Sound Design and Recorded Music Part One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Years of the Acoustic Phonograph Its Developmental Origins and Fall from Favor 1877-1929

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE ACOUSTIC PHONOGRAPH ITS DEVELOPMENTAL ORIGINS AND FALL FROM FAVOR 1877-1929 by CARL R. MC QUEARY A SENIOR THESIS IN HISTORICAL AMERICAN TECHNOLOGIES Submitted to the General Studies Committee of the College of Arts and Sciences of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of BACHELOR OF GENERAL STUDIES Approved Accepted Director of General Studies March, 1990 0^ Ac T 3> ^"^^ DEDICATION No. 2) This thesis would not have been possible without the love and support of my wife Laura, who has continued to love me even when I had phonograph parts scattered through out the house. Thanks also to my loving parents, who have always been there for me. The Early Years of the Acoustic Phonograph Its developmental origins and fall from favor 1877-1929 "Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snov^. And everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go." With the recitation of a child's nursery rhyme, thirty-year- old Thomas Alva Edison ushered in a bright new age--the age of recorded sound. Edison's successful reproduction and recording of the human voice was the end result of countless hours of work on his part and represented the culmination of mankind's attempts, over thousands of years, to capture and reproduce the sounds and rhythms of his own vocal utterances as well as those of his environment. Although the industry that Edison spawned continues to this day, the phonograph is much changed, and little resembles the simple acoustical marvel that Edison created. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

The Lab Notebook

Thomas Edison National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior The Lab Notebook Upcoming Exhibits Will Focus on the Origins of Recorded Sound A new exhibit is coming soon to Building 5 that highlights the work of Thomas Edison’s predecessors in the effort to record sound. The exhibit, accompanied by a detailed web presentation, will explore the work of two French scientists who were pioneers in the field of acoustics. In 1857 Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented what he called the phonautograph, a device that traced an image of speech on a glass coated with lampblack, producing a phonautogram. He later changed the recording apparatus to a rotating cylinder and joined with instrument makers to com- mercialize the device. A second Frenchman, Charles Cros, drew inspiration from the telephone and its pair of diaphragms—one that received the speaker’s voice and the second that reconstituted it for the listener. Cros suggested a means of driving a second diaphragm from the tracings of a phonauto- gram, thereby reproducing previously-recorded sound waves. In other words, he conceived of playing back recorded sound. His device was called a paléophone, although he never built one. Despite that, today the French celebrate Cros as the inventor of sound reproduction. Three replicas that will be on display. From left: Scott’s phonautograph, an Edison disc phonograph, and Edison’s 1877 phonograph. Conservation Continues at the Park Workers remove the light The Renova/PARS Environ- fixture outside the front mental Group surveys the door of the Glenmont chemicals in Edison’s desk and home. -

Rome Vaut Bien Un Prix. Une Élite Artistique Au Service De L'état : Les

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 8 Article 8 Issue 2 The Challenge of Caliban 2019 Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger Artl@s, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verger, Annie. "Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968." Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 2 (2019): Article 8. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Artl@s At Work Paris vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger* Résumé Le Dictionnaire biographique des pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome a essentiellement pour objet le recensement du groupe des praticiens envoyés en Italie par l’État, depuis Louis XIV en 1666 jusqu’à la suppression du concours du Prix de Rome en 1968. -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

THE DYNAMIC RANGE POTENTIAL of the PHONOGRAPH by Ronald M

THE DYNAMIC RANGE POTENTIAL OF THE PHONOGRAPH By Ronald M. Bauman his article describes a new transmission standards of even lower added to the quietest passages by the approach for analyzing the quality than our current CD standards. cartridge-preamplifier combination dynamic range of the phono- Unless these standards are dramatical- should be essentially inaudible. graphic playback system, in which the ly upgraded (in terms of information Similarly, the cartridge-preamp sys- cartridge and preamplifier are treated content), we may never have a source tem should be able to clearly repro- as an integrated system. I analyzed of music for our homes that sounds ducd the loudest sounds on record the dynamic range potential of several better than the phonograph. without distortion, compression, or combinations of phono cartridges and Are analog records inherently better clipping. preamplifier amplifying devices and in some sense? Your ears may already The same should be true of CD compared the results to CDs. be telling you that analog can sound playback. The quietest passages Additionally, I speculate about the better than today's digital. I will should be reproduced without added drawbacks of frequency domain char- provide quantitative reasons this may noise or distortion of the rnusic acterizations of musical audio compo- be so. caused by amplitude steps, or sam- nents and suggest that the time pling intervals that are too coarse, or domain may be a more natural frame Qualitative Requirements by filter phase shifts and ringing. The of reference for audio instrumentation The subtlety of detail in the grooves of loudest peaks encoded, as for analog development. -

The Audio Mixer As Creative Tool in Musical Composition and Performance

Die Reihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” stellt Arbeiten des Instituts fur¨ Elektronische Musik und Akustik Graz zu den Themenbereichen Akustik, Com- putermusik, Musikelektronik und Medienphilosophie vor. Dabei handelt es sich meist um Ergebnisse von Forschungsarbeiten am Institut oder um uberarbeitete¨ Vortrage¨ von InstitutsmitarbeiterInnen. Daruber¨ hinaus soll hier eine Diskussionsplattform zu den genannten Themen entstehen. Beitrage¨ konnen¨ auch eine Beschreibung von Projekten und Ideen sein, die sich in Entwicklung befinden und noch nicht fertiggestellt sind. Wir hoffen, dass die Schriftreihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” eine An- regung fur¨ Ihre wissenschaftliche und kunstlerische¨ Arbeit bietet. Alois Sontacchi (Herausgeber) The series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” (contributions to electronic music) presents papers by the Institute of Electronic Music Graz on various topics inclu- ding acoustics, computer music, music electronics and media philosophy. The contributions present results of research performed at the institute or edited lec- tures held by members of the institute. The series shall establish a discussion forum for the above mentioned fields. Ar- ticles should be written in English or German. The contributions can also deal with the description of projects and ideas that are still in preparation and not yet completed. We hope that the series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” will provide thought- provoking ideas for your scientific and artistic work. Alois Sontacchi (editor) The audio mixer as -

Jacques Ibert Represents the Quintessence

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Trois pièces brèves (Three Short Pieces), for Woodwind Quintet Jaques Ibert acques Ibert represents the quintessence awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome on his Jof the Parisian composer in the early- to first try, in 1919. Ibert never departed much mid-20th century: cultivated but not pomp- from an essentially traditional musical lan- ous, technically adept but self-effacing, blend- guage that used explicitly modern harmonies ing the “serious” with the “popular,” typically only as surface details. Apart from the Trois good-spirited and often witty. He was born in pièces brèves, his most frequently visited piec- Paris during the Belle Époque and died in the es today are his orchestral work Escales, his same city 72 years later, having weathered two Flute Concerto, and a neo-Renaissance ballet world wars. His mother, who was distantly re- score, Diane de Poitiers. lated to the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla, From 1924 on he also composed a good deal had studied piano at the Paris Conservatoire and of incidental music for dramatic productions, encouraged his musical education as a child. a natural intersection of his double-threat He was drawn to both music and the theater, background in music and theater, and it was but his first professional steps after high school one such project that gave rise to Trois pièces were hardly distinguished: he started working as brèves. The play was the five-act comedy The a movie-hall pianist and writing popular songs Beaux’s Stratagem, by Irish author George under the pseudonym William Berty. -

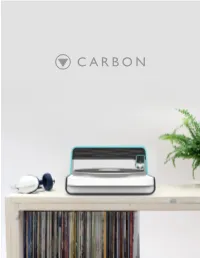

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value in Recorded Music

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value In Recorded Music MFA Advanced Product Design Degree Project Report June 2015 Christopher Wright Canada www.cllw.co TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 - Introduction Introduction 06 The Problem With Streaming 08 The Vinyl Revival 10 The Project 12 Part 2 - Research Record Sales Statistics 16 Music Consumption Trends 18 Vinyl Pros and Cons 20 How Records Are Made 22 Vinyl Pressing Prices 24 Mastering Lathes 26 Historical Review 28 Competitive Analysis 30 Abstract Digital Record Experiments 32 Analogous Research 34 Vinyl records have re-emerged as the preferred format for music fans and artists Part 3 - Field Research alike. The problem is that producing vinyl Research Trip - Toronto 38 records is slow and expensive; this makes it Expert Interviews 40 difcult for up-and-coming artists to release User Interviews 44 their music on vinyl. What if you could Extreme User Interview 48 make your own records at home? Part 4 - Analysis Research Analysis 52 User Insights 54 User Needs Analysis 56 Personas 58 Use Environment 62 Special Thanks To: Technology Analysis 64 Product Analysis 66 Anders Smith Thomas Degn Part 5 - Strategy Warren Schierling Design Opportunity 70 George Graves & Lacquer Channel Goals & Wishes 72 Tyler Macdonald Target Market 74 My APD 2 classmates and the UID crew Inspiration & Design Principles 76 Part 6 - Design Process Initial Sketch Exploration 80 Sacrificial Concepts 82 Concept Development 84 Final Direction 94 Part 7 - Result Final Design 98 Features and Details 100 Carbon Cut App 104 Cutter-Head Details 106 Mechanical Design 108 Conclusions & Reflections 112 References 114 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 4 5 INTRODUCTION Personal Interest I have always been a music lover; I began playing in bands when I was 14, and decided in my later teenage years that I would pursue a career in music. -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year US/\ and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Aust1alasia and far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Lionel Carley 131\, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon l Iandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard I Iickox FRCO (CHM) Lyndon Jenkins Tasmin Little f CSM, ARCM (I Ions), I Jon D. Lilt, DipCSM Si1 Charles Mackerras CBE Rodney Meadows Robc1 t Threlfall Chain11a11 Roge1 J. Buckley Trcaswc1 a11d M11111/Jrrship Src!l'taiy Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Jlighgate Road, Walsall, WSl 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: delius(alukonlinc.co.uk Serirta1y Squadron Lcade1 Anthony Lindsey l The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex P021 3SR 'fol: 01243 824964 Editor Jane Armour-Chclu 17 Forest Close, Shawbirch, 'IC!ford, Shropshire TFS OLA Tel: 01952 408726 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.dclius.org.uk Emnil: [email protected]. uk ISSN-0306-0373 Ch<lit man's Message............................................................................... 5 Edilot ial....................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 6 ARTICLES BJigg Fair, by Robert Matthew Walker................................................ 7 Frede1ick Delius and Alf1cd Sisley, by Ray Inkslcr........... .................. 30 Limpsficld Revisited, by Stewart Winstanley....................................... 35 A Forgotten Ballet ?, by Jane Armour-Chclu -

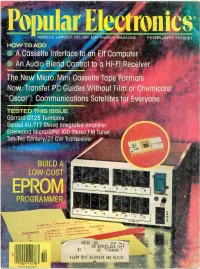

HOW TO, D, °;;Ti

11 ° . i WORLDS LARGEST- SELLING'.,ÉLECTRONICS-MÁGÁZIh'Ee FEBRUARY 1978/$1 : °;;ti. T ° HOW TO, D, , .. rA Cá sette.71n arfacé tó On Elf Computer r ° - II' An_:.Átió'Blélrid-__,. ..tÁ.Coritról;to 'a- Hi -Fi Receiver - .,, The .V .1w: MicroMini Cassette Tape áfis ,Forx PC Guides Without Film or Ch micals! \\, ,0scar'scan: : 'Communications Satellites forr;Eyeryoné 1 , TESTÉD.T1-11S: ISSUE :Gárrard GT25 Turntable 1.',/({Sánsü-iAU-717.Stereó: Integrated Amplifier Slierwoód= Micro/CPU 100 Stereo FM Tuner Téñ;.Tec Century/21 CW Transce,iyer.,. 9' o _ L, 4Y-4: 50 , . 1. 4 3 ' 2 ADDRESS -- PROGRAMMER . 7 B r` P t'efi.. O 2 ' E LCPg= R w51"e"1- ,P ola 4,» °C. 41. I />FD°5 oo.ij v0 de> oldr .e>' oat, p 0 I 6 Z r`16 . V:y -nu; n.1 aa a0on311atiN Os79 Z0 ar 1130I11VO 1 . , - 6/MIN 01.411 060W05+9 961í0E of 14024 14278 ee ° Popular Electro rocs AmericanRadioHistory.Com Introducing the mobile that can move And ike all Cobras it comes equipped you out of the world of the ordinary with such standard features as an easy - and into the world of the serious CB'er. to -read LED channel indicator. The Cobra 138XLR Single Sideband. Switchable noise blanking and limiting. Sidebanding puts - p An RF/signal strength meter. And you in your own I SB LSr Cobra's exclusive DynaMike gain control. private world. A - d ' You'll find the 138XLR SSB wherever world where there's Cobras are sold. Wnich is almost every- less congestion. -

Guidelines for Audiovisual and Multimedia Collection Management

DRAFT ONLY Guidelines for Audiovisual and Multimedia Collection Management in Libraries Revised by: Sonia Gherdevich Senior Manager, Collection Stewardship National Film and Sound Archive of Australia [email protected] with contributions from the Audiovisual and Multimedia Section Standing Committee Supersedes: Guidelines for Audiovisual and Multimedia materials in libraries and other institutions /Bruce Royan, Monika Cremer et al for the IFLA Audiovisual and Multimedia Section. The Hague, IFLA Headquarters, 2004. – 21p. 30 cm. – (IFLA Professional Reports : 80) Language: English DRAFT ONLY DRAFT ONLY TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD i 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Key Definitions 2 1.4 Professional Associations 3 PART A MANAGEMENT OF AUDIOVISUAL COLLECTIONS A-1 Acquisitions 4 A-2 Cataloguing 5-6 A-3 Access 6 A-4 Rights 6 A-5 Disaster Recovery Management 7 A-6 Staff Skills 7 A-7 Budget 8 PART B PHYSICAL FORMATS B-1 Format Types 9 B-2 Packaging 9-10 B-3 Preservation 10-11 B-4 Storage 11-12 PART C DIGITAL FORMATS C-1 Born-Digital Collection Works 13 C-2 Infrastructure and Systems 13 C-3 Preservation 14 C-4 Storage 14 Attachment A Professional Associations 15 Attachment B Cataloguing Standards 16 Attachment C Physical Audiovisual and Multimedia Carriers 17-19 Attachment D Preservation Standards for Digitising Audiovisual Works 20-21 Attachment E Storage Standards and Best Practices for Audiovisual Works 22-25 DRAFT ONLY DRAFT ONLY FOREWORD This set of Guidelines updates the IFLA Audiovisual and Multimedia Section (AVMS) Guidelines document originally developed and shared in 1982 and updated in 2003.