Legal Framework of the Computer Crimes Under the Bulgarian Criminal Law 11 2.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

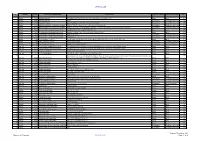

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Transport and Transportation Заочне Навчання

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ХАРКІВСЬКА НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ МІСЬКОГО ГОСПОДАРСТВА Н. І. Видашенко А. В. Сміт TRANSPORT AND TRANSPORTATION Збірник текстів і завдань з дисципліни ‘Іноземна мова ( за професійним спрямуванням ) ( англійська мова)’ (для організації самостійної роботи студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’ спеціальностей 6.050702 – ‘Електричний транспорт ’, ‘Електричні системи комплекси транспортних засобів ’, ‘Електромеханічні системи автоматизації та електропривод ’) Харків – ХНАМГ – 2009 TRANSPORT AND TRANSPORTATION. Збірник текстів і завдань з дисципліни ‘Іноземна мова ( за професійним спрямуванням ) ( англійська мова )’ (для організації самостійної роботи студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’ спеціальностей 6.050702 – ‘Електричний транспорт ’, ‘Електричні системи комплекси транспортних засобів ’, ‘Електромеханічні системи автоматизації та електропривод ’) /Н. І. Видашенко , А. В. Сміт ; Харк . нац . акад . міськ . госп -ва . – Х.: ХНАМГ , 2009. – 60 с. Автори : Н. І. Видашенко , А. В. Cміт Збірник текстів і завдань побудовано за вимогами кредитно -модульної системи організації навчального процесу ( КМСОНП ). Рекомендовано для студентів електромеханічних спеціальностей . Рецензент : доцент кафедри іноземних мов , к. філол . н. Ільєнко О. Л. Затверджено на засіданні кафедри іноземних мов , протокол № 1 від 31 серпня 2009 року © Видашенко Н. І. © Сміт А. В. © ХНАМГ , 2009 2 CONTENTS ВСТУП 4 UNIT ONE. ENGLISH IN OUR LIFE 5 UNIT TWO. HIGHER EDUCATION 17 UNIT THREE. MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION 21 UNIT FOUR. CITY TRAFFIC 40 UNIT FIVE. TYPES OF PAYMENT IN CITY TRAFFIC 47 UNIT SIX. DOUBLED TRANSPORT 52 UNIT SEVEN. BUSES IN LONDON 54 SOURCES 59 3 ВСТУП Даний збірник текстів призначений для студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’, що вивчають англійську мову . -

Rolling Stock Orders: Who

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE HEADLINES l Toronto’s streetcar advocates fight back l UK’s Midland Metro expansion approved l Democrats propose more US light rail ROLLING STOCK ORDERS: WHO... WHAT... HOW MUCH? Ukrainian tramways under the microscope US streetcar trends: Mixed fleets: How technology Lessons from is helping change over a century 75 America’s attitude of experience to urban rail in Budapest APRIL 2012 No. 892 1937–2012 WWW. LRTA . ORG l WWW. TRAMNEWS . NET £3.80 TAUT_April12_Cover.indd 1 28/2/12 09:20:59 TAUT_April12_UITPad.indd 1 28/2/12 12:38:16 Contents The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association 128 News 132 APRIL 2012 Vol. 75 No. 892 Toronto light rail supporters fight back; Final approval for www.tramnews.net Midland Metro expansion; Obama’s budget detailed. EDITORIAL Editor: Simon Johnston 132 Rolling stock orders: Boom before bust? Tel: +44 (0)1832 281131 E-mail: [email protected] With packed order books for the big manufacturers over Eaglethorpe Barns, Warmington, Peterborough PE8 6TJ, UK. the next five years, smaller players are increasing their Associate Editor: Tony Streeter market share. Michael Taplin reports. E-mail: [email protected] 135 Ukraine’s road to Euro 2012 Worldwide Editor: Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. Mike Russell reports on tramway developments and 135 E-mail: [email protected] operations in this former Soviet country. News Editor: John Symons 140 The new environment for streetcars 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

Ukraine Handbook

KIEV, UKRAINE HANDBOOK Military Family Services Europe / MFS(E) Riga-Remote Team [email protected] www.cafconnection.ca / www.connexionfac.ca Date published: 20 June 2017 Date revised: 17 Feb 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GREETINGS FROM YOUR MFS(E) RIGA-REMOTE TEAM 1 EUROPEAN ADVISORY COMMITTEE ............................ 3 USING THIS GUIDE .................................................... 4 SOME HELPFUL RESOURCES ....................................... 1 OVERVIEW OF KIEV ................................................... 2 Maps ............................................................................................................. 2 Geography/Politics .......................................................................................... 4 Climate ......................................................................................................... 4 Languages ..................................................................................................... 4 Religion ......................................................................................................... 5 Cost of Living ................................................................................................. 5 Canadian/Expat Community ............................................................................. 6 Cultural Nuances, Etiquette and Traditions ......................................................... 6 Public Holidays ............................................................................................... 9 News .......................................................................................................... -

Progress Report (2016–2018) of the MDB Working Group On

Progress Report (2016-2018) of the MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport September 2019 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 3 2 MDB ACTION ON SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT: 2016 to 2018....................................... 4 3 SPECIAL FEATURE: MDB ENGAGEMENT IN ROAD SAFETY IMPROVEMENTS .......... 8 ANNEX: LENDING PROJECTS APPROVED BY EACH MDB ................................................11 African Development Bank ................................................................................................11 Asian Development Bank ...................................................................................................13 CAF – Development Bank of Latin America .......................................................................17 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ........................................................19 European Investment Bank ................................................................................................22 Inter-American Development Bank ....................................................................................26 Islamic Development Bank ................................................................................................28 World Bank ........................................................................................................................29 Note: This is a joint document authored by members of the Multilateral Development -

Georesources and Environment Geological Hazards During

International Journal of IJGE 2018 4(4): 187-200 Georesources and Environment http://ijge.camdemia.ca, [email protected] Available at http://ojs.library.dal.ca/ijge Geotechnical Engineering and Construction Geological Hazards During Construction and Operation of Shallow Subway Stations and Tunnels by the Example of the Kharkiv Metro (1968–2018) Viacheslav Iegupov*, Genadiy Strizhelchik, Anna Kupreychyk, Artem Ubiyvovk Department of Geotechnics and Underground Structures, Kharkiv National University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 40 Sumska Street, Kharkiv, Ukraine Abstract: Scientific, technical and practical problems have been considered in relation to geological hazards during construction and operation of metro objects such as shallow subway stations and tunnels. Analysis of five decades of the experience of construction and subsequent operation of the Kharkiv metro in rough engineering and geological conditions by construction of tunnels at shallow depths under the existing urban development allowed detecting and systematizing a set of the most essential adverse conditions, processes and phenomena. The main geological hazards are related to the expansion of quicksands, possibility of “flotation” of the underground structures, barrage effect, subsidence of the soil body by long-term dewatering, undermining of the built-in territories and difficulties by tunneling in technogenic fill-up grounds when crossing ravines and gullies. Most problems occur in the territories with a high groundwater level: geological risks in these areas increase, and serious incidents occur by sudden adverse changes of hydrodynamic conditions. Zones of high, medium and low geological hazards have been identified. Geological hazards have been defined at the section planned for extension of the metro line, for which calculations of the affluent value were made based on the barrage effect of tunnels on the groundwater flow. -

Sustainable Urban Mobility and Public Transport FINAL

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS 1 2 SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS This publication is part of the Transport Trends and Economics Series (WP.5) New York and Geneva, 2015 3 ©2015 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. Email: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations’ publication issued by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Maps and country reports are only for information purposes. ECE/TRANS/245 4 Transport in UNECE The UNECE Sustainable Transport Division is the secretariat of the Inland Transport Committee (ITC) and the ECOSOC Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals. The ITC and its 17 working parties, as well as the ECOSOC Committee and its sub-committees are intergovernmental decision-making bodies that work to improve the daily lives of people and businesses around the world, in measurable ways and with concrete actions, to enhance traffic safety, environmental performance, energy efficiency and the competitiveness of the transport sector. -

Assessment of Access to Essential Outpatient Medicines in Ukraine

Assessment of access to essential outpatient medicines in Ukraine Assessment of access to essential outpatient medicines in Ukraine Abstract WHO recently conducted a survey to assess the availability and cost of a national tracer list of essential medicines in the outpatient sector in Ukraine using a new collection tool – the WHO Essential Medicines and Health Products Price and Availability Monitoring Mobile Application. This tool facilitates rapid and inexpensive data collection at the facility level. The assessment also gathered data for Sustainable Development Goal indicator 3.b.3. A multidimen- sional index was recently introduced by WHO to enable joint assessment of the availability and cost of medicines. The findings are expected to support policy decisions to improve pharmaceutical management in Ukraine and to identify other factors that may improve access to essential medicines. The assessment’s observations show that monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of pricing policies should be carried out on a regular basis to ensure equal access to essential medicines at low cost and, alongside indicators of service coverage and financial protec- tion, to enable the government to track progress towards universal health coverage. Document number: WHO/EURO:2021-2770-42528-59083 © World Health Organization 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. -

The Quest for Natural Gas Pipelines

The quest for natural gas pipelines EU and Eastern Partner energy policies: Security versus transit benefits STUDY EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service and Directorate-General for External Policies Authors: Konur Alp Kocak (EPRS, Members’ Research Service) and Pasquale De Micco, with contribution of Faustine Felici (DG EXPO, Policy Department) July 2016 — PE 586.626 EN This publication aims to provide an overview of the European Union's efforts to maintain gas supply security especially vis-à-vis its main gas supplier, Russia. In that context, Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries, serving either as gas suppliers (Azerbaijan) or transit/corridor countries (all the others except Armenia), have an undeniable role for the EU. Security of gas supply depends on close EU cooperation with its EaP partners and interconnections between them. There are some welcome developments, such as the Southern Gas Corridor that transports Caspian gas to the EU, which reflects the importance of the EaP partners and also contributes to EU energy security and the ambitious Energy Union project. On the other hand, a project aiming to double the capacity of the gas pipeline directly connecting Germany and Russia under the Baltic Sea has raised some criticism. PE 586.626 ISBN 978-92-823-9823-4 doi:10.2861/819912 QA-04-16-606-EN-N Original manuscript, in English, completed in July 2016. The authors acknowledge the graphic support of Eulalia Claros, EPRS. Disclaimer The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the authors and any opinions expressed therein do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. -

METROS/U-BAHN Worldwide

METROS DER WELT/METROS OF THE WORLD STAND:31.12.2020/STATUS:31.12.2020 ّ :جمهورية مرص العرب ّية/ÄGYPTEN/EGYPT/DSCHUMHŪRIYYAT MISR AL-ʿARABIYYA :القاهرة/CAIRO/AL QAHIRAH ( حلوان)HELWAN-( المرج الجديد)LINE 1:NEW EL-MARG 25.12.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmr5zRlqvHY DAR EL-SALAM-SAAD ZAGHLOUL 11:29 (RECHTES SEITENFENSTER/RIGHT WINDOW!) Altamas Mahmud 06.11.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6xG3hZccyg EL-DEMERDASH-SADAT (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 12:29 Mahmoud Bassam ( المنيب)EL MONIB-( ش ربا)LINE 2:SHUBRA 24.11.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UCJA6bVKQ8 GIZA-FAYSAL (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 02:05 Bassem Nagm ( عتابا)ATTABA-( عدىل منصور)LINE 3:ADLY MANSOUR 21.08.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t7m5Z9g39ro EL NOZHA-ADLY MANSOUR (FENSTERBLICKE/WINDOW VIEWS!) 03:49 Hesham Mohamed ALGERIEN/ALGERIA/AL-DSCHUMHŪRĪYA AL-DSCHAZĀ'IRĪYA AD-DĪMŪGRĀTĪYA ASCH- َ /TAGDUDA TAZZAYRIT TAMAGDAYT TAỴERFANT/ الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطيةالشعبية/SCHA'BĪYA ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ : /DZAYER TAMANEỴT/ دزاير/DZAYER/مدينة الجزائر/ALGIER/ALGIERS/MADĪNAT AL DSCHAZĀ'IR ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵏⴻⵖⵜ PLACE DE MARTYRS-( ع ني نعجة)AÏN NAÂDJA/( مركز الحراش)LINE:EL HARRACH CENTRE ( مكان دي مارت بز) 1 ARGENTINIEN/ARGENTINA/REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA: BUENOS AIRES: LINE:LINEA A:PLACA DE MAYO-SAN PEDRITO(SUBTE) 20.02.2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfUmJPEcBd4 PIEDRAS-PLAZA DE MAYO 02:47 Joselitonotion 13.05.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lJAhBo6YlY RIO DE JANEIRO-PUAN 07:27 Así es BUENOS AIRES 4K 04.12.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PoUNwMT2DoI -

A Pipeline Links Russia and Europe a Visit To

A PiPeline links RussiA And euRoPe Castoro sei A VisiT To THe FACToRY sHiP inTerview How imPortanT is RussiAn GAs FoR us? BOMBS AND MINEs dAnGeROUS INHeRiTAnCe FROM TWO WORld wARs A CollAboration bY wiTH Respect. For Europe’s energy needs. Europe needs new sources of natural gas to maintain economic growth while meeting climate protection targets. The Nord Stream Pipeline is a timely and environmentally sound means of bringing large volumes of natural gas to Europe. Nord Stream AG is an international consortium of five major energy companies whose combined experience ensures the best technology, safety and corporate governance for this project. www.nord-stream.com Group GroupGroup Group 2 Nord-StreamDie Pipeline NORD_01_108_Anzeige_SciAm_206x273+3.indd 1 08.09.11 14:46 EDITORIAL Richard Zinken Publishing Director Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH TheDawningofaNewEra—withNaturalGas? Respect. ithnoapparentdestination,thehelicop- moreandmorepeopleseemoderngasandsteam Respect. W ter flies out to sea. But somewhere out combined power plants—especially after the re- there,movingafewkilometersfurthereveryday, actor accident at Fukushima—as an acceptable thereistheCastoro Sei—afloatingfactoryinthe bridgingtechnology. middleoftheBalticSea.Frominsidethisshipthe Butwherewillthesearchforasustainableen- ForFor Europe’sEurope’s Baltic Sea pipeline is being created—gas pipes ergystrategyleadus?Couldourdesireforsecuri- connecting Lubmin in northern Germany with ty of supply result in our being dangerously de- VyborgonRussia’swesterncoast,morethan1,200