University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

International Society of Barristers Quarterly

International Society of Barristers Volume 52 Number 1 UNFINISHED BUSINESS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE QUEST FOR THE RECOVERY OF NAZI-LOOTED ART Donald Burris WHOSE ART IS IT, ANYWAY? E. Randol Schoenberg DEMOCRACY IN THE BALANCE: THE ESSENTIAL ROLE OF DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND NORMS Sally Yates MAGNANIMITAS: THE WONDER OF YOU AND THE POWER OF THE TEAM Bill Curry Quarterly Annual MeetIngs 2020: March 22–28, The Sanctuary at Kiawah Island, Kiawah Island, South Carolina 2021: April 25–30, The Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin, Ireland International Society of Barristers Quarterly Volume 52 2019 Number 1 CONTENTS Unfinished Business of the Twentieth Century: The Quest for the Recovery of Nazi-looted Art . 1 Donald Burris Whose Art Is It, Anyway? . 35 E. Randol Schoenberg Democracy in the Balance: The Essential Role of Democratic Institutions and Norms . 41 Sally Yates Magnanimitas: The Wonder of You and the Power of the Team . 53 Bill Curry i International Society of Barristers Quarterly Editor Donald H. Beskind Associate Editor Joan Ames Magat Editorial Advisory Board Daniel J. Kelly J. Kenneth McEwan, ex officio Editorial Office Duke University School of Law Box 90360 Durham, North Carolina 27708-0360 Telephone (919) 613-7085 Fax (919) 613-7231 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 52 Issue Number 1 2019 The INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BARRISTERS QUARTERLY (USPS 0074-970) (ISSN 0020- 8752) is published quarterly by the International Society of Barristers, Duke University School of Law, Box 90360, Durham, NC, 27708-0360. Periodicals postage is paid in Durham and additional mailing offices. Subscription rate: $10 per year. Back issues and volumes through Volume 44 available from William S. -

Getting Creative About Development

Atlantic Council AFRICA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Getting Creative About Development SEPTEMBER 2018 AUBREY HRUBY y 2035, sub-Saharan Africa will have more working-age people than the rest of the world combined. African governments col- lectively need to create eighteen million new jobs each year to absorb the large, young, and ambitious population coming to Bworking age.1 But technological advances, combined with the underde- veloped infrastructure of most African nations, mean that the tried and true model of export-oriented industrialization, which allowed the East and Southeast Asian economies to develop very rapidly, is unlikely to produce adequate job creation in the vast majority of African markets. In fact, manufacturing as a share of total economic activity in Africa has stagnated at about 10 percent,2 and—though there are notable excep- tions, such as Ethiopia—the continent as a whole is deindustrializing.3 Agriculture still continues to serve as the backbone of most African economies, with over 70 percent of Africans earning a living in that sector.4 But as Africa urbanizes, the composition of economic activity is rap- idly changing, shifting away from agriculture and towards the services sector. In 2015, services accounted for 58 percent of sub-Saharan GDP (up from 47 percent in 2005).5 More significantly, 33 percent of African 1 Céline Allard et al., Regional Economic Outlook: sub-Saharan Africa 2015, Internation- al Monetary Fund, April 2015, https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/import- ed-flagship-issues/external/pubs/ft/reo/2015/afr/eng/pdf/_sreo0415pdf.ashx. 2 Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly, “Africa’s Alternative Path to Development,” The Brook- ings Institution, May 3, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/africas-alterna- tive-path-to-development/. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Benny Page to Release New Single Champion Sound

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BENNY PAGE TO RELEASE NEW SINGLE CHAMPION SOUND Artist: Benny Page Release: Champion Sound ft. Assassin Date: August 2014 “If you don't know about Benny Page…make sure you get to know.... We are loving the sound of this” MOBO Awards (Official) “Benny Page is going to be a complete tear down” Glastonbury Festivals “This tune is massive!” BBC Radio One In the lead up to his debut Glastonbury Festival appearance headlining The Cave, Benny Page announces his new single entitled Champion Sound, out worldwide August 2014 on his own label High Culture Recordings and Rise Artists Ltd. This release is revealed after Mistajams recent BBC Radio premiere, an accolade following the wave of success surrounding his recent dancefloor hit Hot Body Gal ft. Richie Loop supported Sir David Rodigan, Seani B and Toddla T across BBC Radio One, 1Xtra and Kiss Fm alongside worldwide festival and club appearances. Champion Sound features Assassin who appears on Kanye West’s last album “Yeezus” and was mastered at Metropolis Studios by Stuart Hawkes who has worked with Basement Jaxx, Rudimental, Disclosure, Example and Maverick Sabre to name a few. After number of years establishing international recognition; Benny Page has honed his sound initiating the start of this unique album project. Flying over to Jamaica to work personally with prestigious artists in the area, Benny Page teamed up with Richie Loop on his first single for the project entitled Hot Body Gal, the follow up Champion Sound also features a Jamaican front man called Assassin. He recorded a range of artists on the island with a goal to achieve a more authentic and diverse sound, going through the motions of a more traditional and personal songwriting process managing the studio recordings directly. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Artist Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 00321,15543 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10942 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 05969 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 06024 10cc Donna 03724 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 03126 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 03613 10cc I'm Not In Love 11450,14336 10cc Rubber Bullets 03529 10cc Things We Do For Love, The 14501 112 Dance With Me 09860 112 Peaches & Cream 09796 112 Right Here For You 05387 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 05373 112 & Super Cat Na Na Na 05357 12 Stones Far Away 12529 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 04207 2 Brothers On 4th Come Take My Hand 02283 2 Evisa Oh La La La 03958 2 Pac Dear Mama 11040 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 05393 2 Pac & Eric Will Do For Love 01942 2 Unlimited No Limits 02287,03057 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 04201 3 Colours Red Beautiful Day 04126 3 Doors Down Be Like That 06336,09674,14734 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 09625 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 02103,07341,08699,14118,17278 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 05609,05779 3 Doors Down Loser 07769,09572 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 10448 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 06477,10130,15151 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 07992 311 All Mixed Up 14627 311 Amber 05175,09884 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 05267 311 Creatures (For A While) 05243 311 First Straw 05493 311 I'll Be Here A While 09712 311 Love Song 12824 311 You Wouldn't Believe 09684 38 Special If I'd Been The One 01399 38 Special Second Chance 16644 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 05043 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 09798 3LW Playas Gon' Play -

CLIMATE CHANGE, NEOLIBERALISM and the FUTURE of the ARCTIC Avi Brisman1

NOT A BEDTIME STORY: CLIMATE CHANGE, NEOLIBERALISM AND THE FUTURE OF THE ARCTIC Avi Brisman1 I. INTRODUCTION............................................................ 242 II. WHEN SANTA TURNS GREEN AND OUR CHILDREN’S ENGAGEMENT WITH ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS .... 265 III. NEO-LIBERALISM AND NATIONAL, STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT RESPONSIBILITY TO ACT ..................... 271 IV. TOWARDS A BETTER PORTRAYAL OF THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT IN CHILDREN’S STORIES AND LITERATURE ............................................................... 285 1 MFA, JD, PhD, Assistant Professor School of Justice Studies, College of Justice and Safety, Eastern Kentucky University, 521 Lancaster Avenue, 467 Stratton, Richmond, KY 40475. This Article has been adapted from a number of lectures and papers delivered during the Spring 2013 and Fall 2013 terms: (1) Avi Brisman, Climate Change and the Future of the Arctic: Cultural and Environmental Considerations. Paper presented at “Battle for the North: Is All Quiet on the Arctic Front?” Michigan State University International Law Review Annual Symposium, East Lansing, MI, 21 February 2013; (2) Avi Brisman, Judah Schept, and Tyler Wall, Future Directions in Critical Criminology. Panel discussion, Graduate Student Colloquium, Co-sponsored by the Center for the Study of Social Justice and the Department of Sociology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, 3 April 2013; (3) Avi Brisman, Climate Change: Not a Bedtime Story. Brown bag talk given to the Criminal Justice Graduate Student Association, School of Justice Studies, College of Justice and Safety, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY, 25 April 2013; (4) Avi Brisman, Apocalypse Soon? From Ecocide to Misericordia to the End of the World. Seminar talk, Essex Sustainability Institute, University of Essex (Colchester Campus), Colchester, United Kingdom, 21 May 2013; and (5) Avi Brisman, Apocalypse Soon? Ecocidal Tendencies, Misericordia and the End of the World (As We Know It). -

Special Issues

FOR WEEK ENDING JANUARY 20, 1990 Billboard Billboard. Hot Black Singles SALES & AIRPLAYTM A ranking of the top 40 black singles by sales and airplay. respectively, with reference to each title's composite position on the main Hot Black Singles chart. SALES § AIRPLAY m5 TITLE ARTIST g TITLE ARTIST g 1 3 ILL BE GOOD TO YOU QUINCY 1 1 2 JONES I'LL BE GOOD TO YOU QUINCY JONES 1 SPECIAL 4 ISSUES 2 LET'S GET IT ON BY ALL MEANS 3 2 5 MAKE IT LIKE IT WAS REGINA BELLE 2 3 9 MAKE IT LIKE IT WAS REGINA BELLE 2 3 6 SILKY SOUL MAZE FEATURING FRANKIE BEVERLY 4 4 5 PUMP UP THE JAM TECHNOTRONIC FEATURING FELLY 11 4 4 LET'S GET IT ON BY ALL MEANS 3 SPOTLIGHT ISSUE IN THIS SECTION AD DEADLINE 5 1 RHYTHM NATION JANET JACKSON 5 5 10 WALK ON BY SYBIL 8 6 6 SILKY SOUL MAZE FEATURING FRANKIE BEVERLY 4 6 8 I WANNA BE RICH CALLOWAY 10 7 10 REAL LOVE SKYY 6 7 11 REAL LOVE SKYY 6 8 12 ALL NITE 7 7 ENTOUCH FEATURING KEITH SWEAT 8 ALL NITE ENTOUCH FEATURING KEITH SWEAT 7 ART Feb 17 Art At 30 Jan 23 9 14 HOLD ME SERIOUS ON O'JAYS 9 9 1 RHYTHM NATION JANET JACKSON 5 LABOE History 10 13 WALK ON BY SYBIL 8 10 9 SERIOUS HOLD ON ME O'JAYS 9 11 11 TURN IT OUT ROB BASE 17 11 13 SPECIAL THE TEMPTATIONS 14 30TH Oldies 12 2 TENDER LOVER BABYFACE 13 12 15 YOUR SWEETNESS GOOD GIRLS 15 Newies 13 20 f WANNA BE RICH CALLOWAY 10 13 18 SCANDALOUS! PRINCE 12 14 27 SCANDALOUS! PRINCE 12 14 17 NO FRIEND OF MINE CLUB NOUVEAU 16 15 21 NO FRIEND OF MINE CLUB NOUVEAU 16 15 16 SHOULD HAVE BEEN YOU MICHAEL COOPER 21 JOHNNY Feb 24 The Man Jan 30 16 29 40 MORE LIES MICHELLE 18 16 3 TENDER LOVER -

The Audio Mixer As Creative Tool in Musical Composition and Performance

Die Reihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” stellt Arbeiten des Instituts fur¨ Elektronische Musik und Akustik Graz zu den Themenbereichen Akustik, Com- putermusik, Musikelektronik und Medienphilosophie vor. Dabei handelt es sich meist um Ergebnisse von Forschungsarbeiten am Institut oder um uberarbeitete¨ Vortrage¨ von InstitutsmitarbeiterInnen. Daruber¨ hinaus soll hier eine Diskussionsplattform zu den genannten Themen entstehen. Beitrage¨ konnen¨ auch eine Beschreibung von Projekten und Ideen sein, die sich in Entwicklung befinden und noch nicht fertiggestellt sind. Wir hoffen, dass die Schriftreihe “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” eine An- regung fur¨ Ihre wissenschaftliche und kunstlerische¨ Arbeit bietet. Alois Sontacchi (Herausgeber) The series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” (contributions to electronic music) presents papers by the Institute of Electronic Music Graz on various topics inclu- ding acoustics, computer music, music electronics and media philosophy. The contributions present results of research performed at the institute or edited lec- tures held by members of the institute. The series shall establish a discussion forum for the above mentioned fields. Ar- ticles should be written in English or German. The contributions can also deal with the description of projects and ideas that are still in preparation and not yet completed. We hope that the series “Beitrage¨ zur Elektronischen Musik” will provide thought- provoking ideas for your scientific and artistic work. Alois Sontacchi (editor) The audio mixer as -

An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear

How to Write Songs That Sell _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear By Anthony Ceseri This is NOT a free e-book! You have been given one copy to keep on your computer. You may print out one copy only for your use. Printing out more than one copy, or distributing it electronically is prohibited by international and U.S.A. copyright laws and treaties, and would subject the purchaser to expensive penalties. It is illegal to copy, distribute, or create derivative works from this book in whole or in part, or to contribute to the copying, distribution, or creating of derivative works of this book. Furthermore, by reading this book you understand that the information contained within this book is a series of opinions and this book should be used for personal entertainment purposes only. None of what’s presented in this book is to be considered legal or personal advice. Published by: Success For Your Songs Visit us on the web at: http://www.SuccessForYourSongs.com Copyright © 2012 by Success For Your Songs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. How to Write Songs That Sell 3 Table of Contents Introduction 6 The Methods 8 Special Report 9 Module 1: The Big -

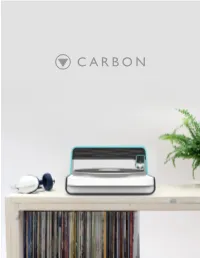

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value in Recorded Music

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value In Recorded Music MFA Advanced Product Design Degree Project Report June 2015 Christopher Wright Canada www.cllw.co TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 - Introduction Introduction 06 The Problem With Streaming 08 The Vinyl Revival 10 The Project 12 Part 2 - Research Record Sales Statistics 16 Music Consumption Trends 18 Vinyl Pros and Cons 20 How Records Are Made 22 Vinyl Pressing Prices 24 Mastering Lathes 26 Historical Review 28 Competitive Analysis 30 Abstract Digital Record Experiments 32 Analogous Research 34 Vinyl records have re-emerged as the preferred format for music fans and artists Part 3 - Field Research alike. The problem is that producing vinyl Research Trip - Toronto 38 records is slow and expensive; this makes it Expert Interviews 40 difcult for up-and-coming artists to release User Interviews 44 their music on vinyl. What if you could Extreme User Interview 48 make your own records at home? Part 4 - Analysis Research Analysis 52 User Insights 54 User Needs Analysis 56 Personas 58 Use Environment 62 Special Thanks To: Technology Analysis 64 Product Analysis 66 Anders Smith Thomas Degn Part 5 - Strategy Warren Schierling Design Opportunity 70 George Graves & Lacquer Channel Goals & Wishes 72 Tyler Macdonald Target Market 74 My APD 2 classmates and the UID crew Inspiration & Design Principles 76 Part 6 - Design Process Initial Sketch Exploration 80 Sacrificial Concepts 82 Concept Development 84 Final Direction 94 Part 7 - Result Final Design 98 Features and Details 100 Carbon Cut App 104 Cutter-Head Details 106 Mechanical Design 108 Conclusions & Reflections 112 References 114 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 4 5 INTRODUCTION Personal Interest I have always been a music lover; I began playing in bands when I was 14, and decided in my later teenage years that I would pursue a career in music. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.