Sumerian: the Descendant of a Proto-Historical Creole? an Alternative Approach to The" Sumerian Problem." ROLIG-Papir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

Transparency in Language a Typological Study

Transparency in language A typological study Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration © 2011: Sanne Leufkens – image from the performance ‘Celebration’ ISBN: 978-94-6093-162-8 NUR 616 Copyright © 2015: Sterre Leufkens. All rights reserved. Transparency in language A typological study ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op vrijdag 23 januari 2015, te 10.00 uur door Sterre Cécile Leufkens geboren te Delft Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Hengeveld Copromotor: Dr. N.S.H. Smith Overige leden: Prof. dr. E.O. Aboh Dr. J. Audring Prof. dr. Ö. Dahl Prof. dr. M.E. Keizer Prof. dr. F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen i Acknowledgments When I speak about my PhD project, it appears to cover a time-span of four years, in which I performed a number of actions that resulted in this book. In fact, the limits of the project are not so clear. It started when I first heard about linguistics, and it will end when we all stop thinking about transparency, which hopefully will not be the case any time soon. Moreover, even though I might have spent most time and effort to ‘complete’ this project, it is definitely not just my work. Many people have contributed directly or indirectly, by thinking about transparency, or thinking about me. -

Women in the Ancient Near East: a Sourcebook

WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Women in the Ancient Near East provides a collection of primary sources that further our understanding of women from Mesopotamian and Near Eastern civiliza- tions, from the earliest historical and literary texts in the third millennium BC to the end of Mesopotamian political autonomy in the sixth century BC. This book is a valuable resource for historians of the Near East and for those studying women in the ancient world. It moves beyond simply identifying women in the Near East to attempting to place them in historical and literary context, follow- ing the latest research. A number of literary genres are represented, including myths and epics, proverbs, medical texts, law collections, letters and treaties, as well as building, dedicatory, and funerary inscriptions. Mark W. Chavalas is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, where he has taught since 1989. Among his publications are the edited Emar: The History, Religion, and Culture of a Syrian Town in the Late Bronze Age (1996), Mesopotamia and the Bible (2002), and The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation (2006), and he has had research fellowships at Yale, Harvard, Cornell, Cal-Berkeley, and a number of other universities. He has nine seasons of exca- vation at various Bronze Age sites in Syria, including Tell Ashara/Terqa and Tell Mozan/Urkesh. ROUTLEDGE SOURCEBOOKS FOR THE ANCIENT WORLD HISTORIANS OF ANCIENT ROME, THIRD EDITION Ronald Mellor TRIALS FROM CLASSICAL ATHENS, SECOND EDITION Christopher Carey ANCIENT GREECE, THIRD EDITION Matthew Dillon and Lynda Garland READINGS IN LATE ANTIQUITY, SECOND EDITION Michael Maas GREEK AND ROMAN EDUCATION Mark Joyal, J.C. -

Central Anatolian Languages and Language Communities in the Colony Period : a Luwian-Hattian Symbiosis and the Independent Hittites*

1333-08_Dercksen_07crc 05-06-2008 14:52 Pagina 137 CENTRAL ANATOLIAN LANGUAGES AND LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES IN THE COLONY PERIOD : A LUWIAN-HATTIAN SYMBIOSIS AND THE INDEPENDENT HITTITES* Petra M. Goedegebuure (Chicago) 1. Introduction and preliminary remarks This paper is the result of the seemingly innocent question “Would you like to say something on the languages and peoples of Anatolia during the Old Assyrian Period”. Seemingly innocent, because to gain some insight on the early second millennium Central Anatolian population groups and their languages, we ideally would need to discuss the relationship of language with the complex notion of ethnicity.1 Ethnicity is a subjective construction which can only be detected with certainty if the ethnic group has left information behind on their sense of group identity, or if there is some kind of ascription by others. With only the Assyrian merchant documents at hand with their near complete lack of references to the indigenous peoples or ethnic groups and languages of Anatolia, the question of whom the Assyrians encountered is difficult to answer. The correlation between language and ethnicity, though important, is not necessarily a strong one: different ethnic groups may share the same language, or a single ethnic group may be multilingual. Even if we have information on the languages spoken in a certain area, we clearly run into serious difficulties if we try to reconstruct ethnicity solely based on language, the more so in proto-historical times such as the early second millennium BCE in Anatolia. To avoid these difficulties I will only refer to population groups as language communities, without any initial claims about the ethnicity of these communities. -

Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of the Sumerian Language

Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of the Sumerian Language Emilie´ Page-Perron´ †, Maria Sukhareva‡, Ilya Khait¶, Christian Chiarcos‡, † University of Toronto [email protected] ‡ University of Frankfurt [email protected] [email protected] ¶ University of Leipzig [email protected] Abstract cuses on the application of NLP methods to Sume- rian, a Mesopotamian language spoken in the This paper presents a newly funded in- 3rd millennium B.C. Assyriology, the study of ternational project for machine transla- ancient Mesopotamia, has benefited from early tion and automated analysis of ancient developments in NLP in the form of projects cuneiform1 languages where NLP special- which digitally compile large amounts of tran- ists and Assyriologists collaborate to cre- scriptions and metadata, using basic rule- and ate an information retrieval system for dictionary-based methodologies.4 However, the Sumerian.2 orthographic, morphological and syntactic com- This research is conceived in response to plexities of the Mesopotamian cuneiform lan- the need to translate large numbers of ad- guages have hindered further development of au- ministrative texts that are only available in tomated treatment of the texts. Additionally, dig- transcription, in order to make them acces- ital projects do not necessarily use the same stan- sible to a wider audience. The method- dards and encoding schemes across the board, and ology includes creation of a specialized this, coupled with closed or partial access to some NLP pipeline and also the use of linguis- projects’ data, limits larger scale investigation of tic linked open data to increase access to machine-assisted text processing. -

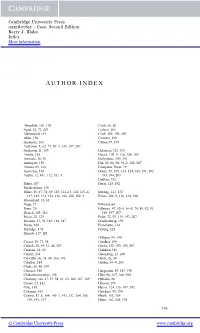

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. Blake Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Abondolo, 101, 105 Cook, 66, 80 Agud, 32, 72, 207 Corbett, 104 Aikhenvald, 191 Croft, 192, 193, 207 Allen, 150 Crowley, 100 Andersen, 163 Cutler, 99, 190 Anderson, J., 62, 71, 80–3, 135, 197, 207 Anderson, S., 109 Delancey, 123, 192 Anttila, 165 Dench, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Aristotle, 18, 30 Derbyshire, 100, 191 Armagost, 156 Dik, 62, 66, 68, 91–2, 188, 207 Artawa, 89, 124 Dionysius Thrax, 19 Austerlitz, 165 Dixon, 56, 105, 114, 124, 185, 191, 192, Austin, 12, 101, 112, 182–3 193, 194, 207 DuBois, 192 Baker, 187 Durie, 124, 192 Balakrishnan, 158 Blake, 15, 67, 78, 89, 107, 114–15, 124, 127–8, Ebeling, 121, 152 137, 143, 151, 154, 158, 186, 188, 192–3 Evans, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Bloomfield, 13, 63 Bopp, 37 Filliozat, 64 Bowe, 26 Fillmore, 47, 62–3, 66–8, 74, 80, 82, 91, Branch, 105, 116 188, 197, 207 Breen, 28, 125 Foley, 72, 92, 110, 192, 207 Bresnan, 47, 92, 185, 186, 187 Frachtenberg, 190 Bryan, 102 Franchetto, 124 Burridge, 174 Friberg, 123 Burrow, 117, 181 Gilligan, 99, 190 Caesar, 19, 73, 98 Giridhar, 100 Calboli, 18, 19, 31, 48, 207 Giv´on, 112, 192, 193, 207 Cardona, 64, 65 Goddard, 186 Carroll, 138 Greenberg, 15, 160 Carvalho, de, 31, 40, 186, 192 Groot, de, 30 Catullus, 184 Gruber, 67–9, 205 Chafe, 66, 80, 207 Chaucer, 148 Haegeman, 59, 187, 190 Chidambaranathan, 158 Hale, 96, 107, 168, 194 Chomsky, xiii, 47, 57, 58, 61, 62, 186, 187, 189 Halliday, 66 Cicero, 23, 112 Hansen, 193 Cole, 110 Harris, 124, 126, 147, 192 Coleman, 105 Hawkins, 99, 190 Comrie, 87–8, 104, 140–1, 142, 152, 154, 185, Heath, 155, 159 190, 191, 207 Heine, 162, 165, 193 219 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. -

The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars Number 2

oi.uchicago.edu i THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS NUMBER 2 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii MARGINS OF WRITING, ORIGINS OF CULTURES edited by SETH L. SANDERS with contributions by Seth L. Sanders, John Kelly, Gonzalo Rubio, Jacco Dieleman, Jerrold Cooper, Christopher Woods, Annick Payne, William Schniedewind, Michael Silverstein, Piotr Michalowski, Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Theo van den Hout, Paul Zimansky, Sheldon Pollock, and Peter Machinist THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS • NUMBER 2 CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2005938897 ISBN: 1-885923-39-2 ©2006 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2006. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago Co-managing Editors Thomas A. Holland and Thomas G. Urban Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Katie L. Johnson is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Front Cover Illustration A teacher holding class in a village on the Island of Argo, Sudan. January 1907. Photograph by James Henry Breasted. Oriental Institute photograph P B924 Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Infor- mation Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. -

Morphology Building Syntax: Constructive Case in Australian Languages

Morphology Building Syntax Constructive Case in Australian Languages Rachel Nordlinger Stanford University Pro ceedings of the LFG Conference University of California San Diego Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King Editors CSLI Publications httpwwwcslistanfordedupublications LFG R Nordlinger Morphology Building Syntax Constructive Case in Australia Intro duction A dening characteristic of lfg is that morphological words can carry the same kinds of functional information as syntactic phrases words and phrases are alternative means of enco ding the same syntactic relations Kaplan and Bresnan Bresnan That morphology comp etes with syntax in this way Bresnan is seen most clearly in noncongurational languages where inectional morphology takes on much of the functional load of phrase structure in more congura tional languages like English determining grammatical functions and constituency relations lfg is thus wellsuited to the analysis of noncongurationality and has pioneered muchwork on non congurational languages b oth in Australia and elsewhere Mohanan Bresnan Simpson Kro eger T Mohanan Austin and Bresnan Nordlinger and Bresnan Andrews among many others In this pap er I will b e concerned with the function of case in the dep endentmarking non congurational languages of Australia These Australian languages haveunusually extensive case marking and case concord Intuitively as has b een suggested bymany researchers working with these languages eg Hale Simpson Nash Austin Evans a it is this case marking that enables their -

The Nature of Specific Language Impairment: Optionality and Principle Conflict

The Nature of Specific Language Impairment: Optionality and Principle Conflict Lee Davies Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London August 2001 ProQuest Number: U642667 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642667 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 *I see nobody on the road,* said Alice. 7only wish I had such eyes,* the King remarked in a fretful tone. * To he able to see Nobody! And at that distance too! Why it*s as much as I can do to see real people, by this light!,... ABSTRACT This thesis focuses upon two related goals. The first is the development of an explanatory account of Specific Language Impairment (SLI) that can effectively capture the variety and complexity of the children’s grammatical deficit. The second is to embed this account within a restrictive theoretical framework. Taking as a starting point the broad characterisation of the children’s deficit, developed by Heather van der Lely in her RDDR (Representational Deficit for Dependant Relations) research program, I refine and extend her position by proposing a number of principled generalisations upon which a theoretical explanation can be based. -

CHICAGO ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY (CAD) Martha T

oi.uchicago.edu CHICAGO ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY CHICAGO ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY (CAD) Martha T. Roth 2010–11 saw the publication of the final volume of the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary. The last detailed tasks occupied Manuscript Editor Linda McLarnan, Research Assistant Anna Hudson Steinhelper, and me for much of the year. Below is an edited version of the lecture I presented at the celebratory symposium for the completion of the project, held at the Oriental Institute on 6 June 2011. For more detailed histories, the reader is referred to I. J. Gelb’s “Introduction” to CAD A/1 (1964) and Erica Reiner’s An Adventure of Great Dimension (2002). The CAD was ambitiously begun in 1921 under the guidance of James Henry Breasted, whose vision for collaborative projects launched the Oriental Institute, the University of Chicago’s first research institute. Housed originally in the basement of Haskell Hall and under the direction of Daniel D. Luckenbill, the small staff of scholars and students began to produce the data set by typing editions onto 5 x 8 cards, duplicating with a hectograph, parsing, and filing. Luckenbill died unexpectedly in 1927 at the age of 46, and Edward Chiera was called to Chicago from the University of Pennsylvania to take over the project. The enlarged resident staff was augmented by some twenty international collaborators, and in 1930 the project moved into its current home in the new building, to a spacious room on the third floor that was specially reinforced to hold the weight of tons of file cabinets and books. Technological advances allowed the old hectograph to be replaced with a modern mimeograph machine for duplicating the cards. -

NUMERALS 1 0.1. GENERAL the Sumerian Language Had A

CHAPTER TEN NUMERALS 10.1. GENERAL The Sumerian language had a "sexagesimal" system in which numer ation proceeded in alternating steps of 10 and 6: 1-10, 10-60, 60- 600, 600-3600, 3600-36000, 36000-216000. With sixty as the "hun dred", Sumerian numeration had the enormous advantage of being able to divide by 3 or 6 without leaving a remainder. The sexa gesimal system has left its traces in our modern divisions of the hour or of the compass. It permeates the metrological systems of the Ancient Near East. Powell 1971; 1989. Since cardinal and ordinal numbers, including fractions, as well as notations of length, surface, volume, capacity, and weight are next to exclusively written with number signs, we are poorly informed on the pronunciation and the morpho-syntactical behaviour of numbers in Sumerian. To what degree were numbers subject to case inflection? If 600 was pronounced ges-u "sixty ten", i.e., "ten (times) sixty", what was the pronunciation of "sixty (plus) ten", i.e., 70? Was there a difference of stress or some other means of intonation, e.g., *[ges(d)u] versus [gd(d)u]? Syntactically, persons or things counted were followed, not pre ceded, by numerals so that the position of a numeral corresponds to that of an adjective. For-purely graphic-exceptions to this rule see 5.3.6, note. 10.2. CARDINAL NUMBERS The oldest pronunciation guide for the Sumerian cardinal numbers 2 to 10 is an exercise tablet from Ebla: TM 75.G. 2198: Edzard 1980; 2003b. 62 CHAPTER TEN Ebla later tradition 1.