Contested Nation: Freedman and the Cherokee Nation Dave Watt Illinois State University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cherokee Genealogy Resource Presentation

FindingFinding youryour CherokeeCherokee AncestorsAncestors ““MyMy GrandmotherGrandmother waswas aa CherokeeCherokee Princess!Princess! ”” WhereWhere toto begin?begin? Information to collect: Names (including maiden names of females) Date and place of birth Date and place of marriage Date and place of death Names of siblings (i.e., brothers and sisters) and Rolls and Roll Numbers SampleSample IndividualIndividual InformationInformation Name:Name: WilliamWilliam CoxCox Born:Born: 77--JuneJune --18941894 inin DelawareDelaware Dist,Dist, CherokeeCherokee NationNation Married:Married: 1515 --OctoberOctober --19191919 inin BlountBlount County,County, TennesseeTennessee toto PollyPolly MorrisMorris Died:Died: 33--AprilApril --19731973 inin Nashville,Nashville, TennesseeTennessee RollRoll // CensusCensus Information:Information: 18961896 CensusCensus // DelawareDelaware DistDist -- RollRoll #517#517 BirthBirth RecordsRecords Oklahoma birth records have been kept since 1925 and are availab le from: Division of Vital Records Oklahoma State Dept. of Health 100 NE 10th Ave PO Box 53551 Oklahoma City, OK 73152 -3551 NOTE: Before 1947, all birth records are filed under the father' s name. After 1947, all birth records are filed under the child's name. Birth Affidavits for Minor Cherokees born (1902 to 1906) were in cluded in the Dawes Applications, and are available from: Oklahoma Historical Society 2401 N Laird Oklahoma City, OK 73105 -4997 Guion Miller Applications also include birthdates and proof of family relationships. These are available -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Notice: study guide will be updated after the December general election. Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

Chickamauga Names

Chickamaugas / Dragging Canoe Submitted by Nonie Webb CHICKAMAUGAS Associated with Dragging Canoe ARCHIE, John Running Water Town – trader in 1777. BADGER “Occunna” Said to be Attakullakullas son. BENGE, Bob “Bench” b. 1760 Overhills. D. 1794 Virginia. Son of John Benge. Said to be Old Tassels nephew. Worked with Shawnees, and Dragging Canoe. BENGE, John Father of Bob Benge. White trader. Friend of Dragging Canoe. BENGE, Lucy 1776-1848 Wife of George Lowry. BIG FELLOW Worked with John Watts ca. 1792. BIG FOOL One of the head men of Chicamauga Town. BLACK FOX “Enola” Principal Headman of Cherokee Nation in 1819. Nephew to Dragging Canoe. BLOODY FELLOW “Nentooyah” Worked with Dragging Canoe BOB Slave Owner part of Chicamaugas. (Friend of Istillicha and Cat) BOOT “Chulcoah” Chickamauga. BOWL “Bold Hunter” or “Duwali” Running Water Town. b. 1756l- Red hair – blue eyes. Father was Scott. Mother was Cherokee.1768 d, Texas. (3 wives) Jennie, Oolootsa, & Ootiya. Headman Chickamaugas. BREATH “Untita” or Long Winded. Headman of Nickajack Town. d. Ore’s raid in 1794. 1 Chickamaugas / Dragging Canoe Submitted by Nonie Webb BROOM. (see Renatus Hicks) BROWN, James Killed by Chickamaugas on [Murder of Brown Family]….Tennessee River in 1788. Wife captured. Some of Sons and Son in Laws Killed. Joseph Brown captured. Later Joseph led Ore’s raid on Nickajack & Running Water Town in 1794. (Brown family from Pendleton District, S. C.) BROWN, Thomas Recruited Tories to join Chickamaugas. Friend of John McDonald. CAMERON, Alexander. “Scotchee” Dragging Canoe adopted him as his “brother”. Organized band of Torries to Work with the Chicamaugas. CAMPBELL, Alexander. -

The Life and Work of Sophia Sawyer, 19Th Century Missionary and Teacher Among the Cherokees Teri L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 "Behold Me and This Great Babylon I Have Built": The Life and Work of Sophia Sawyer, 19th Century Missionary and Teacher Among the Cherokees Teri L. Castelow Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION "BEHOLD ME AND THIS GREAT BABYLON I HAVE BUILT": THE LIFE AND WORK OF SOPHIA SAWYER, 19TH CENTURY MISSIONARY AND TEACHER AMONG THE CHEROKEES By TERI L. CASTELOW A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Teri L. Castelow defended on August 12, 2004. ______________________________ Victoria Maria MacDonald Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Elna Green Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Sande Milton Committee Member ______________________________ Emanuel Shargel Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Carolyn Herrington, Chair, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies ___________________________________ Richard Kunkel, Dean, College of Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the assistance of several people for their support over the extended period it took to complete the degree requirements and dissertation for my Doctor of Philosophy degree. I would like to thank the many friends and family who have offered encouragement along the way and who did not criticize me for being a perpetual student. My parents, Paul and Nora Peasley, provided moral support and encouragement, as well as occasional child-care so I could complete research and dissertation chapters. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA the CHEROKEE NATION, Plaintiff

Case 1:13-cv-01313-TFH Document 248 Filed 08/30/17 Page 1 of 78 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA THE CHEROKEE NATION, Plaintiff/ Counter Defendant, v. RAYMOND NASH, et al., Defendants/ Counter Claimants/ Cross Claimants, --and-- Civil Action No. 13-01313 (TFH) MARILYN VANN, et al., Intervenor Defendants/ Counter Claimants/ Cross Claimants, --and-- RYAN ZINKE, SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR, AND THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, Counter Claimants/ Cross Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION Although it is a grievous axiom of American history that the Cherokee Nation’s narrative is steeped in sorrow as a result of United States governmental policies that marginalized Native American Case 1:13-cv-01313-TFH Document 248 Filed 08/30/17 Page 2 of 78 Indians and removed them from their lands,1 it is, perhaps, lesser known that both nations’ chronicles share the shameful taint of African slavery.2 This lawsuit harkens back a century-and-a-half ago to a treaty entered into between the United States and the Cherokee Nation in the aftermath of the Civil War. In that treaty, the Cherokee Nation promised that “never here-after shall either slavery or involuntary servitude exist in their nation” and “all freedmen who have been liberated by voluntary act of their former owners or by law, as well as all free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months, and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees . -

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

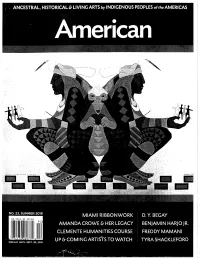

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

These Hills, This Trail: Cherokee Outdoor Historical Drama and The

THESE HILLS, THIS TRAIL: CHEROKEE OUTDOOR HISTORICAL DRAMA AND THE POWER OF CHANGE/CHANGE OF POWER by CHARLES ADRON FARRIS III (Under the Direction of Marla Carlson and Jace Weaver) ABSTRACT This dissertation compares the historical development of the Cherokee Historical Association’s (CHA) Unto These Hills (1950) in Cherokee, North Carolina, and the Cherokee Heritage Center’s (CHC) The Trail of Tears (1968) in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears were originally commissioned to commemorate the survivability of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and the Cherokee Nation (CN) in light of nineteenth- century Euramerican acts of deracination and transculturation. Kermit Hunter, a white southern American playwright, wrote both dramas to attract tourists to the locations of two of America’s greatest events. Hunter’s scripts are littered, however, with misleading historical narratives that tend to indulge Euramerican jingoistic sympathies rather than commemorate the Cherokees’ survivability. It wasn’t until 2006/1995 that the CHA in North Carolina and the CHC in Oklahoma proactively shelved Hunter’s dramas, replacing them with historically “accurate” and culturally sensitive versions. Since the initial shelving of Hunter’s scripts, Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears have undergone substantial changes, almost on a yearly basis. Artists have worked to correct the romanticized notions of Cherokee-Euramerican history in the dramas, replacing problematic information with more accurate and culturally specific material. Such modification has been and continues to be a tricky endeavor: the process of improvement has triggered mixed reviews from touristic audiences and from within Cherokee communities themselves. -

Becoming Indian

BECOMING INDIAN The Struggle over Cherokee Identity in the Twenty-first Century one Opening Often when we are about to leave a place, we find out what really matters, what peo- ple care about, what rattles around inside their hearts. So it was for me at the end of fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in Tahlequah, Oklahoma—the heart of the Cherokee Nation—where I lived in 1995 and 1996 and where I have returned on a regular basis ever since. On the eve of my first departure, a number of Cherokee peo- ple, particularly tribal employees, started directing my attention toward an intriguing and at times disturbing phenomenon. This is how in late April 1996 I found myself screening a video with five Cherokee Nation employees, two of whom worked in the executive offices, the others for the Cherokee Advocate, the official tribal newspaper.1 Several of them had insisted that if I was going to write about Cherokee identity pol- itics,2 I needed to see this particular video. A woman from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina had shot the original footage, having traveled all the way to Portsmouth, Ohio, in July 1987 to record the unusual proceedings. The images she captured were so powerful that tribal employees in Oklahoma and North Carolina were still expressing confusion and resentment almost a decade later. Though it was in terrible shape from repeated dubbing, the video gripped our attention. Not only had it been shot surreptitiously, with the novice filmmaker and her companion posing as news reporters, but also our version was a copy of a copy of a copy that had been passed hand to hand, like some weird Grateful Dead bootleg, www.sarpress.sarweb.org 1 making its way through Indian country from the eastern seaboard to the lower Midwest. -

AISES Leadership Summit

2019 March 14-16 Cherokee, North Carolina Harrah’s Cherokee Hotel and Casino http://summit.aises.org #AISES #AISESLS19 2019 AISES Leadership Summit 2 2019 AISES Leadership Summit CONTENTS 4 Welcome Letter 5 Opening Reception Entertainment 6 Summit Sponsors 7 Safe Camp and Code of Conduct 8 AISES Leadership Summit Description 9 Opening Welcome Speaker 10 Agenda 13 Venue Map 14 Session Descriptions 20 Presenters 26 AISES Executive Commitee 26 AISES Board of Directors 26 AISES Student Representatives 27 Advisory Councils and Chairs 28 Council of Elders 28 Student Representatives 29 AISES Staff 3 2019 AISES Leadership Summit 4 2019 AISES Leadership Summit Cherokee ᏣᎳᎩ Songs ᏗᎧᏃᎩᏛ and ᏃᎴ Dances ᏓᎾᎳᏍᎩᏍᎬ During the opening ceremony of the 2019 AISES Leadership Summit, the Cherokee Youth Council (CYC) will be performing two Cherokee traditional social dances. The Cherokee Youth Council is a culturally-based leadership program for Eastern Band Cherokee youth in grades 7-12. This program is housed under the Ray Kinsland Leadership Institute at the Cherokee Boys Club and is funded by the Cherokee Preservation Foundation. The mission of the Ray Kinsland Leadership Institute is to create a community of selfless leaders deeply rooted in Cherokee culture. The CYC have chosen to demonstrate the Buffalo Dance and the Friendship Dance. Cherokee social dances involve men, women, and children of all ages. During the dances the dancers line up male, female, male, female and step in sync with the drum or rattle, utilized by the male singer. Historically, there were small bison native to the Southeastern United States and the Buffalo Dance was traditionally done to honor the buffalo and thank the animal for providing meat, tools, and fur for Cherokee survival. -

Cherokee Freedmen: the Struggle for Citizenship

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 Cherokee Freedmen: The trS uggle for Citizenship Bethany Hope Henry University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Henry, Bethany Hope, "Cherokee Freedmen: The trS uggle for Citizenship" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 2345. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cherokee Freedmen: The Struggle for Citizenship Cherokee Freedmen: The Struggle for Citizenship A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Bethany Hope Henry University of Missouri Bachelor of Arts in History, 2012 Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology, 2012 May 2014 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Dr. Daniel Sutherland Thesis Director Dr. Elliott West Dr. Andrea Arrington Committee Member Committee Member Dr. Jeannie Whayne Committee Member Abstract In 2011, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court voted to exclude freedmen (descendants of former slaves) from voting, overturning a constitutional amendment that gave freedmen tribal rights. Cherokee freedmen argue that the Cherokee Nation is ignoring the Treaty of 1866 which granted all freedmen “rights as Cherokee citizens”, and they call upon federal support to redeem their rights as equals. -

Proliolems of Cherokee Children. an Extensive History of the Cherokee Nation Is Included

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 029 741 RC 003 452 By-Wax. Murray L.: And Others Indian Education in Eastern Oklahoma. A Report of Fieldwork Among the Cherokee. Final Report. Kansas Univ.. Lawrence. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No-BR-5-0565 Pub Date Jan 69 Contract- OEC-6-10-260 Note- 276p. EDRS Price MF-$1.25 HC-$13.90 Descriptors" AmericanIndianCulture. American IndianLanguages. CultoreConflict,Economically Disadvantaged. Educational Disadvantagement EducationalDiscrimination. English (Second Language). Minority Group Teachers, Parent School Relationship. Rural Family. Values Identifiers- Cherokees. Oklahoma A field study of Cherokee Indians in Eastern Oklahoma revealed the following information: (1) educators were ignorant of and indifferent to the language. values. and cultural traditions of the Tribal (rural) Cherokee: (2) the Tribal Cherokees were an impoverished people: (3) both adults and children were educationally disadvantaged: and (4) Tribal Cherokee parents desired that their children obtain an education, but were critical of the schoolsfor abusing their children. Recommendations included: (1) both English and Cherokee be officially recognized: (2) curricula be developed to teach English as a second language: (3) teachers of Cherokee children learn the language and culture of the Cherokee: and (4) special funds be allocated to study the proliolems of Cherokee children. An extensive history of the Cherokee Nation is included. (RH) FINAL REPORT Contract No. 0E-6-10-260 L- Bureau No. 5-0565-2-12-1 f;7 C op INDIAN EDUCATION IN EASTERN OKLAHOMA Murray L. Wax Professor of Sociology The University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 66044 January 1969 U.S. -

Proposed Finding

Proposed Finding Against Acknowledgment of The Central Band ofCherokee (Petitioner #227) Prepared in Response to the Petition Submitted to the Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs for Federal Acknowledgment as an Indian Tribe AUG 06 2010 (Date) Larry Echo Hawk Assistant Secretary Indian Affairs TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS and ACRONYMS .............................................................................. ii INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures Historical Overview .......................................................................3 Administrative History of the Petitioner ..............................................................................4 Historical Overview .............................................................................................................5 Petitioner’s Membership Criteria in its Governing document .............................................6 OFA’s Analysis of the Petitioner’s Membership Criteria ....................................................8 SUMMARY UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7 as Modified by 83.10(e)(1)) ........9 Description of the Petitioner’s Evidence for Descent from the Historical Indian Tribe ...10 Previous Membership Lists................................................................................................10 Current Membership List ...................................................................................................11 Descent Reports