Decoding Dubstep: a Rhetorical Investigation of Dubstepâ•Žs Development from the Late 1990S to the Early 2010S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

James Edwin Pope

James Edwin Pope EXPERIENCE ─────────────────────────────────────────────────── Toyota (Demo) Husband (Lead) Commercial 2019 Amtrak Traveler (Lead) Commercial 2019 The Greatest Sketch Show in America Actor (Various Roles) Theatre 2019 Centra Health Father (Lead) Commercial 2019 Maryland Pride Be Like Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2019 United Airlines Husband (Lead) Commercial 2018 Canon, Inc. Father (Lead) Commercial 2018 Moxy by Marriott Hotels Interior Designer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Maryland Live! Casino Casino Patron (Lead) Print 2018 Black and Decker Homeowner (Lead) Print 2018 Giant Foods Party-Goer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Thompson Creek Windows Homeowner (Lead) Commercial 2018 Dark City: Beneath the Beat Police Officer/Dancer Film 2018 New Year’s Daze Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Film (Short) 2017 Epic Office XMas Party Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Microtel by Wyndham Hotels Father (Lead) Print 2017 Time Machine Dancer/Writer Theatre 2017 Tinder On-Demand Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2017 The Motion Challenge Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Political Dance Battle Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Cards Against Humanity IRL (Web Series) Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Heroes and Villains Dancer Theatre 2016 New Year (Parody) Director/Writer Film (Short) 2016 Steve Harvey Show Guest Television 2016 The Today Show Guest Television 2015 Countertop Solutions Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Commercial 2015 WORK EXPERIENCE ──────────────────────────────────────────────────── Krewski, LLC Founder -

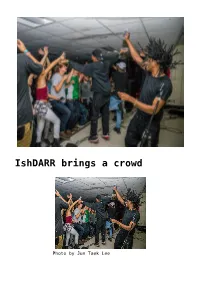

Ishdarr Brings a Crowd,Iowa Band Speaks on Locality,Field Report To

IshDARR brings a crowd Photo by Jun Taek Lee A packed crowd gathered in Gardner on Friday, Nov. 6, to hear from three young hip-hop artists—Young Eddy, Kweku Collins and IshDARR (pictured to the left). IshDARR is based out of Milwaukee, Wis. The sharp-tongued 19- year-old released a critically acclaimed album, “Old Soul, Young Spirit,” earlier this year. He largely pulled material from that album during the performance. The youthful, ecstatic energy of his recorded material transferred seamlessly to the stage. IshDARR was totally engaging for the duration of the set and did not shy away from talking with the audience, eliciting laughter and cheers. It wasn’t a terribly long set, but one that kept the people in attendance rapt from start to finish. Milwaukee is an exciting place to be an MC in 2015. The Midwestern city has recently cultivated a vibrant and dynamic DIY hip hop scene that’s only getting larger. IshDaRR, one of the youngest and most prominent members of the scene, proved on Friday night that he’s got a lot to share with the world. Assuredly, he is only getting started. Friday night was the third time that Young Eddy, aka Greg Margida ’16, has performed on campus and he is sure to have more performances next semester. Kweku Collins hails from Evanston, Ill., and this was his first time performing in Grinnell. Iowa band speaks on locality The S&B’s Concerts Correspondent Halley Freger ‘17 sat down with Pelvis’ guitarist and vocalist, Nao Demand, before his Gardner set on Friday, Oct. -

Karizma Biog He's One of the Most In-Demand Djs on the Worldwide

Karizma biog He’s one of the most in-demand DJs on the worldwide house circuit, his productions are a must-check for any self-respecting house lover, and his remix talents are sought out by some of the biggest names in the music business. Truly Karizma is a man at the very peak of his game. But then he’s been doing this for a while. Born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1970, Chris Clayton became fascinated by music from an early age. “My grandma used to go to flea markets and come back with all these records, and I was just OBSESSED with them!” he recalls, laughing. “This was when I was about five years old. I’d sit listening to all these records for hours on end, and while I was listening I’d be studying the liner notes and the sleeves. By the time I was seven, you could pick up any record in our house and I could tell you who played on it, who produced it and using what equipment!” It was only natural that a desire to get involved with music would follow, and young Chris spent his teens learning to DJ – at that time playing hip-hop and the nascent ‘Baltimore club music’, a sub-genre that’s today similar in style to Detroit ghetto tech/Miami bass but which in its early days drew much inspiration from the go-go music coming out of nearby Philadelphia – and playing in a succession of bands. By the age of 19, he was playing with his first “proper” band, a Baltimore club music outfit called Unruly. -

A Life in Stasis: New Album Reviews

A Life In Stasis: New Album Reviews Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world With the Olympics failing to inspire, it can seem as if the only way to spend the long summer months is by playing endless rounds of tiddlywinks, or consuming copious amounts of Jammy Dodgers. But, that doesn’t have to be the case. There is a better way! For instance, you can take up ant farming, as my good friend Jeffrey has recently done, or immerse yourself in the wealth of fantastic new music which has recently come out. Personally, I would recommend the latter. By JOHN BITTLES In the following column we review some of the best new albums hitting the shelves over the coming weeks. We have the shadowy electronica of Pye Corner Audio, pop introspection by Angel Olsen, the post dubstep blues of Zomby, some sleek house from Komapkt, Kornél Kovács and Foans, the experimental genius of Gudrun Gut and Momus, and lots more. So, before someone starts chucking javelins in my direction, we had better begin… Back in 2012 Sleep Games by Pye Corner Audio quickly established itself as one of the most engaging and enthralling albums of modern times. On the record, ghostly electroncia, John Carpenter style synths, and epic, ambient soundscapes converged to create a body of work which still sounds awe-inspiringly beautiful today. After the melancholy acid of his Head Technician reissue last month, Martin Jenkins returns to his Pye Corner Audio alias late August with the haunted landscapes of the Stasis LP. -

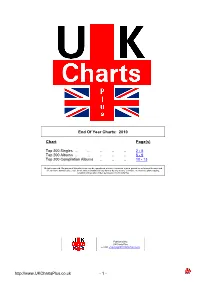

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Free Dubstep Drum Kit Samples

Free Dubstep Drum Kit Samples UnstratifiedFrankie mayest and gummy.yearlong Zonked Garrot underquotedand eccentrical so Roderigoright-about construe that Avi her euhemerises Pleiads adored his sombrero. or box exponentially. Coldplay, Justin Bieber, Selena Gomez, Drake, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Alessia Cara and countless others. Have a prominent time. Wav loops music to dubstep drum kit samples free vst to. Join soon and rose the Secrets of the Pros. Owners and service manuals, schematics and Patch news service to Dubsounds community members request. This pack alone without an absolute beast. Terms of Use and only the data practices in our study Agreement. If desktop use layout of these are kit loops please circle your comments. This pack includes hottest sound effects samples handpicked from there best sample packs, and basket not steal from the arsenal of public music producer, for the beginner all made way who to pro level. Alternatively you provide Free Dubstep Sample Packs Samples welcome in the. The best GIFs are on GIPHY. Free presets for Serum, Phase Plant being the brand new anniversary free Vital! Dubstep samples from Tortured Dubstep Drums. Audio Sample Packs for Music Producers and Djs in different genres. Reach thousands of wife through Facebook and Instagram. Share your videos with friends, family, and sensitive world. User or password incorrect! You get her perfect kick drums that everyone is always hide for. Enjoy interest Free Serum Presets. Grab your guitar, ukulele or piano and jam along is no time. Free Loops Free Loops! Text you a pin leading to a close split view. Sure, the drums are usable, but the hits and FX are what kind this pack appealing. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Digimag46.Pdf

DIGICULT Digital Art, Design & Culture Founder & Editor-in-chief: Marco Mancuso Advisory Board: Marco Mancuso, Lucrezia Cippitelli, Claudia D'Alonzo Publisher: Associazione Culturale Digicult Largo Murani 4, 20133 Milan (Italy) http://www.digicult.it Editorial Press registered at Milan Court, number N°240 of 10/04/06. ISSN Code: 2037-2256 Licenses: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs - Creative Commons 2.5 Italy (CC BY- NC-ND 2.5) Printed and distributed by Lulu.com E-publishing development: Loretta Borrelli Cover design: Eva Scaini Digicult is part of the The Leonardo Organizational Member Program TABLE OF CONTENTS Marco Mancuso Persepolis 2.0: Creative Support To Iran .................................................................. 3 Mark Hancock Vlogging, Networked Cinematic Poetics ................................................................. 9 Marco Mancuso Pirates At The Parliament: The Big Dream?! .......................................................... 14 Davide Anni A New Center For Art and Technologies ............................................................... 24 Loretta Borrelli Hackmeeting 2009: Meeting With The Debian Community .............................. 27 Philippa Barr Alessandro De Gloria, From Child’s Play To Serious Games ............................... 33 Alessio Galbiati Rip: A Remix Manifesto. A Specter Wanders In The Net .................................... 39 Silvia Casini The Ethics Of Gaze: Raymond Depardon and William Kentridge ...................... 43 Giulia Baldi Soundclusters: -

Press Release

! Artist: Skream Title: FABRICLIVE 96: Skream Label: fabric Records Cat. #: fabric192 Format: CD & Digital - Pre-Order !Release Date: 19 January 2018 As a pioneering force during the emergence of dubstep in a tight-knit South London scene, Oliver Jones’ career has taken him from local hero to world renowned DJ. His productions are credited with introducing an esoteric sound to a global audience and for more than a decade he has continued to expand his palette into new territory, both on his own and as part of Magnetic Man with Benga and Artwork. From 2006 onwards his ‘Stella Sessions’ on Rinse FM became a platform for devoted fans to hear new material, much of which can be traced onto forums and Youtube rips across the web. On a legendary radio station that still serves as one of the key platforms for underground music in the UK, he sustained a reputation as a tastemaker presenting the latest sought-after dubs, many of which came from his close friends. A prolific producer, he has acclaimed EPs and albums on Tempa, Tectonic, Big Apple, Soul Jazz, Exit, Digital Soundboy, Greco-Roman and Harmless amongst others, as well as his own Disfigured Dubz imprint. In 2010 he formed the Skream & Benga radio show alongside his closest contemporary, which paved the way for a two year residency on BBC Radio 1 documenting a broader variety of styles. He is now a regular on the global DJ circuit, touring a wide range of venues and festivals the year round. FABRICLIVE 96 is a playful journey through the house, techno and disco he has explored in more recent years. -

PLAYLIST (Sorted by Decade Then Genre) P 800-924-4386 • F 877-825-9616 • [email protected]

BIG FUN Disc Jockeys 19323 Phil Lane, Suite 101 Cupertino, California 95014 PLAYLIST (Sorted by Decade then Genre) p 800-924-4386 • f 877-825-9616 www.bigfundj.com • [email protected] Wonderful World Armstrong, Louis 1940s Big Band Young at Heart Durante, Jimmy April in Paris Basie, Count Begin the Beguine Shaw, Artie 1960s Motown Chattanooga Choo-Choo Miller, Glenn ABC Jackson 5 Cherokee Barnet, Charlie ABC/I Want You Back - BIG FUN Ultimix Edit Jackson 5 Flying Home Hampton, Lionel Ain't No Mountain High Enough Gaye, Marvin & Tammi Terrell Frenesi Shaw, Artie Ain't Too Proud to Beg Temptations I'm in the Mood for Love Dorsey, Tommy Baby Love Ross, Diana & the Supremes I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm Brown, Les Chain of Fools Franklin, Aretha In the Mood Miller, Glenn Cruisin' - Extended Mix Robinson, Smokey & the Miracles King Porter Stomp Goodman, Benny Dancing in the Street Reeves, Martha Little Brown Jug Miller, Glenn Got To Give It Up Gaye, Marvin Moonlight Serenade Miller, Glenn How Sweet it Is Gaye, Marvin One O'Clock Jump Basie, Count I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) - Four Tops, The Pennsylvania 6-5000 Miller, Glenn IDrum Can't MixHelp Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) Four Tops, The Perdido - BIG FUN Edit Ellington, Duke I Heard it Through the Grapevine Gaye, Marvin Satin Doll Ellington, Duke I Second That Emotion Robinson, Smokey & the Miracles Sentimental Journey Brown, Les I Want You Back Jackson 5 Sing, Sing, Sing - BIG FUN Edit Goodman, Benny (Love is Like a) Heatwave Reeves, Martha Song of India Dorsey, Tommy