is a little message for the dj’s: “I want to thank everyone at radio for your continued support. I appreciate ya! Love, Mariah.” On January 5, 2001, Kathi Pinto, a songwriter from California, filed a copyright infringement lawsuit in United States District Court for the Central District of California over the single. Kathi alleges in the suit that she co-wrote a song entitled I still believe in 1981, which was sold to music publisher Galen Senogles at Simple Song Music that same year. As the song switched hands among various publish- 0986 5” CD-Single from Austria SAMPCS 666781-8 ers and record execs over the years through Pinto’s desire for a re- promo without sleeve cording contract, it eventually ended up in the hands of Tom Sturges at Chrysalis Records around 1985. Sturges allegedly helped pen a Tracklisting: tune called I still believe with Antonina Armato and Beppe Canarelli. -

The Music Industry and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture

The Music Industry: Demarcating Rhyme from Reason and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture I. Introduction The recording industry has a long history rooted deep in technological achievement and social undercurrents. In place to support such an infrastructure, is a lengthy list of technological advancements, political connections, lobbying efforts, marketing campaigns, and lawsuits. Ever since the early 20th century, record labels have embarked on a perpetual campaign to strengthen their control over recording artists and those technologies and distribution channels that fuel the success of such artists. As evident through the current draconian recording contracts currently foisted on artists, this campaign has often resulted in success. However, the rise of MTV, peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and even radio itself also proves that the labels have suffered numerous defeats. Unfortunately, most music listeners in the world have remained oblivious to the business practices employed by the recording industry. As long as the appearance of artistic freedom exists, as reinforced through the media, most consumers have typically been content to let sleeping dogs lie. Such a relaxed viewpoint, however, has resulted in numerous policies that have boosted industry profits at the expense of consumer dollars. Only when blatant coercion has occurred, as evidenced through the payola scandals of the 1950s, does the general public react in opposition to such practices. Ironically though, such outbursts of conscience have only served to drive payola practices further underground—hidden behind co-operative advertising agreements and outside promotion consultants. The advent of the Internet in the last decade, however, has thrown the dynamics of the recording industry into a state of disarray. -

Spring Records Discography 4700 Series

Spring Records Discography 4700 series SPR 4701 - The Sounds Of Simon - JOE SIMON [1971] To Lay Down Beside You/I Can’t See Nobody/Most Of All/No More Me/Your Time To Cry//Help Me Make It Through The Night/My Woman, My Woman, My Wife/I Love You More (Than Anything)/Georgia Blue/All My Hard Times 5700 series SPR 5702 - Drowning In The Sea Of Love - JOE SIMON [1972] Drowning In The Sea Of Love/Glad To Be Your Lover/Something You Can Do Today/I Found My Dad/The Mirror Don’t Lie//Ole Night Owl/You Are Everything/If/Let Me Be The One (The One Who Loves You)/Pool Of Bad Luck SPR 5703 - Millie Jackson - MILLIE JACKSON [1972] If This Is Love/I Ain’t Giving Up/I Miss You Baby/A Child Of God (It’s Hard To Believe)/Ask Me What You Want//My Man, A Sweet Man/You’re The Joy Of My Life/I Gotta Get Away (From My Own Self)/I Just Can’t Stand It/Strange Things SPR 5704 - The Power Of Joe Simon - JOE SIMON [1973] Drowning In The Sea Of Love/Georgia Blue/Help Me Make It Through The Night/Power Of Love/Step By Step/Talk Don’t Bother Me/To Lay Down Beside You/Trouble In My Home/You Are The One/Your Time To Cry [*] SPR 5705 - Simon Country - JOE SIMON [1973] Do You Know What It’s Like To Be Lonesome?/Five Hundred Miles/Woman Without Love/You Don’t Know Me/To Get To You//Before The Next Teardrop Falls/Someone To Give My Love To/Good Things/Kiss An Angel Good Mornin’ SPR 5706 - It Hurts So Good - MILLIE JACKSON [1973] Breakaway/Close My Eyes/Don’t Send Nobody Else/Good To The Very Last Drop/Help Yourself/Hurts So Good/Hypocrisy/I Cry/Love Doctor/Now That You Got -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

New Books on Art & Culture

S11_cover_OUT.qxp:cat_s05_cover1 12/2/10 3:13 PM Page 1 Presorted | Bound Printed DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS,INC Matter U.S. Postage PAID Madison, WI Permit No. 2223 DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS . SPRING 2011 NEW BOOKS ON SPRING 2011 BOOKS ON ART AND CULTURE ART & CULTURE ISBN 978-1-935202-48-6 $3.50 DISTRIBUTED ART PUBLISHERS, INC. 155 SIXTH AVENUE 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 WWW.ARTBOOK.COM GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS ArtHistory 64 Art 76 BookDesign 88 Photography 90 Writings&GroupExhibitions 102 Architecture&Design 110 Journals 118 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Special&LimitedEditions 124 Art 125 GroupExhibitions 147 Photography 157 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Architecture&Design 169 Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production Nicole Lee BacklistHighlights 175 Data Production Index 179 Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Sara Marcus Cameron Shaw Eleanor Strehl Printing Royle Printing Front cover image: Mark Morrisroe,“Fascination (Jonathan),” c. 1983. C-print, negative sandwich, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. F.C. Gundlach Foundation. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur. From Mark Morrisroe, published by JRP|Ringier. See Page 6. Back cover image: Rodney Graham,“Weathervane (West),” 2007. From Rodney Graham: British Weathervanes, published by Christine Burgin/Donald Young. See page 87. Takashi Murakami,“Flower Matango” (2001–2006), in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. See Murakami Versailles, published by Editions Xavier Barral, p. 16. GENERAL INTEREST 4 | D.A.P. | T:800.338.2665 F:800.478.3128 GENERAL INTEREST Drawn from the collection of the Library of Congress, this beautifully produced book is a celebration of the history of the photographic album, from the turn of last century to the present day. -

The Audio Mixer As Creative Tool in Musical Composition and Performance

Die Reihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” stellt Arbeiten des Instituts fur¨ Elektronische Musik und Akustik Graz zu den Themenbereichen Akustik, Com- putermusik, Musikelektronik und Medienphilosophie vor. Dabei handelt es sich meist um Ergebnisse von Forschungsarbeiten am Institut oder um uberarbeitete¨ Vortrage¨ von InstitutsmitarbeiterInnen. Daruber¨ hinaus soll hier eine Diskussionsplattform zu den genannten Themen entstehen. Beitrage¨ konnen¨ auch eine Beschreibung von Projekten und Ideen sein, die sich in Entwicklung befinden und noch nicht fertiggestellt sind. Wir hoffen, dass die Schriftreihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” eine An- regung fur¨ Ihre wissenschaftliche und kunstlerische¨ Arbeit bietet. Alois Sontacchi (Herausgeber) The series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” (contributions to electronic music) presents papers by the Institute of Electronic Music Graz on various topics inclu- ding acoustics, computer music, music electronics and media philosophy. The contributions present results of research performed at the institute or edited lec- tures held by members of the institute. The series shall establish a discussion forum for the above mentioned fields. Ar- ticles should be written in English or German. The contributions can also deal with the description of projects and ideas that are still in preparation and not yet completed. We hope that the series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” will provide thought- provoking ideas for your scientific and artistic work. Alois Sontacchi (editor) The audio mixer as -

Dance Chart, 1989-10

DANCE Mt SIC INTERNATIONAL CLUB PLAY AUSTRALIA OCT. 1989 NATIONAL TOP 40 DANCE TRAX • TM LM KEY TITLE/AR IST CO PAN 1 13 0 Dressed For Success - ROXETTE EMI 2 1 • Batdance -PRINCE WEA 3 - • Cherish - MADONNA WEA 4 4 * Funky Cold Medina - TONE LOC FEST. 5 14 • Baby Don't Forget My Number - MILLI VANILLI BMG 6 2 + Right Back Where We Started - SINITTA CBS 7 23 • Bat Attack - CRIME FIGHTERS INC. BMG 8 5 0 Baby I Don't Care - TRANSVISION VAMP WEA 9 9 + This Time I Know It's For Real - DONNA SUMMER WEA 10 3 ■ The Right Stuff - NEW KIDS ON THE BLOCK CBS 11 8 • Express Yourself - MADONNA WEA 12 6 * Bamboleo - GYPSY KINGS CBS 13 7 • The Look - ROXETTE EMI 14 12 • Forever Your Girl - PAULA ABDUL VIRGIN 15 10 711 Max Mix 8 - VARIOUS ARTISTS COL* 16 - 4. You'll Never Stop Me Lovin' You - SONIA EMI 17 19 III Girl You Know It's True - MILLIE VANILLI BMG 18 - • Miss You Much - JANET JACKSON FEST. 19 11 0 Say Goodbye - INDECENT OBSESSION CBS 20 35 • Keep On Moving - SOUL 11 SOUL VIRGIN 21 15 0 Ain't Nobody Better - INNER CITY VIRGIN 22 16 0 Good Life - INNER CITY VIRGIN 23 31 >41 Acid Mix - VARIOUS ARTISTS COL* 24 27 • Straight Up - PAULA ABDUL EMI 25 21 • Send Me An Angel '89 - REAL LIFE BMG 26 20 • Pop Musik '89 - M BMG 27 RE * We Want Some Pussy - 2 LIVE CREW COL* 28 RE • Come Home With Me Baby - DEAD OR ALIVE CBS 29 17 • My Perrogative - BOBBY BROWN WEA 30 - • Deep in Vogue - MALCOLM McCLAREN CBS 31 - • Grandpa's Party - MONIE LOVE EMI 32 24 • Strokin - CLARENCE CARTER COL 33 40 • What You Don't Know - EXPOSE BMG 34 18 + Oh What A Night - FOUR SEASONS COL * 35 36 4. -

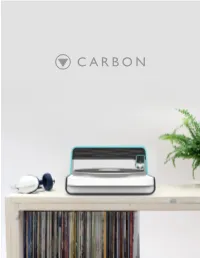

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value in Recorded Music

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value In Recorded Music MFA Advanced Product Design Degree Project Report June 2015 Christopher Wright Canada www.cllw.co TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 - Introduction Introduction 06 The Problem With Streaming 08 The Vinyl Revival 10 The Project 12 Part 2 - Research Record Sales Statistics 16 Music Consumption Trends 18 Vinyl Pros and Cons 20 How Records Are Made 22 Vinyl Pressing Prices 24 Mastering Lathes 26 Historical Review 28 Competitive Analysis 30 Abstract Digital Record Experiments 32 Analogous Research 34 Vinyl records have re-emerged as the preferred format for music fans and artists Part 3 - Field Research alike. The problem is that producing vinyl Research Trip - Toronto 38 records is slow and expensive; this makes it Expert Interviews 40 difcult for up-and-coming artists to release User Interviews 44 their music on vinyl. What if you could Extreme User Interview 48 make your own records at home? Part 4 - Analysis Research Analysis 52 User Insights 54 User Needs Analysis 56 Personas 58 Use Environment 62 Special Thanks To: Technology Analysis 64 Product Analysis 66 Anders Smith Thomas Degn Part 5 - Strategy Warren Schierling Design Opportunity 70 George Graves & Lacquer Channel Goals & Wishes 72 Tyler Macdonald Target Market 74 My APD 2 classmates and the UID crew Inspiration & Design Principles 76 Part 6 - Design Process Initial Sketch Exploration 80 Sacrificial Concepts 82 Concept Development 84 Final Direction 94 Part 7 - Result Final Design 98 Features and Details 100 Carbon Cut App 104 Cutter-Head Details 106 Mechanical Design 108 Conclusions & Reflections 112 References 114 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 4 5 INTRODUCTION Personal Interest I have always been a music lover; I began playing in bands when I was 14, and decided in my later teenage years that I would pursue a career in music.