Talking Neolithic: the Case for Hatto-Minoan and Its Relationship to Sumerian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Minoan Crete Perhaps the Most Sophisticated Bronze Age

History of Minoan Crete Perhaps the most sophisticated Bronze Age civilization of the Mediterranean world was that of the Minoans. The Minoan civilization developed on and ruled the island of Crete from about 3,600 -1,400 BC. The Minoans established a great trading empire centered on Crete, which is conveniently located midway between Egypt, Greece, Anatolia, and the Middle East. Background to the Minoans The Minoan language, written in the script known as Linear A, remains undeciphered, so there remains much that we do not know about the ancient Minoans. For example, we do not even know what they called themselves. The term “Minoan” is a modern name and comes from the legendary King Minos. According to Greek mythology, King Minos ruled the island of Crete. He supposedly kept a Minotaur in a maze on the island and sacrificed young Greeks to feed it until it was killed by the hero Theseus. There are various legends about a King of Crete named Minos, and the ancient Greeks decided that all of them could not refer to the same man; thus, they assumed that there were many kings named Minos who had ruled Crete. When the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans rediscovered the civilization, he renamed them the Minoans, because he believed they were related to these ancient rulers of the island from Greek myth. Still, the lack of written evidence can be somewhat compensated for through the use of archaeology. We can make up a bit for our lack of knowledge from texts with information gleaned from archaeology. The Minoan civilization was forgotten until it was rediscovered by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in the first decade of the twentieth century. -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

Some Preliminary Notes on the Topography of Kaskaean Land

12 CAES Vol. 4, № 3 (August 2018) Where can Kaskaean settlements be found? Some preliminary notes on the topography of Kaskaean land Alexander Akulov independent scholar; Saint Petersburg, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hittite sources about Kaska had no aims to describe Kaskaean land per se, but only described those Kaskaean terrains which were close to Hittite land, while most of Kaskaean lands were unknown for Hittites. Toponymy is the key for Kaskaean topography. Many Kaskaean toponyms were initially related to rivers, so it is perspective to look at names of rivers of Black Sea region. Kaska people were a branch of Hattians and a ‘bridge’ between Hattians and people speaking Northwest Caucasian languages. The most perspective location in Kaskaean region is Özlüce/Gelevara river. Word Gelevara contains component -vara that correlates with Hattic root ur(a/i) “well”, “spring” and with Common West Caucasian ʕarə “stream”, “torrent”. In Kaskaean region there are no other modern names of rivers containing -ura/-vara component: it seems that in the basin of Gelevara the density of Kaskaean population was relatively high and Kaskaean settlements potentially can be found there. Keywords: Kaska; topography of Kaska; Kaskaean toponymy; Gelevara river; Bronze Age Anatolia 1. Introduction into the problem Kaska people were people who lived in mountainous East Pontic Anatolia in the Bronze Age. Kaska people are mainly known from Hittite sources which describing Hittite – Kaska frontier1. The problem of precise borders of Kaska land still remains unsolved due to elusive nature of Kaskaean material culture remains (Yakar 2008: 817). However, it is possible to determine some landmarks as most probable and natural borders of Kaska land. -

Journal of Eurasian Studies

JOURNAL OF EURASIAN STUDIES _____________________________________________________________________________________ Journal of the Gábor Bálint de Szentkatolna Society Founded: 2009. Internet: www.federatio.org/joes.html _____________________________________________________________________________________ Volume I., Issue 4. / October — December 2009 ____________________ ISSN 1877-4199 October-December 2009 JOURNAL OF EURASIAN STUDIES Volume I., Issue 4. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Publisher Foundation 'Stichting MIKES INTERNATIONAL', established in The Hague, Holland. Account: Postbank rek.nr. 7528240 Registered: Stichtingenregister: S 41158447 Kamer van Koophandel en Fabrieken Den Haag Distribution The periodical can be downloaded from the following Internet-address: http://www.federatio.org/joes.html If you wish to subscribe to the email mailing list, you can do it by sending an email to the following address: [email protected] The publisher has no financial sources. It is supported by many in the form of voluntary work and gifts. We kindly appreciate your gifts. Address The Editors and the Publisher can be contacted at the following addresses: Email: [email protected] Postal address: P.O. Box 10249, 2501 HE, Den Haag, Holland Individual authors are responsible for facts included and views expressed in their articles. _____________________________________ ISSN 1877-4199 © Mikes International, 2001-2009, All Rights Reserved _____________________________________________________________________________________ -

Central Anatolian Languages and Language Communities in the Colony Period : a Luwian-Hattian Symbiosis and the Independent Hittites*

1333-08_Dercksen_07crc 05-06-2008 14:52 Pagina 137 CENTRAL ANATOLIAN LANGUAGES AND LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES IN THE COLONY PERIOD : A LUWIAN-HATTIAN SYMBIOSIS AND THE INDEPENDENT HITTITES* Petra M. Goedegebuure (Chicago) 1. Introduction and preliminary remarks This paper is the result of the seemingly innocent question “Would you like to say something on the languages and peoples of Anatolia during the Old Assyrian Period”. Seemingly innocent, because to gain some insight on the early second millennium Central Anatolian population groups and their languages, we ideally would need to discuss the relationship of language with the complex notion of ethnicity.1 Ethnicity is a subjective construction which can only be detected with certainty if the ethnic group has left information behind on their sense of group identity, or if there is some kind of ascription by others. With only the Assyrian merchant documents at hand with their near complete lack of references to the indigenous peoples or ethnic groups and languages of Anatolia, the question of whom the Assyrians encountered is difficult to answer. The correlation between language and ethnicity, though important, is not necessarily a strong one: different ethnic groups may share the same language, or a single ethnic group may be multilingual. Even if we have information on the languages spoken in a certain area, we clearly run into serious difficulties if we try to reconstruct ethnicity solely based on language, the more so in proto-historical times such as the early second millennium BCE in Anatolia. To avoid these difficulties I will only refer to population groups as language communities, without any initial claims about the ethnicity of these communities. -

Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of the Sumerian Language

Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of the Sumerian Language Emilie´ Page-Perron´ †, Maria Sukhareva‡, Ilya Khait¶, Christian Chiarcos‡, † University of Toronto [email protected] ‡ University of Frankfurt [email protected] [email protected] ¶ University of Leipzig [email protected] Abstract cuses on the application of NLP methods to Sume- rian, a Mesopotamian language spoken in the This paper presents a newly funded in- 3rd millennium B.C. Assyriology, the study of ternational project for machine transla- ancient Mesopotamia, has benefited from early tion and automated analysis of ancient developments in NLP in the form of projects cuneiform1 languages where NLP special- which digitally compile large amounts of tran- ists and Assyriologists collaborate to cre- scriptions and metadata, using basic rule- and ate an information retrieval system for dictionary-based methodologies.4 However, the Sumerian.2 orthographic, morphological and syntactic com- This research is conceived in response to plexities of the Mesopotamian cuneiform lan- the need to translate large numbers of ad- guages have hindered further development of au- ministrative texts that are only available in tomated treatment of the texts. Additionally, dig- transcription, in order to make them acces- ital projects do not necessarily use the same stan- sible to a wider audience. The method- dards and encoding schemes across the board, and ology includes creation of a specialized this, coupled with closed or partial access to some NLP pipeline and also the use of linguis- projects’ data, limits larger scale investigation of tic linked open data to increase access to machine-assisted text processing. -

150506-Woudhuizen Bw.Ps, Page 1-168 @ Normalize ( Microsoft

The Ethnicity of the Sea Peoples 1 2 THE ETHNICITY OF THE SEA PEOPLES DE ETNICITEIT VAN DE ZEEVOLKEN Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. S.W.J. Lamberts en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 28 april 2006 om 13.30 uur door Frederik Christiaan Woudhuizen geboren te Zutphen 3 Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof.dr. W.M.J. van Binsbergen Overige leden: Prof.dr. R.F. Docter Prof.dr. J. de Mul Prof.dr. J. de Roos 4 To my parents “Dieser Befund legt somit die Auffassung nahe, daß zumindest für den Kern der ‘Seevölker’-Bewegung des 14.-12. Jh. v. Chr. mit Krieger-Stammesgruppen von ausgeprägter ethnischer Identität – und nicht lediglich mit einem diffus fluktuierenden Piratentum – zu rechnen ist.” (Lehmann 1985: 58) 5 CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................9 Note on the Transcription, especially of Proper Names....................................................................................................11 List of Figures...................................................................................................................................................................12 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................................................13 -

The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars Number 2

oi.uchicago.edu i THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS NUMBER 2 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii MARGINS OF WRITING, ORIGINS OF CULTURES edited by SETH L. SANDERS with contributions by Seth L. Sanders, John Kelly, Gonzalo Rubio, Jacco Dieleman, Jerrold Cooper, Christopher Woods, Annick Payne, William Schniedewind, Michael Silverstein, Piotr Michalowski, Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Theo van den Hout, Paul Zimansky, Sheldon Pollock, and Peter Machinist THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE SEMINARS • NUMBER 2 CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2005938897 ISBN: 1-885923-39-2 ©2006 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2006. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago Co-managing Editors Thomas A. Holland and Thomas G. Urban Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Katie L. Johnson is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Front Cover Illustration A teacher holding class in a village on the Island of Argo, Sudan. January 1907. Photograph by James Henry Breasted. Oriental Institute photograph P B924 Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Infor- mation Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. -

The Evolution of Civilizations Singled out for National Awards by a National Committee Headed by George Gallup

The Evolution of Civilizations n this perceptive look at the factors behind the rise and fall of I civilizations, Professor Quigley seeks to establish the analytical tools necessary for understanding history. He examines the applica- tion of scientific method to the social sciences, then establishes his historical hypotheses. He poses a division of culture into six levels, from the more abstract to the more concrete—intellectual, religious, social, political, economic, and military—and he identifies seven stages of historical change for all civilizations: mixture, gestation, expansion, conflict, universal empire, decay, and invasion. Quigley tests these hypotheses by a detailed analysis of five major civilizations: the Mesopotamian, the Canaanite, the Minoan, the classical, and the Western. "He has reached sounder ground than has Arnold J. Toynbee" —Christian Science Monitor. "Studies of this nature, rare in American historiography, should be welcomed. Quigley's juxtaposition of facts in a novel order is often provocative, and his work yields a harvest of insights"—American Historical Review. "Extremely illuminating" —Kirkus Reviews. "This is an amazing book. Quigley avoids the lingo of expertise; indeed, the whole performance is sane, impres- sively analytical, and well balanced"—Library Journal. CARROLL QUIGLEY taught the history of civilization at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service, and was the author of Trag- edy and Hope: The World in Our Time. Contents Diagrams, Tables, and Maps .................................................... 11 Foreword, by Harry J. Hogan ................................................... 13 Preface to the First Edition ....................................................... 23 1. Scientific Method and the Social Sciences.......................... 31 2. Man and Culture.................................................................. 49 3. Groups, Societies, and Civilizations.................................... 67 4. Historical Analysis .............................................................. 85 5. -

Northwest Caucasian Languages and Hattic

Kafkasya Calışmaları - Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi / Journal of Caucasian Studies Kasım 2020 / November 2020, Yıl / Vol. 6, № 11 ISSN 2149–9527 E-ISSN 2149-9101 Northwest Caucasian Languages and Hattic Ayla Bozkurt Applebaum* Abstract The relationships among five Northwest Caucasian languages and Hattic were investigated. A list of 193 core vocabulary words was constructed and examined to find look-alike words. Data for Abhkaz, Abaza, Kabardian (East Circassian), Adyghe (West Circassian) and Ubykh drew on the work of Starostin, Chirikba and Kuipers. A sub-set list of 15 look-alike words for Hattic was constructed from Soysal (2003). These lists were formulated as character data for reconstructing the phylogenetic relationships of the languages. The phylogenetic relationships of these languages were investigated by a well-known method, Neighbor Joining, as implemented in PAUP* 4.0. Supporting and dissenting evidence from human genetic population studies and archeological evidence were discussed. This project has produced a provisional set of character data for the Northwest Caucasian languages and, to a limited extent, Hattic. Phylogenetic trees have been generated and displayed to show their general character and the types of differences obtained by alternate methods. This research is a basis for further inquiries into the development of the Caucasian languages. Moreover, it presents an example of the method for contrast queries application in studying the evolution of language families. Keywords: Northwest Caucasian Languages, Hattic, Historical Linguistics, Circassian, Adyghe, Kabardian * Ayla Bozkurt Applebaum, ORCID 0000-0003-4866-4407, E-mail: [email protected] (Received/Gönderim: 15.10.2020; Accepted/Kabul: 28.11.2020) 63 Ayla Bozkurt Applebaum Kuzeybatı Kafkas Dilleri ve Hattice Özet Bu araştırma beş Kuzeybatı Kafkas Dilleri ve Hatik arasındaki ilişkiyi incelemektedir. -

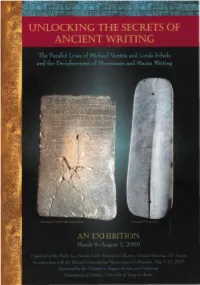

Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Writing

Figure 1: Left Cover Photograph Linear B tablet, Pylos Tn 316 Mycenaean, Late Helladic III B, 1200 B.C.E. Clay, accidental ly fired H 7.8 in. x W 5.0 in. x D 0.9 in. National Archaeological Museum, Athens Photograph © PASP slide archives OLM) On the front side of Pylos T n 3 16, the famous 'human sacrifice' tablet, the scribe experimented with the layout for entering information about ceremonial offerings made by the community of Pylos (pu-ro in large characters twice at left) to sanctuaries in the palatial territory of Bronze Age Messenia. Note the ideographic characters for golden vases and for human beings. Entries continue on the verso. It is debated whether the MAN and WOMAN entries j,,-, ,/ ; / were 'sacrificial victims' or 'sacristans' bringing the vases. The lower \11 part of the rectosurface has graffiti, possibly the Linear B abc's or y:L iroha, written by the scribe in testing the readiness of the clay. Cf. ~-- - ---.'.._ )/ /11:v T.G. Palaima, "Kn02-Tn 316," in S. Deger-Jalkoczy eta!. eds., FloreantStudia Mycenaea(Vienna 1999) Band II, 437-461. Figure 2: Drawing of the front of tablet PYTn 316. Line drawing by Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. Figure3: Right Cover Photograph Jade celt, the Leiden Plaque Maya, Early Classic period, C.E. 320 . Incised jade = H 8.5 in. x W 3.4 in. x D 0.4 in. Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, Holland Photograph © Justin Kerr, K2909 This incised jade, once used as a royal belt ornament , carries an inscription on the versothat tells of the accession (the "seating") of a Maya ruler which occurred on September 17, C.E. -

NUMERALS 1 0.1. GENERAL the Sumerian Language Had A

CHAPTER TEN NUMERALS 10.1. GENERAL The Sumerian language had a "sexagesimal" system in which numer ation proceeded in alternating steps of 10 and 6: 1-10, 10-60, 60- 600, 600-3600, 3600-36000, 36000-216000. With sixty as the "hun dred", Sumerian numeration had the enormous advantage of being able to divide by 3 or 6 without leaving a remainder. The sexa gesimal system has left its traces in our modern divisions of the hour or of the compass. It permeates the metrological systems of the Ancient Near East. Powell 1971; 1989. Since cardinal and ordinal numbers, including fractions, as well as notations of length, surface, volume, capacity, and weight are next to exclusively written with number signs, we are poorly informed on the pronunciation and the morpho-syntactical behaviour of numbers in Sumerian. To what degree were numbers subject to case inflection? If 600 was pronounced ges-u "sixty ten", i.e., "ten (times) sixty", what was the pronunciation of "sixty (plus) ten", i.e., 70? Was there a difference of stress or some other means of intonation, e.g., *[ges(d)u] versus [gd(d)u]? Syntactically, persons or things counted were followed, not pre ceded, by numerals so that the position of a numeral corresponds to that of an adjective. For-purely graphic-exceptions to this rule see 5.3.6, note. 10.2. CARDINAL NUMBERS The oldest pronunciation guide for the Sumerian cardinal numbers 2 to 10 is an exercise tablet from Ebla: TM 75.G. 2198: Edzard 1980; 2003b. 62 CHAPTER TEN Ebla later tradition 1.