UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Soundscape of the Factory Floor a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Does Art Sound Like? an Exploration of Art Through Sound

What does Art Sound Like? An exploration of Art through Sound. Developed by: Catherine Ewer Suggested Grade Level(s): 1 –3 Suggested Length of Class Time: One 60-minute class Subject Areas: Visual Art, Language Art Rationale When it comes to artwork, there is generally a lot of focus on “looking with our eyes” but much can be gained by entering further into the creative experience through sound. In this lesson students will study a piece of art and interpret it as an audio experience, adding a whole new creative layer. Children love creating Soundscapes and will enjoy the ingenuity and imagination necessary to “hear” a painting. This is truly a creative group experience in which everyone’s input is valuable. During the creation of the Soundscape there will be a lot of discussion around sounds using descriptive vocabulary, which the students can then draw upon as inspiration to create short written narratives. Logistics: Classroom setup – group class work, individual work at desks Materials – image of one or more paintings, large enough to look at as a class, sound recorder, or device capable of recording sound. Suggested resources/images – online image banks from various art gallery and museum sites; art reproduction posters, individual art postcards, etc. Some suggestions for types of images are landscapes, seascapes, crowd scenes or an image rich in action. Suggested Outcomes: Students will be expected to: - Explore a variety of sound sources - Work together in group music and art making - Experiment with language choices in imaginative writing and other ways of representing - Share writing or other representations with others and seek feedback - With assistance, experiment with technology in writing and other forms of representation - Select, organize, and combine (with assistance) relevant information to construct and communicate meaning Introduction: As a class, look closely at an image and examine every part. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

The Psychophysiological Implications of Soundscape: a Systematic Review of Empirical Literature and a Research Agenda

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review The Psychophysiological Implications of Soundscape: A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature and a Research Agenda Mercede Erfanian * , Andrew J. Mitchell , Jian Kang * and Francesco Aletta UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, The Bartlett, University College London (UCL), Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK; [email protected] (A.J.M.); [email protected] (F.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.E.); [email protected] (J.K.); Tel.: +44-(0)20-3108-7338 (J.K.) Received: 16 September 2019; Accepted: 19 September 2019; Published: 21 September 2019 Abstract: The soundscape is defined by the International Standard Organization (ISO) 12913-1 as the human’s perception of the acoustic environment, in context, accompanying physiological and psychological responses. Previous research is synthesized with studies designed to investigate soundscape at the ‘unconscious’ level in an effort to more specifically conceptualize biomarkers of the soundscape. This review aims firstly, to investigate the consistency of methodologies applied for the investigation of physiological aspects of soundscape; secondly, to underline the feasibility of physiological markers as biomarkers of soundscape; and finally, to explore the association between the physiological responses and the well-founded psychological components of the soundscape which are continually advancing. For this review, Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

In Situ Listening: Soundscape, Site and Transphonia

In Situ Listening: Soundscape, Site and Transphonia Marcus Leadley Goldsmiths, University of London PhD Sonic Arts 2015 I hereby declare that the work in this thesis and the works presented in the accompanying portfolio are my own. I am responsible for the majority of photographic images used herein and I therefore own and control copyrights. Where necessary, permissions have been acquired, and credits assigned. Signed, Marcus Leadley © 2015 2 Abstract This enquiry represents an exploration of environmental sound and artistic practice from the perspectives of in situ listening and transphonia. The initial term, in situ listening, has been coined by the author in order to constellate a group of intellectual trajectories and artists’ practices that engage with recorded sound and share a common theme: that the listening context, the relationship between mediated sound and site, is an integral part of the engagement process. Heikki Uimonen (2005, p.63) defines transphonia as the, “mechanical, electroacoustical or digital recording, reproduction and relocating of sounds.” The term applies to sound that is relocated from one location to another, or sound that is recorded at a site and then mixed with the sound of the prevailing environment. The experience of the latter, which is a key concern for this thesis, may be encountered during the field recording process when one ‘listens back’ to recordings while on site or during the presentation of site-specific sound art work. Twelve sound installations, each based on field recordings, were produced in order to progress the investigation. Installations were created using a personally devised approach that was rigorous, informed, and iterative. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Dubplate Literature: Distribution Beyond the Market

Dubplate literature: distribution beyond the market Joshua Mostafa, 2014 Te trajectories of the commercial imperative and of cultural production are often opposed, and at best orthogonal. Te rise of digital media and discounted online sales threatens to upset their fragile compromise. New approaches must be found to sustain literary publishing. I explore options beyond the market: the subscription model, private circulation, and fnally suggest ‘public circulation’ backed by a relationship of patronage and mutual beneft between literary publishers and public libraries. We hardly need reminding that literary book publishing is beset on all sides by hostile forces: the long-term erosion of reading for entertainment by other, shiner, media; aggressive retailer strategies predicated on deep discounts; and the rush to digitisation, with its concomitant depredations—the devaluation of literature when digitally encoded, the never-ending demand for lower prices, the threat of ‘piracy’ or fle sharing, and the shifting of the reader’s economic role from customer to advertising target. Most of these effects are well-rehearsed, but I suspect the last is understood insufficiently widely. Te ebook reader is not simply what it claims, an innocent and convenient device for reading texts. It is more like the two-way television in 1984, which watches you as you watch it.1 Even buying a physical book online is to submit to a degree of behavioural profling: your purchase is added to a bundle of data that allows its advertising algorithm to target you with other products you might like to buy. But that’s merely the tip of the iceberg. -

The Aura of Dubplate Specials in Finnish Reggae Sound System Culture

“Chase Sound Boys Out of Earth”: The Aura of Dubplate Specials in Finnish Reggae Sound System Culture Feature Article Kim Ramstedt Åbo Akademi University (Finland) Abstract This study seeks to expand our understanding of how dubplate specials are produced, circulated, and culturally valued in the international reggae sound system culture of the dub diaspora by analysing the production and performance of “Chase the Devil” (2005), a dubplate special commissioned by the Finnish MPV sound system from Jamaican reggae singer Max Romeo. A dubplate special is a unique recording where, typically, a reggae artist re-records the vocals to one of his or her popular songs with new lyrics that praise the sound system that commissioned the recording. Scholars have previously theorized dubplates using Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura, thereby drawing attention to the exclusivity and uniqueness of these traditionally analog recordings. However, since the advent of digital technologies in both recording and sound system performance, what Benjamin calls the “cult value” of producing and performing dubplates has become increasingly complex and multi-layered, as digital dubplates now remediate prior aesthetic forms of the analog. By turning to ethnographic accounts from the sound system’s DJ selectors, I investigate how digital dubplates are still culturally valued for their aura, even as the very concept of aura falls into question when applied to the recording and performance of digital dubplates. Keywords: aura, dubplate special, DJ, performance, reggae, recording, authenticity Kim Ramstedt is a PhD candidate in musicology at Åbo Akademi University in Finland. In his dissertation project, Ramstedt is studying DJs as cultural intermediaries and the localization of musical cultures through DJ practices. -

The Audio Mixer As Creative Tool in Musical Composition and Performance

Die Reihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” stellt Arbeiten des Instituts fur¨ Elektronische Musik und Akustik Graz zu den Themenbereichen Akustik, Com- putermusik, Musikelektronik und Medienphilosophie vor. Dabei handelt es sich meist um Ergebnisse von Forschungsarbeiten am Institut oder um uberarbeitete¨ Vortrage¨ von InstitutsmitarbeiterInnen. Daruber¨ hinaus soll hier eine Diskussionsplattform zu den genannten Themen entstehen. Beitrage¨ konnen¨ auch eine Beschreibung von Projekten und Ideen sein, die sich in Entwicklung befinden und noch nicht fertiggestellt sind. Wir hoffen, dass die Schriftreihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” eine An- regung fur¨ Ihre wissenschaftliche und kunstlerische¨ Arbeit bietet. Alois Sontacchi (Herausgeber) The series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” (contributions to electronic music) presents papers by the Institute of Electronic Music Graz on various topics inclu- ding acoustics, computer music, music electronics and media philosophy. The contributions present results of research performed at the institute or edited lec- tures held by members of the institute. The series shall establish a discussion forum for the above mentioned fields. Ar- ticles should be written in English or German. The contributions can also deal with the description of projects and ideas that are still in preparation and not yet completed. We hope that the series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” will provide thought- provoking ideas for your scientific and artistic work. Alois Sontacchi (editor) The audio mixer as -

FURTHERING the DRUM'n'bass RACE: a Treatise on Loop

FURTHERING THE DRUM'N'BASS RACE: A Treatise on Loop Development By Cape Canaveral e-mail: [email protected] Version 1.2 September 1999 Updated versions will be found at www.spinwarp.com or www.lanset.com/shansen. All statements are IMHO. Forward: So, you'd like to make some beats? Want them to sound like 'real' beats, not the lame beats you've been making? Maybe you've read some tips in 'Keyboard' or 'Future Music' and are wondering why they haven't helped. At all. Well, we've all been there. But now, I'm going to tell you how beats are really made. This is the stuff those posers at the magazines don't even know, and the pros don't want you to. But I say forget secrets: let the music stand on its own merit, not on some simple tricks! In this article I will cover two ways of making drum loops, with extra information for jungle programming. But that is information all drum programmers need as well, as it is vital to how your new beats will sound and feel. Before You Begin: If you are no good at music-making at all, or are completely new to this, this article won't make you the Chemical Brothers (well, a Chemical Brother... er, whatever). But if you're OK at making beats, here are some basic and not-so-basic tips for you try, or at least be familiar with: 1. When you sample off a record, or even any other source, you may want to add to the sound without changing it a lot. -

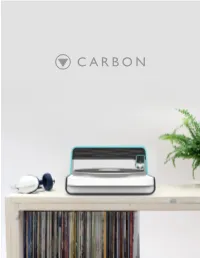

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value in Recorded Music

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value In Recorded Music MFA Advanced Product Design Degree Project Report June 2015 Christopher Wright Canada www.cllw.co TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 - Introduction Introduction 06 The Problem With Streaming 08 The Vinyl Revival 10 The Project 12 Part 2 - Research Record Sales Statistics 16 Music Consumption Trends 18 Vinyl Pros and Cons 20 How Records Are Made 22 Vinyl Pressing Prices 24 Mastering Lathes 26 Historical Review 28 Competitive Analysis 30 Abstract Digital Record Experiments 32 Analogous Research 34 Vinyl records have re-emerged as the preferred format for music fans and artists Part 3 - Field Research alike. The problem is that producing vinyl Research Trip - Toronto 38 records is slow and expensive; this makes it Expert Interviews 40 difcult for up-and-coming artists to release User Interviews 44 their music on vinyl. What if you could Extreme User Interview 48 make your own records at home? Part 4 - Analysis Research Analysis 52 User Insights 54 User Needs Analysis 56 Personas 58 Use Environment 62 Special Thanks To: Technology Analysis 64 Product Analysis 66 Anders Smith Thomas Degn Part 5 - Strategy Warren Schierling Design Opportunity 70 George Graves & Lacquer Channel Goals & Wishes 72 Tyler Macdonald Target Market 74 My APD 2 classmates and the UID crew Inspiration & Design Principles 76 Part 6 - Design Process Initial Sketch Exploration 80 Sacrificial Concepts 82 Concept Development 84 Final Direction 94 Part 7 - Result Final Design 98 Features and Details 100 Carbon Cut App 104 Cutter-Head Details 106 Mechanical Design 108 Conclusions & Reflections 112 References 114 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 4 5 INTRODUCTION Personal Interest I have always been a music lover; I began playing in bands when I was 14, and decided in my later teenage years that I would pursue a career in music.